Battle of the Fortresses - Eighth Battle of Iserlohn

News of the skirmish between Eihendorf’s fleet and elements of the Yang Fleet turned Duke Lohengramm’s attention towards the Free Planets Alliance, once again.

Background

Fezzan, under the rule of Landsherr

Adrian Rubinsky, had long since been conspiring (with the connivance of the fanatical Terraist Church) to play the Alliance and Empire against each other in service of a long term plan to gain suzerainty over all of humanity. The new balance of power in light of Reinhard’s crushing victories over the Alliance had changed that calculus – Adrian Rubinsky now determined that Fezzan would assist the Empire in destroying the Alliance, thereby uniting humanity. After that was achieved, Fezzan would be in a position to pull the strings - by first assassinating Duke Lohengramm.

Meanwhile, with Fezzan firmly in control of the Alliance economy (with the Alliance being in critical levels of debt due to loans taken out from Fezzan to continue prosecuting the war), and with Job Trunicht in the Terraist Church’s pocket, they would use their control over the Alliance’ authority to corrode the Alliance from within.

Rubinsky took his plan to the Terraist Church representative,

Bishop Degsby, who agreed to take the plan to the Grand Bishop. What the Earth Church did not know was that Rubinsky had his own plans. Where the Church’s plan was to emulate the Christian takeover of the Roman Empire by ‘brainwashing its leaders with religion’, Rubinsky’s plan was to financially control the Lohengramm Dynasty, and pull the strings – Earth Church be damned. He had no desire to see the Grand Bishop in power over all of humanity in some theocracy.

The Plan

The first step in achieving this goal was to ensure the Empire’s military advantage by eliminating Iserlohn Fortress. On that basis, Fezzan conspired with the Empire’s

Admiral Anton Hilmer von Schaft, Inspector-General of the Science and Technology Division. Admiral Schaft had been in that position for 6 years, but so far his only achievement had been the development of directional Seffle particles. Fezzan offered him a plan – moving Geiersberg Fortress to the Iserlohn Corridor.

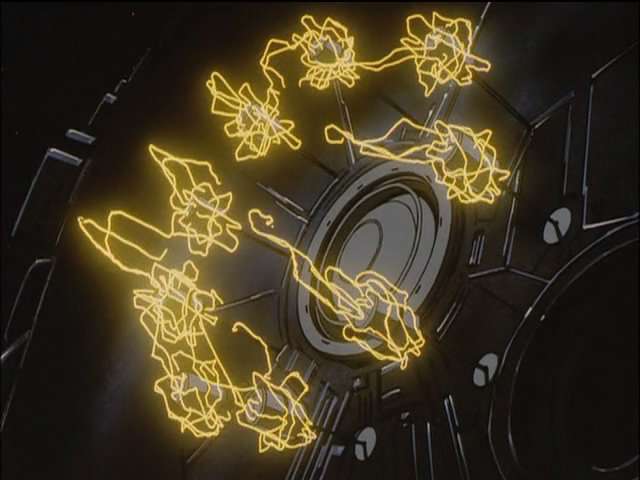

Specifically, twelve warp engines would be affixed around the fortress, allowing the Empire to challenge Iserlohn with a mobile fortress.

Proposed modifications to Geiersberg, before and after

Proposed modifications to Geiersberg, before and after

Schaft made his proposal to Reinhard following a meeting to discuss the defeat of Admiral Eihendorf’s fleet. Hildegard von Mariendorf objected, calling a dispatch at this stage meaningless. With civil life not yet stabilized, she thought it better for Reinhard to devote his energies to internal matters.

Reinhard agreed – hence he would not leave Odin. His subordinates would direct the battle.

Personnel Matters

In the wake of the loss of High Admiral Kircheis, Reinhard made several changes and additions to his high command – most importantly, the promotion of Ernst von Eisenach (also known as “the Admiral of few words”) and Helmut Lennenkampf, who was once Reinhard’s superior in his younger days, to the rank of full Admiral.

Admiral Lennenkampf, left, and Admiral Eisenach, right

Admiral Lennenkampf, left, and Admiral Eisenach, right

At the same time, the ‘Twin Stars’ of Reinhard’s Admiralty, Reuenthal and Mittermeyer, were promoted to the rank of High Admiral – as was Oberstein.

Other changes included the appointment of Admiral Ulrich Kesler to the position of Military Police Chief, and the recall of Commodore Streit (previously a loyal subordinate of Duke Braunschweig) from private life to duty as Reinhard’s aide (together with a ceremonial promotion to Rear Admiral).

The Plan

For the operation itself, however, Admiral Kempf was appointed as commander, with Admiral Müller as vice-commander. Admiral Müller was the youngest of Reinhard’s admirals, being only 27. Though less experienced than the other Admirals in Reinhard’s command, he clearly had excellent skills in both attack and defence.

The selection was met with some puzzlement from Reinhard’s other officers. Amongst themselves, Admiral Bittenfeld noted that, as a big operation, it would make sense to send the two High Admirals – Mittermeyer and Reuenthal. Mittermeyer speculated it was Oberstein’s idea – with Mittermeyer and Reuenthal already favored as the two best officers, he was likely worried that either of them would become “No. 2” in place of Kircheis, causing personnel trouble.

Therefore, Kempf would be in command, in accordance with his experience (at 36 years of age, he was somewhat older than most of the other admirals, with the exception of Lennenkampf) and loyalty – whilst Müller was most suitable for a vice commander.

Kempf and Müller’s fleets departed Odin to oversee the modifications to Geiersberg Fortress in January, Imperial Year 489 (Space Year 798).

Kempf and Müller depart Odin, with Duke Lohengramm seeing them off

Kempf and Müller depart Odin, with Duke Lohengramm seeing them off

Construction at Geiersberg

Construction at Geiersberg

Müller’s flagship Lübeck at Geiersberg, with engineering vessels in the background

Müller’s flagship Lübeck at Geiersberg, with engineering vessels in the background

Kempf’s flagship Jotunheim, overseeing construction

Kempf’s flagship Jotunheim, overseeing construction

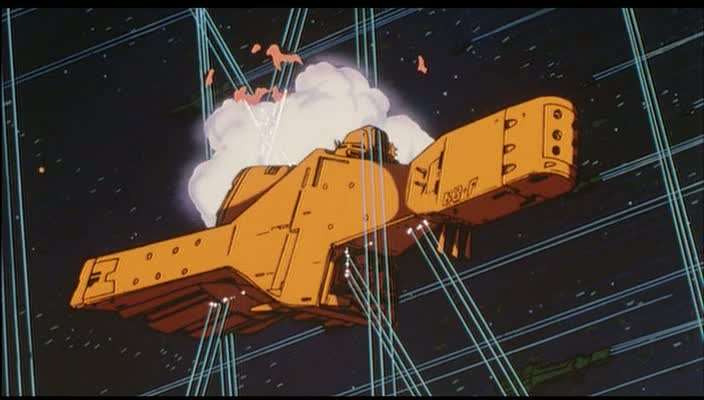

Tests of the sublight engines proved a success – Geiersberg Fortress accelerated from 2,000km/h to 8,000km/h in approximately three seconds. Warp engine tests commenced afterwards.

Geiersberg tests its sublight engines

Geiersberg tests its sublight engines

The final warp test was conducted in the presence of Duke Lohengramm and his top officers.

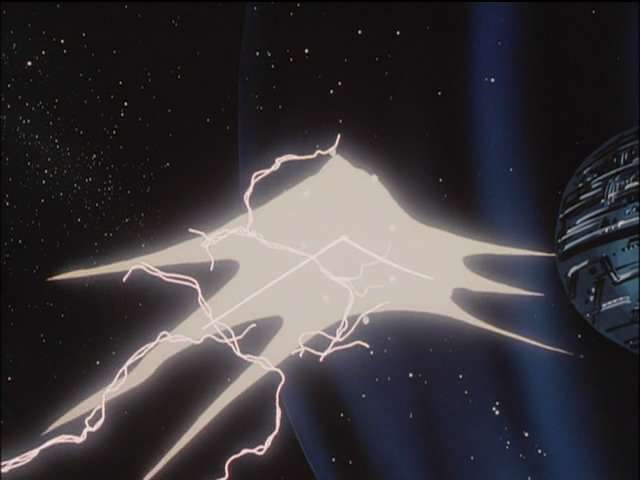

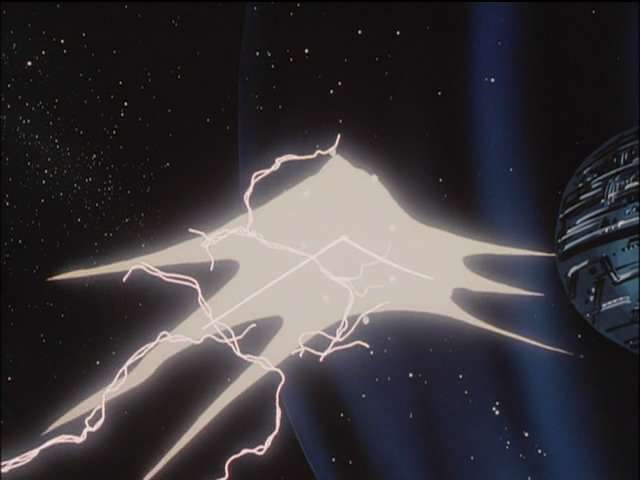

Geiersberg, moments after coming out of warp for the first time, as Duke Lohengramm and his men look on

Geiersberg, moments after coming out of warp for the first time, as Duke Lohengramm and his men look on

The test was successful, and on March 18, 798, Geiersberg Fortress and a fleet of 16,000 ships (the number of ships Geiersberg could accommodate in its berths) and 2,000,000 troops embarked on their journey to the Iserlohn Corridor. Before they left, Reinhard went to Geiersberg to see his forces off - and spent time

alone in the room where High Admiral Kircheis had died, for a time.

Machinations against the Alliance

Rubinsky also understood that to maximize chances of the success of the Geiersberg Fortress plan, Admiral Yang would have to be called away from Iserlohn.

With that in mind, Rubinsky sent his aide,

Rupert Kesserling, to the Alliance High Commissioner’s office on Fezzan, with the news that repayment of 500 billion dinars worth of loans were now due.

Kesserling acknowledged that repayment of the loans was impossible for the Alliance in its precarious economic position, and offered an extension- with the proviso that the Alliance provide certain assurances about its political stability and health as a democracy (specifically referring to the previous year’s coup d’etat). Hinting at the risk of another coup d’etat whereby Fezzan’s capital would be appropriated free of charge for the purpose of ‘national socialism’, Kesserling expressed concerns that Admiral Yang (with his fame, achievements, and critical stance towards the government) might try to overthrow the current government.

The final point in persuading the High Commissioner,

Henslow, was Yang's destruction of all 12 Artemis Necklace satellites protecting Heinessen. Kesserling claimed it may have been an attempt by Yang to eliminate the only obstacle to him attacking Heinessen after he raised his own army, and called for the Council to recall Yang from Iserlohn for an explanation.

Job Trunicht, of course, went along with these concerns – he too was worried about Yang’s popularity and the possibility that he would seek political office. He entrusted the matter to a member of his cabinet,

Mr Negroponte, the National Defence Chairman.

Yang therefore received a summons to appear on Heinessen for an “inquiry”- something with no precedent in the Alliance constitution, or military law, by order of Negroponte. Since it was not a court martial, he did not have to be formally accused of any crime, nor was he entitled to legal counsel.

Yang departed from Iserlohn in a cruiser, the

Leda II – thinking that taking the flagship

Hyperion would send the wrong message. He elected to leave Julian Mintz behind, so that he could make friends his own age while away from Yang. Lt Greenhill accompanied him, with Master Sergeant Louis Machungo accompanied Yang as his sole bodyguard.

The cruiser Leda II, on its way to Heinessen

The cruiser Leda II, on its way to Heinessen

Upon landing on Heinessen, Yang was separated from his compatriots and carted off to a secure location (which he could not leave) by Commodore Veigh, the National Defence Chairman’s Chief of Security. The inquiry commenced an hour later. The inquiry stretched over several days, covering many topics. It was not held everyday, and was held at random times, making the experience even more stressful for Yang. He wrote a letter of resignation and waited for the appropriate moment to hand it over, interested to see if the inquiry would ever decide anything about him, given his necessity for the war effort.

Yang under inquiry

Geiersberg enters the Iserlohn Corridor

Yang under inquiry

Geiersberg enters the Iserlohn Corridor

Whilst Yang endured a psychological lynching and

practical imprisonment, on April 10, the battleship

Ulysses and her escorts, on patrol on the side of the Iserlohn Corridor facing the Empire, detected an object coming out of warp.

Geiersberg emerges from warp

Geiersberg emerges from warp

The Imperial fleet

The Imperial fleet

Quickly realizing the danger, they beat a speedy retreat to Iserlohn. Hearing the report, Admiral Merkatz quickly realized the identity of the fortress.

Schneider, ever at Merkatz’ side, apprised

Rear Admiral Alex Cazerne of Geiersberg’s capabilities – 45km in diameter, its surface covered in ceramic, alloy, and hydro-metal armor, and armed with the Vulture’s Claw, a solid X-Ray beam cannon, with a wavelength of 100 Angstroms and a power output reaching 740TW, it was slightly smaller than Iserlohn Fortress, but almost evenly matched in terms of firepower with Iserlohn’s Thor Hammer.

Cazerne knew they were in a predicament – they didn’t have the forces to win, and they were leaderless. Even if Yang were to leave Heinessen immediately, it would take at a minimum four weeks for him to return. Cazerne ordered preparations be made to launch the fleet and evacuate Iserlohn’s civilians. A hyperspace message was also sent to Heinessen requesting reinforcements. With Geiersberg moving at sublight (the Empire determining it impossible to use warp within the Corridor), the fortresses were fourteen hours from entering the firing range of their main guns.

Cazerne strategy was to hold out until Yang could return, concentrating on defence and responding to enemy attacks when necessary. Rear Admiral Attenborough made one addition to that plan – the enemy could not know Yang was not present.

Yang is released

When the communication reached Heinessen, Yang was again before the inquiry. With his patience at an end, he attacked the inquiry for their false patriotism and cowardice and prepared to present his letter of resignation – just as the call came through to the Defence Chairman. The inquiry was suspended, and Yang was released to go and defeat the Imperial fleet invading the corridor, with Job Trunicht’s agreement. Before leaving, Yang made it clear that the only reason he was going was because his friends were there.

Negroponte was forced to resign by Job Trunicht (with the promise of another position for taking the fall).

Yang met Lt Greenhill, Master Sgt Machungo, and Admiral Bucock outside.

The question of what reinforcements to send was then decided – Bucock had intended that the 1st Fleet, under the command of Vice Admiral Paetta (Yang’s superior at Legnica, 4th Tiamat, and Astarte) be placed under his command, as the only full fleet available.

Unfortunately, the National Defense Committee, under its new Chairman, Walter Islands, refused to give the 1st Fleet permission to launch, arguing that it would leave Heinessen undefended. Islands would only allow Admiral Bucock to muster ships assigned to defence and police roles in each star system. Bucock was able to provide only four independent squadrons - 5,000 ships. It was a hybrid, dressed-up force.

Rear Admiral Morton, the former Vice Commander of the 9th Fleet (who saved the 9th Fleet from total annihilation in the Alviss System), was provided to assist, as was a Rear Admiral Sandle Alarcon (a man who had been court-martialed for war crimes, but who had been acquitted due to lack of evidence).

Battle Commences

Immediately after entering effective main gun range (600,000km), Admiral Kempf

greeted Iserlohn from Geiersberg’s command centre (hoping to speak to Yang Wen-li). Acknowledging that they would not surrender, he let them know he was praying for their good fortune in battle. Iserlohn did not respond. Kempf then ordered the main gun to fire.

Fire!

Fire!

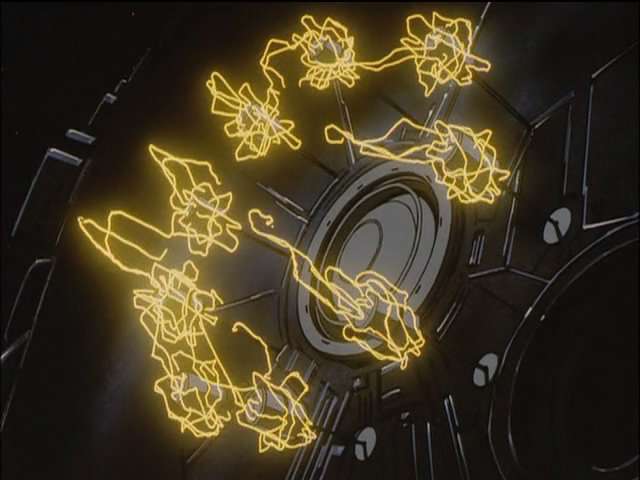

The Vulture’s Claw firing sequence

The Vulture’s Claw firing sequence

Iserlohn’s walls had never been pierced by external attack – they were covered with a quadruple layer of hydro-metal – thought impenetrable against any weapon. Attacks by missiles and explosive were absorbed, whilst beam weapons were merely reflected off. But they had never been struck by a weapon like the Vulture’s Claw.

The Vulture’s Claw pierced Iserlohn’s outer walls – damaging Block RU-75 of the Fortress and killing all of the more than 4,000 troops within. Whilst damage to he wall could not be repaired, the hydro-metal alloy layers quickly recovered.

The hydro-metal moves back into place

The hydro-metal moves back into place

General Schönkopf advocated an immediate counter-attack – they couldn’t afford to sit and wait for the second shot, and by firing back with the Thor Hammer, the enemy would know they would both destroy each other if the main gun fire continued. A stalemate would ensure, and they would gain time for Yang to return.

There was a lull in hostilities between the fortresses after Iserlohn returned fire.

The Thor Hammer strikes back

The Thor Hammer strikes back

With the corridor full of electromagnetic and jamming waves,

Rear Admiral Murai surmised that they intended to invade Iserlohn by transporting infantry on landing ships, through the chinks created in Iserlohn’s armor.

Brigadier General Schönkopf advocated a response in kind, but the idea was too slow in coming. The Imperial troops were

already making their move – gun tower #24 reported enemy landing ships in the vicinity. Schönkopf led the Rosenritter to intercept them.

Imperial Panzer Grenadiers swarm out of their landing ships

Imperial Panzer Grenadiers swarm out of their landing ships

The Rosenritter emerge from the floating gun turrets

The Rosenritter emerge from the floating gun turrets

Battle is joined

Battle is joined

The attack was

defeated – with the Rosenritter causing heavy casualties, Imperial morale was broken when one of the Panzergrenadiers realized who they were facing and made it known. The Rosenritter did not have the combat all their own way – attempting to give chase too closely, some of their number were wiped out by beam cannon and missile fire from the departing landing ships (which were themselves destroyed by the fortresses guns).

Parthian shots

Parthian shots

Meanwhile, on Iserlohn, Schönkopf pressed for an attack on Geiersberg using infantry – Rear Admiral Murai vetoed the plan. Noting that they had captured some Imperial troops in the battle, the situation could be reversed on Geiersberg – and any captured Alliance troops could disclose that Yang was not present. Indeed, that risk already existed – numerous Rosenritter were unaccounted for, and could have been captured.

Kempf was disappointed that the landing team had failed, but was not unprepared. After three days, the next phase began - Müller’s fleet launched from Geiersberg, and began

swinging behind Iserlohn, being careful to stay out of the Thor Hammer’s range whilst doing so.

Assuming it was a diversion to draw the Thor Hammer off target, and noting that an ordinary fleet would be unable to breach Iserlohn’s defences, the fortresses floating gun turrets were deployed to deal with Müller.

Müller’s fleet on the move

Müller’s fleet on the move

The floating gun turrets change position

The floating gun turrets change position

Falling for the Imperial trap, Geiersberg accelerated closer to Iserlohn. Cazerne ordered the Thor Hammer to be charged, assuming that the sight of it would stop Geierberg’s advance.

Geiersberg charges

Geiersberg charges

Instead, Iserlohn was struck with the Vulture’s Claw, damaging gun turrets and badly damaging Block LB-29. The Thor Hammer returned fire, only for the Vulture’s Claw to reply once more, Geiersberg advancing all the while.

The Imperial assault would normally have been reckless – Geiersberg’s armor was weaker than that of Iserlohn. However, it was noted that though Block RG-25 had been damaged by the last hit, the damage was not as severe as previous hits, and yet there was no evidence of the Vulture’s Claw having suffered a power loss. When Iserlohn next fired in response, there was no apparent effect on Geiersberg’s surface.

Next, the Thor Hammer was submerged - Geiersberg’s gravity had created a ‘high tide’ – pulling the hydro-metal on Iserlohn’s far side towards the side facing Geiersberg, simultaneously leaving the far side of Iserlohn exposed to Müller’s fleet, and strengthening both Geiersberg and Iserlohn's armor facing each other.

The Thor Hammer submerges

The Thor Hammer submerges

Müller’s fleet immediately opened up whilst Geiersberg halted.

Gun turrets on Iserlohn’s now-exposed outer walls are quickly silenced

Gun turrets on Iserlohn’s now-exposed outer walls are quickly silenced

Murai ordered the adjustment of Iserlohn’s gravity field to return to normal status. The station fleet commanders – Rear Admirals Attenborugh, Fischer, and Nguyen,

urged a launch. With the Vulture’s Claw in front and Müller’s fleet behind, the fleet could only launch from a suitable blindspot, as suggested by Attenborough.

Laser hydrogen missiles from Müller’s fleet

breached Iserlohn’s outer wall at point LZ-2-5.

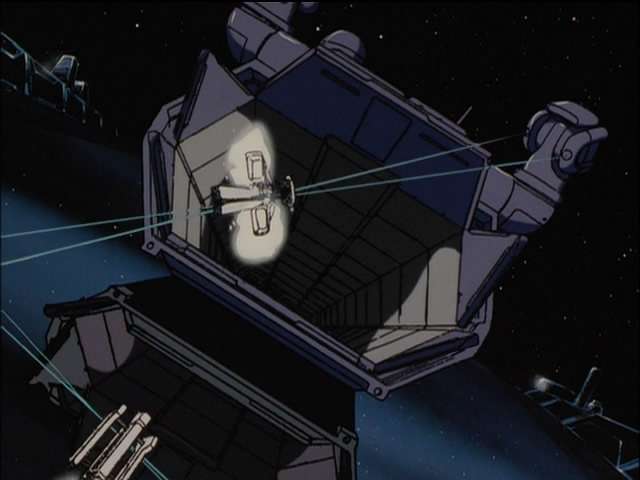

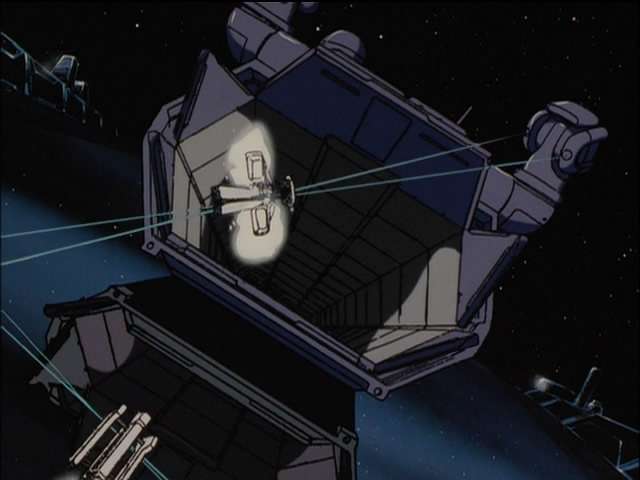

Lübeck and the breach in Iserlohn’s walls

Lübeck and the breach in Iserlohn’s walls

Müller then launched 2,000 Valkyrie fighters to secure air supremacy within the sphere, with the intent of landing 50,000 troops to occupy the command centre once it had been achieved.

Valkyrie fighters zoom past Imperial landing ships

Valkyrie fighters zoom past Imperial landing ships

Panzer grenadiers fix axe-heads to their rifles. No, really!

Panzer grenadiers fix axe-heads to their rifles. No, really!

Iserlohn’s Air Corps 1 and 2, under Commanders Poplin and Konev, went to the defence.

Iserlohn fighter launch tube rises…

Iserlohn fighter launch tube rises…

…and destroys a potential intruder

…and destroys a potential intruder

It was at this point that Admiral Merkatz approached Cazerne and

asked for temporary command of the station fleet to ease the situation. Cazerne agreed. Merkatz took command aboard the

Hyperion.

Admiral Kempf was pleased and thought victory was assured, joking with Müller that the Iserlohn Corridor would be renamed the Geiersberg Corridor – or the Kempf-Müller Corridor. To Müller, for Kempf to celebrate victory before it was achieve was distinctly unlike him. In any event, Müller decided that they would take an unnecessary beating if the battle went on much longer, and decided to use “it” - six unmanned destroyers would charge into Iserlohn’s docking port.

Before preparations were complete, the Thor Hammer appeared – as a type of floating gun tower, it had been moved near the breach in Iserlohn’s walls, and though it could move no closer to get an optimum firing angle on Müller’s fleet, the odd angle it fired at was close enough.

The Thor Hammer’s oblique shots

The Thor Hammer’s oblique shots

Müller was forced to temporarily retreat and regroup as the Thor Hammer fired a second time. Moving to the Thor Hammer’s blindspot, Müller saw the launch of the station fleet. Deciding on fleet battle, Müller moved to intercept them as they moved along the outside of the fortress, apparently refusing battle. Wary of a trap to lure them into the Thor Hammer’s firing arc, he declined to pursue, and instead took a counter-clockwise course around the other side of the fortress to attack the head of the fleet.

Müller’s fleet moves around Iserlohn

Müller’s fleet moves around Iserlohn

Unfortunately, Iserlohn’s floating gun towers were lying in wait. As they opened up, the stationed fleet attacked Müller from the 4 o’clock direction and then surrounded his fleet.

Müller attempts escape …

Müller attempts escape …

But …

But …

Rear Admiral Nguyen's flagship Maurya, in new and ostentatious livery, attacks from below

Rear Admiral Nguyen's flagship Maurya, in new and ostentatious livery, attacks from below

Triglav attacks from above

Triglav attacks from above

Müller surrounded whilst Kempf watches

Müller surrounded whilst Kempf watches

In response, Müller took a spherical formation, placing his weaker ships in the centre, hoping to hold out for reinforcements from Geiersberg.

Kempf could not order the Vulture’s Claw to fire – Müller’s fleet would be in the firing line. Instead, he ordered

Rear Admirals Eihendorf and Patricken of his own fleet to rescue Müller with 8,000 ships.

On the way to launch, Eihendorf and Patricken

speculated on Kempf’s position – he was being unusually hasty – probably borne of the hope that in succeeding, he would be able to narrow the gap between himself and Mittermeyer and Reuenthal. Failure could mean demotion and transfer to an ‘easy’ post.

With the aid of the reinforcements, Müller succeeded in breaking out of the encirclement. Admiral Merkatz ordered the station fleet not to try to hard to stop it, and then fired at their tail as they retreated. Pursuit was halted after a short while, and Müller retreated to Geiersberg.

Müller breaks out and meets up with reinforcements

Müller breaks out and meets up with reinforcements

Kempf ordered Müller to the rear, saying that Müller had fought well, but for no gain. Müller wondered if Kempf was doing so in order to monopolize all the credit for success.

It was 15 April 798. In response to a request from Odin for a report on the battle’s progress, all Kempf could offer in reply was “Our fleet is at an advantage”.

Meanwhile, Müller received a report that a POW, before dying of his wounds, had revealed that Yang was not on Iserlohn. Müller then received another POW report, who claimed that they had been told to say Yang was not present, to confuse them.

Müller was

not convinced – that Yang was not at the fortress was too absurd to be a fabrication, and as a ploy, it seemed unusually passive and roundabout for someone like Yang. Müller decided that Yang was indeed not present, and ordered a net of 3,000 reconnaissance picket ships to disperse throughout the whole corridor – with the intent they would wait for his return and take him prisoner, far from Iserlohn.

Kempf, refusing to believe Yang was not present, ordered the deployment countermanded. Müller despaired, had no choice but to obey.

Reinforcements from Odin

Duke Lohengramm was not pleased with Kempf’s “report”. He had hoped Kempf could accomplish more, but reasoned that all he was capable of was dealing a withering blow to the enemy. It was apparent to Reinhard that Kempf had failed to realize his objective was to neutralize Iserlohn, not capture or occupy it. Instead of being creative and simply ramming Geiersberg into Iserlohn, he had made Geiersberg his base and achieved nothing in a set-piece battle.

Great minds …

Great minds …

High Admiral Oberstein took responsibility for recommending Kempf, admitting he had been mistaken about Kempf’s capabilities. Reinhard thought he was being coy, and noted he himself bore ultimate responsibility. He also noted that Admiral Schaft was the root cause of the entire affair, having been the reason the “needless plan” had been created.

Reinhard ordered Mittermeyer and Reuenthal to take their fleets to the Iserlohn Corridor to join Kempf and Müller. Dismissing their concerns that Kempf would see it as an attempt to take away his credit for victory, Reinhard noted that Kempf might not even be winning. He gave them standing orders not to recklessly enlarge the battle, but otherwise, to proceed as they saw fit.

Mittermeyer and Reuenthal made plans accordingly – if there was a stalemate on arrival, then their arrival was justified. If Kempf was winning, their deployment was pointless. If Kempf was losing, then they would likely be too late. They proceeded on the basis that Kempf would be losing and under pursuit, so they could react quickly to such an eventuality.

Meanwhile, Yang, still en route to Iserlohn, had surmised that Duke Lohengramm would send reinforcements – the space around Iserlohn would have to be under Alliance control before they arrived, or there would be no chance of victory. He had also prepared a measure to counter any attempt to ram Iserlohn with Geiersberg.

Yang Returns

Yang’s hodge-podge fleet ran into an Imperial reconnaissance squadron of 50 ships. Yang was glad they had been spotted – the Imperial commander would have to decide whether to continue attacking Iserlohn, turning around to attack the reinforcements, dividing their forces and fighting on two fronts, trying to defeat both forces with careful timing, or retreat. Leaving them with few good options, Yang had the upper hand.

Kempf, too, saw the arrival of Alliance reinforcements as a good thing. They would retreat at high speed from Iserlohn, and the stationed fleet, thinking they were retreating because the reinforcements had come, would be drawn out. At that point, Kempf planned to reverse course and counter-attack, which would convince the station fleet that no reinforcements had arrived, and force them back into Iserlohn. Following that, they could then focus on the Alliance reinforcements without worrying about the fleet at their rear.

Müller noted that the timing would be extremely tight – and suggested that Geiersberg be left where it was to cover Iserlohn. Kempf agreed.

Kempf’s plan

Kempf’s plan

When the Imperial fleet began to retreat, Rear Admiral Murai suggested it might be a trap to convince them their reinforcements were close by. Julian Mintz, offering his opinion at the suggestion of General Schönkopf, correctly guessed at Kempf’s plan. After all, the Imperial force was definitely aware by now that Iserlohn was taking a defensive strategy and would not commit its forces too far, and in that context, trying to seal the station fleet in to deal with Alliance reinforcements made the most sense.

Admiral Merkatz agreed, and proposed that the station fleet merely pretend to retreat all the way into the fortress. Cazerne gave him command of the station fleet once more. Merkatz requested Julian to accompany him on the

Hyperion.

Fleet battle

The station fleet moved out of Iserlohn as planned in response to Kempf’s feigned retreat. Kempf, in direct command of his 12,000 ships (having transferred back to his flagship

Jotunheim) ordered a rapid reverse course and counter-attack.

Jotunheim on the move

Jotunheim on the move

The Alliance fleet caught in the cross-fire

The Alliance fleet caught in the cross-fire

Schneider, Merkatz, and Mintz on the Hyperion

Schneider, Merkatz, and Mintz on the Hyperion

The station fleet returns fire

The station fleet returns fire

Merkatz ordered a slow withdrawal back into Iserlohn in response. Kempf continued his attack until they were just out of range of the Thor Hammer. Pretending to hide within the fortress again, the station fleet waited inside Iserlohn’s hydro-metal armor layer, ready to leave again when the time was right.

Kempf turned to deal with the reinforcements. Yang could only hope that Admiral Merkatz, veteran officer that he was, would assist him, and that Julian would remember what Yang had taught him. If not, his 5,000 ships would not be able to hold out against the Imperial force for long.

Entering firing range, Yang’s fleet went into retreat, keeping the speed differential between the two fleets at zero. For five minutes, Kempf pursued, with the distance between the fleets remaining the same. Realising that the enemy was trying to gain time, he ordered the fleet to increase speed, brining them within firing range.

Rear Admiral Alarcon

Rear Admiral Alarcon

Yang pulls back

Yang pulls back

Kempf catches up

Kempf catches up

The Leda II deflects a direct hit

The Leda II deflects a direct hit

Yang’s special coffee is a casualty

Yang’s special coffee is a casualty

Yang ordered a change in formation – a hollow cone shape, which Kempf advanced into, bringing a rain of Alliance fire from all sides.

The Alliance fleet changes formation

The Alliance fleet changes formation

Kempf falls into the hole

Kempf falls into the hole

The Imperial fleet caught in a withering cross-fire

The Imperial fleet caught in a withering cross-fire

Kempf ordered his fleet to break through the centre and turn around to counterattack the ‘outside’ of Yang’s formation. It was an impossible order – Yang’s formation was fully occupying the useable space of the Iserlohn corridor. Before he could process the information, he came under attack from the station fleet to his rear. Surrounded, the Imperial force was being wiped out. In the melee, Rear Admiral Patricken’s ship was destroyed.

Merkatz attacks

Merkatz attacks

Rear Admiral Patricken is killed when his battleship, the Langenberg, is destroyed

Rear Admiral Patricken is killed when his battleship, the Langenberg, is destroyed

Well … you know. Memes.

Well … you know. Memes.

A hopeless situation for Kempf

A hopeless situation for Kempf

Müller, level headed in a crisis, did his best, ordering the well-armored ships to the front, the damaged ships in the middle, and holding his fleet’s formation tight.

Lübeck in battle

Lübeck in battle

Jotunheim fighting

Jotunheim fighting

Kempf ordered the fleet to press forward with the intent of

breaking through into Alliance space. In response, Yang ordered another change in formation, effectively closing the entrance to Alliance space, and further decimating the Imperial force with beam cannon artillery barrages. Rear Admiral Eihendorf’s fleet was totally destroyed in the attempt.

The hole is closed

The hole is closed

Combined-beam artillery attacks decimate the Imperial force

Combined-beam artillery attacks decimate the Imperial force

With a breakthrough now impossible and defeat clear, Rear Admiral Fusseneger, Kempf’s Chief of Staff, suggested retreat. Kempf would not be dissuaded – in the chaos, he noticed Geiersberg’s

real utility.

Kempf ordered the remnants of his fleet to take a dense formation and break through the enemy to their rear, back to Geiersberg. Merkatz let them pass as before, placing priority on joining up with Yang.

Hyperion meets up with Leda II

Hyperion meets up with Leda II

At this point, Rear Admiral Alarcon urged pursuit to annihilate the enemy before they reached Geiersberg. Yang

refused, saying the enemy was fine where they were. As the two Alliance fleets united, Kempf

docked the

Jotunheim at Geiersberg and ordered a collision course. At the same time, Müller ordered all ships to prepare escape shuttles for launch to evacuate Geiersberg’s crew.

Evacuation

Evacuation

The Thor Hammer was prepared to fire, but Geiersberg was too close. Yang was prepared. Noting that ship guns were useless on the fortress proper, his combined fleet concentrated its firepower on one of the sublight engines attached to Geiersberg’s surface.

Target

Target

With two full fleet barrages, Geiersberg was thrown off course, and it turned away from Iserlohn rapidly, ramming into orbiting Imperial ships as it went, out of control.

The Thor Hammer soon had a firing angle, lancing out to strike Geiersberg and destroying more Imperial ships in the process.

Geiersberg suffers a mortal wound

Geiersberg suffers a mortal wound

Kempf, dying from wounds received whilst in Geiersberg’s command center, ordered an evacuation of all hands. His last words to Rear Admiral Fusseneger were “My apologies to Müller.”

Kempf’s end

Kempf’s end

Jotunheim is destroyed at dock

Jotunheim is destroyed at dock

Geiersberg exploded before the evacuation was complete.

The explosion threw an Imperial battleship into Müller’s flagship

Lübeck, damaging her and wounding Müller, who suffered six broken ribs.

He ordered the ship’s doctor to treat him on the bridge, so he could command the remnants of the fleet – only 700 ships - in the retreat back to Imperial space. After being informed of Kempf’s death and his last words by Fusseneger, he vowed revenge on Yang.

After Yang transferred his flag back to the

Hyperion, he was informed that Rear Admiral Nugyen van Huu and Rear Admiral Alarcon had taken their respective fleets - 5,000 ships in all - into Imperial territory, in pursuit of the retreating Imperial fleet. Yang ordered immediate pursuit with all ships, to bring them back before disaster befell them.

This is for Kempf!

Mittermeyer and Reuenthal were approaching the Iserlohn Corridor as they met Müller’s force.

The damaged Lübeck pulls alongside Mittermeyer's flagship Beowulf

The damaged Lübeck pulls alongside Mittermeyer's flagship Beowulf

Reuenthal’s flagship Tristan

Reuenthal’s flagship Tristan

Learning what had happened, Mittermeyer sent Müller to the rear and resolved to avenge Kempf, well prepared to counter-attack the Alliance pursuers.

Mittermeyer and Reuenthal advanced at full speed to launch a surprise attack. His Rear Admirals - Bayerlein, Bülow, Droisen and Sinzer were ordered to follow his usual procedures.

Nguyen, heading the pursuit from his flagship, the

Maurya, spotted the enemy fleet in front of him, but only with maximum sensor magnification. Rear Admiral Alarcon, trying his hardest to show up Yang’s fleet, pressed ahead as well.

It was then that Mittermeyer attacked them from above.

Beowulf and company descend on the Alliance fleet with a vengeance

Beowulf and company descend on the Alliance fleet with a vengeance

At the same time, the fleet they were pursuing turned to fight. Admiral Nguyen realized too late it was not Müller's shattered force, but

Rear Admiral Bayerlein’s (incorrectly depicted in Vice Admiral's uniform) fleet.

Nguyen realizes his error

Nguyen realizes his error

The Alliance fleet ordered a course change straight ‘down’ – but ran straight into Reuenthal’s fleet.

Reuenthal enjoys himself.

Reuenthal enjoys himself.

All 5,000 ships were wiped out in moments, and both Nguyen and Alarcon were killed in action.

Nguyen’s final moments

Nguyen’s final moments

His battleship Marduk blown in half, Rear Admiral Alarcon meets his fate when the forward section collides with a friendly cruiser

His battleship Marduk blown in half, Rear Admiral Alarcon meets his fate when the forward section collides with a friendly cruiser

Mittermeyer wondered how these could be the same men that had fought them to a standstill at Amlitzer.

Yang’s fleet, an additional 10,000 ships, then arrived. Though both Mittermeyer and Reuenthal wanted to fight Yang himself, they agreed a battle would be meaningless, and started for home. They would take Yang’s head some other time.

Yang wondered to himself how the battle would have gone if Siegfried Kircheis had been alive. The remainder of the Yang Fleet returned to Iserlohn.

Aftermath

Lübeck arrives home, with Beowulf and Tristan also visible

Lübeck arrives home, with Beowulf and Tristan also visible

Geiersberg Fortress had been destroyed, and nearly 15,000 ships had been destroyed or damaged, with 1,800,000 casualties- Kempf had lost 90% of the forces assigned to him. Duke Lohengramm was enraged, but understood that men like Müller were hard to find – he would not risk the life of a good man in a useless battle again.

When Müller returned, expecting the worst and taking full responsibility for losing the battle, Lohengramm refused to hold him responsible, and commended him for his return, only noting he should atone for losing one battle by being victorious in the next. It would take him some 3 months to recuperate from his wounds.

Kempf was promoted to High Admiral, posthumously, and received a funeral with full honours – unprecedented treatment for someone who died in defeat. Reuenthal later put to Mittermeyer that it was all a show – Kempf had been of no further use, and it cost Duke Lohengramm nothing to shed tears and glory for the dead.

Admiral Schaft was placed under arrest. The Empire had been provided with papers implicating Schaft with corruption, embezzling public funds, tax evasion, breach of trust, and betraying military secrets. The proof had been provided by Fezzan, who had decided to cut Schaft loose given that he was no longer useful, and making ever more demands on them. Duke Lohengramm ordered increased surveillance was placed on the Fezzan’s Ambassador’s Office - not caring whether they noticed it or not.

Though Fezzan’s ploy to assist the Empire had been a debacle, their main plan plowed ahead.