Ships of the Sun Empress.

Posted: 2008-10-13 05:49pm

An introduction: Though nominally modern, this is still fantasy, just like the "new island" Tarrantry project I was involved in on the Warships1 board, and that recognition led me many years ago to an idea of my own--why not, and then I was infected by a 1990s MBA's ghost, take it to the next level?--that was initially largely unrelated: I'm not the sort of person who finds feminist utopia to be anything other than a pathetic collection of delusions by very delusional people, and I more or less had the idea that I'd create a feminist state and systematically work out all the ramifications of that in a realistic and plausible fashion, rather than to make a political statement.

First Postulate: You need to get rid of the men; it'll never work if they're around. Accepting reality for what it is, men simply end up in charge in primitive society for a myriad of reasons we don't need to go over here. So we need to get rid of the men. The easiest way to do this is with some kind of disease. This conveniently presented itself--M. wolbachia, a charming bacteria which can render males sterile and cause females to reproduce parthenogenically (yes, it actually exists, I jest thee not), which infects no less than 9% of neotropical insect species and a bunch of Protozoans--it's why you can treat Malarial fever with Doxycycline, as it kills M. wolbachia and then the protozoan causing Malaria can't reproduce. And even things as sophisticated as a shrimp. Okay, so we've got one requirement now. This leads to a problem--if you have a virulent plague, why didn't it just keep spreading?

Second Postulate: I need somewhere reasonably isolated from the rest of world history to put these people, or else you can forget the whole Tarrantry comparison, because the whole world will be infected. Oops. The solution was proposed by a kind friend of mine, Drake Irvine, who suggested that there was an easy location called Zealandia. 93% of Zealandia is submerged today; the other 7% is above the water and called New Zealand and New Caledonia. It's a continental fragment of Australia and has basically the same mineral geology as eastern Australia. Google it if you don't believe me. It's been underwater for 25 million years OTL, but it's at least continental landmass. That disturbingly makes this scenario more plausible than Tarrantry, despite a parthenogenically reproducing female society, because at least I'm using a continental landmass, so the massive a-historical changes only start 25 million years ago instead of 1 billion. Seriously. We'll just mess with Sahul (the continent of New Guinea--Australia) while we're at it...

Third Postulate: Dear God, if I want to avoid a bunch of colonial massacres, I have to make them as successful as Japan, or at least less stupid than China--either one works. That means we need a civilization there--can be multicultural, they'll have good reasons to stick together. Okay, so, we need Indonesians--Hindus, of course. Let's start settlement around 1000 in Sahul and move them east.. Muslim raiding and refugees in the 1300s/1400s will help. Toss in Chinese settlers brought by the treasure fleets of Zheng He, and the overrun populations of Lapita and their Maori overlords who were native to Zealandia, and we have something we can work with.

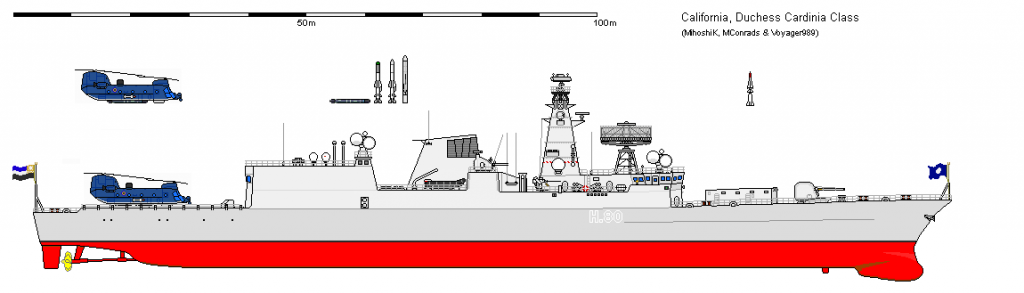

Enough background, I trust? Well, hardly; but enough background for the background. The first things I'm going to post in this thread are the period Encyclopaedia Britannica Eleventh Edition articles; then we'll go on to ships. For convenience, I'll place all the designs here. Presently, since I'm using a Mac, I haven't started cracking at them with SpringSharp (Anyone know of a free emulator?), so I've been limited to post-1945 missile ships and carriers, of which a fair number of them in their fleet have been fleshed out. They are a large country by that point--inadvertently, the whole rearranging continents mess dumped enough water on eastern Australia and gave them enough resources to make them quite rich, once I started studying both the geology and the ocean current changes. So it rather radically alters the post-WW2 naval landscape (the interwar period, less so, but still in an interesting fashion). So though I know they're not as popular, we'll start with the missile ships, and move out from that.

My original collaborate in this was Alexia but she and I hadn't talked for several years and she went and developed the whole idea in the opposite direction. So there's actually two Kaetjhastis, unrecognizably different from each other--and with extremely, extremely different fleets. Both, however, will be placed here, with her's under the alternate name East Amazonia, which is what the nation was frequently called before the late 19th century.

I'll get around to starting with the Kamunashjhad-class CBG of mid-1950s vintage (hulls laid down in 1942-43) sometime tomorrow/later today, so for the moment this post will just be followed by the fake EB1911 article segments for Kaetjhasti; we'll get into the meat of it tomorrow, and, as noted, to avoid clutter I'm keeping this all in one thread.

KÆTJHASTI, EMPIRE OF. A nation of Australia and Oceania, and one of the great powers of the world. The article is for convenience divided into ten sections: I. GEOGRAPHY; II. THE PEOPLE, III. LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE; IV. ART; V. ECONOMIC CONDITIONS; VI. GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION; VII. RELIGION; VIII. FOREIGN INTERCOURSE; IX. DOMESTIC HISTORY; X. SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS.

1. GEOGRAPHY. The Empire of Kætjhasti sits astride two continents, Australia and Zealandia, of which it possesses entirely the later, which is often, however, considered to be a section of Australia which was detached from the main part by a terrible cataclysm which caused sections of what is today the Coral Sea to subside so that it could be submerged. Though commonly thought as a point where Australia and Zealandia may have once been connected, the Strait of Samadare is a deep water extension of the Tasman Sea, and has likely always been submerged. The Empire also consists of the Tasman Islands to the south, consisting of the North and South Islands, and the Effingham and Forbisher islands which are next largest in size along with 26 lesser islands, which form an extension of the southern promontory of Australia; the Auckland or to the natives Trilajh islands which form an extension of southwestern Zealandia in the shape of rocky, mountainous islands extending to 59º52' South; the island of Tar'ek off the southeastern coast of Zealandia; the Kermadec Islands to the east, volcanic in nature and properly part of Polynesia; the New Hebrides to the north, predominantly the same; and the Solomons to the extreme north, volcanic extensions to the south of the rocky mass of Papua which terminates in the great islands of New Britain and New Ireland. In all, it may be said that the land Kætjhasti possesses completely engulfs the large and hot Coral Sea in the north, and through the narrow Strait of Samadare passes into the Tasman Sea, bounded on three sides by the Empire's landmass and partially to the third, opening only to the southwest and the inhospitable waters about Antarctica. This has naturally allowed for ease of commerce within the nation, and prevented easy access by foreign fleets in modern terms, considerably aiding the defensive task of the country.

The continent of Australia, divided into Australia Major and Australia Minor, the later commonly called the Great Peninsula or the Peninsula of Papua, after a Portuguese appellation for the wooly hair of the Negritoid natives who remain predominant in the interior and north shore, comprises the more populous and fruitful portion of the country, though it is generally less habitable to whites than Zealandia. Of the continent's territory, 1,050,000 square miles forming the western section of Australia Major is in the possession of the British Empire as West Australia Colony. The northern half of Australia Minor is divided between the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the west (80,000 square miles) and the German Empire in the east (83,000 square miles). The remainder of the territory is universally recognized as that of the Empire of Kætjhasti, some 2,087,000 square miles. Of this territory, at least one third is virtually uninhabitable desert, populated mainly by Negritoid primeval inhabitants who maintain a subsistence lifestyle without settlements and are regarded justly as inferior by the ruling Malay race of Kætjhasti, though these deserts have recently been pierced by several railroads which shall be considered later. The southern coast of the desert regions is hospital, though separated from the barren interior by a series of salt-pans. The Gulf St. Vincent provides a predominant feature here with the city of Sammjhi located upon it to the north of the Fleurieu Peninsula. The climate here is distinctly mediterranean, with wine being produced in some quantities, while extensive herds of sheep are driven in for the slaughter from the interior where marginal grazing land exists.

Further to the east, the Tasman Peninsula, or Caladar Country to the Kætjhasti, forms the main area of settlement for the dominate peoples of Kætjhasti in the south. This region has a warm and temperate climate along the coast and a cooler and pleasant climate inland, providing for extensive cultivation of grain. Significant quantities of coal and iron ore have also been obtained in the region, as well as the only significant quantities of opals known in the world to be mined. The great dividing range begins in these lower hills and continues north as the spine of the continent until it sinks to low hills along the Torresian Isthmus. The narrow band of coast to the south consists of dry forces of eucalyptus trees and has been populated by Kætjhasti's principle residents since the formation of the Empire. Further north the broad Kætjh plain, drenched in extensive warm rainfall from the currents of the Coral Sea that are compressed to the south through the Strait of Samadare, contains the immense bulk of the present Malay population and is entirely given over to the cultivation of rice, the jungle having been industriously cleared to effect the maximum production, and numerous lesser cities and industries situated near the Imperial Capitol of Kænahra. The great torrents of rain which make the Kætjh plain suitable for rice crops in its entirety, and riven with canals, are not entirely dissipated by the Great Dividing Range, and here in this area alone does significant quantities of rain penetrate beyond it into the interior, irrigating an area called the Italjhid plateau to the point where extensive grazing is possible.

The northern coast is provided in plentiful rainfall from both the Indian Monsoon in the west, and rain clouds passing over the lowland of the Torres Isthmus which the Great Dividing Range declines to, with average heights in some places only a hundred feet above sea level across the Isthmus. This guarantees an extensive range of the northern coast the same capability as the Kaetjh plain to support extensive cultivation of rice, and the landscape has been considerably reworked for even greater lengths of time than the Kaetjh plain, so that little of the original forests remain in places. However, overgrown, later forest developments over what were once rice paddies show that in previous times cultivation was still more extensive. A similar pattern extends to the southern coast of Australia Minor. The highlands of Australia Minor are heavily forested and filled with natural bounty, with the local negritoids having been progressively driven deeper into the high mountains which form the border. These mountains, forming the northern extent of Australian Kætjhasti, reach altitudes that despite being very near the equator afford them year-round snow in some places, and made both the advance of Kætjhasti to the north, or of the European powers to the south, entirely impracticable.

Of Zealandian Kætjhasti the immense distortion of the continent, or great island, may immediately be noted. Extending across 33º37' of latitude, extending from almost 7º above the Tropic of Cancer, or 17º South, to 54º South and with its further promontory islands extending into the furthest southern seas, the size of the landmass is a comparatively small 1,600,000 square miles, thought to be about twice the size of the island of Greenland, and purely continental in geologic makeup. The continent is shaped like a triangle arranged north northwest, with a bisecting spine approximately two-thirds of the way south down the landmass, known as the Zealandia Highlands, consisting of two immense plateaus with higher mountains of volcanic origin rising from them in turn, including the highest peak in Kætjhasti, the Mount Aoraki, reaching 16,916 feet above sea level. Much of the rest of the continent is very low-lying land, though sufficient variation in elevation provides for acceptable drainage, but makes for extensive networks of broad and slow running rivers ideal for canals. This terrain makes malarial fever and breakbone fever constant threats for the population, and extensive efforts to engage in the drainage of the land have been required by the government to facilitate further habitation.

Though the central plains have found themselves to some degree inhospitable due to the poor drainage, four regions beyond the highlands offer themselves to ease of habitation. The first of these is the western part of South Zealandia, comprising fourty percent of the land area of South Zealandia State. This area is rendered incredibly bountiful by the cool rainfall delivered continuously by the great easterlies which sweep around the Antarctic continent, and deliver rainfall in excess of 140 inches per year along the coasts, and considerable amounts in areas of the interior. But due to the height of the land, and the drainage afforded to the east by the Sambuhl swamps, the land lacks extensive swamps or marshes. Immense forests of coniferous trees of family Podocarpaceæ and broad-leaf evergreens cover this whole reach, and many of the lower-lying areas of the Zealandia Highlands as well. In this profusion of primeval bounty, an immense number of large bird species and unusual forms of mammals have prospered, as well as some of the rarest known reptilian species. Many have gone extinct due to the prodiguous spread of humanity; many remain. The Auckland islands to the southwest of this promontory show a trend from temperate rainforest to subarctic conditions over their full reach, and are a volcanic extension of the Zealandia Highlands chain.

To the immediate east, and before the Rehanoaka hills which split the centre of the southern continent, is the Sambuhl swamps. This immense concentration of swampland is twice the size of the Pripet Marshes of western Russia, and broadly comparable in diversity, being only very lightly habited. Beyond the Rehanoaka hills in turn is lowland near the coast which, being better facilitated in their drainage, and situated at a higher latitude with less rainfall, though still sufficient, affords an area of particular bounty, which has seen extensive colonization from the central parts of the Empire in recent years. To the northwest of this region is the very large Unohak Depression, which at one time was certainly an arm of the sea which was closed by volcanic activity and lays well below sea-level. It is now filled with a series of three major lakes, which will no doubt ultimately rise over æons to combine and form a new and great river to the sea, as no present means of drainage exists.

Now traversing the Zealandia highlands the Kra'taoi plateau affords itself an excellent position, being similarly afforded with quantities of immense rainfall, though not as great as the extreme southwestern reaches, with averages recorded in the range of 70 - 90 inches per year at the most, as the Tasman Islands serve as a barricade to these atmospheric concentrations. This area has long been the habitation of the Maori people who conquered the less sophisticated natives, though in this case the area has been given over entirely to the Maori variants of the Australis subspecies. Their tendency to adopt more to the farming of grains, introduced in quantity by the Chinese in the 1300s AD, has considerably changed the landscape and seen the felling of much of the once dense forests which covered this area. Directly below it, and comprising the rest of the central part of the continent, is another vast swamp, at least the size of the Sambuhl swamps and estimated to be somewhat larger, pinned between higher land and draining slowly to the east through broad coastal plains. Aggressive draining of this area has been commenced, in comparison to the pristine nature of the Sambuhl swamps. Though all directly connected, it bears no particular name, the Kætjhasti peoples having various appellations for different regions. The presence of this swamps and their easterly drainage means that the populations of central Zealandia are concentrated on the Kra'taoi plateau and the western coast.

The rest of the continent to the north is divided into two enormous peninsulas, the Tingfu'eh and the Enahouae. They are divided by an enormous bay formed by the subsidence of land in æons past, usually called the Orangetua Fjord, though the later term is incorrect, as it was not formed by glaciation. In both cases the land rises considerable, though there is more variation in the Tingfu'eh peninsula, which contains an extensive depression similar to the Unohak, though largely and only narrowly closed off from the sea, named the Willem Endracht, after the Dutchman whose exploration of the Orangetua afforded him the first sight of the depression. A myriad of thirty-one small lakes exist on its bottom, with high hills most prominent to the north and west. The Government has lately proposed studies into the feasibility of constructing a canal into depression, creating an artificial waterfall of a vast scale which would enable the generation of electric power, but these seems far beyond the present engineering capabilities of the Empire. The Enahouae peninsula affords a more generally high and less broken visage, rising in the far north to a plateau some 4,600 feet above sea level which contains on it Mount Paniae, reaching an elevation in turn of 9,972 feet. In this area the diversity of reptiles and birds is at its most extreme, and at least one species of giant birds persist in the highalnds. There is a sharp and strong divide between the western side, which is rain-shadowed by the high plateaus, and the eastern side, which is rainforest of a tropical nature, though with distinctive flora. In comparison, the Tingfu'eh peninsula has predominantly similar conditions to the Kætjh plains in the lowland, and the Great Dividing Range of Australia Major in the highlands, presumably from species having crossed over the narrow straits over time and establishing themselves strongly in the area, but also due to the Chinese and Malay colonists introducing all characteristics for the intensive cultivation of rice over many centuries.

The eastern territories of Kætjhasti, annexed as late as the early 1890s in the case of the New Hebrides and southern Solomons, are in those cases of volcanic origin and have a tropical or sub-tropical climate, though the only examples of the later are in the New Hebrides. Major eruptions have taken place, and the archipelagos are known to be extremely hostile in climate to whites, though the Malay populace of Kætjhasti has proved hardy in their efforts to administer and conquer the resisting tribes of the area despite the natural opposition provided by the usual jungle fevers. Further to the south are the Kermadec Islands, forming to the northeast a volcanic extension of the Zealandia Highlands as the Auckland Islands are a volcanic extension to the southwest. These islands are considerable in number and size among all those of Polynesia, but vary considerably in climate over their rugged and folding surfaces. Many of the southern islands have been populated by species from Zealandia, though the northerly islands have a predominance of the palm, and the introduction of the Polynesian pig is universal.

2. THE PEOPLE. The people, or peoples, of the Kætjhasti nation, provide an immense cross-section of the Malay and Pacific races beyond their more peculiar traits. Of the population as a whole, a plurality is of the Malay race in origin, numbering approximately fourty-five percent, and they are the dominant among the peoples to be discussed in their influence on culture and in the government of the state. More importantly, however, is the due consideration attended to the nature of the Kætjhasti. They have been previously argued to exist as the sole living subspecies of homo sapiens; recent evidence has however confirmed that they exist as a part of the human species, but one in a fundamental and irrevocable symbiotic relationship with the Kingdom Bacteria.

One of the most fundamental and immediately noticeable results of this symbiosis is that the primary races of Kætjhasti (irrespective of those on the fringes of the Empire who did not suffer infection) are entirely female. This peculiar social order was the result of the symbiosis in the form of a very well documented plague of the 1480s - 1490s AD, apparently introduced from the Tasman Islands by sailors, and attributed in the local Hindoo superstition to the wrath of Kali for the men having eaten meat. As the fantasy goes, a priestess offered herself up through immolation to Kali, and her wrath was relented, with the females of the sinful lands being allowed to survive through self-reproduction (See PARTHENOGENESIS). In general this has completely reordered all infected cultures, and created unique bonds over and above those of typical national identity which have allowed the Kætjhasti to form as a strong and unitary state body.

This relationship has only been very recently discovered. In 1908 in the southern city of Sahmunapura there was a case, discovered only a year hence after an investigation by local European-trained doctors into a strange malady affecting the women of the area, of workers at a local dye plant that had been recently established having been made sterile by contact with Sulfonamide dye compounds (See SULFONAMIDES, Medical Applications). This discovery at once provided the world with indications of the potential use of Sulfonamides in the treatment of infection, and provided a clear and cognizant theory of the development of the Kætjhasti which laid to rest prior proposals of a Homo Sapiens Australis, long argued against due to the extensive racial mix present in the Empire, but remaining the foremost proposal, heavily championed by supporters of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck's Theory of Evolution, as to the existence of the Kætjhasti. In the same way, then, that the return of sailors from the Americas brought with the scourge of syphilis, so was Kætjhastian society permanently reordered.

In biological results, the foremost is that pregnancy becomes a random act, rather than one associated with the act of copulation. This yields a tremendous pressure on the society, in which the inferior woman must already absorb all the tasks of the man, to deal with and mitigate the costs resulting from an essentially random disabling of all individuals in the society at some stages of their lives. Kætjhasti women have adapted, and proved hardy, to the necessity of working until the third trimester of pregnancy, and children are never raised individually, but by the communal blood family, called a term in the Kaetjh Javanese which best translates as 'Motherline'. Inheritance is direct from eldest to eldest along the Motherline, with an absolute social commandment toward the eldest providing for her sisters, with each generation usually numbering only two to three daughters on account of the immense number of miscarriages and spontaneous abortions that result from the imperfect method of Kætjhasti reproduction.

Firstly among the prominent results is the incredible arrangement of the family structure. Though approximating the great homes of the Sumatran family, encompassing many generations, the crucial component of Kætjhasti home life is that the family is all related by blood, and permanently so. As each woman is the descendent of one ultimate infected individual, these continuously spawning lines of clones form the only family possible to the Kætjhasti, and are their fundamental social organization. Though a mockery of marriage exists in the sanctifying of relations between women as an ostentatious display of their Sapphist affection, it has no bearing on the actual composition of the family. Rarely do such 'married' couples even regularly cohabit, with children inevitably remaining attached to their extended family throughout life, regardless of their accomplishments. That Sapphist attractions have become the norm is not considered surprising in a country where only twelve percent of the population is male; they have certainly contributed to the deplorable state of Kætjhasti morality when supplemented by the lax doctrines of the Kalist Hindoo and the fanatical devotions of the Tantra. This erotic love for the same sex is predominant in all portions of society from the Empress to the lowliest peasant woman, and is the subject of a great deal of high Kaetjhasti literature.

Frequently in youth this Sapphist attraction takes the forms of casual relationships between those of similar social status, caste, and occupation, not dissimilar to the institution of the Spartan Mess. These barbaric customs serve as the fundamental basis of all future interactions between individuals in Kætjhasti society, lending them immense social cohesion even at the same time that their government is oft-crippled by an extreme sort of sororal nepotism. At the same time, as a force for discipline in their military in the very same fashion as the Spartan Mess, it has giving them unit cohesion which provided a sound basis for the establishment of European discipline in their armies and a fierce loyalty to their comrades which makes the average Kætjhasti woman, however individually weak and incapable in combat, ferociously committed to standing her ground to the point of overwhelming even the hotheaded characteristics of many of the races which compose the Kætjhasti. It is this trait which earned them the respect of the Dutch in the War of 1890 over southwestern Papua, where the Dutch officers found the Kætjhasti soldiers willing to die in their places 'like stones', refusing to retreat no matter how many were killed and returning fire to the best of their ability, such that the Dutch were not once able to overcome a Kætjhastian defensive position held by their regular army instead of local militias.

In cases of labour, the Kætjhasti female proves herself dogged in all efforts to match western productivity. The chewing of the coca leaf and consumption of caffeine from coffee (brewed in the usual Asian fashion) and tea (of the Chinese variety) serve to aide the Kætjhasti where unassisted strength alone would not provide. The natural tendency of women toward hard and unstinting labour as part of their family duties has been expanded into the realm of the farm and industry with longer hours, more workers, and more than a bit of canny Malay ingenuity having proved sufficient to build their society on industrial and western lines. A love for education and a preference for a respect for hard work more similar to that of the Japanese than the absolute slothfulness of their original races has allowed the state to modernize with surprisingly little difficulty.

One finds the Kætjhasti in all their breeds to be a particularly emotional people. They laugh and cry openly, in all castes of society. Their personal emotions are readily talked about in the fashion of women, and they openly admit their weaknesses. Universally, such conversation is attended by physical closeness, and embracing and kissing in the fashion of Russians and much more intensely beside is completely normal for them, conveying no implication of Sapphist indulgence, though it may soon be given, with such affections indicated most uniquely by the brazen licking of the object of one's desire. No personal space exists among the Kætjhasti, and bathing and toilets lack entirely in privacy, with certain circumstances attending to sustained embraces between even those who were before absolute strangers.

With foreigners they retain a particularly cheerful demeanour, their highest respect being reserved for Germans and Austrians, for they associate with the German language all high culture, and admire in full the accomplishments of the German Empire. In no way do the Kætjhasti fail in their unstinting admiration for the German race, and extensive developments by major companies such as Krupp and IG Farben have taken place at the eager behest of the Kætjhasti government, while the consumption of German lager and schnapps is now a universal affection. The Kætjhasti, being incapable by their racial descent of fully appreciated the totality of German culture, have nevertheless proved quite able to assimilate all the most practical benefits as well as the traits they find at a facile emotional level to be the most endearing. For all Caucasians traveling through the country, however, universal warmth may be assured, and the Kætjhasti are exquisitely and unfailingly polite. They, viewing themselves as orthodox Hindoos, also retain particular favour for visiting coreligionists, and a guest will not lack in comfort, nor the provision of the immensely popular East Indian 'kretek' cigarette, though other forms of tobacco are usually lacking from their consumption.

Kætjhasti society, being a derivative of the ancient Hindoos of the Malay archipelago in the respects of its dominant race, is fundamentally polytheistic and superstitious. The nature of their society and their relations amongst themselves has rendered the spread of Christianity impossible, and the character of the Empress as a living goddess has not been touched by the reformers of the 1889 military coup who introduced a western style constitution, in this respect similar to Japan. The killing of beef cattle is universally prohibited, though consumption of lamb, seafood, and pork are unrestrained as well as fowl, save amongst those who for reasons of Hindoo religious practice abstain entirely from meat. On account of the innumerable raids conducted against them by the Muslim conquerors of the East Indies, from whom their ancestors formed refugees in more distant times, they hold an especial hatred for those who profess the faith of Mahomet. Both the Mahayana and Theravada strains of Buddhism, from Chinese and Malay sources respectively, combine with the Chinese introduction of certain Taoist elements to create a variant branch of Hindoos who by their exception syncretism have succeeded in largely integrating the heathens of the state.

Another component of the nature of the state is the caste system. As in the inhabitants of the Hindoo island of Bali, there are only four castes, the Dalits or Untouchables have been sensibly and mercifully eliminated from the Malay system, and their occupations integrated into the society as a whole. The castes are therefore only four in number, firstly the ubiquitous Brahmin or priestesses, who are ranked virtually equally with the second caste of Kshatriya or warriors, from whom come the majority of the nobility. Though both castes are almost universally Malay in race, they have comfortably integrated the chieftanesses and priestesses of the other infected peoples into their ranks, the caste system overall being much more fluid than in India, viz. the successful dominance of the Chinese colonists in comprising the greater part of the Vaishya caste of merchants. All farmers and workers not consisting of impoverished families (who nonetheless always freehold even in such cases) of the other castes are considered the Shudra or peasant caste.

The racial breakdown of Kætjhasti reflects the nation's diversity and divergence in no less fundamental ways, but these are secondary to the sexual considerations. In demographic terms, the infected population has an average total fertility rate of only 2.3, with the highest being that of the ethnic Chinese at 2.5, and most of the rest at 2.2. This tiny figure per woman belies the nature of Kætjhasti reproduction, where all individuals reproduce at this rate: A more accurate figure is therefore a respectable total fertility rate of 4.6. The uninfected population conversely has a more normal total fertility rate for primitive peoples of about 6.2. The ratio of infected to uninfected is only approximately 4:1, yielding 40 million infected Kætjhasti and 10 million uninfected. In this fashion the fundamental weakness of parthenogenic reproduction is shown due to the greater fecundity of the uninfected to the point of wiping out even the gains the Kætjhasti may have from their whole population being female. This is however not the only likely factor; it is certainly true that the Chinese, forming an extensive part of the merchant caste and thereby seeing little great physical exertion, have the highest birthrate, and certainly some improvement could be obtained.

Of the races, about 40% of the overall population, or 20 millions, are infected ethnic Malays who first settled the area of the Torres Isthmus and the Kaetjh plain, along with the northwestern coast of Australia Major and southwestern coast of Australia Minor, in the 1100s and established themselves as an eastward extension of the rice permaculture of the Indies, easily displacing the primitive and inferior Negritoid inhabitants. Some remnants in the far west and scattered through the great bulk of the Kætjhasti cultural areas remain uninfected to the number of perhaps 2 millions, for 22 millions in all being of Malay heritage. Though it at first may seem remarkable that the Malay race has succeeded, particularly considering the limited capability they show elsewhere in less trying circumstances than those the Kætjhasti state faces with its lack of men, on a more careful consideration it must be noted that the Malay is first oppressed by Islam in his normal circumstances, while the Hindoo faith does not provide such an impediment to modernization, nor such an inducement to fanaticism. Secondly, the Malay is certainly to be accounted intelligent among the races of the world, his principle fault being a base cunning which overwhelms all moral sense.

However, what is certainly to be accounted the most important point is that the upper classes, the high Brahmin and Kshatriya, are for the most part not pureblood Malays, but hold in them an admixture of Aryan blood. The intrepid Aryan conquerors of India, having subdued the Dravidian races of the south, journeyed further afield in the introduction of the Hindoo belief system to the East Indies. There, they unquestionably established themselves as the rulers and priests, and the successive waves of invasion from the Khmer, a debased Aryan race of Indochina, further served to strengthen the effect. It has been conclusively proved through analysis of the skulls of upper-caste Kætjhasti women that they are in the better part heavily Aryan, and tend to be an inch to two inches taller than the average population. Though debased, this connection with superiour faculties means that the traditional leadership of Kætjhasti, descendants of those upper-caste Hindoos who inevitably formed the break bulk of the flight from the Muslim conquest of the Malay archipelago, has long had the intelligence and capacity to guide the state and aid in modern industrialization, and enough of a semblence of martial commitment, aided by their ubiquitous barrack-room culture, to prove capable leading their troops in battle against even European armies.

Second of the races in Kætjhasti are the Maori. Comprising 6 millions of the infected population, they are the descendants of Polynesian conquerors of the native Lapita people of Zealandia. Falling easily upon the Lapita and defeating them, they adopted iron through trade with the Malays of Sahul and maintained to the present a warlike culture even when all the males in their society had been lost, defending the high mountains of the central plateau from the uninfected Maori to the south and causing much trouble for the government, with the first Empress, Yashovati I, said to have been sufficiently impressed as to take a chieftaness as a lover from among their number in a rare expression of her perversion for the otherwise upright and brilliant founding monarch of the Imperial line. Being taller and physically stronger than the weak Malay women who nonetheless dominate the state, they are considered among the best of the infantry that Kætjhasti can field, though only when led by Malay officers with the highest admixture of Aryan blood, their proving too hot-headed and given to emotional frenzy and panic to properly govern themselves in war or peace, but a valid contribution to the state under the guidance of their conquerors.

The uninfected Maori of the southlands of Zealandia and the Kermadec Islands provide the largest uninfected group, and the most open to Christianity, with not less than a fourth of their number having been converted since the Imperial government was compelled to open its borders. The Maori man is naturally honest and honourable, and has proved willing to fight for his alien sovereign with surprising aplomb and typical ferocity, and they are prized as great seafarers and whalers. Combined, the southlands Maori and Kermadec islanders comprise 4 millions of the population, and one which has maintained substantial independence from the tendency toward unity in the Kætjhasti state, almost entirely due to the continued guiding influence of men in their society. Several lesser Polynesian cultures exist in Kætjhasti, but are insufficiently documented to be included.

Chinese comprise the third largest population. Settling in the northwest of Zealandia in the 1380s through 1450s and growing constantly right up until the moment of the plagues, they were introduced by the great Chinese eunuch-Admiral Zheng He at the behest of the Ming Dynasty, who developed extensive ties with the Kætjhasti and provided for them to knowledge to build the immense Star Rafts which fatefully brought to them the plagues of the Tasman Islands. They thoroughly dominate the merchant classes and are universally wealthy, causing no small amount of resentment, though their working relationship with and loyalty to the Imperial government is absolute, and their cultures have largely integrated, to the point where most identify themselves as Hindoo, though the Buddhist and Taoist influences remain predominant; the teachings of Confucius have proved sufficiently unable to cope with the situation of the Kætjhasti as to see them generally discarded.

The Chinese inhabitants of Kætjhasti are universally infected, and their racial descent is of the lowest form of Chinese, being predominantly Cantonese and Min speakers from the south of China who never benefited from the infusions of noble Manchu blood. They comprise not less than 4 millions of the Imperial population, and though only one-tenth of the infected population, dominate the upper echelons of commerce thoroughly and are greatly prominent as industrialists and scientific professionals, also being very visible in the universities and in the Kætjhastian branches of many German corporations that have been established in the past two decades. In this fashion, the Chinese have access to the halls of power, primarily on fiscal matters, and have produced many ministers for the otherwise largely Kshatriya government, with their innate capacity for fiscal matters well compared to that of Jewry.

Of the next largest infected race, the Lapita, it may be said that their culture has been obscured in all areas except the northeast peninsula, which remained a stronghold until captured by the campaigns of Sridarnya I and integrated into the Empire. The infected population of Lapita consists of 4 millions, primarily concentrated in the northeast and otherwise spread through the areas of Maori population. They do, however, have uninfected counterparts to the number of about 3 millions in the southlands, where the Lapita and Maori, other than in the northeast, remained the most separate. The antagonism between the Lapita farmers and the Maori conquest class here has considerably aided in Imperial control of the southlands and the tightened grip of the state on its uninfected minorities.

The remaining infected population is divided between about 4.5 millions of those of mixed race ancestry, predominantly Maori-Lapita or Malay-Chinese, though also some Maori-Chinese and Maori-Malays, who are spread throughout all levels of society and well integrated with the Imperial state, largely adopting the culture of the region that they inhabit, and a series of minor cultures on the other hand. These minor cultures include in their numbers about 250,000 each infected Papuans and Australians, the two principle branches of the negritoid race in Australia and much marginalized in Kætjhasti society, and the 500,000 strong Zealandia Highlanders, the Chomo, whose martial ferocity has given them a reputation as the Amazons of the Empire, only matched by their absolute and fanatical devotion to the Empress as the Sun Goddess. Extremely primitive, they are nonetheless the most interesting race, being unknown in their primordial origins. Analysis of their skulls and consideration of their great height suggests their original ancestors, per the theory of M. Chistyakov of the St. Petersburg institute, were related to the Ainu and in ancient times were universally present on all the islands of the Pacific. Their language is however isolated, with no known related tongues. The last group, of several hundred thousands, are the Torres Islanders, who inhabit islands off the Torresian Isthmus in the Coral Sea and are believed to be of Melanesian ancestry.

A last infected population, and of special note, are the Thousand Families. More precisely comprising of two thousand families, they are commonly called the Thousand Families due that being the number of European origin. Consisting of the descendants of numerous shipwrecked unfortunate women and children, including the unfortunate survivors of several penal ships to West Australia which went off course in the late 18th century, but stretching all the way back to the famous Portuguese Fernandez family of the early 16th century, these families are entirely integrated into Kætjhasti society, infected with the parasite or symbiot through unknown means (their existence was one of the prime arguments against the theories of Lamarck), and sharing in the vices of their forcibly adopted culture. They are in all cases true to their Aryan blood and, adopted by Hindoo religious custom into Kshatriya families and caste, remain extremely prominent out of all proportion in the government and military. The other thousand families include those of Thai, Khmer, and Vietnamese heritage, as well as many Japanese and some Indians, along with at least one family of Arab origin; of these the Japanese and Indians are the most prominent, though those of Vietnamese ancestry are the largest group. They are less successful in general, however, than those of white ancestry, but equally revered as 'gifts from deities of the sea'.

A final note may conclude our consideration of the peoples of Kætjhasti. Over the course of the past seventy-five years, as trade became fully normalized and extensive with Kætjhasti, there has been a continuous number of European, and some women from European colonies or Japan and other Asian states with a capacity to trade with Kætjhasti, who have intentionally sought out the nation. These deranged women, usually with Sapphist tendencies, have tended to be less integrated into Kætjhasti society, but usually also more fanatical in their loyalty to the Empire, and frequently completely abandon their prior religion and wholeheartedly adopt the most perverse and lewd elements of Kætjhasti society. The Kætjhasti accept them, and their numbers are now thought to reside in the tens of thousands, with many of them infected by the same bacterial parasite as the main population. The government has cooperated in the banning of provision of visas for single women, but as a matter of policy has approved all requests for asylum by those who manage to find Kætjhasti shores illicitly, and so this strange form of immigration continues, albeit at a trickle.

3. LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE. The languages and literature of the Kætjhasti reflect their position as a multiracial Empire systematically. Until recently there was no formal standard on language, though Imperial Rescripts were posted in Kætjh Javanese, the native language of more than two fifths of the population, including all the governing Kshatriya classes (even those not racially Malay have generally adopted the tongue).

Kætjh Javanese began to diverge from Old Javanese in the 1000s during the height of usage of that language. The divergence however became extreme in the 13th century when the rise of the Majapahits in the western Malay Archipelago caused significant changes between the two languages. The later fall of the Majapahits in favour of the Islamic traders and conquerors who have completely changed the history of the archipelago left a permanent split between the two languages. The refugees from the fall of the Majapahits brought to Kætjhasti some of their linguistic innovations, but being of the highest Brahmin classes for the most part they were most interested in religious works. Already of Old Javanese, of the 25,500 known words of their vocabulary, 12,500 are borrowed from Sanskrit. This is certainly not the case in every-day speech, but heavily influenced the language and influenced Kætjh Javanese moreso.

With the basic genesis of the language established, the number of loan words from Sanskrit in the early Kætjh dialect was on the order of 13,000 and the use of Sanskrit as a religious language in Hindu devotion never completely ceased. The language diverged heavily from here, however, with the extensive addition of loan words from the local Negritoid peoples and Melanesians. The Lapita and Maori of Zealandia further added numerous words to the tongue, and the arrival of Chinese settlers in the late 14th century lent further to a polyglot tongue which due to these extensive loans already was likely unintelligible with Middle Javanese.

The great collapse of their society, and their descent into an entirely female people, completed for the Malays of Kætjhasti the evolution of their tongue into a distinct and different form of the Malay languages. It may be best described that if the present Javanese tongues are the Romance languages of western Europe, Kætjh Javanese is the Rumanian: Still clearly recognizable in its descent and yet substantially different in most respects and with extensive foreign influence.

With this background the language has subsequently been elevated not merely as the court tongue (though superceded in religious roles by Sanskrit) but as the common discourse for most government transactions and as a second language necessary in almost all arenas except commerce, where the dominance of the Chinese has guaranteed the Cantonese tongue parity with Kætjh Javanese.

The 4 January 'Bayonet Revolt' of 1889 brought the reformist National Union Party into power, and their interest in linguistics was marked. Since taking power over the government, in the interest of concepts of the fundamental Hindu identity of the State, they have launched a concerted effort to incorporate more concepts and words from the Sanskrit into the modern Kætjh Javanese tongue, while preserving the traditional abugida script on the Indian form which Old and Middle Javanese were also composed in, against competing proposed romanizations. The National Union Party also formalized the state languages, providing for publication of government documents in both Kætjh Javanese and German, while allowing each different lander or state under then new constitution to declare an official state language in which official documents and parliamentary debate may also occur.

The official state languages comprise the majority of other tongues spoken in the Empire's core territories. These are Cantonese, Maori, Lapita, and Chomayu. All correspond with an infected ethnic group and a state government (or several) and are the languages of the commoners in that region in general, though usually local notables will have learned it as children. In general the upper classes know Kætjh Javanese and at least one European language as well, however, and only Cantonese enjoys status as a full second Imperial language by the ubiquity of its use in commercial transactions. For a woman of refinement of Maori or Chomayu background, for instance, the knowledge of her native tongue as well as Kætjh Javanese, Cantonese, and French or German is virtually universal. Malays and Cantonese, however, frequently learn not merely but two foreign languages; the most common are German (after recent propagation efforts of the Kætjhasti-German League, it is now mandatory in schools), French, Dutch, and English. Portuguese and Spanish are also sometimes taught; other languages are uniformly absent from the curriculum of even majority universities, though plans exist to change this.

Competing Abugidas and Romanizations exist for Maori, Lapita, and Chomayu, with Cantonese still relying on the Chinese character system, though the Standard Romanization was recently adopted, as Cantonese has proved relatively conservative in the Kætjhasti usage. The government has not sought to regulate these languages.

Kætjh Javanese is spoken as the primary language in twelve lander of the Empire. Cantonese is spoken as the primary language in only three, Tingfu'eh, Wuna, and Zhujiang, but they are very densely populated. Maori is predominantly spoken in six states, though these are lightly populated.

Among the lesser tongues of the Empire, Teouma and Xaapeta States are the only states with a majority Lapita population; Chomo State is almost exclusively Chomoi in population and therefore speaks the Chomayu language to the rate of 90%. Aeroaki State, usually called South Zealandia State, has co-officiality of a variant Lapita dialect and Maori. Of the two incorporated territories, both narrowly speak Kætjh Javanese over the native Aboriginal dialects, being lightly settled, mostly by

railroad workers.

Uniquely among the tongues, Chomayu is a language isolate with no known relations, though it has been conjectured that the Chomo peoples are related to an antediluvian universal Pacific population related to the modern Ainu. This classification, and hypothesis, based on analysis of the similarities in the skulls of Chomo and Ainu, has naturally led to efforts to prove a relationship between the two languages, but as the Ainu tongue has been rapidly displaced by Japanese, the efforts have proved difficult due to the lack of an extensive Ainu vocabulary or knowledge of any ancestry for the language.

Tongues without formal representation exist in the Empire proper. Two minor Polynesian languages exist in the Zealandia Highlands with spoken populations of a few tens of thousands at the most, related to Maori but notably divergent. They are divided between infected and uninfected populations based on the village. The Min dialect of Chinese is very prominent as a local tongue in Tingfu'eh state to the point of competing with Cantonese, and the Hakka dialect is spoken by a small percentage of the population in Zhujiang state. The small Melanesian population on the Torres Isthmus maintains a distinct language. The Negritoid settled inhabitants of the Empire's territories on Australia Minor display countless languages, with many thought to be undiscovered and all spoken by very; the same is true of the aboriginal Negritoids of Australia Major.

Of the external territories, the entirety of the Kermadec Islands speak a profusion of Polynesian tongues, estimated as many as seventeen, their descents traced to the Rarotongan, Tongarevan, Rakahanga, and Pukapukan languages of the Cook Islands. The New Hebrides, however, feature a greater profusion of tongues; Kætjhasti ethnographers have documented more than a hundred of Melanesian origin and three of Polynesian origin. At least a further fourty languages exist in the South Solomon Islands, though few details are known about them despite extensive Kætjhasti efforts to seize control of the interior of the islands.

The literature of Kætjhasti is almost entirely produced in Kætjh Javanese or outright in old Sanskrit, which has seen a major revival at the hands of the National Union Party and recent concepts of a distinct and Hindu national identity. An epic poem, The Self-Immolation of the Brahmin Purani is the principle native religious work, compiled from oral sources in the 1840s by Samijha sri Wanava. It purports to explain the all-female nature of the Kætjhasti through the legend of the priestess of the great temple of Kali at Retangapura, by the name of Purani, who discovered that a plague had rendered the men who came to her over matters of fertility sterile. She launched on a dream-quest, a unique feature of Kætjh Hinduism related to the native Aboriginal beliefs, which led her to know that it was the punishment of the Gods for sailors having butchered cows in the southlands and eaten them.

Turning to her patron Goddess, the Brahmin begged that they should not be extinguished, that the women of the nation might survive out of their piousness to the Gods, in contrast to the sin of the men. She ascended to a holy place to the dread Goddess, and commanded the villagers to build a pyre for herself which she climbed and lit with a torch and pot of bitumen, kneeling in supplication to Kali as she burned. The goddess acknowledge the supreme sacrifice of her appeal, and took it upon herself to provide the Kætjhasti women with the means of reproducing themselves, while she exacted a particular further price from Purani herself, elevating her soul, given up by the Brahmin as her sacrifice to Kali, into a Rakshasas tasked with reaping horribly of the children of the women of the land, that they might survive, but never again enjoy bountiful fertility.

In general the old literature of the Kætjhasti is religious in this fashion, both to explain their unique situation, which they tended to recognize through contact with the outside world at a fairly early period, and to justify the masculine components of the Mahabharata and Ramayana and the other principle Hindu epics which comprise the bulk of their religious literature, and explain how the allusions and examples still have particular relevance for their society and the comportment of the Kshatriya and peasantry alike. Early works diverging noticeably from this scheme include the famous Commentaries of Yashovati the First, which she composed after being introduced to Caesar's Commentaries by her principle European advisor, Martin van Heerskomp. The writing is however poor in its imitation of Caesar; though the detail is excellent and language crisp by the standards of Kætjhasti composition, it is clear that the work is pseudo-religious in nature, and self-justifying toward the creation of the Imperial Cult, which makes it serve virtually as an additional religious text among the Kætjhasti but considerably lessens is value as an historic document to European world.

Of greater interest from the period, however, is the Travels of Princess Sridarnya, the Kætjhasti account of the Empress' younger sister's travels through Europe in the 1660s, including her famed audience with Louis XIV of France. The work presents a lively contrast to the stories of the European observers, and the princess, herself a trusted aide of her older sister, provided evaluations of the foreign rulers for the Empress to consider, which present a remarkable series of impressions of Europe's sovereigns from the alien perspective of the Kætjhasti in the era of the Sun King. The work is however risque in many respects; the inhibitions of the Kætjhasti writer are few.

Travelogues of this sort have vied with the recent development of novels, generally Romantic or Historical, in native Kætjhasti literature in imitation of Europe in the later part of the 19th century. Within the past twenty years, however, there has been a marked tendency to the composition of historical poems and epics based on existing peasant fables to create a distinct national corpus, much at the behest of the National Union Party. These sorts of tales have been supplemented by the thoroughly competent accounts of the Dutch War of 1890, usually from the officers who served, representing a European interest in the historiography of the battlefield and the lessons which might be learned from it.

First Postulate: You need to get rid of the men; it'll never work if they're around. Accepting reality for what it is, men simply end up in charge in primitive society for a myriad of reasons we don't need to go over here. So we need to get rid of the men. The easiest way to do this is with some kind of disease. This conveniently presented itself--M. wolbachia, a charming bacteria which can render males sterile and cause females to reproduce parthenogenically (yes, it actually exists, I jest thee not), which infects no less than 9% of neotropical insect species and a bunch of Protozoans--it's why you can treat Malarial fever with Doxycycline, as it kills M. wolbachia and then the protozoan causing Malaria can't reproduce. And even things as sophisticated as a shrimp. Okay, so we've got one requirement now. This leads to a problem--if you have a virulent plague, why didn't it just keep spreading?

Second Postulate: I need somewhere reasonably isolated from the rest of world history to put these people, or else you can forget the whole Tarrantry comparison, because the whole world will be infected. Oops. The solution was proposed by a kind friend of mine, Drake Irvine, who suggested that there was an easy location called Zealandia. 93% of Zealandia is submerged today; the other 7% is above the water and called New Zealand and New Caledonia. It's a continental fragment of Australia and has basically the same mineral geology as eastern Australia. Google it if you don't believe me. It's been underwater for 25 million years OTL, but it's at least continental landmass. That disturbingly makes this scenario more plausible than Tarrantry, despite a parthenogenically reproducing female society, because at least I'm using a continental landmass, so the massive a-historical changes only start 25 million years ago instead of 1 billion. Seriously. We'll just mess with Sahul (the continent of New Guinea--Australia) while we're at it...

Third Postulate: Dear God, if I want to avoid a bunch of colonial massacres, I have to make them as successful as Japan, or at least less stupid than China--either one works. That means we need a civilization there--can be multicultural, they'll have good reasons to stick together. Okay, so, we need Indonesians--Hindus, of course. Let's start settlement around 1000 in Sahul and move them east.. Muslim raiding and refugees in the 1300s/1400s will help. Toss in Chinese settlers brought by the treasure fleets of Zheng He, and the overrun populations of Lapita and their Maori overlords who were native to Zealandia, and we have something we can work with.

Enough background, I trust? Well, hardly; but enough background for the background. The first things I'm going to post in this thread are the period Encyclopaedia Britannica Eleventh Edition articles; then we'll go on to ships. For convenience, I'll place all the designs here. Presently, since I'm using a Mac, I haven't started cracking at them with SpringSharp (Anyone know of a free emulator?), so I've been limited to post-1945 missile ships and carriers, of which a fair number of them in their fleet have been fleshed out. They are a large country by that point--inadvertently, the whole rearranging continents mess dumped enough water on eastern Australia and gave them enough resources to make them quite rich, once I started studying both the geology and the ocean current changes. So it rather radically alters the post-WW2 naval landscape (the interwar period, less so, but still in an interesting fashion). So though I know they're not as popular, we'll start with the missile ships, and move out from that.

My original collaborate in this was Alexia but she and I hadn't talked for several years and she went and developed the whole idea in the opposite direction. So there's actually two Kaetjhastis, unrecognizably different from each other--and with extremely, extremely different fleets. Both, however, will be placed here, with her's under the alternate name East Amazonia, which is what the nation was frequently called before the late 19th century.

I'll get around to starting with the Kamunashjhad-class CBG of mid-1950s vintage (hulls laid down in 1942-43) sometime tomorrow/later today, so for the moment this post will just be followed by the fake EB1911 article segments for Kaetjhasti; we'll get into the meat of it tomorrow, and, as noted, to avoid clutter I'm keeping this all in one thread.

KÆTJHASTI, EMPIRE OF. A nation of Australia and Oceania, and one of the great powers of the world. The article is for convenience divided into ten sections: I. GEOGRAPHY; II. THE PEOPLE, III. LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE; IV. ART; V. ECONOMIC CONDITIONS; VI. GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION; VII. RELIGION; VIII. FOREIGN INTERCOURSE; IX. DOMESTIC HISTORY; X. SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS.

1. GEOGRAPHY. The Empire of Kætjhasti sits astride two continents, Australia and Zealandia, of which it possesses entirely the later, which is often, however, considered to be a section of Australia which was detached from the main part by a terrible cataclysm which caused sections of what is today the Coral Sea to subside so that it could be submerged. Though commonly thought as a point where Australia and Zealandia may have once been connected, the Strait of Samadare is a deep water extension of the Tasman Sea, and has likely always been submerged. The Empire also consists of the Tasman Islands to the south, consisting of the North and South Islands, and the Effingham and Forbisher islands which are next largest in size along with 26 lesser islands, which form an extension of the southern promontory of Australia; the Auckland or to the natives Trilajh islands which form an extension of southwestern Zealandia in the shape of rocky, mountainous islands extending to 59º52' South; the island of Tar'ek off the southeastern coast of Zealandia; the Kermadec Islands to the east, volcanic in nature and properly part of Polynesia; the New Hebrides to the north, predominantly the same; and the Solomons to the extreme north, volcanic extensions to the south of the rocky mass of Papua which terminates in the great islands of New Britain and New Ireland. In all, it may be said that the land Kætjhasti possesses completely engulfs the large and hot Coral Sea in the north, and through the narrow Strait of Samadare passes into the Tasman Sea, bounded on three sides by the Empire's landmass and partially to the third, opening only to the southwest and the inhospitable waters about Antarctica. This has naturally allowed for ease of commerce within the nation, and prevented easy access by foreign fleets in modern terms, considerably aiding the defensive task of the country.

The continent of Australia, divided into Australia Major and Australia Minor, the later commonly called the Great Peninsula or the Peninsula of Papua, after a Portuguese appellation for the wooly hair of the Negritoid natives who remain predominant in the interior and north shore, comprises the more populous and fruitful portion of the country, though it is generally less habitable to whites than Zealandia. Of the continent's territory, 1,050,000 square miles forming the western section of Australia Major is in the possession of the British Empire as West Australia Colony. The northern half of Australia Minor is divided between the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the west (80,000 square miles) and the German Empire in the east (83,000 square miles). The remainder of the territory is universally recognized as that of the Empire of Kætjhasti, some 2,087,000 square miles. Of this territory, at least one third is virtually uninhabitable desert, populated mainly by Negritoid primeval inhabitants who maintain a subsistence lifestyle without settlements and are regarded justly as inferior by the ruling Malay race of Kætjhasti, though these deserts have recently been pierced by several railroads which shall be considered later. The southern coast of the desert regions is hospital, though separated from the barren interior by a series of salt-pans. The Gulf St. Vincent provides a predominant feature here with the city of Sammjhi located upon it to the north of the Fleurieu Peninsula. The climate here is distinctly mediterranean, with wine being produced in some quantities, while extensive herds of sheep are driven in for the slaughter from the interior where marginal grazing land exists.

Further to the east, the Tasman Peninsula, or Caladar Country to the Kætjhasti, forms the main area of settlement for the dominate peoples of Kætjhasti in the south. This region has a warm and temperate climate along the coast and a cooler and pleasant climate inland, providing for extensive cultivation of grain. Significant quantities of coal and iron ore have also been obtained in the region, as well as the only significant quantities of opals known in the world to be mined. The great dividing range begins in these lower hills and continues north as the spine of the continent until it sinks to low hills along the Torresian Isthmus. The narrow band of coast to the south consists of dry forces of eucalyptus trees and has been populated by Kætjhasti's principle residents since the formation of the Empire. Further north the broad Kætjh plain, drenched in extensive warm rainfall from the currents of the Coral Sea that are compressed to the south through the Strait of Samadare, contains the immense bulk of the present Malay population and is entirely given over to the cultivation of rice, the jungle having been industriously cleared to effect the maximum production, and numerous lesser cities and industries situated near the Imperial Capitol of Kænahra. The great torrents of rain which make the Kætjh plain suitable for rice crops in its entirety, and riven with canals, are not entirely dissipated by the Great Dividing Range, and here in this area alone does significant quantities of rain penetrate beyond it into the interior, irrigating an area called the Italjhid plateau to the point where extensive grazing is possible.

The northern coast is provided in plentiful rainfall from both the Indian Monsoon in the west, and rain clouds passing over the lowland of the Torres Isthmus which the Great Dividing Range declines to, with average heights in some places only a hundred feet above sea level across the Isthmus. This guarantees an extensive range of the northern coast the same capability as the Kaetjh plain to support extensive cultivation of rice, and the landscape has been considerably reworked for even greater lengths of time than the Kaetjh plain, so that little of the original forests remain in places. However, overgrown, later forest developments over what were once rice paddies show that in previous times cultivation was still more extensive. A similar pattern extends to the southern coast of Australia Minor. The highlands of Australia Minor are heavily forested and filled with natural bounty, with the local negritoids having been progressively driven deeper into the high mountains which form the border. These mountains, forming the northern extent of Australian Kætjhasti, reach altitudes that despite being very near the equator afford them year-round snow in some places, and made both the advance of Kætjhasti to the north, or of the European powers to the south, entirely impracticable.

Of Zealandian Kætjhasti the immense distortion of the continent, or great island, may immediately be noted. Extending across 33º37' of latitude, extending from almost 7º above the Tropic of Cancer, or 17º South, to 54º South and with its further promontory islands extending into the furthest southern seas, the size of the landmass is a comparatively small 1,600,000 square miles, thought to be about twice the size of the island of Greenland, and purely continental in geologic makeup. The continent is shaped like a triangle arranged north northwest, with a bisecting spine approximately two-thirds of the way south down the landmass, known as the Zealandia Highlands, consisting of two immense plateaus with higher mountains of volcanic origin rising from them in turn, including the highest peak in Kætjhasti, the Mount Aoraki, reaching 16,916 feet above sea level. Much of the rest of the continent is very low-lying land, though sufficient variation in elevation provides for acceptable drainage, but makes for extensive networks of broad and slow running rivers ideal for canals. This terrain makes malarial fever and breakbone fever constant threats for the population, and extensive efforts to engage in the drainage of the land have been required by the government to facilitate further habitation.

Though the central plains have found themselves to some degree inhospitable due to the poor drainage, four regions beyond the highlands offer themselves to ease of habitation. The first of these is the western part of South Zealandia, comprising fourty percent of the land area of South Zealandia State. This area is rendered incredibly bountiful by the cool rainfall delivered continuously by the great easterlies which sweep around the Antarctic continent, and deliver rainfall in excess of 140 inches per year along the coasts, and considerable amounts in areas of the interior. But due to the height of the land, and the drainage afforded to the east by the Sambuhl swamps, the land lacks extensive swamps or marshes. Immense forests of coniferous trees of family Podocarpaceæ and broad-leaf evergreens cover this whole reach, and many of the lower-lying areas of the Zealandia Highlands as well. In this profusion of primeval bounty, an immense number of large bird species and unusual forms of mammals have prospered, as well as some of the rarest known reptilian species. Many have gone extinct due to the prodiguous spread of humanity; many remain. The Auckland islands to the southwest of this promontory show a trend from temperate rainforest to subarctic conditions over their full reach, and are a volcanic extension of the Zealandia Highlands chain.

To the immediate east, and before the Rehanoaka hills which split the centre of the southern continent, is the Sambuhl swamps. This immense concentration of swampland is twice the size of the Pripet Marshes of western Russia, and broadly comparable in diversity, being only very lightly habited. Beyond the Rehanoaka hills in turn is lowland near the coast which, being better facilitated in their drainage, and situated at a higher latitude with less rainfall, though still sufficient, affords an area of particular bounty, which has seen extensive colonization from the central parts of the Empire in recent years. To the northwest of this region is the very large Unohak Depression, which at one time was certainly an arm of the sea which was closed by volcanic activity and lays well below sea-level. It is now filled with a series of three major lakes, which will no doubt ultimately rise over æons to combine and form a new and great river to the sea, as no present means of drainage exists.

Now traversing the Zealandia highlands the Kra'taoi plateau affords itself an excellent position, being similarly afforded with quantities of immense rainfall, though not as great as the extreme southwestern reaches, with averages recorded in the range of 70 - 90 inches per year at the most, as the Tasman Islands serve as a barricade to these atmospheric concentrations. This area has long been the habitation of the Maori people who conquered the less sophisticated natives, though in this case the area has been given over entirely to the Maori variants of the Australis subspecies. Their tendency to adopt more to the farming of grains, introduced in quantity by the Chinese in the 1300s AD, has considerably changed the landscape and seen the felling of much of the once dense forests which covered this area. Directly below it, and comprising the rest of the central part of the continent, is another vast swamp, at least the size of the Sambuhl swamps and estimated to be somewhat larger, pinned between higher land and draining slowly to the east through broad coastal plains. Aggressive draining of this area has been commenced, in comparison to the pristine nature of the Sambuhl swamps. Though all directly connected, it bears no particular name, the Kætjhasti peoples having various appellations for different regions. The presence of this swamps and their easterly drainage means that the populations of central Zealandia are concentrated on the Kra'taoi plateau and the western coast.

The rest of the continent to the north is divided into two enormous peninsulas, the Tingfu'eh and the Enahouae. They are divided by an enormous bay formed by the subsidence of land in æons past, usually called the Orangetua Fjord, though the later term is incorrect, as it was not formed by glaciation. In both cases the land rises considerable, though there is more variation in the Tingfu'eh peninsula, which contains an extensive depression similar to the Unohak, though largely and only narrowly closed off from the sea, named the Willem Endracht, after the Dutchman whose exploration of the Orangetua afforded him the first sight of the depression. A myriad of thirty-one small lakes exist on its bottom, with high hills most prominent to the north and west. The Government has lately proposed studies into the feasibility of constructing a canal into depression, creating an artificial waterfall of a vast scale which would enable the generation of electric power, but these seems far beyond the present engineering capabilities of the Empire. The Enahouae peninsula affords a more generally high and less broken visage, rising in the far north to a plateau some 4,600 feet above sea level which contains on it Mount Paniae, reaching an elevation in turn of 9,972 feet. In this area the diversity of reptiles and birds is at its most extreme, and at least one species of giant birds persist in the highalnds. There is a sharp and strong divide between the western side, which is rain-shadowed by the high plateaus, and the eastern side, which is rainforest of a tropical nature, though with distinctive flora. In comparison, the Tingfu'eh peninsula has predominantly similar conditions to the Kætjh plains in the lowland, and the Great Dividing Range of Australia Major in the highlands, presumably from species having crossed over the narrow straits over time and establishing themselves strongly in the area, but also due to the Chinese and Malay colonists introducing all characteristics for the intensive cultivation of rice over many centuries.

The eastern territories of Kætjhasti, annexed as late as the early 1890s in the case of the New Hebrides and southern Solomons, are in those cases of volcanic origin and have a tropical or sub-tropical climate, though the only examples of the later are in the New Hebrides. Major eruptions have taken place, and the archipelagos are known to be extremely hostile in climate to whites, though the Malay populace of Kætjhasti has proved hardy in their efforts to administer and conquer the resisting tribes of the area despite the natural opposition provided by the usual jungle fevers. Further to the south are the Kermadec Islands, forming to the northeast a volcanic extension of the Zealandia Highlands as the Auckland Islands are a volcanic extension to the southwest. These islands are considerable in number and size among all those of Polynesia, but vary considerably in climate over their rugged and folding surfaces. Many of the southern islands have been populated by species from Zealandia, though the northerly islands have a predominance of the palm, and the introduction of the Polynesian pig is universal.

2. THE PEOPLE. The people, or peoples, of the Kætjhasti nation, provide an immense cross-section of the Malay and Pacific races beyond their more peculiar traits. Of the population as a whole, a plurality is of the Malay race in origin, numbering approximately fourty-five percent, and they are the dominant among the peoples to be discussed in their influence on culture and in the government of the state. More importantly, however, is the due consideration attended to the nature of the Kætjhasti. They have been previously argued to exist as the sole living subspecies of homo sapiens; recent evidence has however confirmed that they exist as a part of the human species, but one in a fundamental and irrevocable symbiotic relationship with the Kingdom Bacteria.

One of the most fundamental and immediately noticeable results of this symbiosis is that the primary races of Kætjhasti (irrespective of those on the fringes of the Empire who did not suffer infection) are entirely female. This peculiar social order was the result of the symbiosis in the form of a very well documented plague of the 1480s - 1490s AD, apparently introduced from the Tasman Islands by sailors, and attributed in the local Hindoo superstition to the wrath of Kali for the men having eaten meat. As the fantasy goes, a priestess offered herself up through immolation to Kali, and her wrath was relented, with the females of the sinful lands being allowed to survive through self-reproduction (See PARTHENOGENESIS). In general this has completely reordered all infected cultures, and created unique bonds over and above those of typical national identity which have allowed the Kætjhasti to form as a strong and unitary state body.