Essay: The Origins and Causes of the U.S. Civil War

Posted: 2008-04-02 05:32pm

Despite the fact that it has been over for 143 years, the American Civil War's causes, the motives behind the secession of the Deep South, and even the legality of secession itself are still matters of hot debate in historical circles. There has been so much historical revisionism on the subject (on both sides, no less), that it has become difficult to get a clear account of the reasons behind it, although the facts of the actual events are widely available.

In this thread, I'm going to lay out the facts as I see them. I freely admit to being a Unionist and ardent anti-Confederate, but feel that these are positions borne out by the objective facts of the matter rather than damaging biases. Make of that what you will.

First, the motives behind secession.

Too often, you will see apologists for the Confederacy claiming that the South did what it did because they saw that Abraham Lincoln was a despotic tyrant in the making, that he would subjugate the rights of the people and crush the states beneath the boot of the federal government. "Lincoln the Tyrant" is a popular trope, spurred onward by the usual grain of truth that gives such things their lasting appeal: Abraham Lincoln did, as President, suspend habeas corpus, raise an army without the consent of Congress, and, yes, ordered the forfeit of property on the part of Confederates (i.e. freed the slaves, though it's not often put like that in a criticism for obvious reasons). You see this repeated over and over in neo-Confederate and anarchocapitalist circles; for instance, a look through the titles of Thomas DiLorenzo's essays shows an obsession with writing extensive character attacks on President Lincoln, and while probably the most prolific, he's not the only one.

There are obvious problems with this approach, however. The most glaring is that none of the things that Lincoln did that earn so much scorn could have been done outside the context of the Civil War. In other words, far from predicting Lincoln's behavior and seceding to avoid it, the southern states were the catalyst for his behavior! After all, had there been no insurrection, there would have been no need to arrest insurrectionists, raise an army to suppress the insurrection, and emancipate the slaves in Confederate-held territory as a war measure. (More on the scope of the Emancipation Proclamation later.)

The other problem, of course, is that there is no shortage of primary source documents from the Confederate governments themselves stating exactly why they seceded. These documents are occasionally selectively quoted, but not often, since the discerning Confederate apologist realizes that quoting from one invites the reader to find the rest of the declaration, which utterly destroys the secession-as-proof-of-tyranny argument.

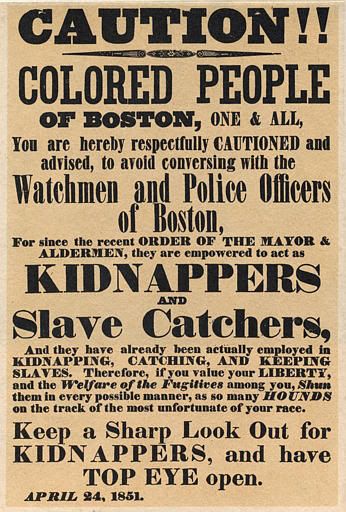

Common quotations used to argue that secession was prompted by northern tyranny and aggression are:

However, a summary reading of the full text quickly shows that the "property" referenced in the first paragraph was, in fact, slaves, and that the bulk of the document is dedicated to railing against abolitionist sentiment.

South Carolina also chimes in, with this gem.

Of course, the statutes referred to all involved the treatment of escaped slaves.

And most egregiously, Mississippi:

Wrong.

At least not the "tyranny" so often complained about in the modern day. Here's what it is they saw:

And just to give the "escaping tyranny" falsehood its death-blow, here is an excerpt from an address given by Alexander Stephens, member of Georgia's secession convention (where he argued against seceding on the grounds that the Union would militarily crush the South) and vice president of the Confederate States of America:

Ah, but regardless of their reasons, moral or immoral, it was the right of the states to end the compact of the Constitution, cries out the Libertarian circle! It was never the intention of the Founders to forever bind the states against their wills, and they intentionally left the door open to secession by not explicitly banning it in the Constitution! Lincoln's actions, therefore, forever and improperly removed a natural right of the states, a safeguard against future tyranny.

Well, no. Let's look at the intentions of the Founders. Secession did indeed occur to them; after all, many were still alive during the Nullification Crisis of the 1830s. There are therefore many writings from several Founding Fathers to draw from. At random, let's start with James Madison. From this letter to William Rives.

And now for the thoughts of the man commonly referred to as the father of our country, George Washington, chairman of the Constitutional Convention and first President. This is from his Circular to the States.

Well, if Washington wouldn't support dissolving the Union, then surely Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, that man who more than any other spurred the sundering of the American colonies from British rule, who called for regular revolutions to avoid tyranny, would!

Hate to disappoint, but...

Now, none of this is to say that the North was all sweetness and light. It was not. While slavery was the proximate cause of the initial secessions, and therefore the ultimate cause of the war, freeing the slaves was not the North's motive in prosecuting the war. Rather, the North was motivated primarily to preserve the Union; while Lincoln was personally an abolitionist, he did not believe it within his power as President to free the slaves. (Ironic, since he did take several powers normally reserved for Congress - namely, suspension of habeus corpus and calling out the militia to suppress insurrection - upon himself.)

The Emancipation Proclamation was indeed a great step, but it was first and foremost a war measure. Slave states which did not secede from the Union were permitted to keep their slaves until the passage of the 13th Amendment. In fact, prior to the Proclamation, Lincoln rescinded orders by General John Frémont and General David Hunter freeing the slaves in areas of the Confederacy they had captured; he dismissed Frémont when the general refused the President's orders to reverse his decision.

It was political reality that making the war about slavery would likely have cost Lincoln the war (Ulysses S. Grant said he would resign if he thought the war's objective was to free the slaves, and the border states would likely have simply seceded themselves), but that doesn't change the fact that the Union's prosecution of the war was not to free the slaves; it just makes it more excusable.

However, what is not excusable is the South's behavior prior to and during the Civil War. The initial secessions were without doubt motivated by a desire to continue chattel slavery (secessions after Lincoln took office were motivated by an unwillingness to contribute troops to fight the South, but again, without slavery none of it would have happened), and that is what matters to the causes of the war.

I apologize if some of this essay seems incoherent; it was written in one draft in the post form. I may revise it at a later time.

In this thread, I'm going to lay out the facts as I see them. I freely admit to being a Unionist and ardent anti-Confederate, but feel that these are positions borne out by the objective facts of the matter rather than damaging biases. Make of that what you will.

First, the motives behind secession.

Too often, you will see apologists for the Confederacy claiming that the South did what it did because they saw that Abraham Lincoln was a despotic tyrant in the making, that he would subjugate the rights of the people and crush the states beneath the boot of the federal government. "Lincoln the Tyrant" is a popular trope, spurred onward by the usual grain of truth that gives such things their lasting appeal: Abraham Lincoln did, as President, suspend habeas corpus, raise an army without the consent of Congress, and, yes, ordered the forfeit of property on the part of Confederates (i.e. freed the slaves, though it's not often put like that in a criticism for obvious reasons). You see this repeated over and over in neo-Confederate and anarchocapitalist circles; for instance, a look through the titles of Thomas DiLorenzo's essays shows an obsession with writing extensive character attacks on President Lincoln, and while probably the most prolific, he's not the only one.

There are obvious problems with this approach, however. The most glaring is that none of the things that Lincoln did that earn so much scorn could have been done outside the context of the Civil War. In other words, far from predicting Lincoln's behavior and seceding to avoid it, the southern states were the catalyst for his behavior! After all, had there been no insurrection, there would have been no need to arrest insurrectionists, raise an army to suppress the insurrection, and emancipate the slaves in Confederate-held territory as a war measure. (More on the scope of the Emancipation Proclamation later.)

The other problem, of course, is that there is no shortage of primary source documents from the Confederate governments themselves stating exactly why they seceded. These documents are occasionally selectively quoted, but not often, since the discerning Confederate apologist realizes that quoting from one invites the reader to find the rest of the declaration, which utterly destroys the secession-as-proof-of-tyranny argument.

Common quotations used to argue that secession was prompted by northern tyranny and aggression are:

Well, here we have Texas accusing the federal government of incompetence and dereliction of duty in defending its territory. Seems a reasonable complaint, doesn't it? After all, if the federal government were truly remiss in its duties in defending its territory, then Texas, having once been a sovereign republic itself and having agreed to become one of the United States presumably with the assumption that it would be defended, might actually have legitimate cause to question continuing as part of the Union.Texas Declaration of Causes wrote:By the disloyalty of the Northern States and their citizens and the imbecility of the Federal Government, infamous combinations of incendiaries and outlaws have been permitted in those States and the common territory of Kansas to trample upon the federal laws, to war upon the lives and property of Southern citizens in that territory, and finally, by violence and mob law, to usurp the possession of the same as exclusively the property of the Northern States.

The Federal Government, while but partially under the control of these our unnatural and sectional enemies, has for years almost entirely failed to protect the lives and property of the people of Texas against the Indian savages on our border, and more recently against the murderous forays of banditti from the neighboring territory of Mexico; and when our State government has expended large amounts for such purpose, the Federal Government has refuse reimbursement therefor, thus rendering our condition more insecure and harassing than it was during the existence of the Republic of Texas.

These and other wrongs we have patiently borne in the vain hope that a returning sense of justice and humanity would induce a different course of administration.

However, a summary reading of the full text quickly shows that the "property" referenced in the first paragraph was, in fact, slaves, and that the bulk of the document is dedicated to railing against abolitionist sentiment.

South Carolina also chimes in, with this gem.

A noble sentiment; after all, if several parties to an agreement are flouting that agreement with abandon, why continue it?South Carolina Declaration of Causes wrote:We hold that the Government thus established is subject to the two great principles asserted in the Declaration of Independence; and we hold further, that the mode of its formation subjects it to a third fundamental principle, namely: the law of compact. We maintain that in every compact between two or more parties, the obligation is mutual; that the failure of one of the contracting parties to perform a material part of the agreement, entirely releases the obligation of the other; and that where no arbiter is provided, each party is remitted to his own judgment to determine the fact of failure, with all its consequences.

In the present case, that fact is established with certainty. We assert that fourteen of the States have deliberately refused, for years past, to fulfill their constitutional obligations, and we refer to their own Statutes for the proof.

Of course, the statutes referred to all involved the treatment of escaped slaves.

And most egregiously, Mississippi:

So, assuredly they saw Lincoln's tyranny coming, with a statement such as that, right?Mississippi Declaration of Causes wrote:Utter subjugation awaits us in the Union, if we should consent longer to remain in it. It is not a matter of choice, but of necessity.

Wrong.

At least not the "tyranny" so often complained about in the modern day. Here's what it is they saw:

Source.In the momentous step which our State has taken of dissolving its connection with the government of which we so long formed a part, it is but just that we should declare the prominent reasons which have induced our course.

Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery-- the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun. These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization. That blow has been long aimed at the institution, and was at the point of reaching its consummation. There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin.

And just to give the "escaping tyranny" falsehood its death-blow, here is an excerpt from an address given by Alexander Stephens, member of Georgia's secession convention (where he argued against seceding on the grounds that the Union would militarily crush the South) and vice president of the Confederate States of America:

From the Cornerstone Address. And to expand further on it, the following is from a post-war entry in Stephens' diary:But not to be tedious in enumerating the numerous changes for the better, allow me to allude to one other-though last, not least: the new Constitution has put at rest forever all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institutions-African slavery as it exists among us-the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution. Jefferson, in his forecast, had anticipated this, as the "rock upon which the old Union would split." He was right. What was conjecture with him, is now a realized fact. But whether he fully comprehended the great truth upon which that rock stood and stands, may be doubted. The prevailing ideas entertained by him and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old Constitution were, that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally and politically. It was an evil they knew not well how to deal with; but the general opinion of the men of that day was, that, somehow or other, in the order of Providence, the institution would be evanescent and pass away. This idea, though not incorporated in the Constitution, was the prevailing idea at the time. The Constitution, it is true, secured every essential guarantee to the institution while it should last, and hence no argument can be justly used against the constitutional guarantees thus secured, because of the common sentiment of the day. Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error. It was a sandy foundation, and the idea of a Government built upon it-when the "storm came and the wind blew, it fell."

So, I should think that this lays to rest claims that the southern states were benevolently attempting to avoid general oppression; they rather acted in order to keep a large segment of their own populations oppressed.Slavery was without doubt the occasion of secession; out of it rose the breach of compact, for instance, on the part of several Northern States in refusing to comply with Constitutional obligations as to rendition of fugitives from service, a course betraying total disregard for all constitutional barriers and guarantees.

Ah, but regardless of their reasons, moral or immoral, it was the right of the states to end the compact of the Constitution, cries out the Libertarian circle! It was never the intention of the Founders to forever bind the states against their wills, and they intentionally left the door open to secession by not explicitly banning it in the Constitution! Lincoln's actions, therefore, forever and improperly removed a natural right of the states, a safeguard against future tyranny.

Well, no. Let's look at the intentions of the Founders. Secession did indeed occur to them; after all, many were still alive during the Nullification Crisis of the 1830s. There are therefore many writings from several Founding Fathers to draw from. At random, let's start with James Madison. From this letter to William Rives.

Madison actually considered the idea of secession so preposterous that until it actually came up when South Carolina first threatened it he felt there was no need to even mention it, and was astonished that he should have to. He also references the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution as proof positive that the states had no such ability, something that modern neo-Confederates tend to deny. Given that he wrote the thing, I should think I trust Madison's interpretation of it.The milliners it appears, endeavor to shelter themselves under a distinction between a delegation and a surrender of powers. But if the powers be attributes of sovereignty & nationality & the grant of them be perpetual, as is necessarily implied, where not otherwise expressed, sovereignty & nationality according to the extent of the grant are effectually transferred by it, and a dispute about the name, is but a battle of words. The practical result is not indeed left to argument or inference. The words of the Constitution are explicit that the Constitution & laws of the U. S. shall be supreme over the Constitution & laws of the several States, supreme in their exposition and execution as well as in their authority. Without a supremacy in those respects it would be like a scabbard in the hand of a soldier without a sword in it. The imagination itself is startled at the idea of twenty four independent expounders of a rule that cannot exist, but in a meaning and operation, the same for all.

The conduct of S. Carolina has called forth not only the question of nullification, but the more formidable one of secession. It is asked whether a State by resuming the sovereign form in which it entered the Union, may not of right withdraw from it at will. As this is a simple question whether a State, more than an individual, has a right to violate its engagements, it would seem that it might be safely left to answer itself. But the countenance given to the claim shows that it cannot be so lightly dismissed. The natural feelings which laudably attach the people composing a State, to its authority and importance, are at present too much excited by the unnatural feelings, with which they have been inspired agst their brethren of other States, not to expose them, to the danger of being misled into erroneous views of the nature of the Union and the interest they have in it. One thing at least seems to be too clear to be questioned, that whilst a State remains within the Union it cannot withdraw its citizens from the operation of the Constitution & laws of the Union. In the event of an actual secession without the Consent of the Co States, the course to be pursued by these involves questions painful in the discussion of them.

And now for the thoughts of the man commonly referred to as the father of our country, George Washington, chairman of the Constitutional Convention and first President. This is from his Circular to the States.

Ouch. That one's got to sting, especially since many neo-Confederates actually hold Washington as a hero. There was in fact a portrait of him dominating the front wall of the hall in Montgomery where the Confederate Constitution was drawn up.There are four things, which I humbly conceive, are essential to the well being, I may even venture to say, to the existence of the United States as an Independent Power:

1st. An indissoluble Union of the States under one Federal Head.

2dly. A Sacred regard to Public Justice.

3dly. The adoption of a proper Peace Establishment, and

4thly. The prevalence of that pacific and friendly Disposition, among the People of the United States, which will induce them to forget their local prejudices and policies, to make those mutual concessions which are requisite to the general prosperity, and in some instances, to sacrifice their individual advantages to the interest of the Community.

<snip>

Under the first head, altho' it may not be necessary or proper for me in this place to enter into a particular disquisition of the principles of the Union, and to take up the great question which has been frequently agitated, whether it be expedient and requisite for the States to delegate a larger proportion of Power to Congress, or not, Yet it will be a part of my duty, and that of every true Patriot, to assert without reserve, and to insist upon the following positions, That unless the States will suffer Congress to exercise those prerogatives, they are undoubtedly invested with by the Constitution, every thing must very rapidly tend to Anarchy and confusion, That it is indispensable to the happiness of the individual States, that there should be lodged somewhere, a Supreme Power to regulate and govern the general concerns of the Confederated Republic, without which the Union cannot be of long duration. That there must be a faithful and pointed compliance on the part of every State, with the late proposals and demands of Congress, or the most fatal consequences will ensue, That whatever measures have a tendency to dissolve the Union, or contribute to violate or lessen the Sovereign Authority, ought to be considered as hostile to the Liberty and Independency of America, and the Authors of them treated accordingly, and lastly, that unless we can be enabled by the concurrence of the States, to participate of the fruits of the Revolution, and enjoy the essential benefits of Civil Society, under a form of Government so free and uncorrupted, so happily guarded against the danger of oppression, as has been devised and adopted by the Articles of Confederation, it will be a subject of regret, that so much blood and treasure have been lavished for no purpose, that so many sufferings have been encountered without a compensation, and that so many sacrifices have been made in vain.

Well, if Washington wouldn't support dissolving the Union, then surely Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, that man who more than any other spurred the sundering of the American colonies from British rule, who called for regular revolutions to avoid tyranny, would!

Hate to disappoint, but...

And in another letter, this one addressed to a third party and talking about a discussion Jefferson had had with Washington that day:Thomas Jefferson to George Washington, 1794 wrote:I can scarcely contemplate a more incalculable evil than the breaking of the union into two or more parts.

But... but... Whether they intended it or not, secession isn't disallowed in the Constitution, and the 9th and 10th amendments allow the states to do things that they aren't specifically barred from doing, one might say. And for that, we turn to the Constitution itself. You may recall Madison's letter bringing this up.That with respect to the existing causes of uneasiness, he thought there were suspicions against a particular party, which had been carried a great deal too far; there might be desires, but he did not believe there were designs to change the form of government into a monarchy; that there might be a few who wished it in the higher walks of life, particularly in the great cities, but that the main body of the people in the eastern States were as steadily for republicanism as in the southern. That the pieces lately published, and particularly in Freneau's paper, seemed to have in view the exciting opposition to the government. That this had taken place in Pennsylvania as to the Excise law, according to information he had received from General Hand. That they tended to produce a separation of the Union, the most dreadful of all calamities, and that whatever tended to produce anarchy, tended, of course, to produce a resort to monarchical government.

Insurrection and rebellion are obviously illegal; otherwise there would be no provision for suppressing it.United States Constitution, Article 1, Section 8, Clause 15 wrote:To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions

Again, if rebellion is legal, why the injunction against it?United States Constitution, Article 1, Section 9, Clause 2 wrote:The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.

Again, if you need the consent of Congress to raise an army, then it would seem that just leaving would be out; after all, if you can just leave, why bother having such a restriction?United States Constitution, Article 1, Section 10, Clause 3 wrote:No State shall, without the Consent of Congress, lay any Duty of Tonnage, keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace, enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State, or with a foreign Power, or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay.

Speaks for itself, I think.United States Constitution, Article 3, Section 3 wrote:Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort.

This one's the kicker. When taken in the context of the Supremacy Clause, we see that the states cannot violate the territorial sovereignty of the United States. Secession is such a violation. Here is that Clause, which is the one Madison referred to in his letter to Senator Rives:United States Constitution, Article 4, Section 3, Clause 2 wrote:The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States; and nothing in this Constitution shall be so construed as to Prejudice any Claims of the United States, or of any particular State.

So where is the right to secede? I'm certainly not seeing it. Incidentally, if that was such a big deal to the Confederate States, you would think they would have seen fit to include it in their own constitution. They did not. In fact, the only change they made which affects the ability of states to leave their union is this:United States Constitution, Article 6, Clause 2 wrote:This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

So much for the right of secession.Confederate Constitution, Preamble wrote:We, the people of the Confederate States, each State acting in its sovereign and independent character, in order to form a permanent federal government, establish justice, insure domestic tranquillity, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity...

Now, none of this is to say that the North was all sweetness and light. It was not. While slavery was the proximate cause of the initial secessions, and therefore the ultimate cause of the war, freeing the slaves was not the North's motive in prosecuting the war. Rather, the North was motivated primarily to preserve the Union; while Lincoln was personally an abolitionist, he did not believe it within his power as President to free the slaves. (Ironic, since he did take several powers normally reserved for Congress - namely, suspension of habeus corpus and calling out the militia to suppress insurrection - upon himself.)

The Emancipation Proclamation was indeed a great step, but it was first and foremost a war measure. Slave states which did not secede from the Union were permitted to keep their slaves until the passage of the 13th Amendment. In fact, prior to the Proclamation, Lincoln rescinded orders by General John Frémont and General David Hunter freeing the slaves in areas of the Confederacy they had captured; he dismissed Frémont when the general refused the President's orders to reverse his decision.

It was political reality that making the war about slavery would likely have cost Lincoln the war (Ulysses S. Grant said he would resign if he thought the war's objective was to free the slaves, and the border states would likely have simply seceded themselves), but that doesn't change the fact that the Union's prosecution of the war was not to free the slaves; it just makes it more excusable.

However, what is not excusable is the South's behavior prior to and during the Civil War. The initial secessions were without doubt motivated by a desire to continue chattel slavery (secessions after Lincoln took office were motivated by an unwillingness to contribute troops to fight the South, but again, without slavery none of it would have happened), and that is what matters to the causes of the war.

I apologize if some of this essay seems incoherent; it was written in one draft in the post form. I may revise it at a later time.