The grand jury that opted not to indict Cleveland police officers Timothy Loehmann and Frank Garmback in the shooting death of Tamir Rice never actually took a vote on the matter, according to the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor's Office.

What actually happened in the most significant grand jury hearing in county history isn't quite clear, and the mechanism by which the grand jury "declined to indict" — in Prosecutor Timothy McGinty's own words — is equally unclear.

At the conclusion of a typical grand jury hearing, there are two possible outcomes achieved via vote: a "true bill," which results in criminal charges and a case number in the court system, or a "no bill," which is a decision not to bring charges. A "no-bill notification" is signed and stamped and kept on record at the county clerk's office.

Though Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Timothy McGinty never explicitly said the grand jury voted not to indict — nor did he utter the phrase "no bill" — in his Dec. 28 press conference, he declared that that grand jury had declined to indict.

How, then, if not by voting?

After learning and confirming on Jan. 15 that there was no "no-bill notification" on file at the county clerk's office for the Tamir Rice grand jury proceedings, Scene formally requested the document officially showing the decision, however it was reached, and wherever said document might be. We were told that it didn't exist. Employees at both the clerk's and prosecutor's officers were unable to explain the lack of paperwork.

Tuesday, Scene spoke with Joe Frolik, the communications director for the Prosecutor's Office, who said no no-bill record exists because, "it's technically not a no-bill, because they didn't vote on charges."

He elaborated: “This was an investigative grand jury. This was kind of their role. Sometimes, a grand jury, after its investigation, will decide if there are no votes to be taken on charges.”

But how that decision was reached and the location of any record of that decision remain publicly unaccounted for. The term “investigative grand jury” appears nowhere in McGinty’s public statements and reports on the proceedings.

Professor Jonathan Witmer-Rich from the Cleveland-Marshall College of Law at Cleveland State, who specializes in criminal law, explains what that term means.

"Prosecutors sometimes use [grand juries] as investigative grand juries to determine whether any criminal wrongdoing has happened or not,” he said. “It happens with political corruption cases or very complicated investigations. The Tamir Rice case, that's how I believe the prosecutor viewed that grand jury. What the grand jury allows you to do is have the power to subpoena documents and call witnesses and have them testify under oath. It allows you to get all the information and investigate whether a crime has occurred. They're not different legal entities, but they are serving different functions and thus might behave differently.

"But if they don't hold a vote, how do they decide not to hold a vote? And would there be a record of that?” he continued. “It's not like the prosecutor has the power to prevent the grand jury from voting. If there was no vote on a bill in this case, the prosecutor might have influenced that —- he might have said there's no reason to even vote because we all agree, or something — but it's still the grand jury's decision. It ultimately has the power to consider the facts as they're aware of. Because of grand jury secrecy rules, though, we can't know what happened inside that room."

As for a case that went before a grand jury but didn't result in a vote, Witmer-Rich said, "I'm not aware of an example...It could happen, I suppose, but I've never heard anyone talk about that."

Professor Lewis Katz, a criminal law expert at the Case Western Reserve University School of Law, noted that investigative grand juries are ordinarily held in secret. In his view, the Tamir Rice grand jury was not investigative.

When informed that not only is that what the Prosecutor's Office said (i.e. that it was an investigative grand jury) but that no vote occurred at the end of the proceedings, Katz said, "I'm stunned."

He then raised a point hammered home by Rice family attorney Subodh Chandra during the grand jury's term: The two officers in question submitted statements under oath, and thus waived their Fifth Amendment rights, opening them up to questioning. If you view the grand jury as investigative — and thus make every use of subpoena power to get people to talk under oath — the fact that neither McGinty nor the grand jury got to cross-examine the officers and ask questions is strange — decidedly non-investigative. Katz suggested the grand jury might not have been informed of that possibility, probably because the Prosecutor's Office mistakenly viewed that the officers could reclaim their Fifth Amendment positions after submitting the statements.

"But by taking the oath and submitting statements," Katz said, "they waived it."

And if there was no vote at the end: "Then why go to the grand jury at all? Why was there one if they weren't asked to vote?"

When considering that question, McGinty’s past statements only become muddier.

In his own words on Dec. 28 (the day the decision was announced), McGinty said: "Based on the evidence they heard and on the law as it applies to police use of deadly force, the Grand Jury declined to bring criminal charges against Cleveland Police Officers Timothy Loehmann and Frank Garmback."

During the same Dec. 28 press conference McGinty touted his own decision in 2011 to "run for County Prosecutor to make our Criminal Justice System more transparent, professional and accountable."

Indeed, openness and honesty were prominent themes during his handling of the Tamir Rice case — he trumpeted transparency when releasing investigation records of the case to the public, including expert opinions his office commissioned — but his announcement on Dec. 28 turns out to have been remarkably opaque.

After all, news of a "no-bill" was reported and repeated around the world, the "no bill" portion being assumed by anyone covering the grand jury. Many outlets simply used McGinty's language — "declined to indict," "elected not to press charges" — but the assumption was that the decision was reached by a vote. That assumption is held to this day not only by outside observers, but by high-ranking judicial personnel within the Justice Center Complex.

Even without a vote, some documentation that explains what transpired should exist. It's the equivalent of a no-bill, Frolik told us, but added that his office didn't have the document in question.

He directed us to Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Judge Nancy McDonnell, who presided over the grand jury. Her office didn't have the document either, and the judge told Scene she had no comment on the matter.

We were then directed to the Cuyahoga County grand jury office. Wednesday morning, a clerk there told Scene that the "mysterious document" may or may not exist and that, even if it does, it could only be provided to us via court order by Administrative and Presiding Judge John J. Russo. And even with a court order, the clerk said, she might not be able to hand it over.

Russo, who spoke to Scene by phone, professed to be as confused as we were. "When you say 'document,' I'm not sure what you mean. I don't know what that is. It's either a true bill or a no bill," he said.

But actually, no.

His staff determined Wednesday that a “no-bill” had never been filed. Russo said he had a "judges meeting" Wednesday afternoon, at which he intended to seek clarification from Judge Nancy McDonnell about what precisely was filed.

We’re awaiting word both on the content of that discussion and the subsequent question of a court order that would pry loose the mysterious document.

Reached Tuesday, Subodh Chandra, the local attorney for the Rice family, said that the whole process has been "irregular.” He said he and his team had asked the county if the grand jury members were led through each possible charge for a vote or whether there was one overarching vote on all charges, but never received an answer. When informed no vote of any kind took place, Chandra said: "If it is true that the prosecutor didn't even call for an up or down vote on potential criminal charges, including aggravated murder, then it is truly the ultimate insult to the Rice family,” Chandra said, “that the prosecutor didn't even think it mattered to bring the grand jury proceedings to their proper conclusion."

***

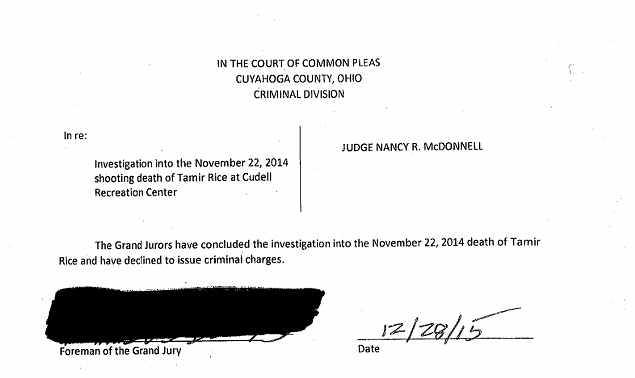

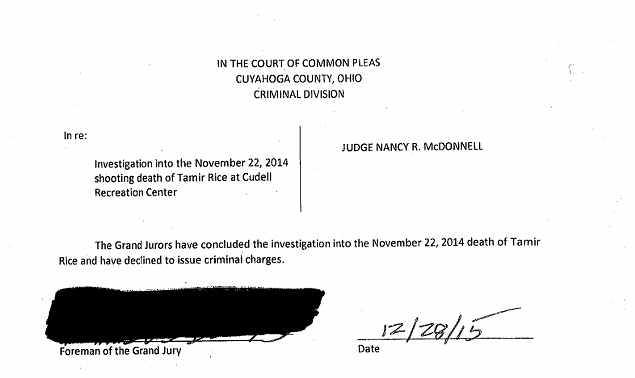

Update (6:00 p.m.): After two days of calls, the Prosecutor's Office produced the document in question that states the grand jurors declined to issue criminal charges.

How that decision was made — i.e. a record of what the vote was, unanimous or mixed — is still unclear.

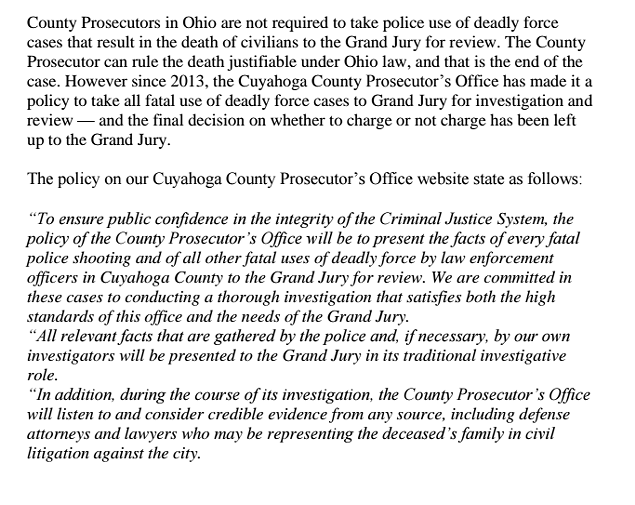

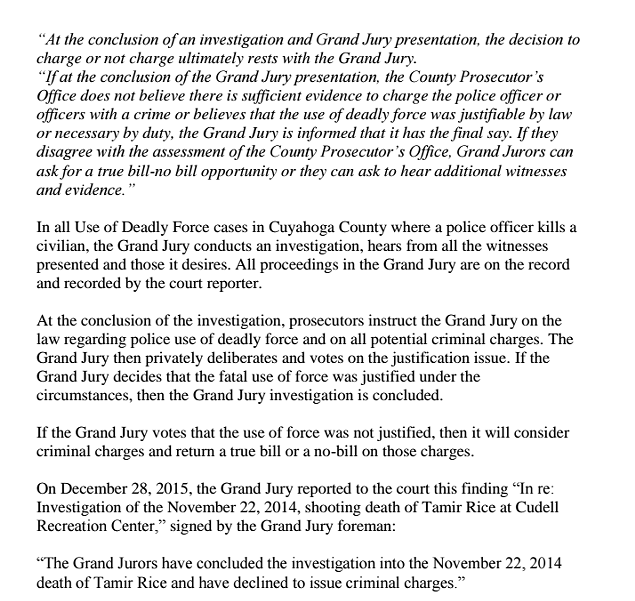

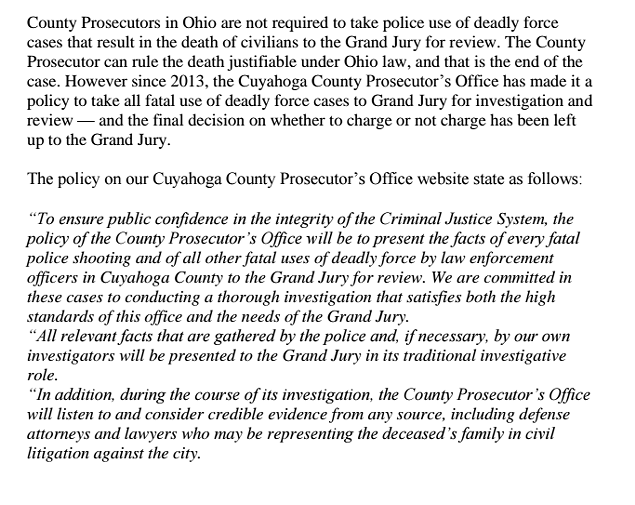

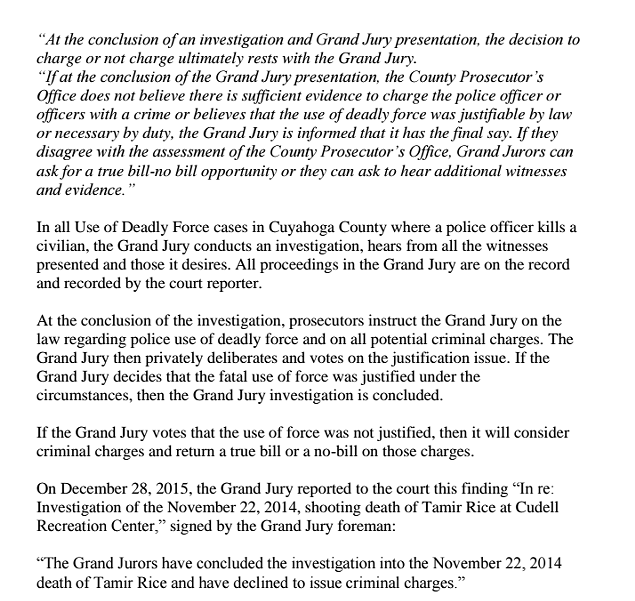

McGinty's office issued a statement in response to the story pointing toward the policy on police use of deadly force cases involving civilians. The full statement is below; the short version is this: 1) It insists all possible charges are read to the grand jury (that McGinty did or did not do that is unclear), and 2) It's up to the grand jury to disagree with the prosecutor if the prosecutor is not against pursuing charges: The grand jury has to ask for a charge to vote on a no-bill or true bill.

A reminder that court officials, members of the Prosecutor's Office, lawyers and just about everyone else had no idea that this was what happened in the Rice case. Nor does it address the deficiencies in a policy that asks the grand jury to disagree with the Prosecutor's recommendation and opinion in order to pursue — or even vote — on charges.

***

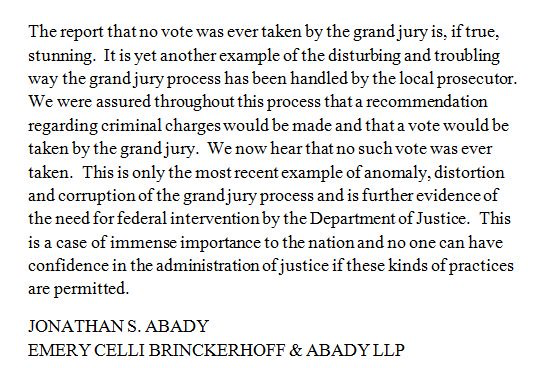

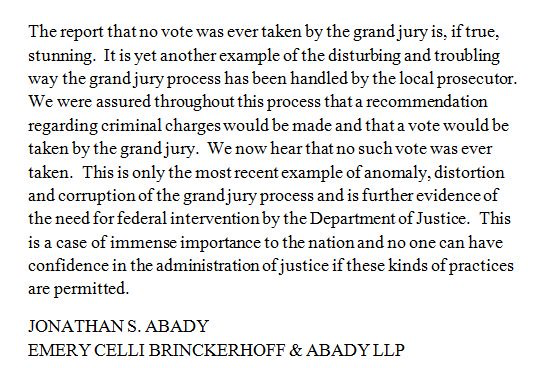

Update II (6:26 p.m.): Attorney Jonathan S. Abady, a lawyer for Samaria Rice, has issued a statement. It emphasizes, in part, that the family was ensured that a vote of the grand jury would take place.

Update III: The prosecutor's office now says that a vote was taken by the grand jury on the issue of whether the shooting was justified. The Washington Post got an explanation from McGinty spokesman Joe Frolik, who also told the paper that while he told Scene his office didn't have a copy of the document in question, someone did find a copy late Wednesday afternoon after this story was originally published.