PeZook wrote:As for the correlation between employment and automatization, it will hold true for a long time, but it breaks down when the labor investment needed to increase productivity approaches zero.

For example, if the "alpha" exponent in the function is zero (that is - added labor input does not lead to increased productivity), the function breaks and only capital and technology starts counting.

It will happen only if machines are able to produce, service and improve themselves, leading to a completely automated production process.

While not applicable in the immediate future, even if eventually self-replicating technology allowed almost zero human workforce per million tons produced, like quadrillions of tons output, such wouldn't necessarily mean the end of employment.

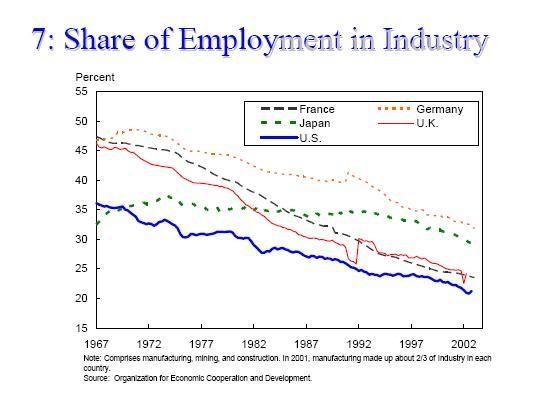

Even today, manufacturing is only a limited percentage of the total jobs in a country with mainly service sector employment like the U.S. Elimination of all service-sector jobs from teachers to bureaucrats to psychologists doesn't tend to occur in the foreseeable future.

Besides, if the self-replicating machines are not sapient, the industrial system needs the intellectual labor of humans to have maximum capabilities.

If the self-replicating machines include sapient ones, then there may be a group of artificial people who don't strictly need any assistance from baseline

homo sapiens people. Such doesn't necessarily rule out employment for the latter, though. In the current world, the group of people which calls itself the United States doesn't strictly need anything from the people in a number of tiny countries, but that doesn't prevent business arrangements.

A sufficiently advanced sapient AI or upgraded post-human individual might be better at doing any particular job than a baseline human. That doesn't necessarily mean the latter couldn't possibly find employment. In the current world, the average U.S. farmer produces much greater crop yields than the average third-world farmer. But the work of the third-world farmer still produces something of value, and, however limited, it is typically as much (actually more) beyond the food he needs to survive than it was centuries ago.

That's related to the idea of comparative advantage, like this example:

A country can have an absolute advantage in the production of a good without having a comparative advantage. [And an entity like a country or an individual can have a comparative advantage despite being less efficient in absolute terms]. Comparative advantage is what determines whether it pays to produce a good or import it. Assume that there are only two goods, cars and computers, and one productive resource which is some composite of land, labor, and capital. Assume also that producing 100 cars requires two units of the productive resource (PR) in the United States and four units in Brazil, and producing 1,000 computers requires three units of PR in the United States and four in Brazil.

[... In this example,] Americans have an absolute advantage in producing both cars and computers.

It may seem that Americans can realize no gain by trading with Brazilians. Why not produce both cars and computers here? Because it costs more to produce computers in the United States than in Brazil [not in absolute terms but in opportunity cost]. All costs are opportunity costs. The cost of producing computers is the cars that could have been produced. Using the three units of PR required to produce 1,000 computers in the United States requires sacrificing the production of 150 cars. Using the four units of PR required to produce 1,000 computers in Brazil requires sacrificing only 100 cars.

So even though Americans have an absolute advantage in producing computers, Brazilians have a comparative advantage. Compared to what has to be sacrificed, Brazil produces computers for only two-thirds as much as it costs in the United States. The United States, of course, has a comparative advantage over Brazil in the production of cars. Producing 100 cars here costs 666 computers, while producing 100 cars in Brazil costs 1,000 computers.

Clearly the United States benefits from specializing in cars, which it produces more cheaply than Brazil, and trading with Brazil for some of the computers it produces more cheaply. If, for example, the United States produced both cars and computers it might devote 70 units of PR to car production and 30 units to computer production, yielding 3,500 cars and 10,000 computers. If Brazil produced both products, it might devote 56 units of PR to car production and 24 to computer production, yielding 1,400 cars and 6,000 computers. On the other hand, by specializing in their comparative advantages, the United States can produce 5,000 cars and Brazil can produce 20,000 computers, or a total of 100 additional cars and 4,000 additional computers.

example

In the future, perhaps one day any non-upgraded human worker might have inferior productivity to some AI or posthuman workers. But keep in mind that almost any individual human worker already has inferior productivity to some other person (e.g. 99% of electricians aren't the best 1%), such as a relatively unskilled worker versus a skilled worker, yet even unskilled workers can still do work that's worth more than the food they eat.

Besides, short of a scenario with a dystopic society that has people genocided or dying of starvation, people consume food, housing, and more anyway. The society only gains by having people employed instead of having them consume the same resources while producing nothing.

Outside of pessimistic scenarios, a hypothetical future society with almost unlimited self-replicating industrial production would be benevolent and intentionally aim to ensure appropriate employment is available for everyone. For example, if you're converting quadrillions of tons of available raw materials into industrial production, sparing the miniscule portion of that sufficient for paying wages to people and providing great accomodations is trivially easy. What most approaches utopia would be a complicated question, but it would seem to involve less hours of work than today while not having utterly unproductive citizens either, being somewhere in between.

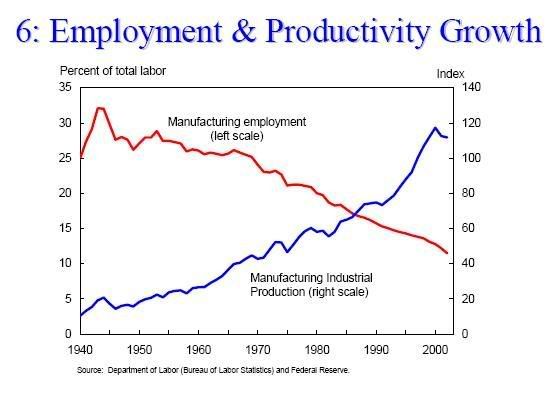

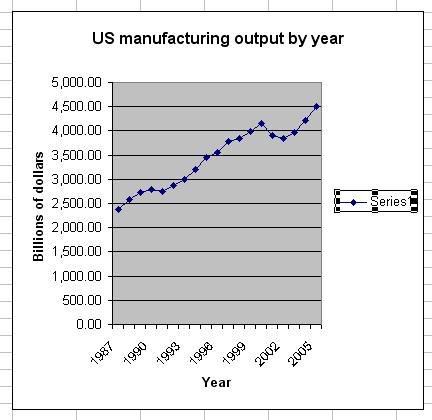

Of course, one has gotten into a far future discussion here, while my past post on historical trends over past decades is more relevant for the near-term foreseeable future: For now, the ratio of human labor requirements to economic output remains very far from zero, automatically demanding employment.