The Admiralty

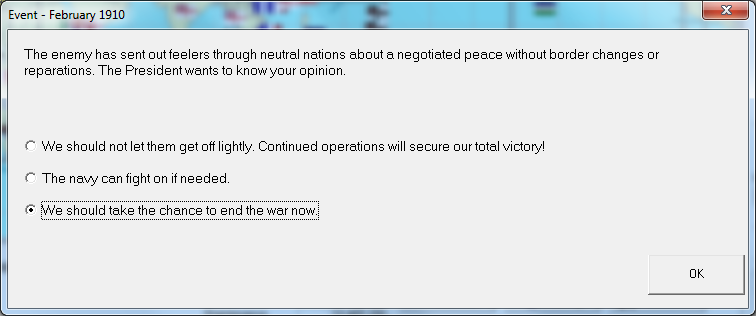

Portland, Federal District

13 March 1910

Sunday was supposed to be a day of rest. But there was no such thing in war.

Admiral Garrett had, indeed, insisted that weekends no longer be considered off days. In peacetime only a small staff would have been on rotating duty to ensure someone could answer emergency wires. Now it was fully staffed. Men were given only one day a week off and only when no major operations were scheduled.

Every man save Admiral Garrett, who insisted on spending at least six hours a day in his office.

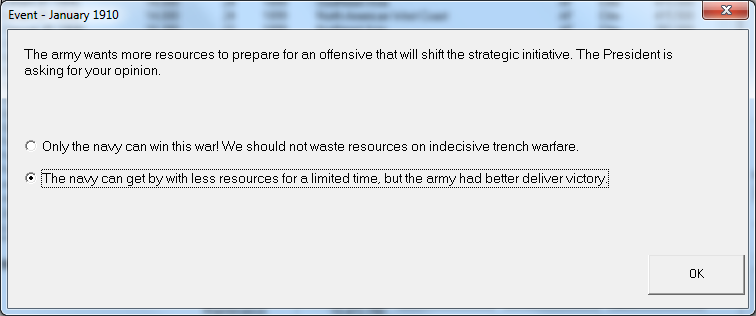

There was little going on, certainly. At least from the perspective of war-making events. All of the attention was on France and the Spring Offensive. But just because there was no recent naval battle didn't mean there was no work to be done. Promotion boards had to have their findings signed off on. Commissions had to be finalized for Presidential approval. Budgets to the Offices and Departments had to be allocated. There was a lot of discussion and signing and reading to be done for the Chief of Naval Operations, and Admiral Garrett never wanted for work.

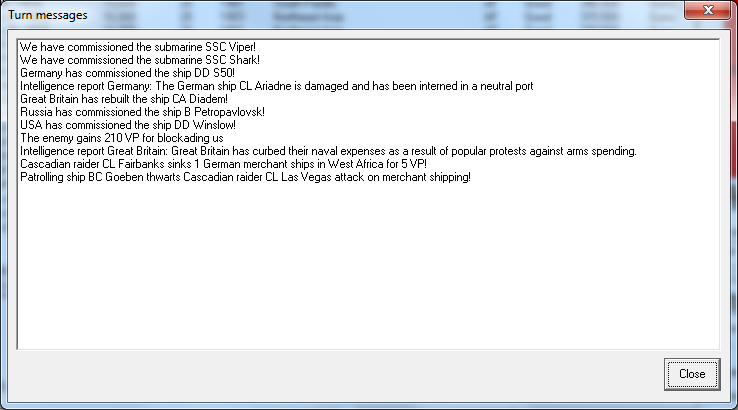

Some of the reports crossing his desk were distressing. Socialist agitation in the Navy was growing. The sailors were frustrated by the extended time at sea, the lack of a battle, and any sign of the war ending. He could sympathize, but at the same time he could not condone actual mutiny, and his orders to Litchfield and MacCallister reflected that.

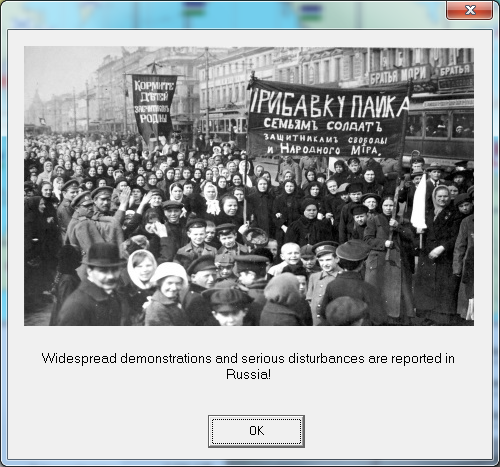

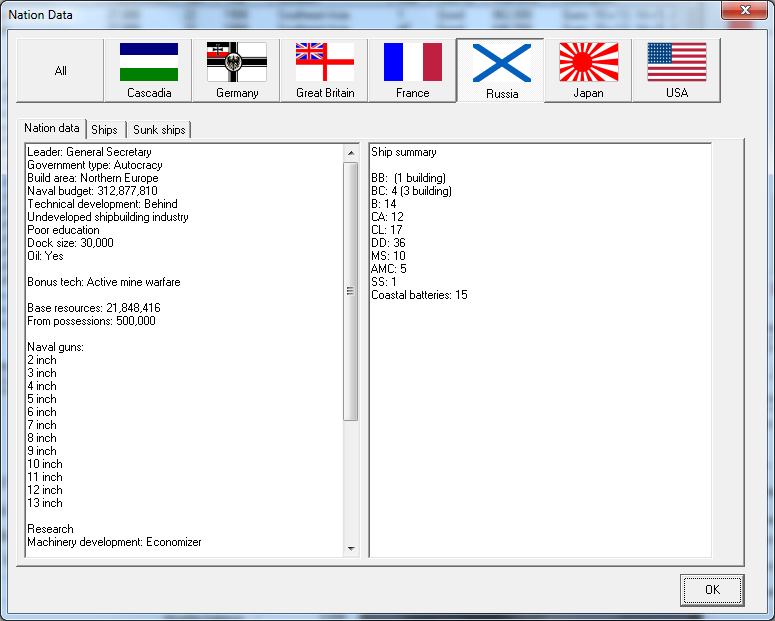

Intelligence reports indicated growing disruptions in Russia. Groups with names like "Menshevik" and "Bolshevik" were meeting and plotting, according to special sources. The Russian populace hated the war and wanted it over. Time would tell if the Tsar broke from Germany in time to save his throne.

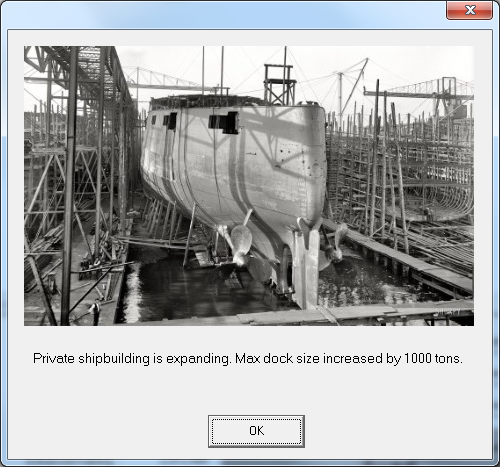

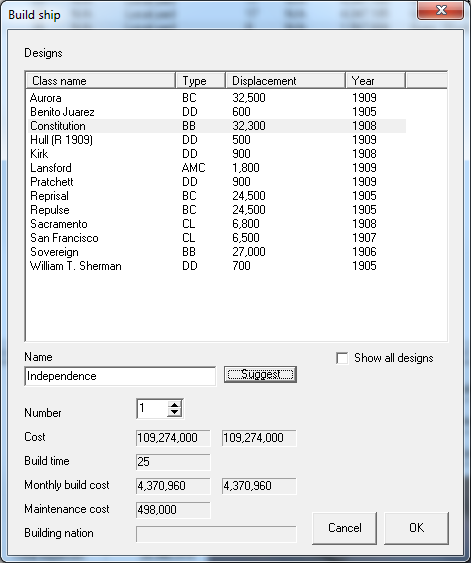

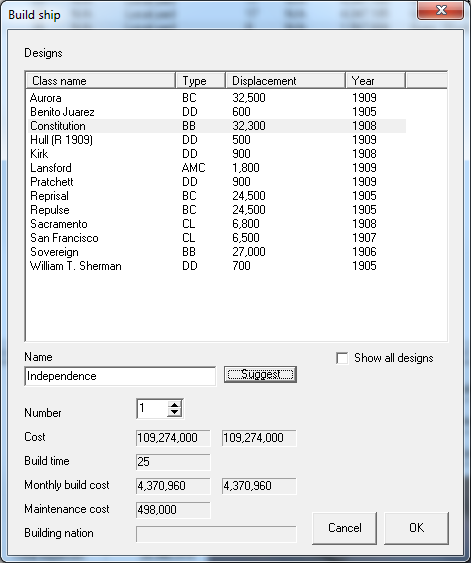

And finally there were the contracts. Careful budget consideration had led Admiral Garrett to approve a fourth

Constitution-class battleship, the

Independence. It would be laid toward the end of April, when the budget allowed. This would provide Cascadia with a solid battle line for the next several years.

There was a knock on his door and it opened a moment later. He looked up and nodded at Yeomen Rodriguez, a pretty young lady from Lower California that had enlisted in the Womens' auxiliary, freeing up men for combat duty. Her skin had the tanned complexion of mixed birth, the

mestizos as the Mexicans and others called them, and her dark eyes were similar in tone to Rachel's.

Standing beside her, looking to enter the room, was an Army officer. Major John Trimble was a staff courier who often brought notes from the Army Chiefs of Staff to the Admiralty. He saluted upon entering the room. "At ease," the Admiral replied, saluting as well. "What do you have for me today?"

"General Landers wanted you to see this, sir," Trimble replied soberly. He offered a paper. "Before it's printed in the papers."

WIth a foreboding sense of unease, the Admiral accepted the paper. He wondered what it could be in the moments before he glanced. Had the Army uncovered a radical leftist plot for a revolution?

Or was it…?

He read over the paper.

And for a moment, he stopped breathing.

"There is nothing more…?", he asked with a hoarse voice.

"No sir."

The Admiral looked very old and tired as he almost fell into his chair. The two people attending him couldn't help but notice how white his face had gone. "Thank you," he managed. "My thanks to General Landers for his consideration. You are dismissed, Major."

"Yes sir." Trimble saluted once and departed.

For several seconds the Admiral did not move. When he did, it was to stand again. "Yeoman."

"Sir?"

"I am going home early today," he told her. His voice was still hoarse. "Inform Admiral Cousland, please. I can be reached by courier if it is necessary."

The young woman nodded. She had the decency not to ask what was wrong. "Right away, sir."

Just as the war had broken out, new orders from the Administration had resulted in the services buying a small fleet of Ford automobiles for their high officials, to be driven by servicemen. This was a measure for security's sake.

It relieved the Admiral of the need to endure a talkative cab driver. The Army corporal assigned to the driving service remained silent while taking him across the Willamette and to the family's home.

Josephine had moved on recently. A young man had married her, an engineering student at the National University thus exempted from the draft, and she had found a job at the University to be closer to him. Her replacement was a Chinese immigrant girl named Mei Ling. The sixteen year old girl knew enough English to function with the family and serve to satisfy Rachel's interest in learning yet another language.

She took his coat without asking and informed him that his wife was in the parlor, reading with Gabbie. The Admiral walked through the hall and into the parlor with the message still clasped in his hand.

Rachel looked up as he entered. After a moment Gabbie did as well. "You're home early…" In a moment Gabbie was off her mother's lap, still holding the picture book, and Rachel was standing up. "What's…" A hand went to her mouth to try, and fail, to stifle the gasp that came. "Thomas?"

He swallowed. And nodded.

Tears were forming in her eyes. "Is… is he…"

"Wounded. Badly. They don't know if he will survive."

A wail of anguish was her reply. Rachel went up to him and threw her arms around the Admiral, who did the same with her.

And they wept, together, for the fate of their child.

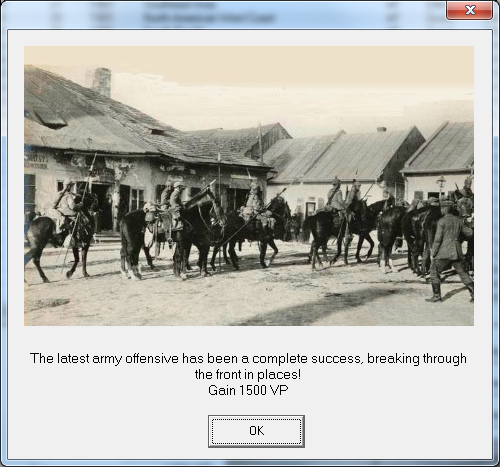

The Allied attack on March 9th caught the German and Russian commands by surprise. They had not believed the Allies would attack so soon in the spring, when even the brief dry spell might be quickly replaced by rainy weather that would turn the churned battlefields into mud.

What had also taken them by surprise was the new Cascadian armored tractors. Referred to simply as "Army Armored Tractor Mark I" and called "tanks" by the enlisted men for the cover names assigned to the machines, the vehicle was widely deployed in the dozens at Amanvillers and other key points in the Lorraine section of the front. The French perfected their own techniques based upon studies done by Colonel Henri Petain, employing forward advance parties to slip into no man's land and cut wires under cover of darkness, and to attack the German trenches with storm tactics before dawn to signal the main advance.

The Germans were more prepared for the latter, as they were exploring similar tactics, but nothing prepared the Russo-German forces in Lorraine for Cascadia's new weapon.

It was nevertheless a day of hard fighting in the plains west of Metz, as the Germans and Russians fought hard to repel the Franco-Cascadian attack. Further to the north, Russian units joined their brothers serving in the Far East by facing the Japanese Expeditionary Army, now enlarged to two armies with five Corps overall.

Allied casualties varied from moderate to heavy in various zones, but the tanks proved decisive. The Russo-German lines at Amanvillers were breached in multiple places by the tanks. Although many would succumb to mines, lucky artillery fire, or mechanical failure before the day was over, the breach in the line allowed the Cascadian 4th Army, spearheaded by the 8th Guards Regiment, to break into the Russo-German rear. The town fell by the end of the day's fighting.

Through the next several days, repaired tanks and fresh ones brought up to the front allowed the Allies to keep the enemy from recovering their poise. A Russian counter-attack against the 4th Army's northern flank was met and crushed by the 1st Army - and again the 2nd Cascadian Guards Regiment earned their nickname of "The Iron Wall" - that had been slipped through the breach behind the 4th Army.

The collapse of the Russian counter-attack presaged the ultimate disaster. By the 13th of March, Field Marshal von Moltke - von Schilieffen's replacement as German Army Chief of Staff - was receiving the first reports of total Russian collapse. The Russian troops, frightened by the difficulty in knocking out Cascadian tanks (indeed many refused to believe they could be defeated) and angry at fighting a war they perceived to be for Germany's gain, were melting away from the front. The Japanese maintained steady, if sometimes bloody, progress across the border with Luxembourg, and the Cascadian 2nd Army was now making headway into the gap between the Japanese and the Cascadian 1st Army. German reserves had checked the Cascadian 4th Army east-southeast of Amanvillers, but now the 1st Army's movement meant the German forces were being flanked.

Von Moltke had no choice - to save his troops still holding back the Cascadian 3rd and 7th Armies and the French 10th and 11th, he ordered a retreat and a rushing of reserves north. But the reserves had to come from within Germany - he didn't dare pull units from Alsace where, while holding the French with heavy losses, the Germans were nevertheless fully engaged. Bringing troops out from Alsace could permit French breakthroughs there as well. As it was, he was doing everything he could to keep the enemy from Metz.

For much of the month, it looked like he would succeed. The dry weather broke on the 15th and rain poured for the next three days. The Cascadian tanks sank into the mud the fighting had churned up and the Allied offensive ground to a halt. More reserves were brought up and the Russian armies had time to recover.

But the Russians needed more than three days to recover from the shock to their morale. And the tenacious insistence of General Simon D. Hartfield, commander of the Cascadian 2nd Army, meant that said army continued to launch attacks on the Russian forces ahead of them, pushing them inch by bloody, mud-spattered inch. "Heartless" Hartfield would be hated in Cascadia and among his men for his bloody single-mindedness, but his exhausted army and their losses nevertheless served a key purpose in keeping the Russians from recovering. Several Russian officers turned to shooting shirkers and deserters to staunch the flow of broken men from the front.

Then the wet weather broke again. Sunny skies prevailed. After a day of dry conditions the mud dried enough that the Allied armies resumed their advance. The collapse of the Russian armies forced von Moltke to race troops north to protect the Saar and other targets. But with the French pressing him hard in Alsace and the Franco-Cascadian advance in Lorrraine gaining steady mileage, he simply didn't have the troops to hold everything. Not until the German army had more divisions available.

In Berlin there was consternation at the situation, not to mention the anger at Russia for the failure of the Russian armies. Germany had reduced callups to their own Army to prevent worsening the social unrest that she, like all the other participants in the war, was suffering. But now she lacked the manpower to quickly make up for the Russian failure.

In their desperation, the Germans decided to unveil their own secret weapon early. Authorization was given to the German artillery on the front to start firing special munitions.

The first gas attacks caught the Allies by surprise. Gas had been contemplated as a possibility. But for the moment it seemed neither side was willing to employ the terrible weapon.

Now mustard gas was falling in large quantities on Franco-Cascadian troops marching toward Metz. The Allies rushed to find a suitable gas mask model and put it into quantities for the troops.

In the short-term, the attack stood a great chance of utterly stopping the Allied advance. In fact, it should have.

If not for the wind.

As the first day of shelling finished, the wind shifted. It began to blow steadily from the northwest. That is, it was roughly on the backs of the Allies and toward the Germans. Confused orders to stop firing reached those guns as the gas clouds continued to descend upon German troops who were not yet as protected.

Even the German troops panicked as their own weapon went to work against them. They had no adequate defense against the gas. Many broke and fled.

Mile by mile the fighting continued. The newspaper reports traveled around the world by wire.

The Times called it "The bloodiest spring in world history". The

Washington Post was so horrified by the reports coming in from their correspondents that they practiced self-censorship for fear of public outrage over the most gruesome of the examples. The International Red Cross readied plentiful supplies to aid refugees from the fighting and to succor troops from both sides.

WIth both sides having suffered casualties reaching the 100,000 mark per involved nation - save Japan, which currently had 63,000 casualties in Europe - the voices crying for the fighting to end intensified. In the end, the great moment came on the 30th of March when, after three weeks of intense campaigning and battle, elements of the Cascadian 4th Army arrived at the city of Metz.

Metz was the center of the part of Lorraine that had been severed from France in 1871. It was the heart of the French-majority region of Elsass-Lothringen, the German territory carved out from their winnings in the Franco-Prussian War. It had an old fortress and sat on the Moselle River, the heart of the territory here.

German troops did occupy the old fortress and briefly use it against Allied troops. The German commander soon realized his situation and decided that preserving his men was more important than a last minute, last night stand. He slipped his troops out that night.

The result was reported on April 1st with great exultation by the pro-Administration

Oregonian.

ARMY TAKES METZ

Cascadian, French soldiers liberate Lorraine capital from German forces!

Citizens lined the streets of the French city of Metz as Cascadian and French troops marched by. The soldiers, weary as they were, kept their heads high on the march. Officers moved into the city hall and lowered the German Empire's flag, raising the French tricolor to once more signal to the people that they were one with their homeland. General Joffre, in a mark of respect, permitted Cascadian troops the honor of first occupying the old fortress at Metz, and above the fortress the Cascadian tricolor joined the French tricolor to mark the crowning success of this long month of March, 1910.

Officials in the War Office reported elation in the Government upon receipt of General Parker's wire on the liberation of Metz. "This day will be remembered in the history of our nation," insisted Senator Jake Roberts, the Populist War Secretary. "The Cascadian Army has proven itself worthy to march with the greatest armies of Europe."

The defeatist Socialists have yet to respond to this latest setback to their…."

Even before the fall of Metz, the ongoing fighting and the hardships facing the nation sparked demonstrations across Germany in favor of suing for peace. The SDP argued in the

Reichstag that with the Marianas revolt broken, the need for war had ended and Germany stood only to lose if they kept up the war. "Should we lose parts of the Fatherland over a port in China?", one deputy of the SDP asked rhetorically, referencing the German government's refusal to accept a peace that did not include Cascadia returning Kiautschou Bay to the German Empire.

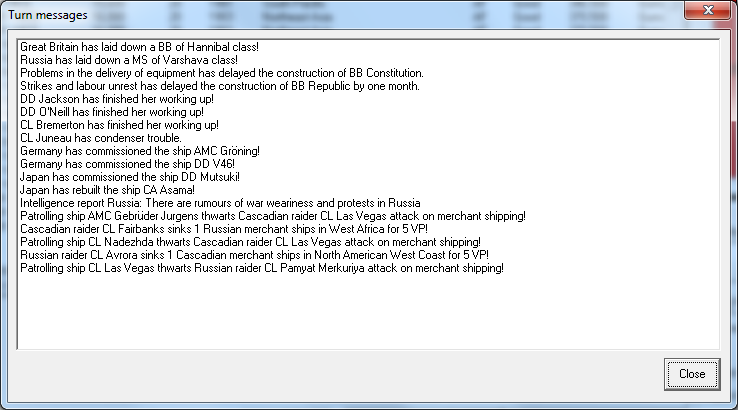

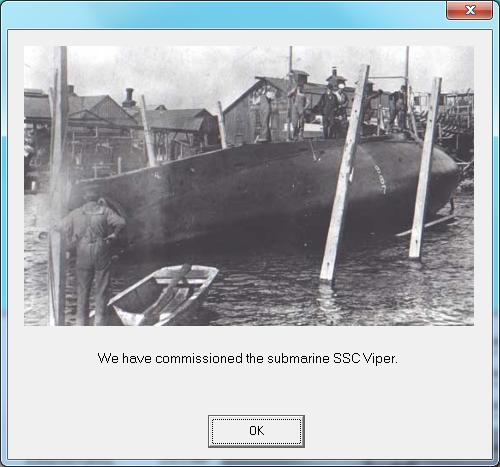

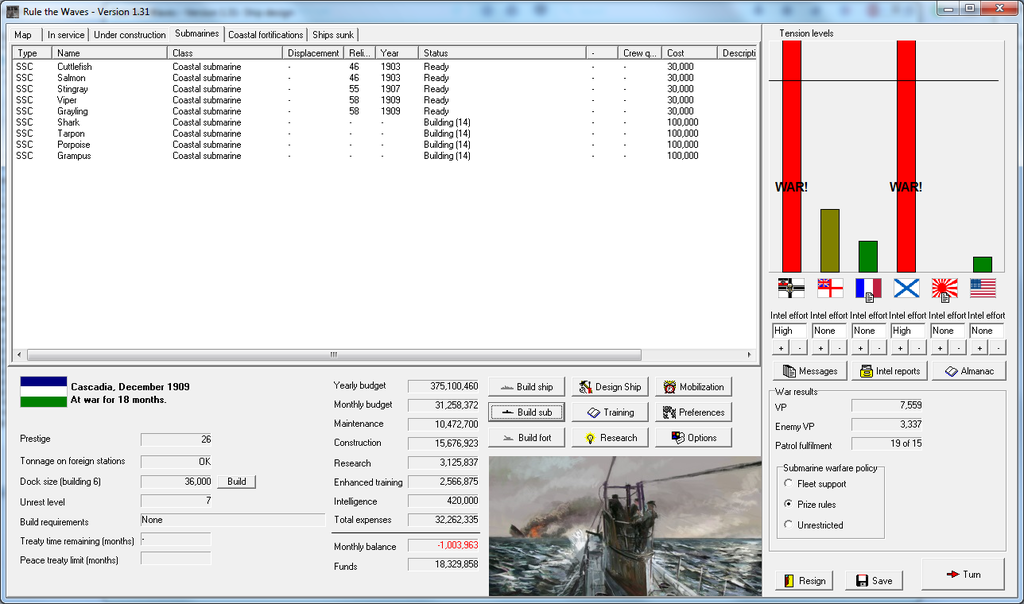

Naval engineers working with the Submersibles Department of the Design Office reported they had developed improved diving gear for new Cascadian submersibles.

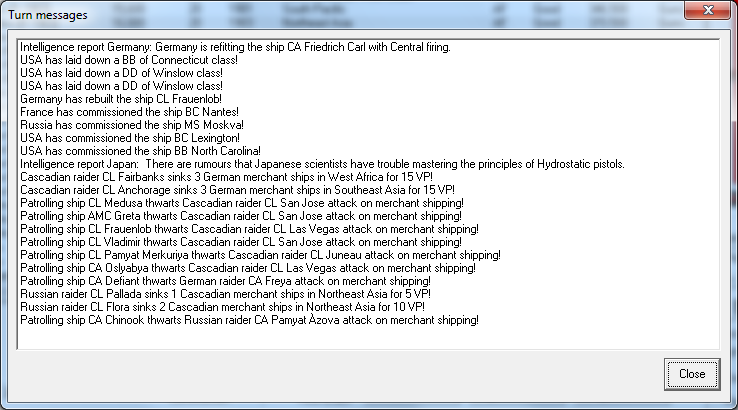

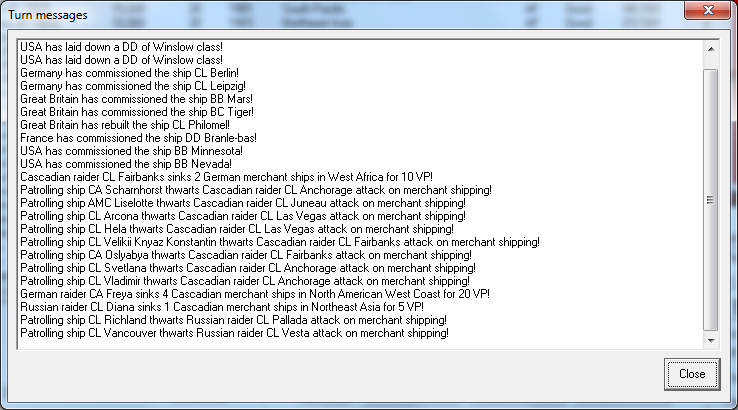

A German submersible sank a Cascadian transport ship near Le Havre.

The Japanese successfully seized a bridgehead over the Yalu River, inflicting thousands of casualties on Russia's Far Eastern armies.

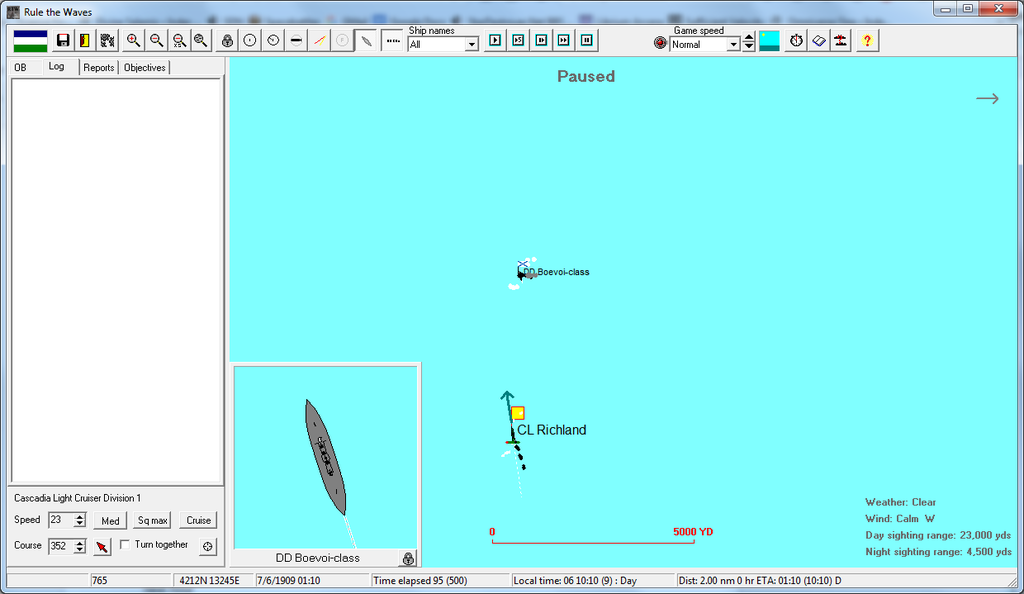

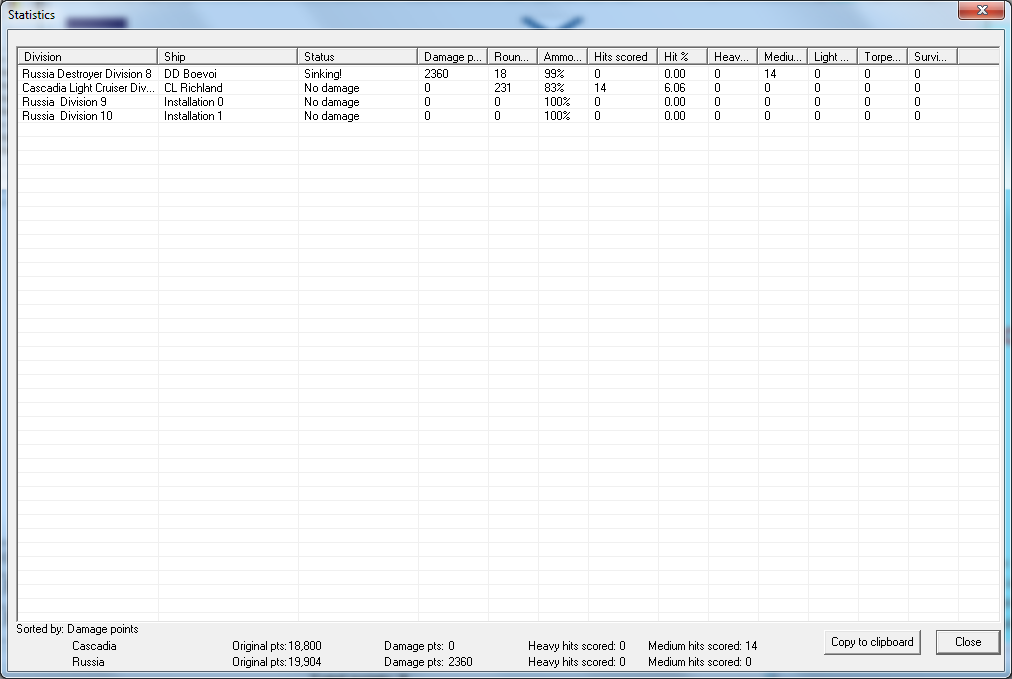

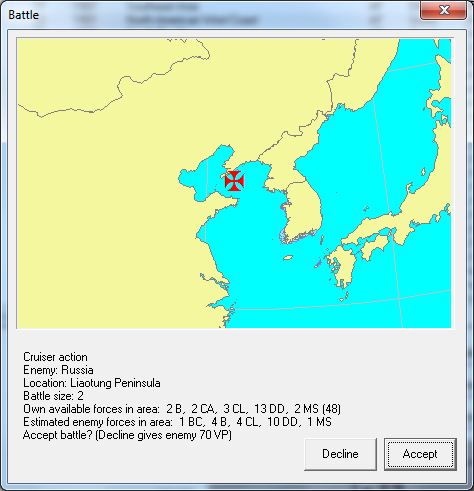

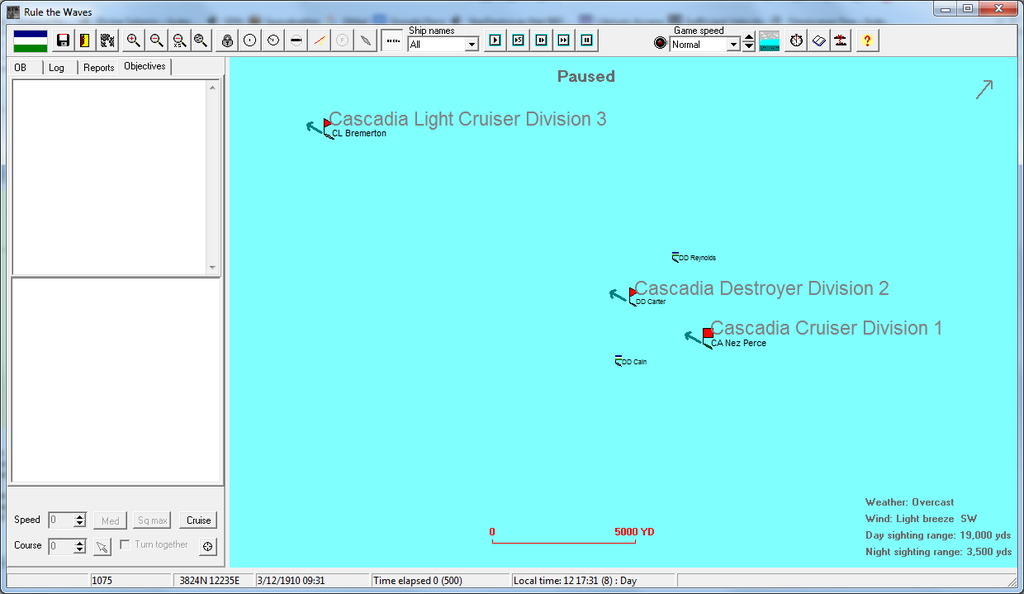

The

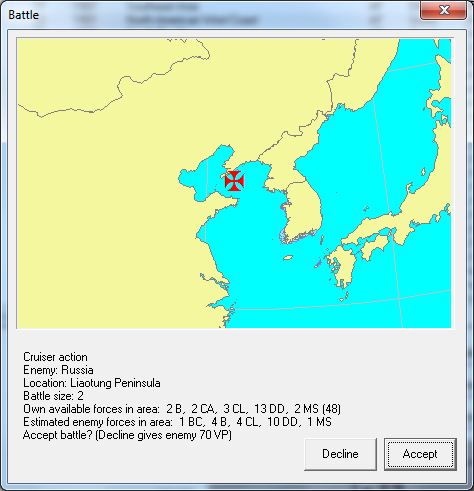

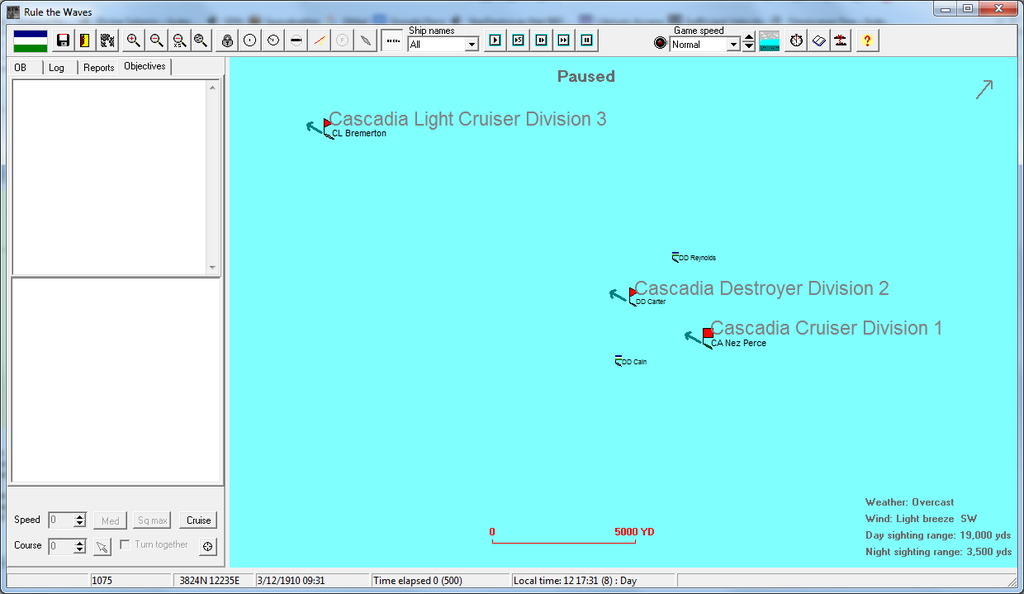

Nez Perce led a force near Liaotung Peninsula to find any Russian ships still operating out of Port Arthur. After hours with no visual contact, the Cascadian forces withdrew.

The bloody battlefield successes in France nevertheless took their toll back home. The Socialist Party held several more anti-war rallies. This time there was a further air of menace. Representative Charleton of Seattle went even further than Flagg, declaring that if the government continued to wage a war against the wishes of the people, "the people have a right to wage a war on the government". This not-so-veiled call for the anti-war movement to become revolutionary was both indicative of Charleton's growing adhesion to the Trotskyist-Leninist school of Socialist thought (that is, revolutionary Communism) and the frustration in the urban industrial cities at the Government's inability to restore peace. While the Cascadian merchant marine was still very intact despite some steady losses, insurance rates were hiking the prices of shipped goods and thus the prices in stores for imported goods and produce. Rising food prices and large casualty lists were turning the urban population against the war and against the government.

This time Attorney-General Caldwell had his way. Charleton had stepped beyond anti-war sentiment to revolutionary conflict inside the nation. Citing the National Protection clauses of the various enabled War Powers decrees, Caldwell had the National Marshals arrest the raging Congressman.

The arrest put Flagg in a tight spot. If he protested it, enemies would be able to accuse him of supporting Charleton's aggressive posture. If he said nothing, not only was he abandoning a party member to arrest, he was threatening a schism in the party just as popular fury made his intention to overturn the Government a reality. Ultimately, he protested the arrest on procedural grounds while distancing himself from Charleton's calls for violence.

The unrest was even spreading into the Navy. A Conservative officer in Admiral Litchfield's command, Commander Davison, reported to the Admiralty that Socialists drafted into the fleet had begun distributing anti-war leaflets even on the foreign stations and that some of the sailors were growing discontent with the war. The order came back from Admiral Garrett to maintain watches for mutinies but to not crack down immediately, lest it spark even wider mutinies from the sailors.

Unrest at 8

Joint Allied Army Hospital

Verdun, France

26 March 1910

Thomas opened his eyes.

Something immediately felt wrong. Something was off. His throat was parched dry. The light was too bright. And his stomach ached with how empty it was.

He gently moved his head and could see the beds to one side, and then to the other. A small table was beside him with medical instruments and such on it. The men in the other beds were in various states. Awake, asleep, sobbing in pain, staring into space…

The muscles in his body protested when he tried to sit up. He could hear feet clattering on the ground. "No, no," a woman's voice cried. "You musn't!"

A woman in white walked swiftly to his side. A nurse, in starch white, with dark hair done up in a bun and bright blue eyes that Thomas thought he could get lost in. He tried and failed to think of the last time he had seen such a gorgeous girl.

Her face betrayed concern as she put a hand on him. "You are still weak," she insisted. Her French accent was fairly thick "You are so very fortunate to be here with us, you mustn't push yourself."

Thomas blinked. And it felt weird. Like something was wrong. He reached up with his left hand and pressed it against his left eye. He felt only cloth.

But the feeling was also wrong. His fingers. Why couldn't he…?

His left hand moved into his vision. Thomas gasped in horror.

His hand was wrapped in a bandage as well. And two of his fingers were

gone.

"Yes. Yes, you… please calm down…"

"My hand," Thomas whimpered. "What happened to…?"

"You lost two fingers and some of the hand below," she informed him gently. "And your left eye. The doctors were able to save your left leg."

Thomas heard her say that. It registered. But still… his hand and his

eye. He'd lost an

eye?!

"Calm yourself. Your wounds still need time to heal," the nurse insisted. She took his right hand and left hand and held them in hers.

For several more moments Thomas continued to heave. He was incredulous. Panicked. And he could feel the weakness inside of him, hunger and thirst warring for attention, muscles unwilling to move just yet…

He had to gain control. He had to focus his mind. He had to grab on to something…

The thought went to his lips without his mind quite having time to catch himself.

"You are the most beautiful woman I've ever seen," he said.

The nurse blushed faintly and smiled at him. Thomas blinked and blushed as well. "I… I'm sorry, I…"

"It is quite alright," she laughed. Her accent gave her words an alluring, exotic tone. "I understand. Now that you are awake, I must inform the surgeons. Is there anything you need first?"

"Food and something to drink," Thomas replied immediately, his physical needs demanding the attention. After a moment he considered things. "And… if you can get me a pen and some paper and maybe an envelope…"

"A letter home,

oui? Yes?" The nurse smiled sweetly. "Of course, Let me go to the kitchens and get you some soup and water. And I shall see about the rest."

Thomas nodded. She turned away. Before she took a couple of steps he remembered a detail that had nagged him. "Wait… what's your name?"

She looked back to him. A smile crossed her face. "Anne-Marie Leveaux," she said. "You are Thomas Garrett, I believe?"

The way she said his name reminded him of the way his Pappi - his grandfather Vallejo - pronounced it. "Yes," he said. "That's me."

She nodded and continued on. And Thomas was left to his thoughts.

April 1910

After the fall of Metz the Allied offensive continued on. But the energies of the French, Cascadian, and Japanese armies had ebbed after a month of savage combat. The Cascadian 2nd and 4th Armies were more than decimated by the losses they had endured, with 2nd Army having entire regiments depleted to the size of companies by combat casualties. General Parker reported to General Joffre that his troops could not sustain their forward movement. If they did not relent now and dig in, a German counterattack could easily reclaim Metz.

The French command bristled at this, believing a German collapse imminent that would carry them all the way to Strassburg and the Rhine. This was an alarming display of some of the disconnect between the French staff command and their field armies. The French had suffered the highest casualties of the spring fighting and their armies were just as exhausted. Gains in Alsace were measured in yards, and the Germans now had the Moselle River for further natural defense in Lorraine.

But Joffre was under pressure. Georges Clemenceau was leading a charge to replace the current government with one even more hawkish, and Joffre's civilian superiors were desperate for another victory to stave him off for fear that a hawkish government might yet provoke further social unrest. The proposal was made to move fresh French troops, in the 14th and 16th Armies, and to push north of the city toward the Saar. This would put them against the demoralized Russian forces that were deserting to the Allies steadily, reporting terrible conditions and near-mutiny in the ranks. A reluctant General Parker agreed to commit two brigades of the 1st Army to supporting the French assault scheduled toward the end of the month.

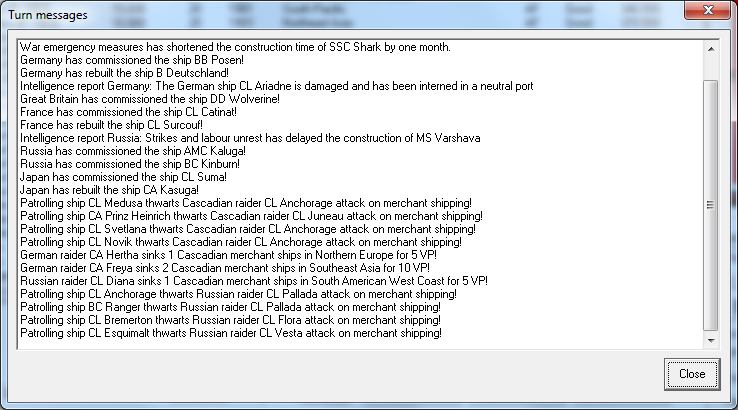

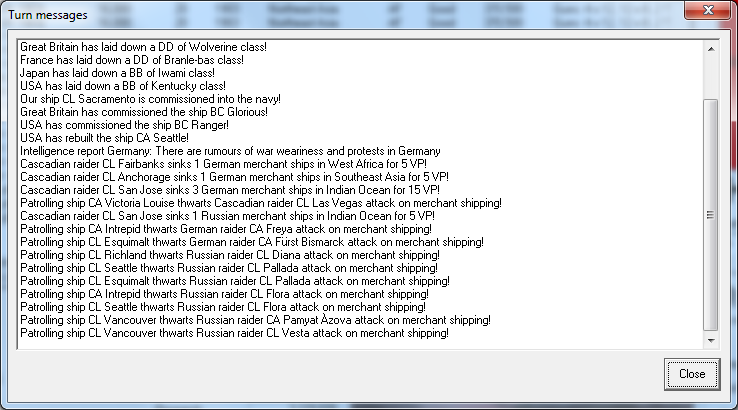

The new scout cruiser

Sacramento was commissioned.

Further examination of captured German shells from Tsingtao proved of assistance to Naval Ordnance in improving AP shell design.

Metallurgy experts provided the Navy with superior methods in ensuring quality in the forging of naval armor.

The German cruiser

Amazone was interned after exhausting her coal bunkers.

The situation in Russia was deceptively quiet for much of the month. Armed soldiers were employed to keep the peace in St. Petersburg, Moscow, and other major Russian cities. The Tsar's Government issued public statements urging the public to keep their faith in the war effort. Pro-government publications gleefully reported news of the "Socialist rabble uprisings" supposedly crippling the Cascadian and French countrysides while news of their own army's problems in Alsace-Lorraine and the Far East were carefully censored. As the month went on without word of major problems, the Russian government felt confidence rising again, not realizing just what the quiet portended.

Meanwhile the French prepared to launch their offensive on May 3rd, looking to punch the Russian lines open.

But unknown to them, or to the Russian deserters that survived no man's land to surrender, von Moltke had assigned two fresh German armies a couple of miles to the rear of the Russian lines. While his commanders urged him to attack through the Russians, the German commander-in-chief instead prepared plans for a counter-attack to fall upon the Cascadian 2nd Army one the French advance had exhausted itself. Once that casualty-ridden, beleaguered formation had cracked and collapsed, the Germans would be able to outflank the extended, weakened French forces and maneuver into northern Lorraine. If they could threaten the road link to Metz, Germany might force the Allies to retreat and reclaim what had been lost.

The

Hochseeflotte steamed out to meet the

Marine Nationale in a battle near Texel off the Dutch coast. During the battle the French destroyer

Francisque was sunk by German shellfire. The exchange went in France's favor, however, with the torpedoing and sinking of the battleship

Zähringen.

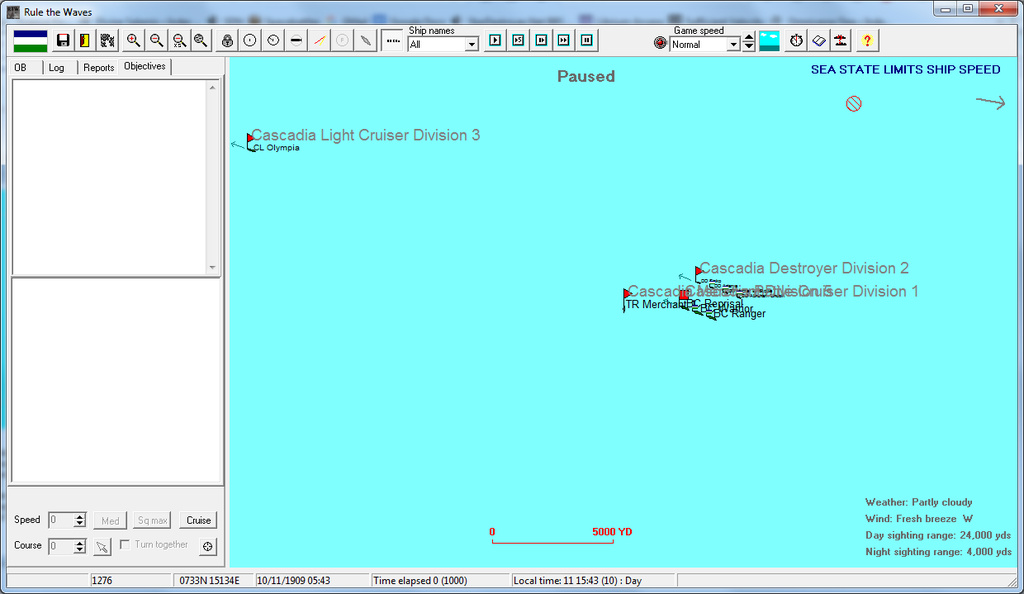

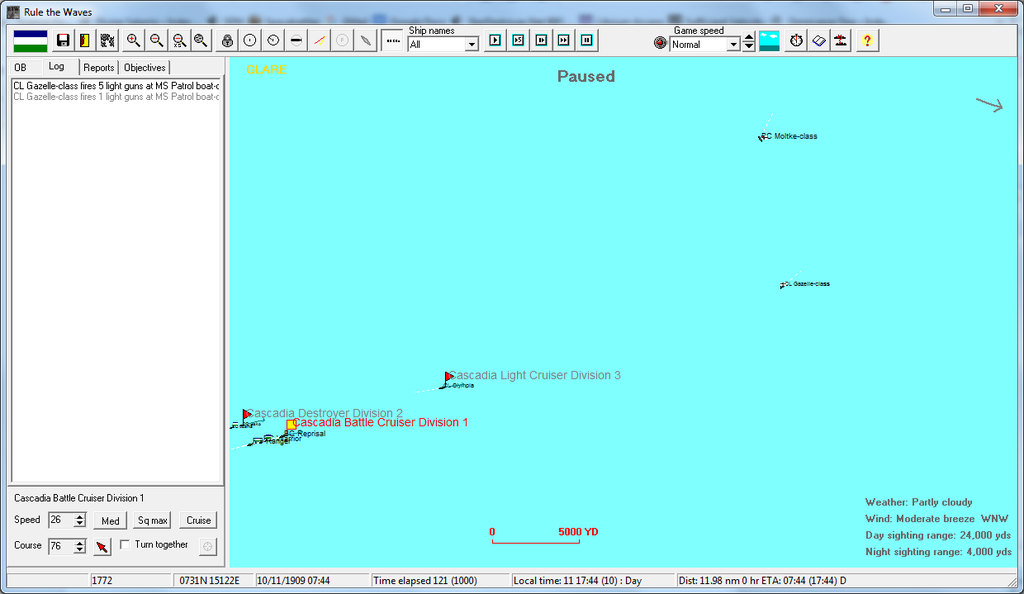

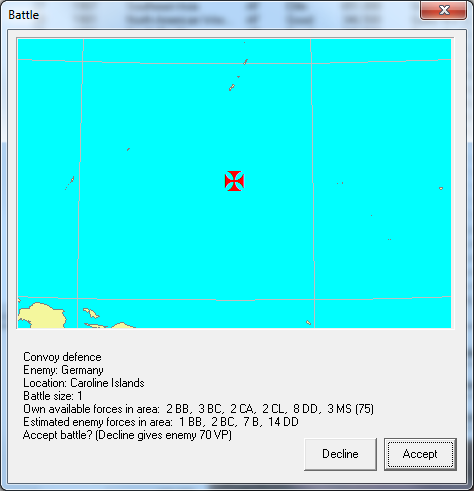

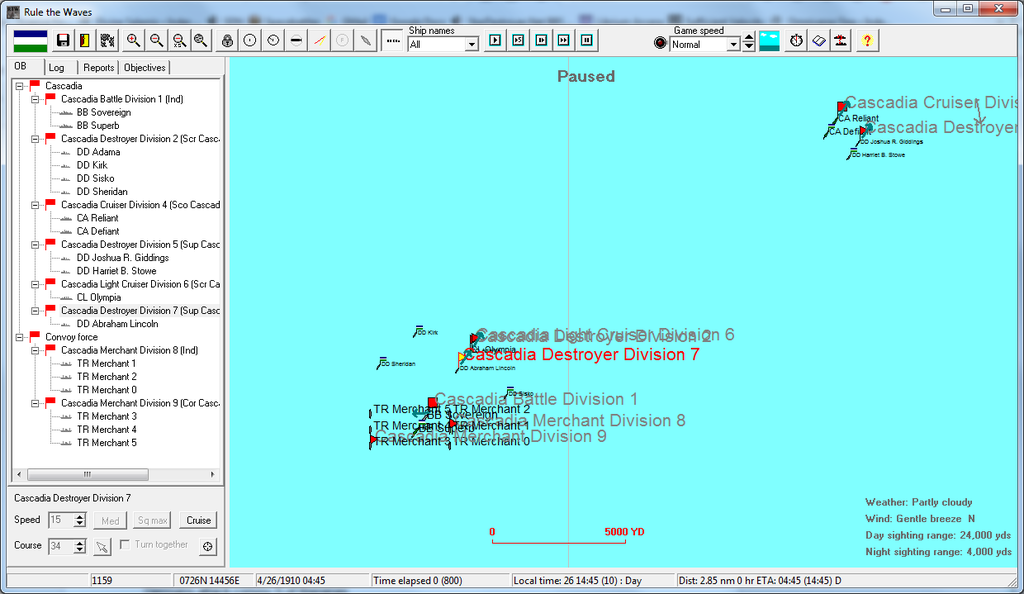

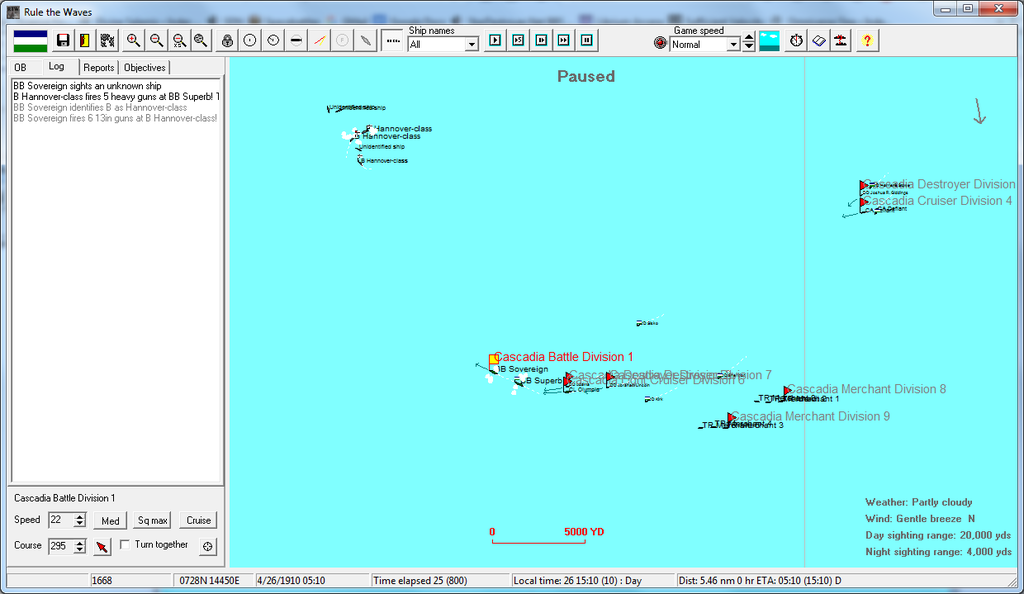

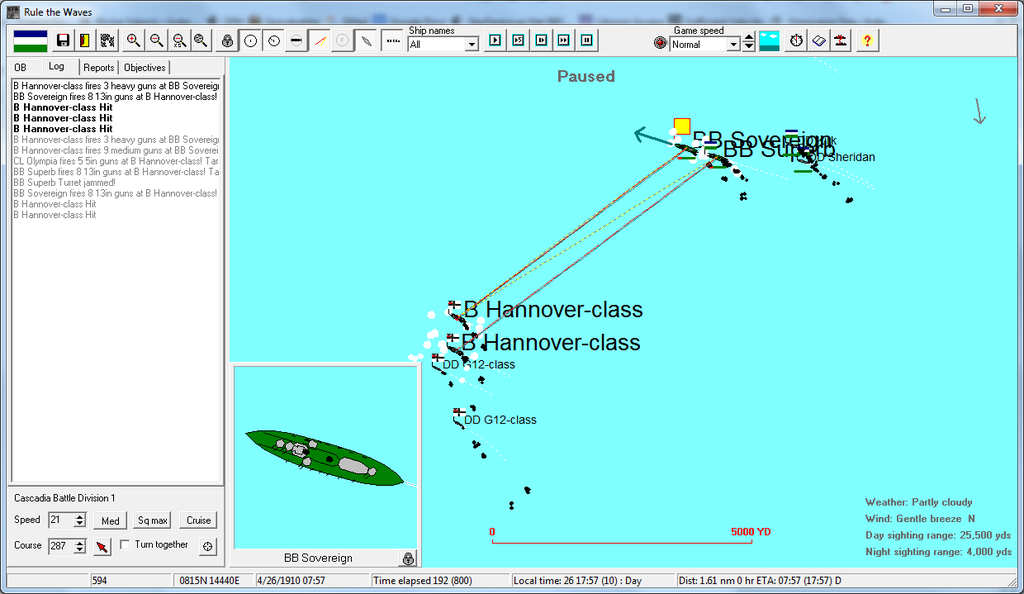

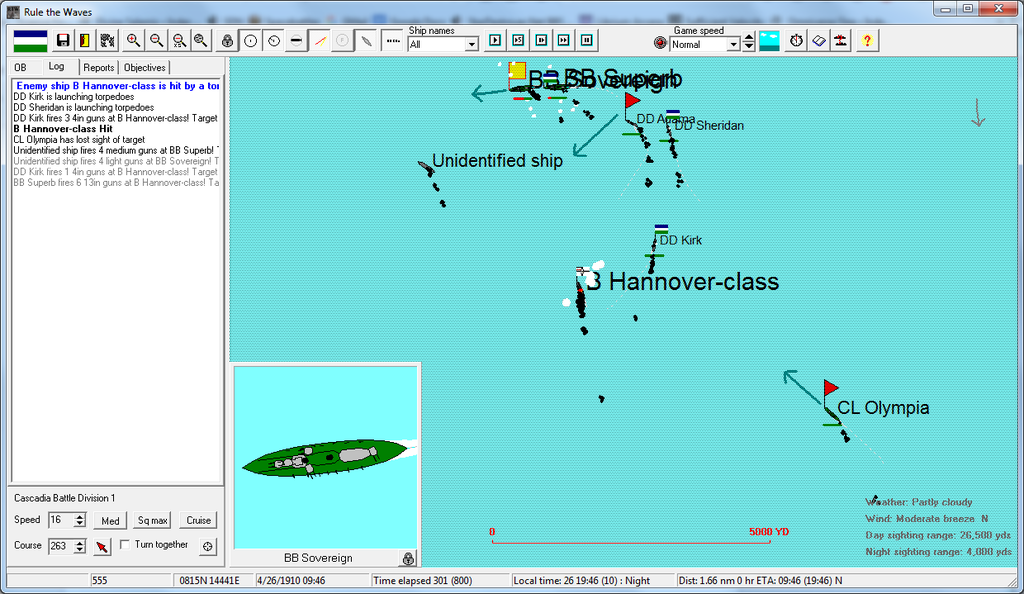

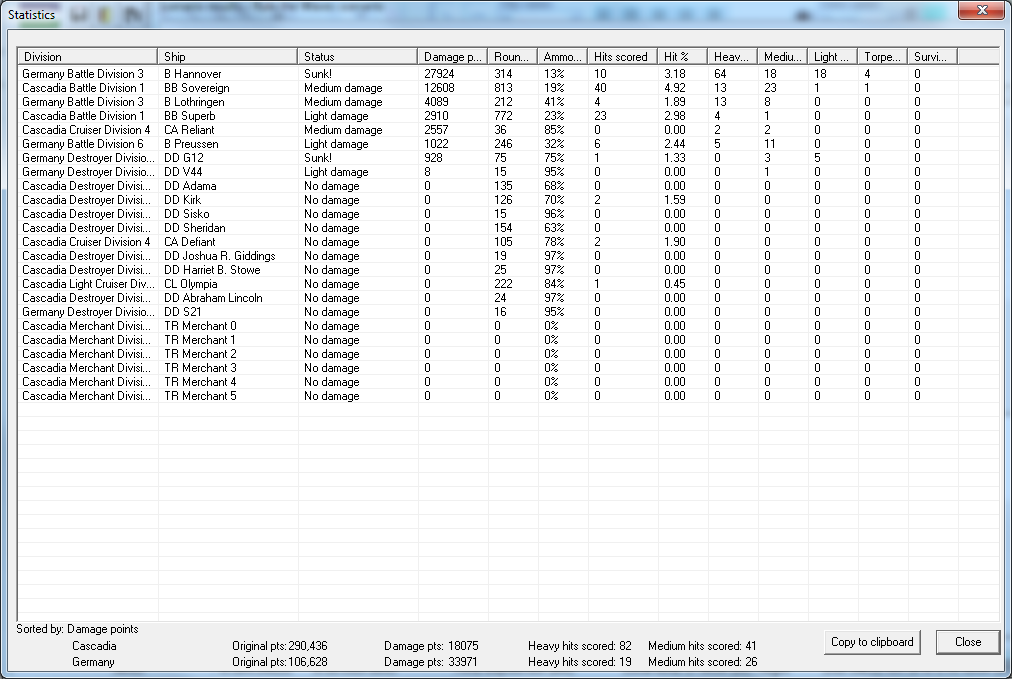

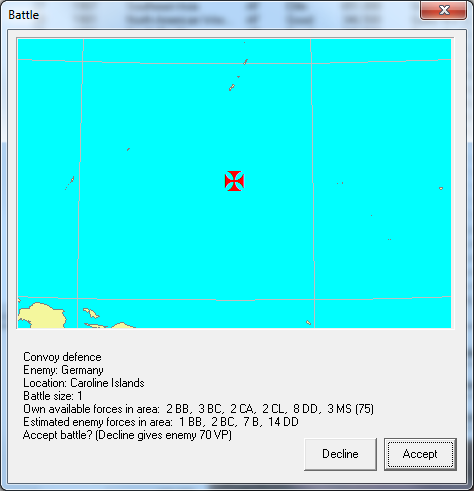

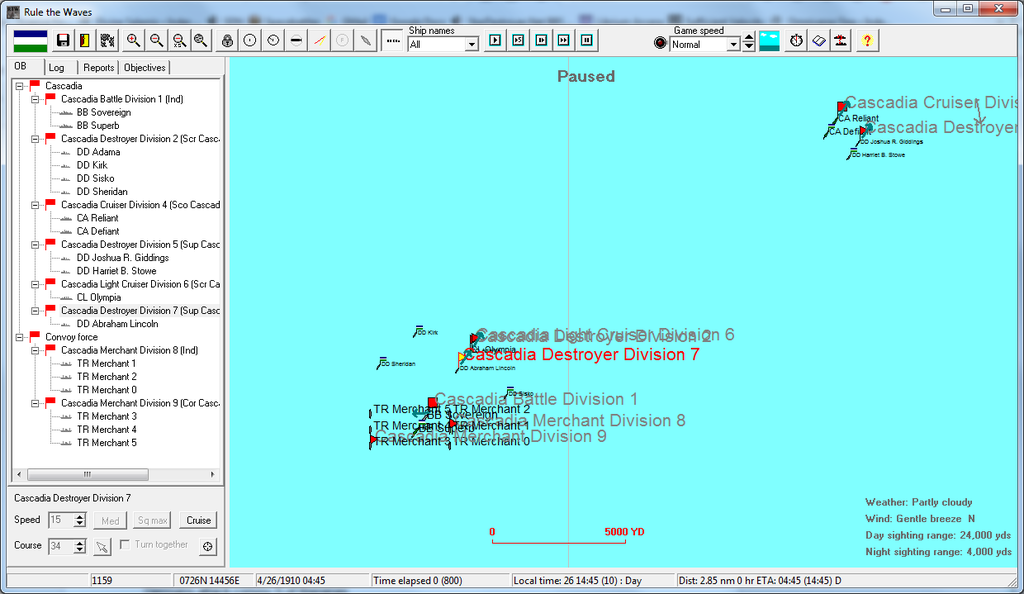

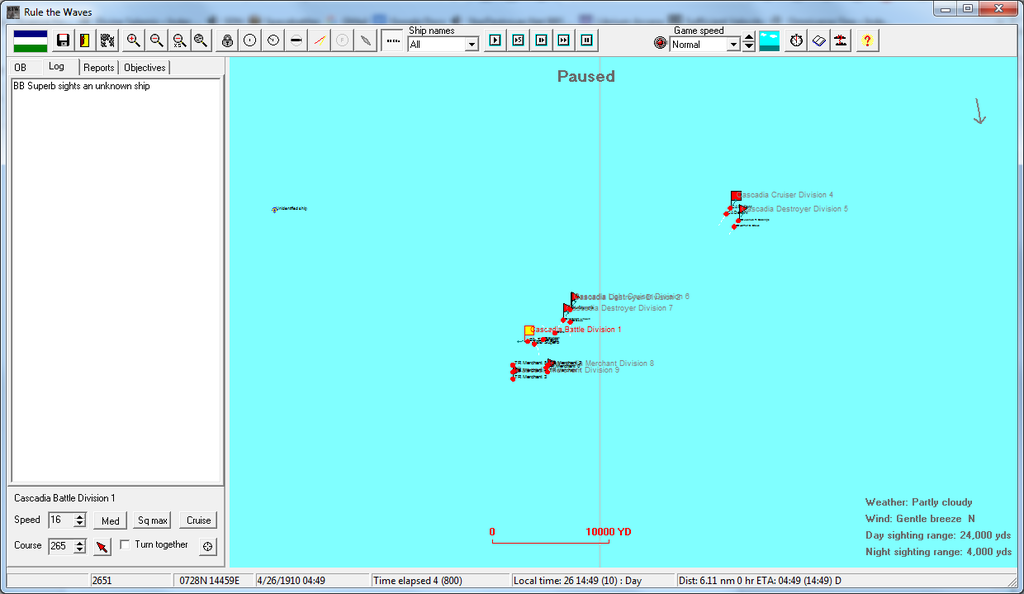

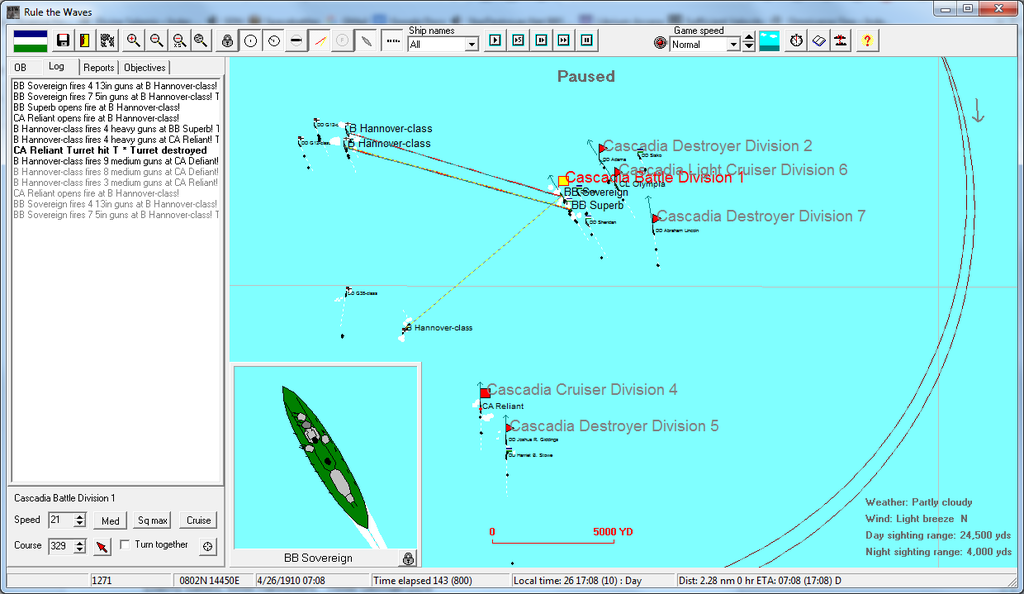

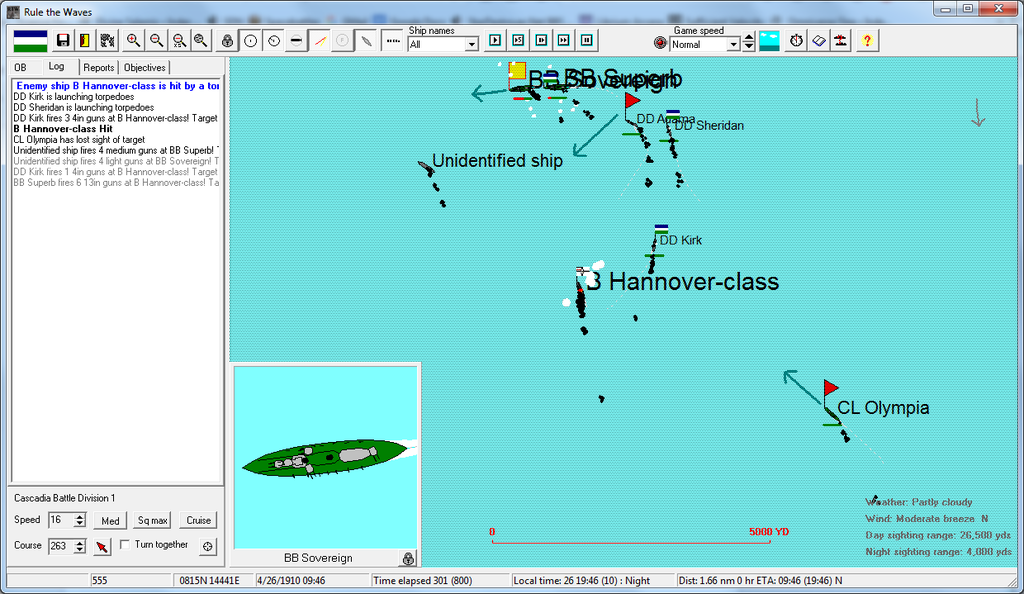

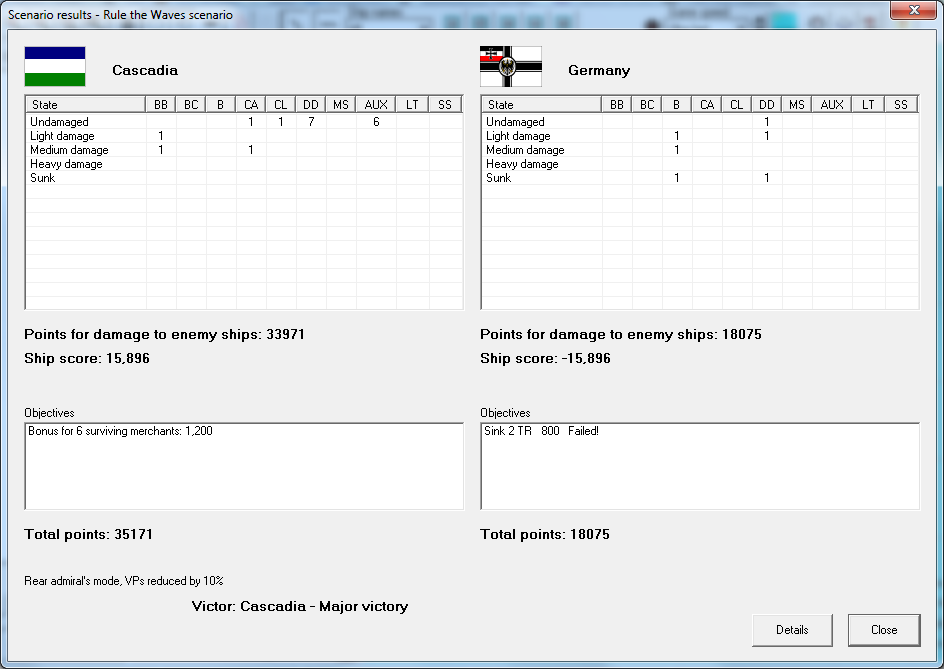

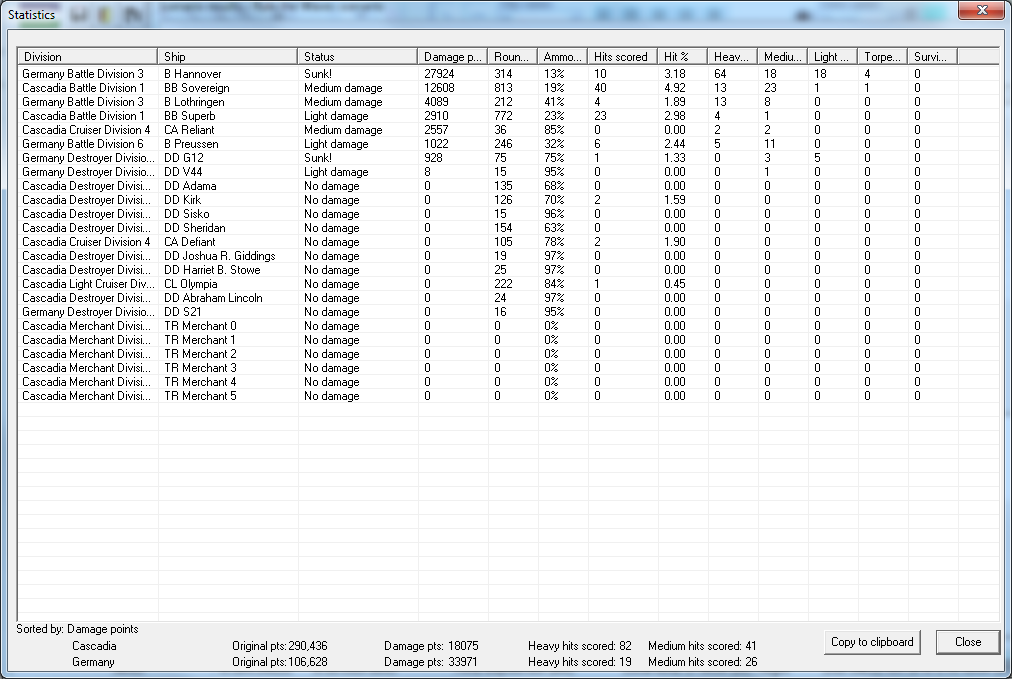

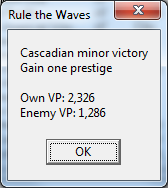

Meanwhile, in the Pacific, the Cascadian Navy was getting the day it had been waiting for. On April 26th Admiral MacCallister, flying his flag from the

Sovereign, was leading a significant force in escort of a transport convoy to the Philippines when the Germans offered battle with a battle squadron due south of Guam and west of Truk.

CRS Sovereign

CRS Sovereign

Caroline Islands

26 April 1910

Captain Reginald Etps looked through his binoculars at the lines of slow-moving merchantmen and transports beside his ship. The

Sovereign was steaming along to the west at a leisurely 10 knots with much of the East Asian Fleet.

Superb steamed on behind her. Four of the

Kirk-class destroyers were alongside them as screens while the protected cruiser

Olympia and the

Sherman-class destroyer

Abraham Lincoln were further to stern. And further back, in a vanguard scouting position, was Etps' old command

Reliant and the ship he had fought the Spanish aboard 12 years ago, the

Defiant.

Joshua Giddings and

Harriet Stowe were accompanying those cruisers as screens.

His XO, Commander Walter Pileggi, was looking out at the sea with his own set. "Do you think the Germans will intercept this time?"

"I suspect they are as impatient as we are, Commander," Etps replied. To think that he was at war with Germany again. There were nights he still remembered the 30th of July, 1903. The tension, the excitement, that feeling in his stomach when Commander Parker's position was hit by shell shrapnel, or when that German torpedo had hit the

Anchorage.

Now here he was, in the most coveted command of the Cascadian Navy, and that kind of tension was seeping into him again.

It was made worse by the growing discontent in the crew. For over a year the

Sovereign had been moored at Chuuk, in position to intercept German ships from either the Bismarcks or the Marianas, holding the vital Pacific anchorage and its connection to the Philippines. There was little to do in the islands of the lagoon and his men had grown frustration with the lack of opportunities on leave. The Navy was abuzz with the talk of Socialist agitators having been drafted into the crews, and that they were using this to spread dissent and anti-war sentiments. Some even insisted they intended to mutiny and seize the ships.

Etps thought that was far-fetched. But he was aware of the discontent. And it was starting to worry them.

Perhaps a battle with the Germans would…

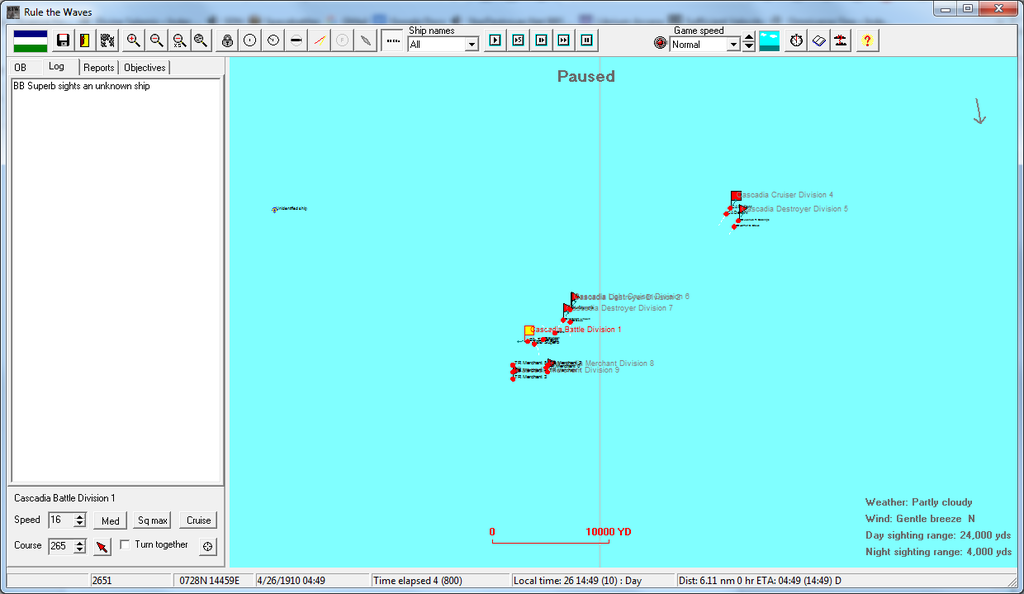

"

Sir!" A voice came over the tube coming down from the mast. "

Signal from Superb,

sir! Enemy spotted to the northwest!"

Etps exchanged a look with Pileggi. "XO, inform Admiral MacCallister. All hands to general quarters! Action stations!"

The deck officer sounded the ship-wide alarm. Across the vessel the crew of over a thousand rushed to their action stations.

"Helm, make bearing two-eight-five, ahead to flank speed," Etps ordered.

"Aye sir, helm bearing two-eight-five. Signaling engineering for flank speed."

The

Superb's signal had gotten through to the other ships by this point. All began to maneuver to engage the unseen enemy. Etps moved his binoculars in that direction until he spotted the coal-smoke far on the horizon. Multiple enemy ships… and what he suspected were at least three enemy battleships.

Admiral MacCallister made his way on the bridge, to the whistle of a waiting bosun. All, including Etps, stood at attention and saluted. "At ease, gentlemen," MacCallister answered. He took up his own binoculars and looked out the window at the distance. "Looks like the Germans are finally ready for a fight. I'm guessin' they thought we wouldn't assign the battle line to escort this convoy."

"I've taken the liberty of putting us on an intercept course, sir," Etps said.

"Good. Good show with that, Captain. Make ready for the engagement. Signal the

Defiant, I want the cruisers on our south should the enemy have faster ships coming up. Let's see what the Germans have sent us..."

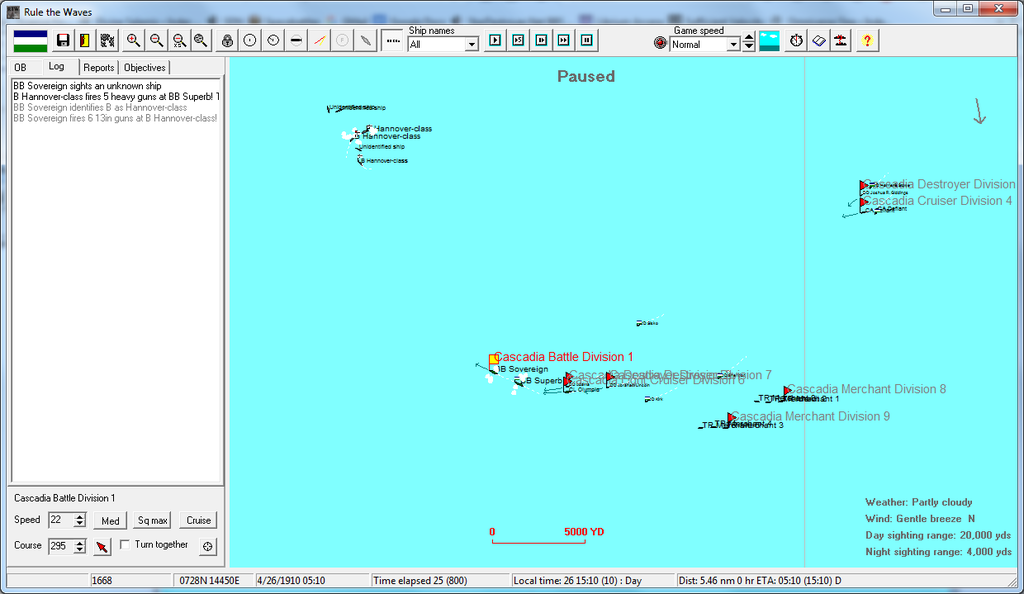

The German battleships in question were the

Hannover,

Lothringen, and

Preussen. When the commanding admiral of the German division spotted

Sovereign and

Superb, he realized the extent of his miscalculation. He ordered his fleet to break off to the north.

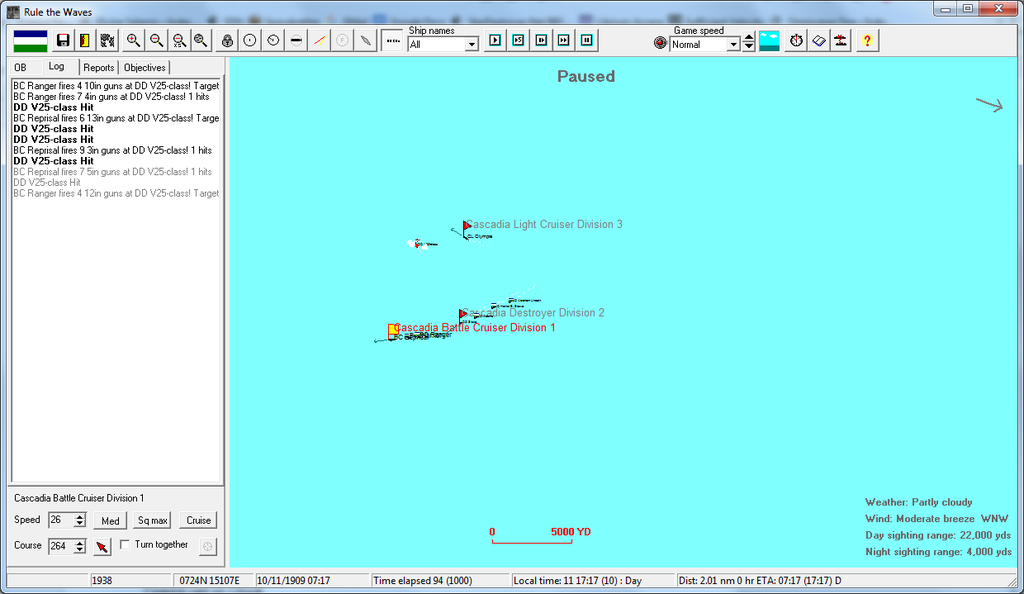

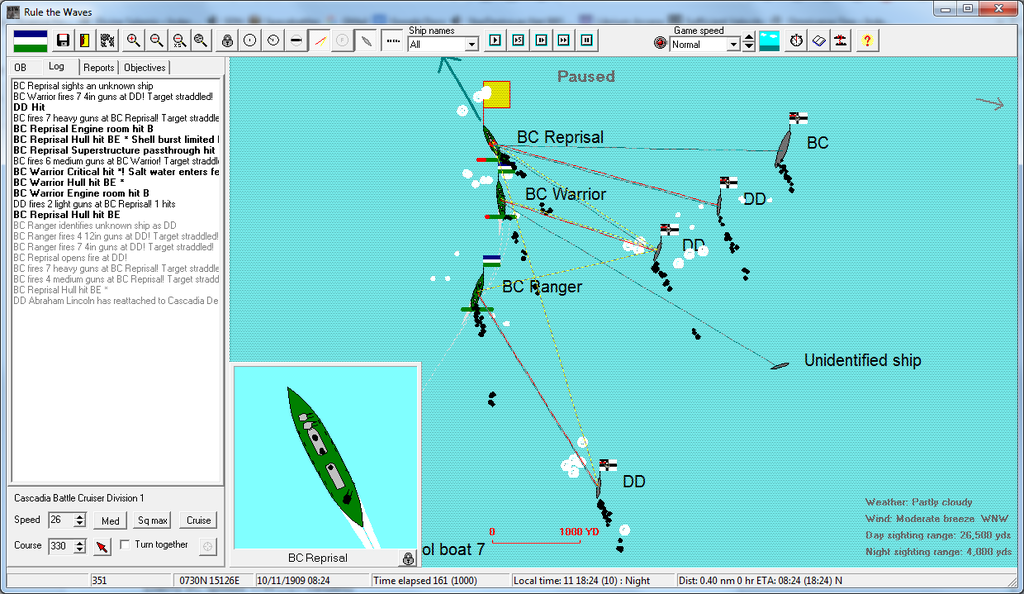

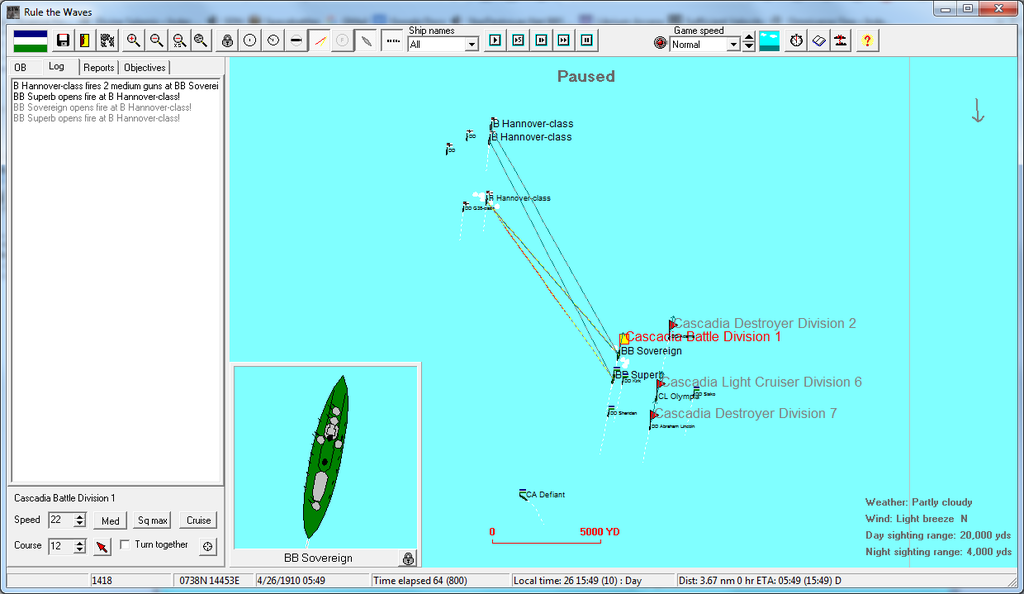

But the German ships could only make 19 knots, at best. The superior speed of the big Cascadian ships allowed them to close the distance and begin firing on the Germans.

The main advantage for the Germans was Admiral MacCallister's fear of their torpedoes. He kept the ships at long range, over 15,000 yards, to avoid getting the pride of the Cascadian fleet torpedoed this far out from Chuuk. The long range, however, meant that accuracy suffered.

CRS Superb

CRS Superb

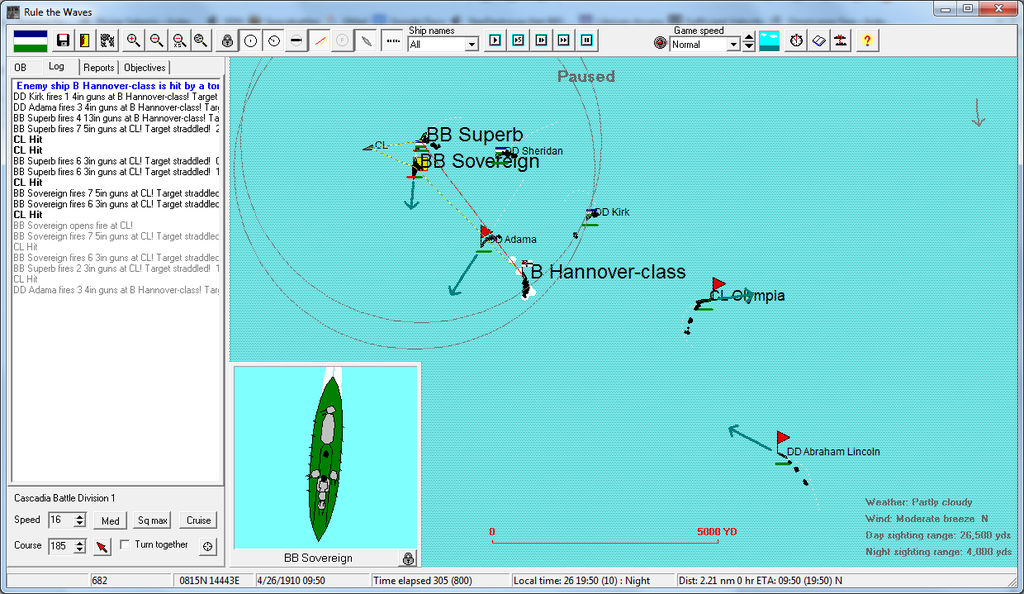

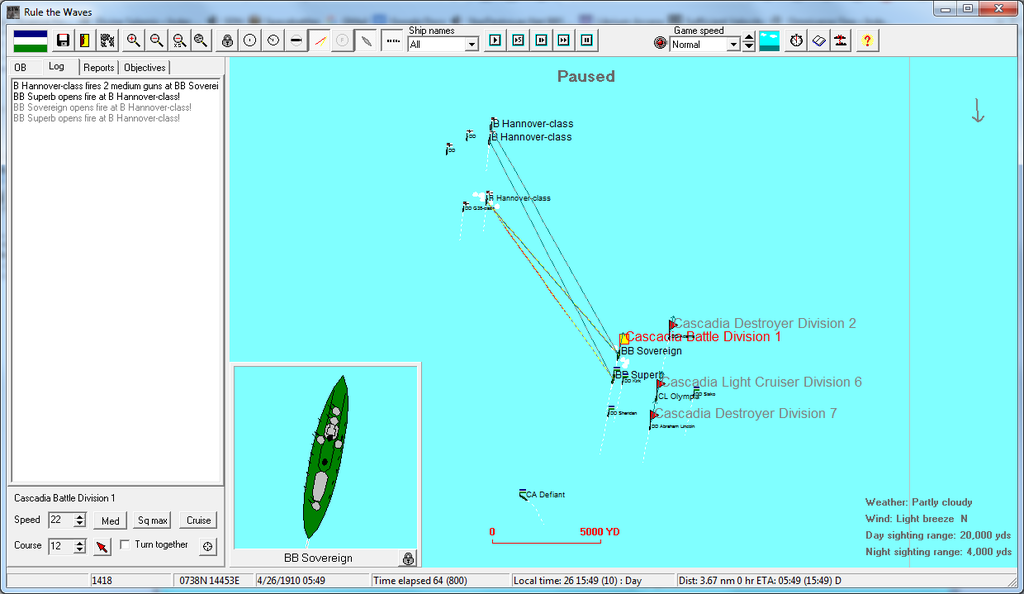

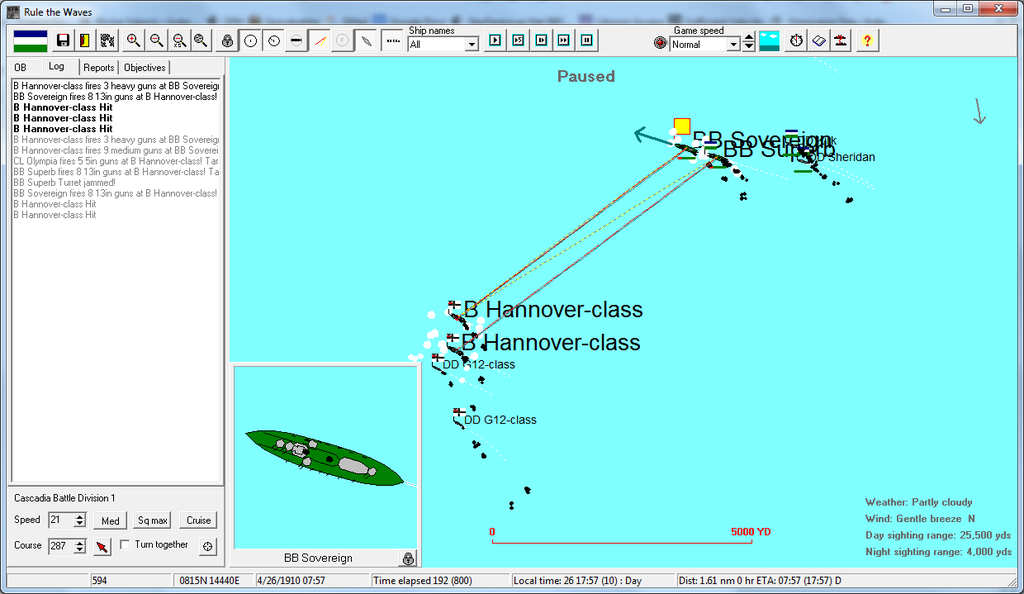

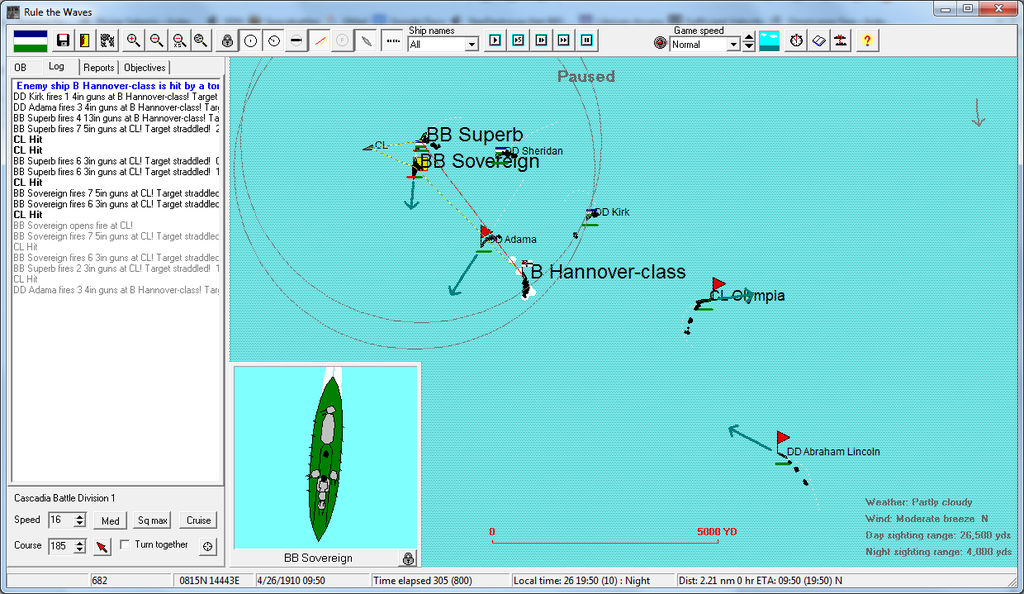

Captain Wallace felt like grounding his teeth. Almost two hours of firing, but at this ranges his gunnery officers had their work cut out for them. He glanced at Pentworth and mumbled, "We should get closer. Draw within 10,000 yards, at least."

"I agree, sir. But the formation is not doing so."

"Curse the man. This is the day we have been waiting for. Three damn German battleships, but we outgun them two to one." He looked nervously at the time. It was spring, so the days were getting longer, but they would end up in darkness within a few ours.

He put his binoculars up to his face again. To the west the German battleships continued to steam for safety. The Germans were firing for all they were worth, knowing their one hope was to cripple their faster pursuers.

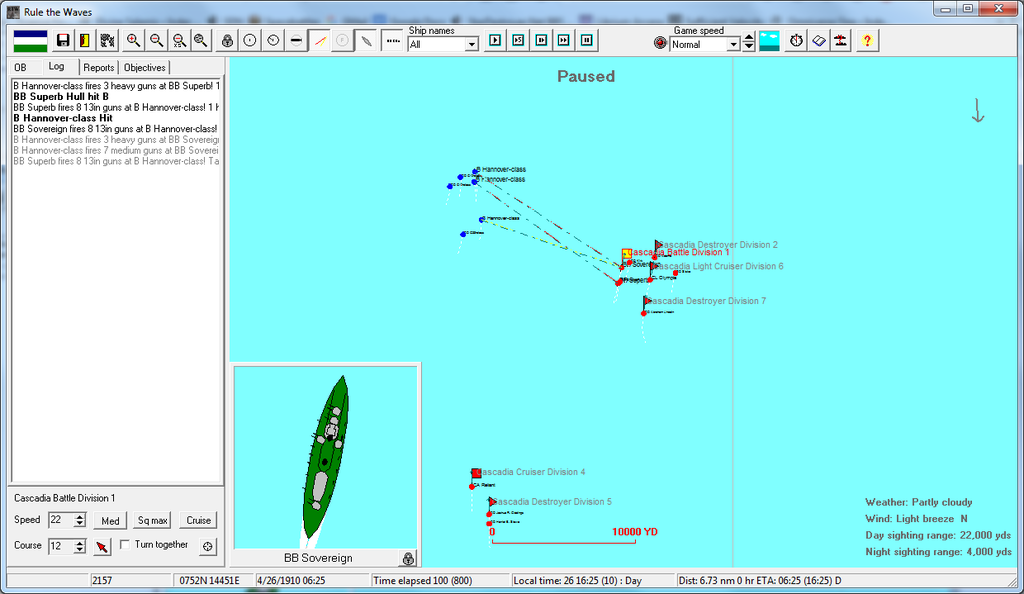

And then there was a blast in the distance. Wallace saw his ship's target take the direct hit and smiled to himself. "Well done." Now if they could only land more hits to finish these Germans off…

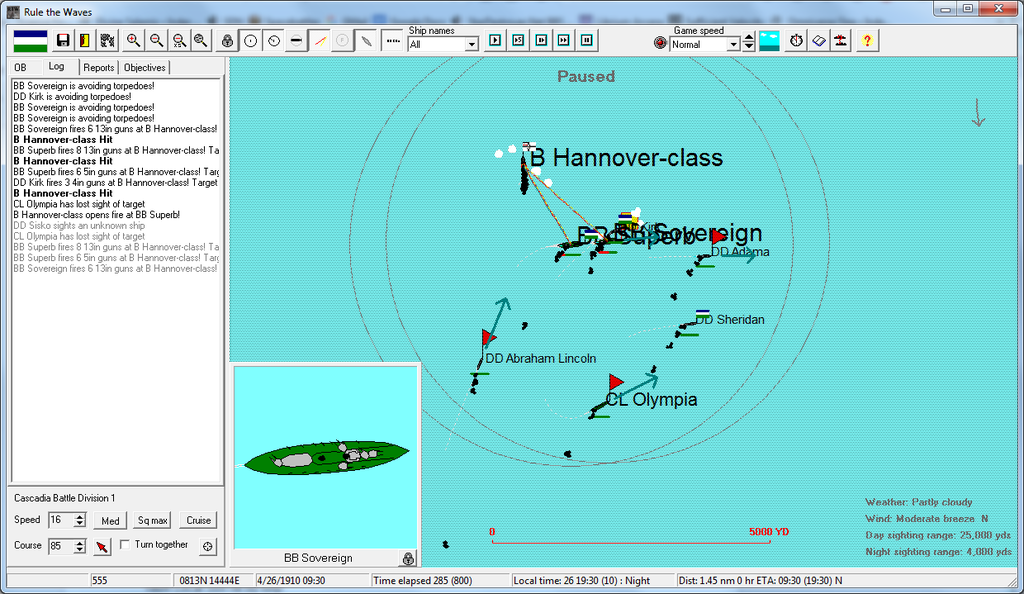

As night drew closer, Admiral MacCallister finally gave the order. The battleships began to turn more northwesterly, reducing the range to the German line. For the short term it was a slight disadvantage. The turn of the German ships meant that the angle to close the distance required bringing the Y turret out of arc, reducing the guns firing on the Germans by two per ship.

One German ship, with engine trouble, fell out of the line partially. It was set on by the armored cruisers that were following the battle line, ready to cut off enemy attempts to turn south. In the exchange of fire the

Reliant lost a turret.

Meanwhile the Cascadian warships drew closer. The secondary batteries on the two ships began to engage as well. Shellfire inflicted damage on each side, but the Germans had the disadvantage that the Cascadian ships' armor was capable of repelling their shots, but the larger Cascadian guns were more effective against their own older armor schemes.

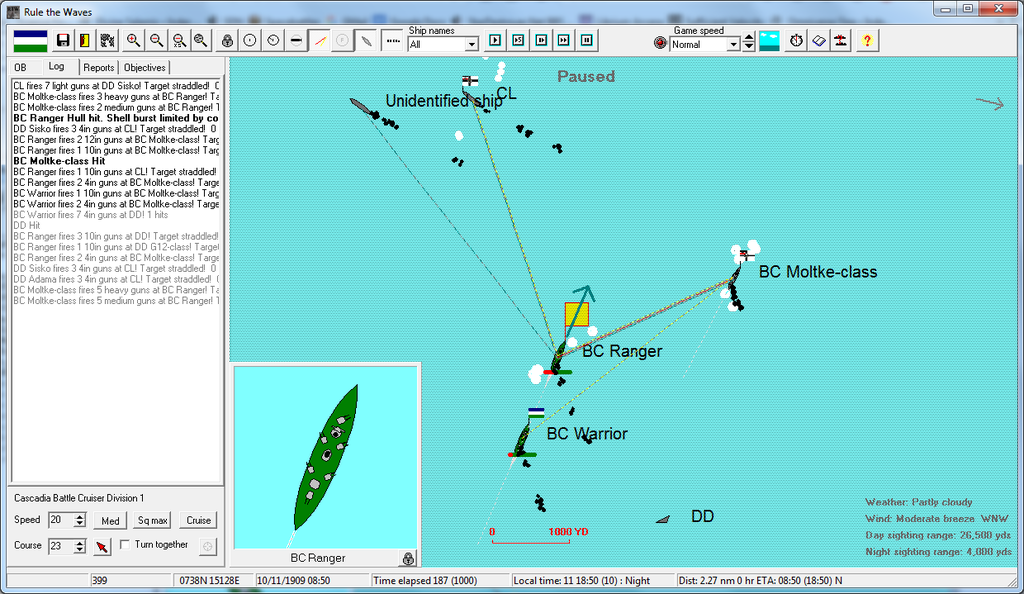

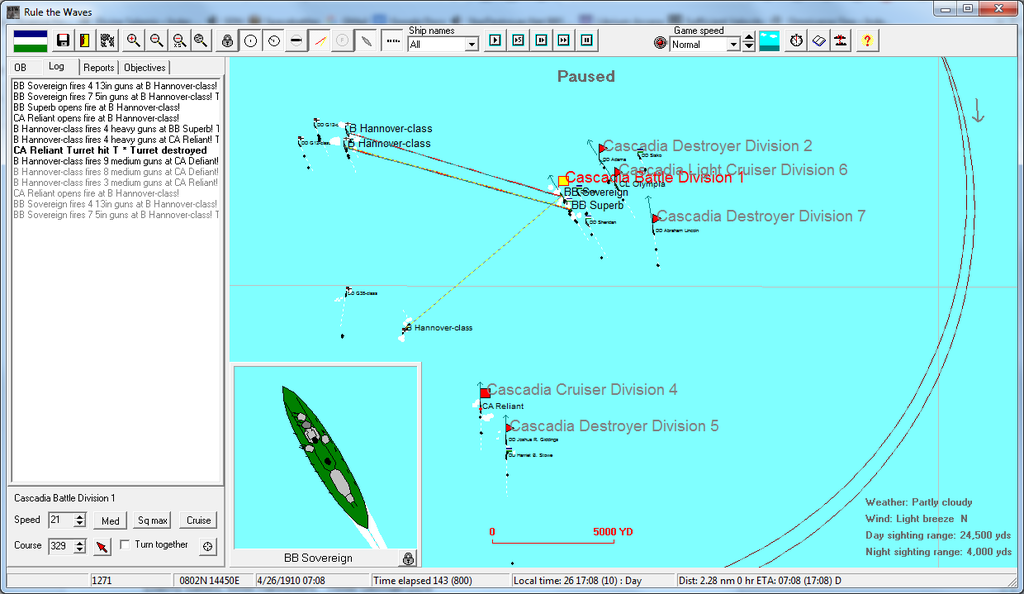

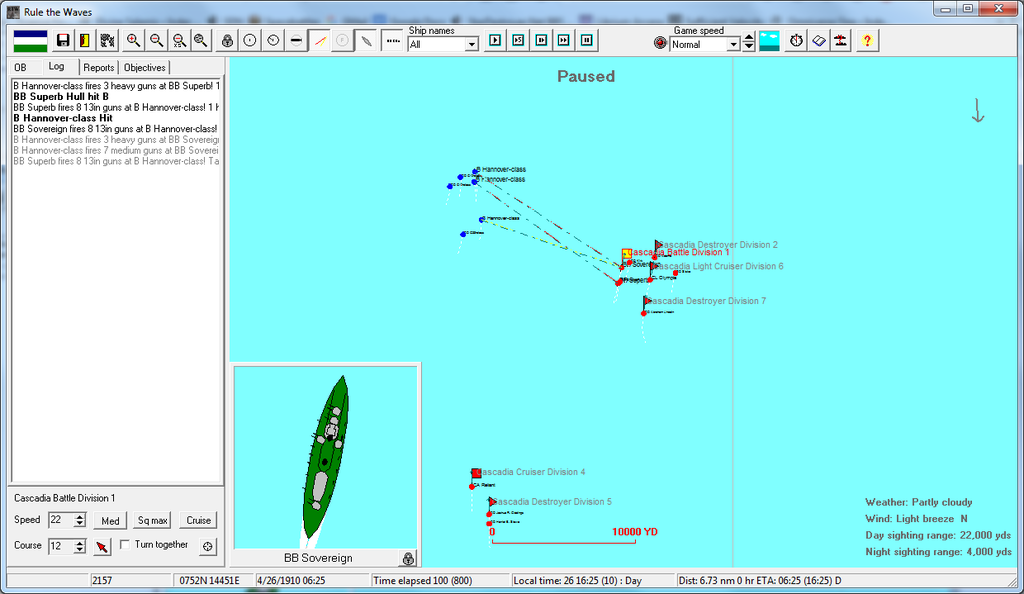

The German battleship

Hannover took repeated hits in her exchanges with the

Sovereign that progressively wrecked her.

The superior speed of the Cascadian ships soon brouught them north of the Germans. MacCallister ordered a turn to port. The Germans had to match to avoid getting their T crossed.

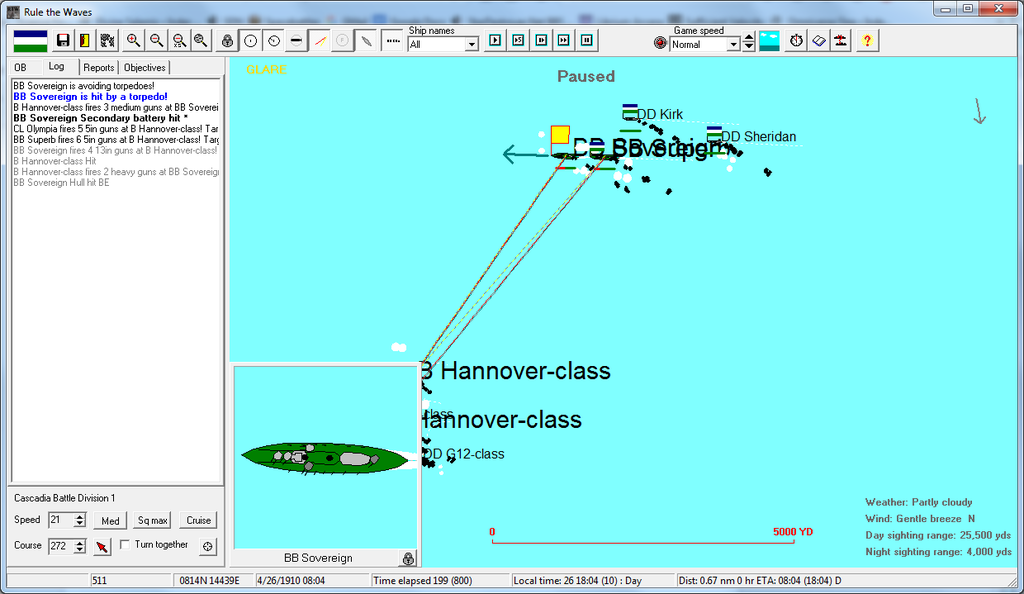

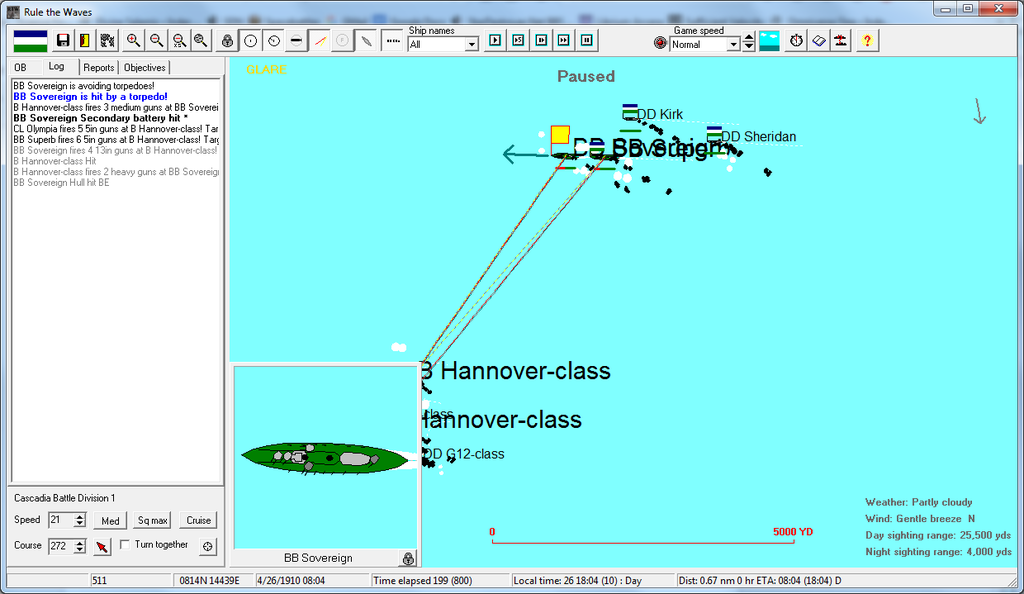

And then

Lothringen got lucky.

CRS Sovereign

Etps was watching the fight when he noticed a familiar disturbance in the water. "Hard to port!", he shouted. "Torpedo!"

The

Sovereign made a partial turn to evade the torpedo hit.

But it was too late.

For the second time in his career, Etps felt his ship shudder from a torpedo hitting it below the waterline.

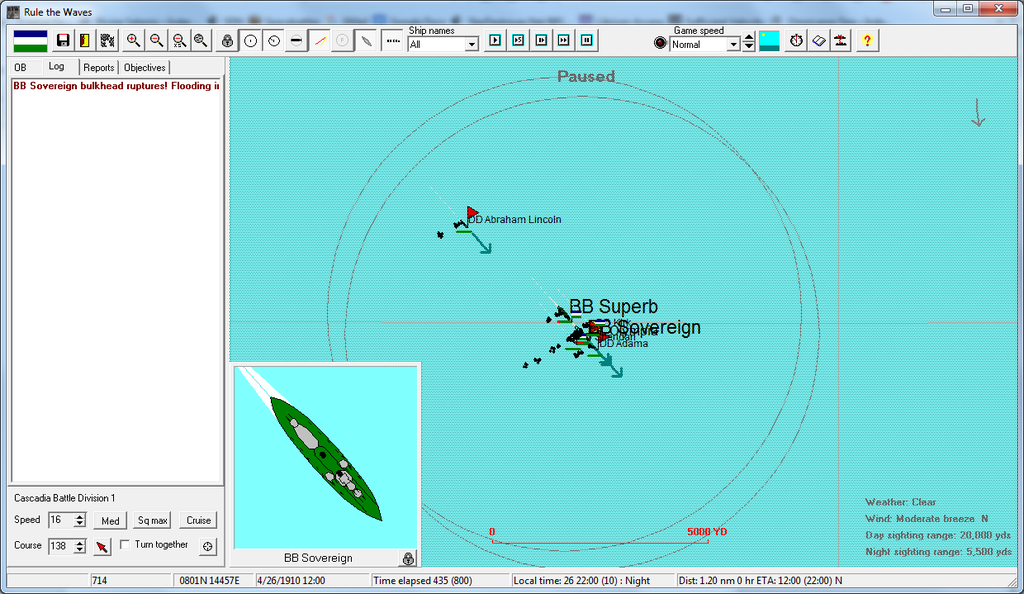

But this was different. The

Anchorage had been an old protected cruiser, and just one torpedo hit had threatened to sink her. The lessons learned from that had gone into the design of the

Sovereign and other ships to come since. The torpedo did not do nearly as much damage. Enough to cause some flooding, but not so bad as to force him to drop all speed or break off.

The 13" guns on the

Sovereign thundered again as the battle drew on. WIthin ten minutes, he had Lieutenant Paul Lockley on the bridge. The ship's senior Damage Control Officer was shaking his head. "We've tried to lock down the flooding, but the ship's speed is costing us work and time. We've got to slow!"

Admiral MacCallister overheard the remark while examining the battle. He sighed and nodded. "Signal to

Superb that we are slowing to halt flooding. Hopefully we will not lose the Germans for this."

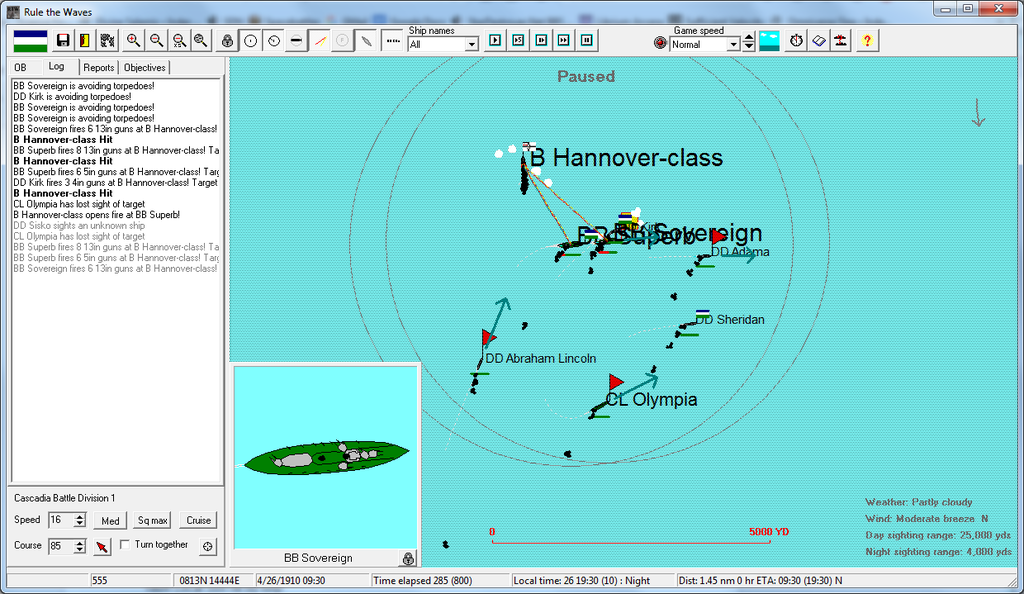

Over the course of the next hour, MacCallister's hopes were dashed. The need to slow

Sovereign and the onset of night allowed the

Lothringen and

Preussen to flee north, albeit with varying levels of damage.

Hannover, however, was too wounded to keep up. Even as night fell the two battleships began to pound away at her until she stopped. An hour and a half after taking the torpedo,

Sovereign even returned the favor with her own.

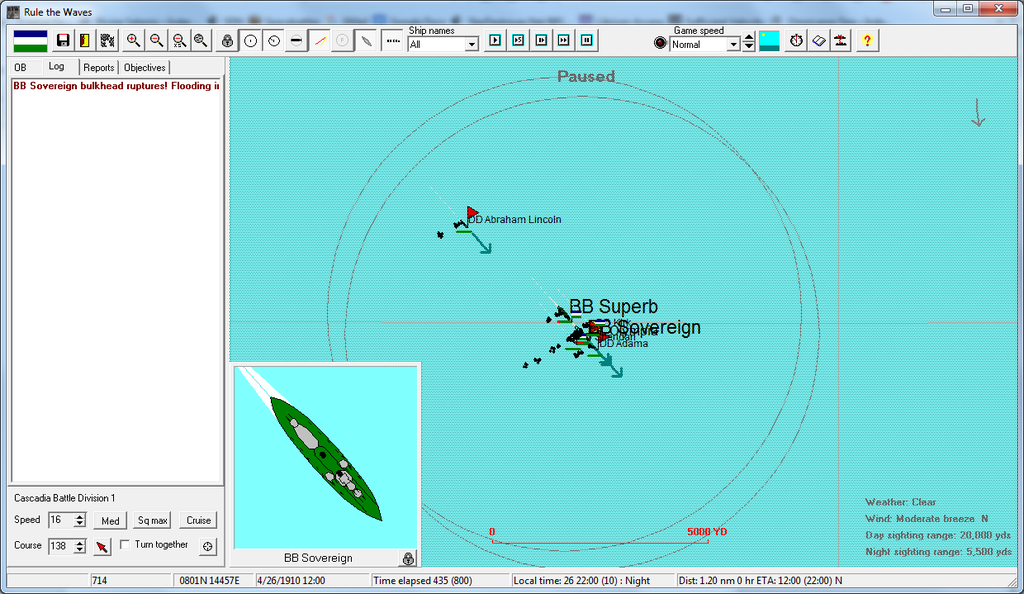

Under fire, torpedoed, the

Hannover was already sinking, but it was not immediately evident to the Cascadian ships, who continued to fire upon her. When another form came out of the darkness and was identified as a German ship, the

Sovereign fired guns into her until she was a burning wreck.

Soon it was clear

Hannover was slipping beneath the waves. Survivors were picked up as possible and the entire force broke off to meet up again with the transports.

During the trip back, one of

Sovereign's bulkheads ruptured, flooding another compartment. The ship and fleet had to slow to eight knots for ten minutes until damage teams had dealt with the situation. They rejoined the transport convoy some time later.

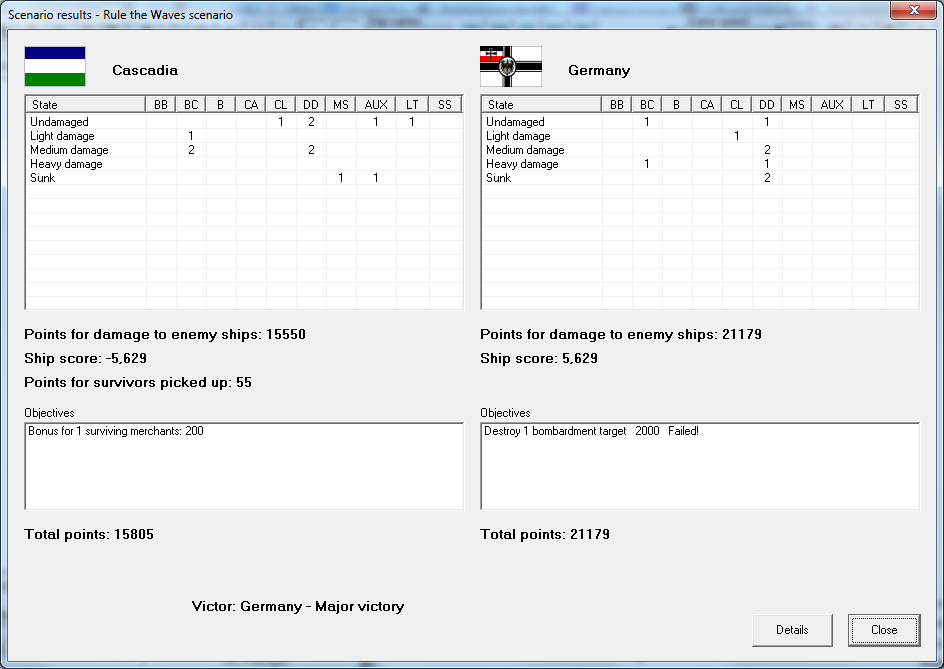

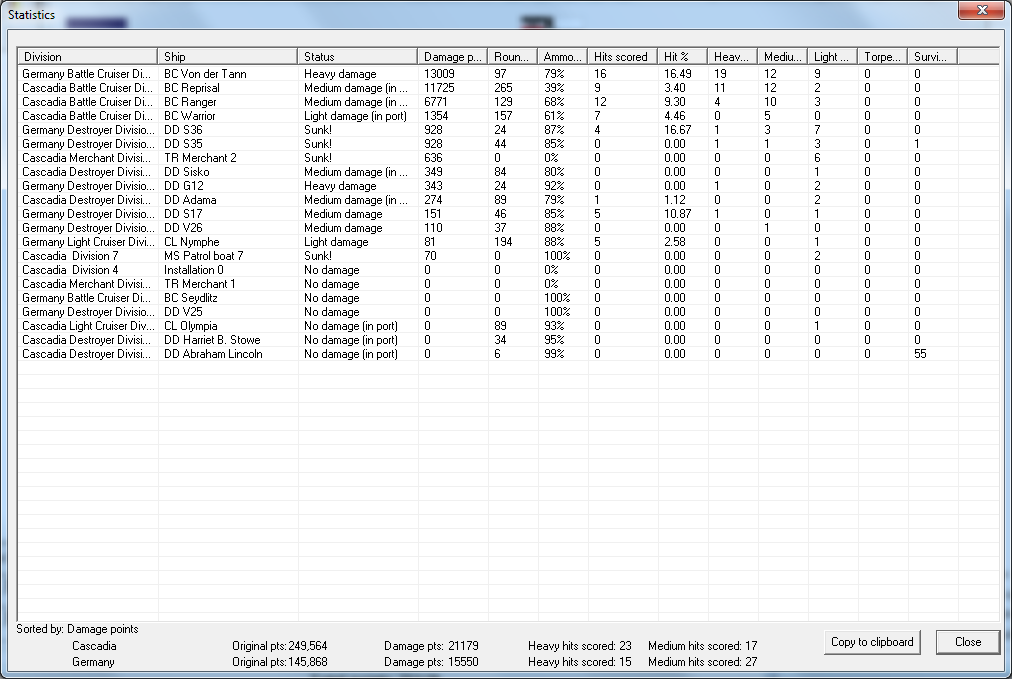

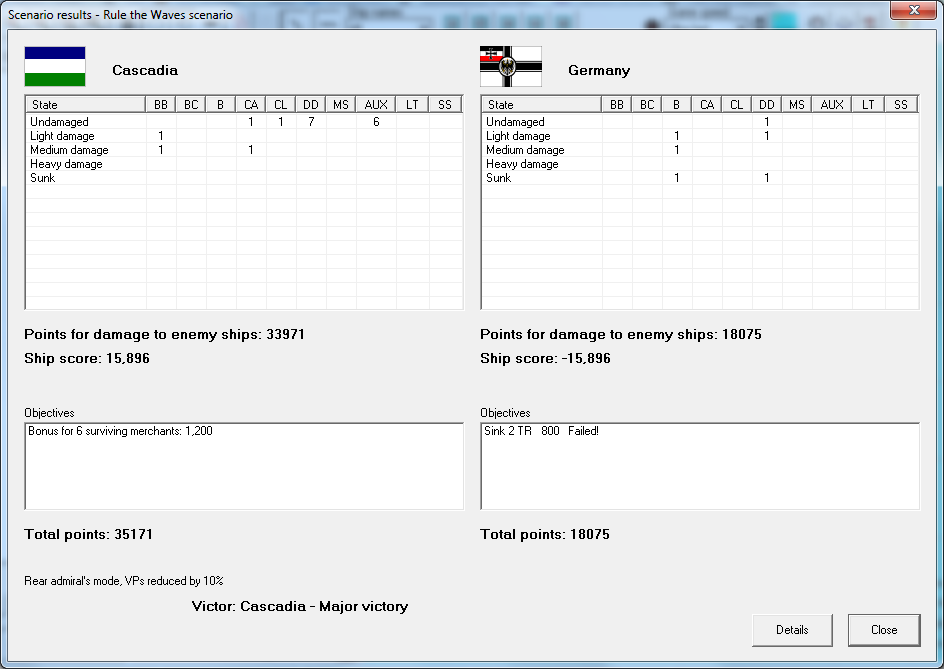

The battle was the one time that Cascadian and German battleships faced each other in the war. It was not a stellar day for either side. The Germans walked away with the greater loss, losing

Hannover and a G12 destroyer. But the engagement was hardly the unqualified succcess that the Cascadian Navy had hoped for. MacCallister's belated decision to close the range cost the fleet critical time in putting crippling damage into all of the enemy ships. The failure to reduce the German fleet significantly ruined Cascadia's last chance to make any attacks to seize the Bismarcks or Marianas.

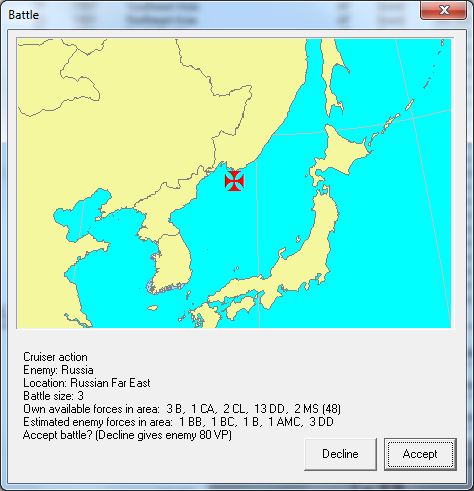

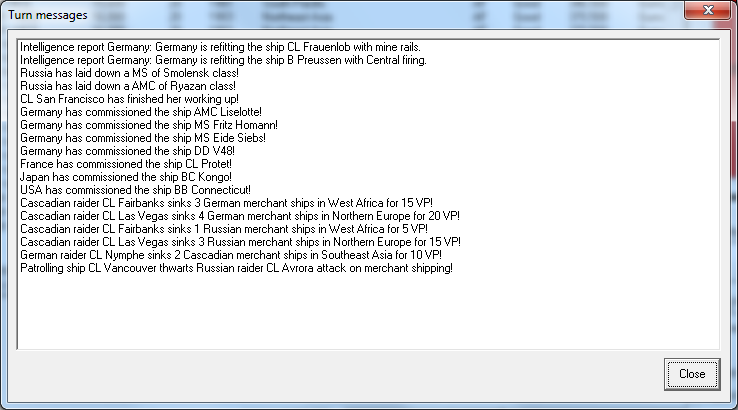

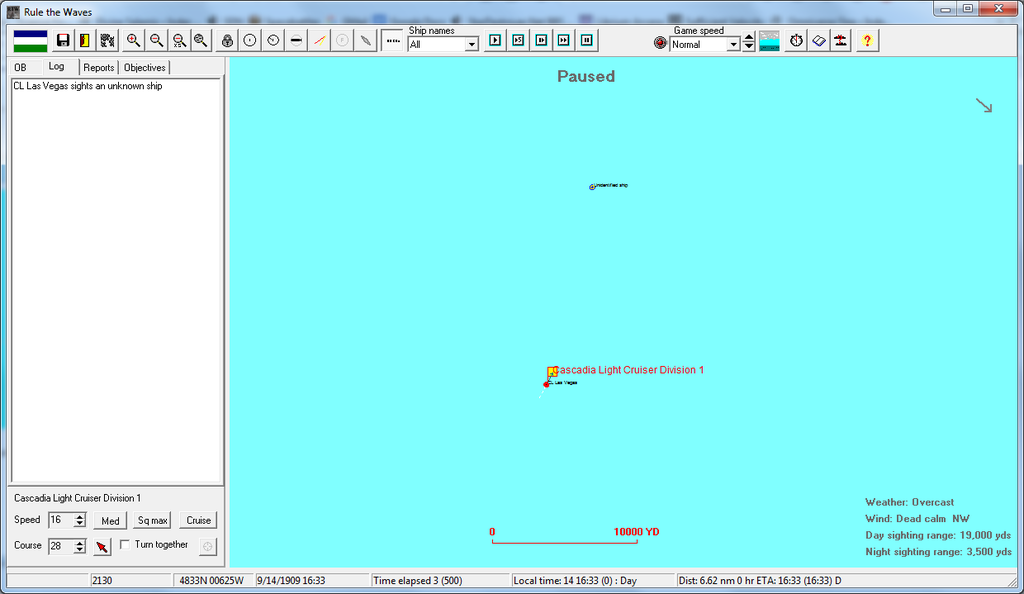

The month of April was a bad month for Russo-German raiding cruisers. They were repeatedly foiled in multiple areas of the globe.

Admiral Garrett orders the laying of the final

Constitution-class battleship, the

Independence.

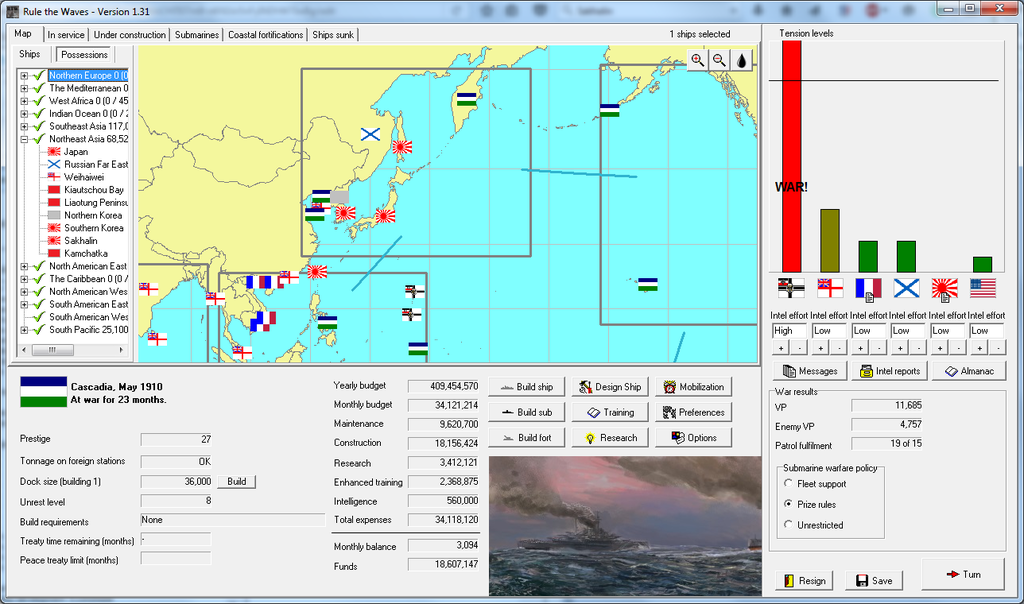

May 1910

The French follow-up offensive, ill-considered as it was, launched on time. The French armies, supported to one flank by elements of the Cascadian 1st Army and on the other by the Japanese 6th Army, struck the Russian forces between Metz and the Luxembourg border. As expected, the Russian morale was so low that they broke and fled. By the end of the second day the Russian trenches were in French hands.

French aeroplane scouts had spotted the German lines by this point. But the French command was certain the German troops were massed elsewhere due to careful movements by the German command. When they charged at what they assumed to be the Russian reserves, the Germans opened up on them. The result was another gruesome slaughter as the French and Allied forces were mowed down. The Cascadian and Japanese forces fared little better. The 2nd Guards Regiment, which had won acclaim for its defensive stands, suffered terrible losses when ordered to lead an attack through no man's land, such that the crack regiment was pulled from the line with just six hundred combat effective men left.

Through May 10th the French command ordered repeated assaults, but whatever gains they managed the Germans would reclaim with quick, vicious counter-attacks. Finally Joffre, forced to recognize what was going on, ordered a halt to the attacks. Another hundred thousand men were casualties. The Cascadians and Japanese forces had suffered proportionately as well. Cascadian combat casualties over the prior two months had surpassed two hundred thousand.

But the planned German counter-stroke never materialized. The Germans needed their troops for other duties, as it turned out.

Because on May 11th, the Russian Imperial train had rumbled across the Baltic border into East Prussia.

Tsar Nicholas II had been overthrown.

On May 1st the end began. After over a month of quiet the great industrial cities of Russia exploded in a wave of discontent and dissent. Workers across the country declared a General Strike. Dissident lawyer Aleksandr Kerensky addressed a workers' gathering on the morning of the 1st, declaring that the country needed "Peace, land, and bread!" to rapturous cheers. Not to be outdone, Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin had been smuggled into the country via Norway and Finland by French agents, and he declared the need for revolution to the assembled masses.

The time would come when the two men struggled for the soul of Russia. For now, they worked together in fomenting the General Strike and organizing to protect working class districts from government reprisal. Government police forces and the armed troops still in the city did move in, but workers armed by the various leftist parties drove them off. By the end of May 1st, the Russian government felt compelled to call in more troops.

On May 2nd the situation continued to be chaotic. The first troops that arrived were deemed insufficient to restore control over the capital. Word arrived that troops stationed in the interior were struggling to make their way over sabotaged railways, with rail workers openly trying to turn the soldiers against the government. Fighting broke out at several locales between armed leftist radicals and the troops.

Finally on May 4th, after three days of chaos, the Russian military arrived in sufficient force to retake St. Petersburg. The crowds of workers were ordered dispelled and were fired upon when they failed. Fighting broke out in several quarters before the radical leaders urged their followers to hide away and preserve themselves for another day. They had, perhaps, planned to let the occupation of the city fester for a few weeks before proceeding. Meanwhile factory managers were given lists of arrested workers to fire and granted detachments of soldiers to provide an armed watch over their sullen workforces.

However, on May 6th, another demonstration gathered. This one, in contrast to the worker marches, was peaceful. It was made up disproportionately of women, children, and the elderly. Many carried photographs of the Tsar and his family and religious iconography, praying to the father of their country to ease their suffering. The rise in food prices and the inflation were crushing them.

Despite the clear nature of the protest, Russian military commanders were skittish. The demonstrators were ordered to disperse. When they failed to do so immediately, some of the troops opened fire. Screams and cries went up among the unarmed demonstrators, who fled in a panic.

More troops arrived, with orders to pin the demonstrators in and fire until they surrendered. But upon seeing the crowds and the dead innocents, the soldiers became enraged with their commanders. All of their anger and feelings about the war, their discontent, simply boiled over. Instead of taking the demonstrators, they started shooting their own officers and the troops that had fired on the unarmed civilians.

The soldier mutiny quickly spread. When word of what had happened came to Kronstadt, the Russian fleet was crippled by mutinies. Other soldiers rushed to join the rebellion that had now erupted in the army. Officers either joined out of self-defense or were shot pre-emptively by their troops, with some managing to escape.

Kerensky and Lenin, among the other leaders, brought their followers back out into the street. The Russian government was utterly paralyzed by the sudden union of soldiers and workers in revolt.

The news went out over wires that night. On May 7th, the isolated government, hiding in the palace, were informed that other troops called in were not coming. The massacre had prompted an open army revolt. Army soldiers and industrial workers across the country were joining to overthrow the Tsarist government.

Seeing the inevitable, Sergei Witte, as the Tsar's current chief minister, sent out a note on the 9th asking for what terms the rebels had. What did they want the government to do? The reply was immediate: Make peace. End the war. And for the Tsar, Lenin wanted him arrested, Kerensky wanted to make him a constitutional monarch with severely limited powers, and the two and other leaders compromised on exile. Lenin secretly gave orders for Bolsheviks in the railways to sabotage their car and kill them, however. That this did not happen is believed to be from the order failing to percolate through in time before the Romanovs left.

On May 10th, many gathered at Tsarskoe Selo to watch as the Romanov family departed by unmarked carriage. They made their way to their train where, under protection from loyal personal guards, they fled to exile in Germany.

The news of the collapse of the Russian government changed the entire dynamic on the Western Front. Von Moltke could no longer afford an offensive, not when he had to get the Russian troops out of the country before their revolutionary fervor polluted his own. To the chagrin of Berlin, the Army took the step of using every available train to get the Russian army out while new German units took their place in the line. The operation was completed with superb skill and speed by the German military, but it still took weeks to manage the replacement of Russians with new German units.

The French had literally attacked too early. Had they waited, as Joffre and others requested, the offensive might have come down during the transition and broken the German lines utterly. As it was, the Allied troops were too bloodied and tired to take advantage of the situation. A sort of partial truce fell over the Western Front, punctuated by night-time raids across no man's land and the occasional shelling. For the moment, neither side wanted to attack.

Meanwhile the new Russian Soviets met to assemble a government. It would be broadly Socialist in makeup, with land redistribution and worker control and ownership of factories. Military commands would be overseen by officers elected by the soldiers and sailors.

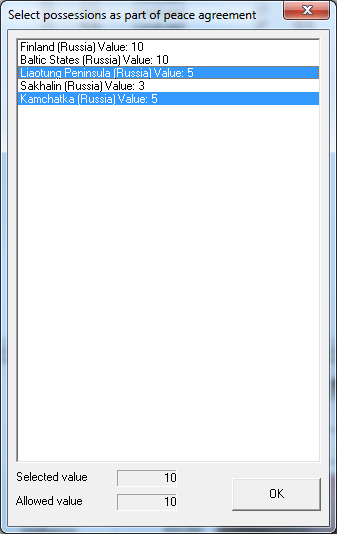

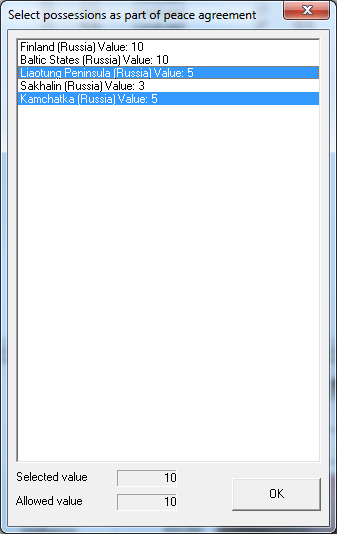

But just as important as setting up their new government was getting peace made with the Allies. Both leaders hoped that the Allies would be generous in victory. They were willing to abandon Russian pretensions to Manchuria, but anything else would be too much. But Lakeland and his Japanese counterparts had other ideas.

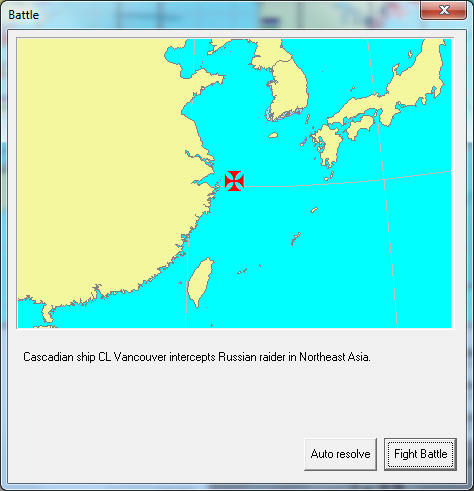

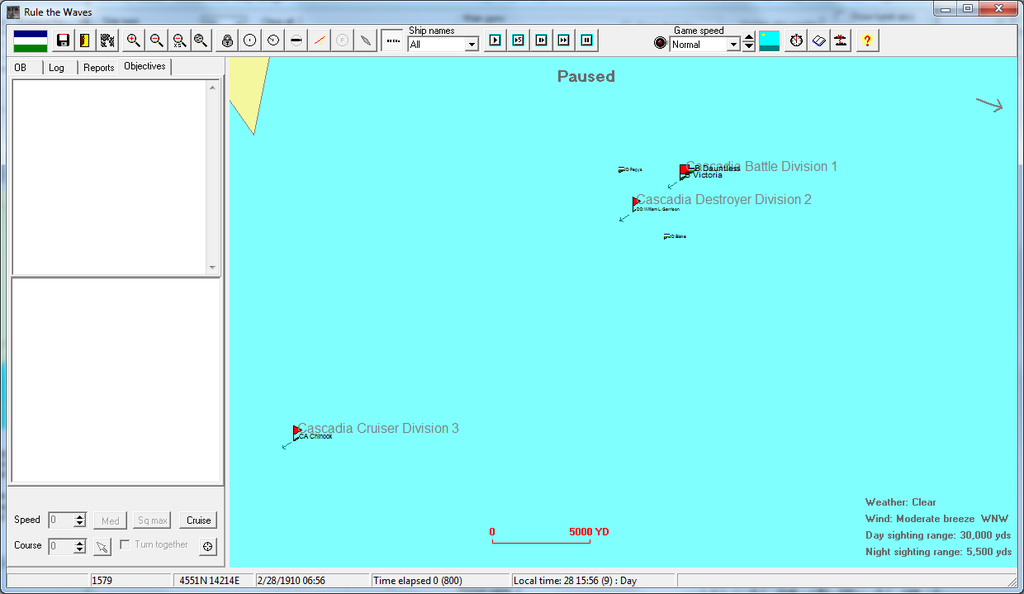

The Allies knew of what was going on through the British and American diplomatic corps and other reports. Lakeland was quick to seize advantage. As government control and army power collapsed across Russia and the Russian fleets were seized by their sailors and returned to port, the Cascadian Navy went into operation. A force of two brigades that had been training in southern Alaska were put on boats and, under escort, carried to Petropavlovsk-Kamchatksiy. The collapse of central authority meant there was no opposition to their landing around the city and taking it. By May 25th, Cascadia had taken possession of all the settlements in the Kamchatka Peninsula. Further landings in Chukotka were planned for June.

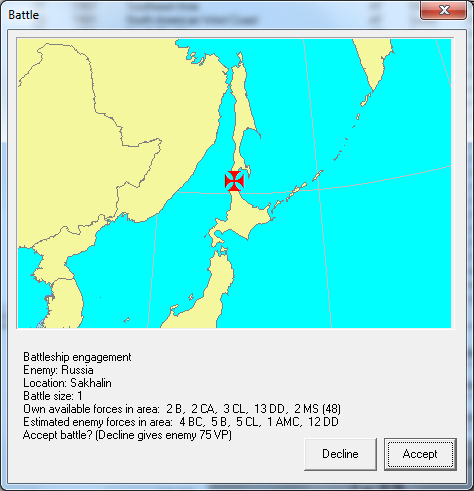

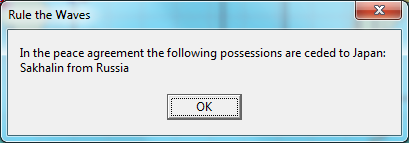

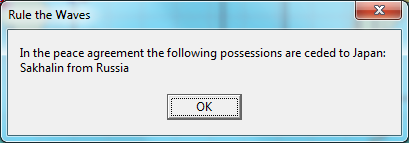

On May 19th, Japanese troops landed on Sakhalin. They would have complete control of the island before the month was out.

The situation in Manchuria was trickier. The Russian officials in Port Arthur, hearing of what happened, had apparently decided they would rather have a "European" power take control of the port. They wired the Russian minister to the Chinese government, who in agreement informed the Cascadian minister in Peking that if Cascadian troops were shipped to the Liaotung Peninsula, the Russian forces would not fire on them and would surrender immediately in return for repatriation. The exuberant minister agreed and wired General Brewer. Before the day was out, a regiment of Cascadian troops, the 2nd Klamath, were aboard steamers making for the peninsula under the protection of the

Chinook and other ships. They arrived on May 16th and took formal possession.

Japanese troops, meanwhile, continued to march behind the retreating Russians. Harbin and Mukden would soon fall to their advance. There was severe aggravation in parts of Tokyo at the Cascadian taking of Liaotung. Japanese leaders resolved to only accept this if Cascadia agreed to Japanese annexation of all of Korea.

When Kerensky's peace offer finally made it to Paris on May 28th, the Cascadian and Japanese representatives replied with conditions: the acceptance of the new government to their territorial dispositions. Cascadia would take over Kamchatka in its entirety and draw a line through the Russian Far East based on the Kolyma and Omolon Rivers, then south of the origin of the Omolon to the Sea of Okhotsk; everything to the east of this line would be placed under Cascadian control. The Russian title to the concession in the Liaotung Peninsula would go to Cascadia. Japan would get Sakhalin and Russian acceptance of the annexation of North Korea. France required a pledge that the new government would sever the alliance with Germany and remain neutral in all further Franco-German conflicts.

Kerensky balked at the scale of the costs. He feared that it might inspire the Army to revolt. But Lenin outmaneuvered him in the Soviets and pushed acceptance. He calculated that with Germany continuing the war, the Cascadians and French would succumb to revolution as well and that any territorial concessions would be undone. Even if this did not happen, the new government had to make peace and accept the sacrifice.

On June 10th, the Russian Soviet signaled to the Allies their acceptance of the term. The new representative of the Russian Soviets signed the agreement with Allied representatives in Paris on June 19th. The Treaty of Sevres, as it would be called, ended Russian participation in the war.

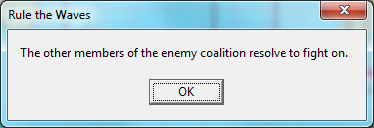

However, a month before then, the German Empire had already made its decision. Germany would still fight on, alone, against her three enemies.

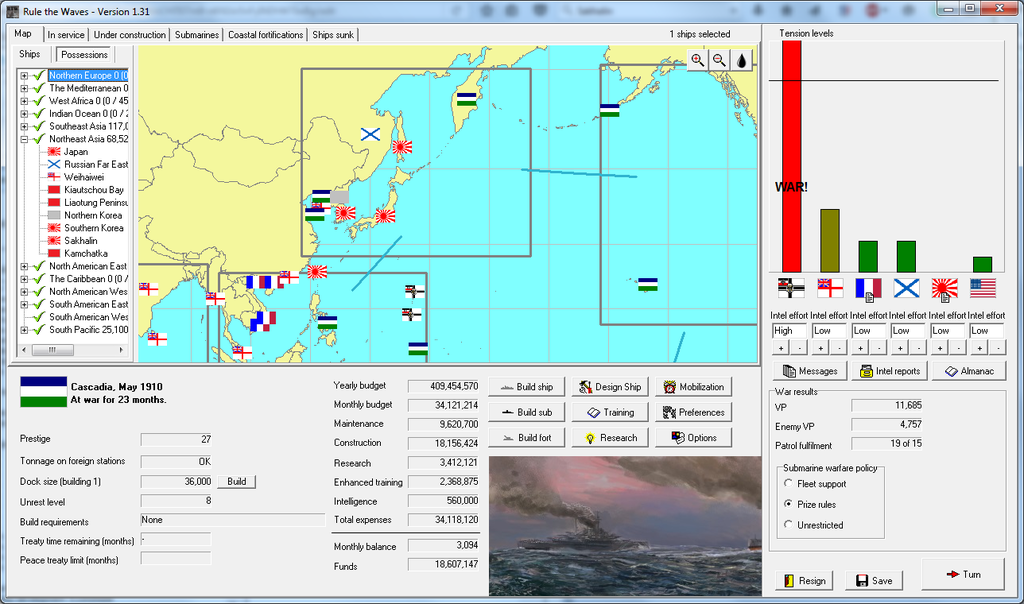

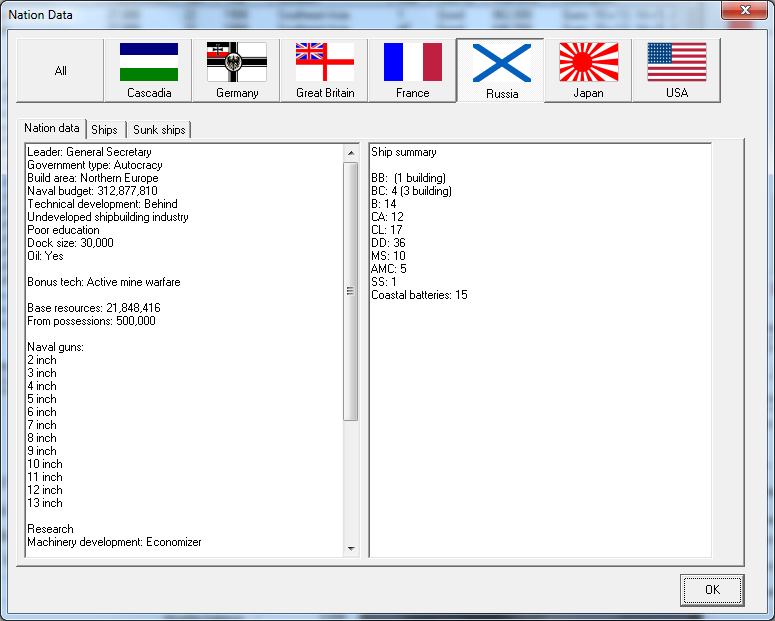

Also, here's the post-war Russian government now:

Author-Player's Note: I will admit that I edited the save file over Northern Korea. The game starts with Northern Korea as a "Neutral" possession, as in not occupied by any of the powers. This, of course, is done to reflect that before the Russo-Japanese War, that region was disputed between Japan and Korea. And historically it went to Japan upon its victory in said war.

Which this war, in part, is this timeline's equivalent of.

But of course this game doesn't reflect that historical reality in the system. Neutral possessions are only taken over by various kinds of events. Ergo I have altered the map data save file (which says where things are in each zone, who rules them, and if anyone has invaded) to make Japan the controller of Northern Korea.

On another note, having the Allied armies take Metz based on my interpretation of the 1500VP "multiple breakthrough" event came mostly from the later Russian Revolution event. These two things gave me the logic of the Russian Army's collapse, and with it the Germans being forced to retreat or be outflanked. I apologize if I interpreted the event wrongly. I'm trying to make things interesting and justify what has happened in the game.

?