A recent CNN

article:

In a normal oil market, the cost of producing the last, most expensive barrel of oil needed to satisfy worldwide demand sets the price for every barrel the world over. Other auction commodity markets work much the same way.

So even if Saudi Arabia produces at $4 a barrel, if the final, multi-millionth barrel required to heat houses and run cars costs $50, and is produced, for argument's sake, at a flagging field in West Texas, the world price is $50. That's what economists call the equilibrium price: It's where the price that customers are willing to pay meets the production cost, including a cushion, naturally, for profit or "the cost of capital."

But today, the sudden surge in demand and the production bottlenecks have thrown the market radically out of balance.[...]

A big swath of the market isn't really paying that $125 a barrel number you hear about seemingly every hour. In China, India and the Middle East, governments are heavily subsidizing oil for their consumers and corporations, leading to rampant over-consumption - and driving up prices even more. [...]

So what does that barrel cost today? According to Stephen Brown, an economist at the Dallas Federal Reserve, that final barrel costs just $50 to produce.

When supply lags behind increase in desired demand, there isn't as much production as everyone wants. Prices get really high as consumers bid for the limited amount available, and it is possible for an oil-exporting nation or company to sell oil for vastly greater than the cost of production, getting record profits in the process.

------------

Within this context, there would be the effect of speculation and other such economic factors on causing oil price rise to accelerate.

For a few weeks now, observers have noticed that Iran is leasing tankers and storing oil in them. At about $140,000 a week or so, that is expensive storage.[...]

"It is not just Iran. Today we started checking on how many tankers Iran had, and soon discovered that there is a serious tanker shortage. Lease prices have soared in the past few weeks. It is clear there are a lot of speculators betting that oil is going to rise to $150 or so and are willing to pay very high prices for keeping the oil on the seas waiting for higher prices. It is a speculative boom."

He then told me about flying into New York in the early '80s. Outside the harbor were 30 or so tankers just sitting, waiting for prices to continue to increase as they had been doing for some time. When they did not, they all tried to get into the harbor at the same time, and of course they couldn't.

From here.

For example, with the recent rate of oil prices rise, waiting even days to weeks to sell oil can mean getting a number of dollars more per barrel than if selling it at once. The effect of intentionally limiting oil sales in the near-term would be to push prices higher.

The recent gain from investment and speculation with oil is enormous. For most investments, like the average stock, a few percent increase per year is good, yet, in the case of oil, the selling price value increased by tens of percent in a matter of months, and that attracts a lot of interest.

Index speculators have gone from investing $13+ billion in 2003 to $260+ billion in commodities at

the end of March of this year.

------------

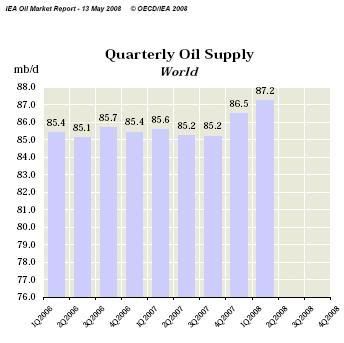

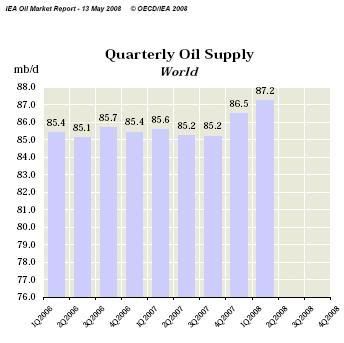

Enormous rise in oil prices has been occurring even while the total supply of oil and oil-equivalents has been slightly going up on a quarterly basis. It was

on average 87.2 million barrels per day in the first quarter of 2008, compared to 86.5 mbd/day in the last quarter of 2007, although it goes up and down from month to month such as more recently 86.6 mbd/day in May versus 86.8 mbd/day in April.

Overall, 2007 production was 85.6 mbd/day compared to 83.4 mbd/day in 2004.

One major factor in oil price rise can be when such a slow growth in production does not meet the increase rate in desired demand, including from rapidly-growing economies like China. Demand is relatively inelastic, making small change in supply versus desired demand cause a large change in price, since it takes many percent increase in price to reduce the average consumer's consumption by 1% ... or, in some cases, even to just slightly slow growth in the consumption of some consumers.

The overall change in production has followed the trend that has been occurring for a number of years, in which some segments of the conventional crude supply decline while production from some other sources increases.

For example, natural gas to liquids (NGL) production has gone up, e.g. "OPEC condensate and gas liquids supply, not included in non-OPEC totals, reaches 5.2 mb/d this year, up [by 8%] from 4.8 mb/d in 2007"

(IEA, May 2008).

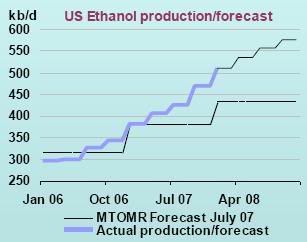

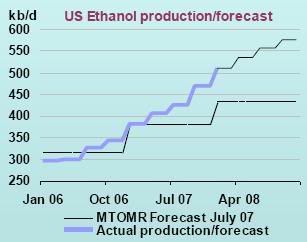

Of course, increasing production of oil-equivalents such as coal-to-liquids (CTL), NGLs, biofuels, etc. can have a greater effect on the price of gasoline than a weaker and more indirect effect on the price of crude oil itself.

Indeed, such is one of the contributing factors to why the ~ 150% (~ $1.60/gallon -> $4.04/gallon) in U.S. gasoline prices between 2004 and now has been so much less than the ~ 370% rise in

the crude oil prices (~ $30/barrel -> $140/barrel) over the same time period. (Other factors include a base expense of up to several tens of cents per gallon of average taxes in the U.S., plus the cost of converting oil to gasoline at refineries ... beyond the price of the inputs alone).

It seems strange to talk about 150% price rise in gasoline as less, but that is relative to the 370% price rise in crude oil itself. Increasing production of alternative fuel is one factor helping motor fuel costs be influenced by more than crude oil prices alone, but the limited rate of production increase hasn't been enough to prevent price rise.

------------

Some major factors leading to the increase in the price of oil are:

- Historical slow net increase in the total production of oil and oil-equivalents is less than the increase rate of desired demand, including rapidly growing economies such as China. Although alternative fuel and unconventional production is increasing, production is meanwhile declining from some segments of the conventional crude supply.

- The value of the dollar has greatly declined, contributing to further increasing the cost of oil measured in U.S. dollars; for example, in 2002, it took $0.94 to buy 1 euro of goods, but now it takes $1.55.

- The enormous financial incentive for speculation and for limiting the near-term supply of oil to make more profit selling it later at higher prices is another contribution.

Naturally, such factors are not mutually exclusive but have a combined effect greater than any single one alone.