Link

This was from the opinion section but seems to have been taken to the floor.

The Insanity of Drive-55 Laws

By STEPHEN MOORE

July 24, 2008; Page A15

It didn't seem possible that politicians could think up a sillier energy proposal than Barack Obama's windfall profits tax on oil companies, but Republican Sen. John Warner of Virginia has done just that.

Earlier this month, Mr. Warner suggested a return to the federal 55-mile-per-hour speed limit on America's highways, as a way to save on national gasoline consumption. "I drive over 55 miles an hour, . . . sometimes 65," he said on the Senate floor. "But I am willing to give up whatever advantage to me to drive at those speeds with the fervent hope that modest sacrifice on my part will help those people across this land . . . dealing with this financial crisis."

Meanwhile, environmental groups across the country are also pushing a lower national speed limit to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The notion here is that if people simply lift the pedal off the metal on the highways, they will help avert an environmental apocalypse.

Mr. Warner may be willing to drive slower to save gas. The vast majority of Americans surely are not. The original 55 mph speed-limit law, enacted in October 1974 after the OPEC oil embargo as a way to save energy, was probably the most despised and universally disobeyed law in America since Prohibition. In wide-open western states, driving at 70 mph or even 80 mph on miles upon miles of straight, flat, uncongested freeways is regarded as a God-given right. In the 1970s and '80s, the federal speed limit was a daily reminder of the intrusiveness of nanny-state regulation.

States were bullied into complying. If they didn't, they risked losing federal highway money -- which came from the gas taxes paid in part by their own residents. The law -- "double nickel," as it was called -- was so hated in Montana that the state legislature passed a law capping speeding tickets at $5. In Wyoming, the highway patrol told speeders to hold on to the tickets they issued because they were good for the whole day.

In 1995, the newly ascendant Republican Congress repealed the 55 mph limit. Most states acted quickly to allow speeds of up to 65 mph or even 75 mph on their interstates, and for good reason. As an energy saving policy, the double nickel was a bust. The National Motorists Association reports that about 95% of American drivers regularly exceeded the federal speed limit. Does it make sense to resurrect a law that 19 out of every 20 Americans disobeyed?

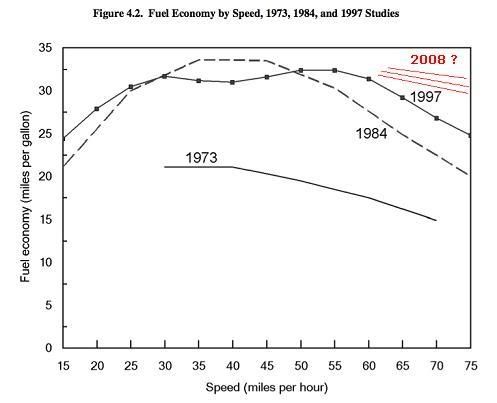

In the first few years when the law was strictly enforced, according to the Congressional Research Service, gasoline consumption was reduced by about 167,000 barrels a day. But over time the law was increasingly ignored, and average speeds on the highway fell by only a few miles per hour. The National Research Council estimated in 1984 that Americans spent one billion additional hours a year in their cars because of the speed limit law.

Mr. Warner repeats the myth that a lower federal speed limit will increase traffic safety. Back in 1995, Naderite groups argued that repealing the 55 mph limit would lead to "6,400 more deaths and millions more injuries" each year. In reality, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration data reveal that in the decade after speed limits went up (1995-2005), traffic fatalities fell by 17%, injuries by 33%, and crashes by 38%. That's especially significant because in 1995 far fewer drivers were gabbing on their cell phones or text messaging while driving.

In a study for the Cato Institute in 1999, I compared the fatality rates in states that raised their speed limits to 70 mph or more (mostly in the South or West) with those that didn't (mostly in the Northeast). There was little difference in safety. Of the 31 states that raised their speed limits to 70 mph or more, only two (the Dakotas) experienced a slight increase in highway deaths. The evidence is overwhelming that traffic safety is based less on how fast the traffic is going than on the variability in speeds that people are driving. The granny who drives 20 mph below the pace of traffic on the freeway is often as much a safety menace as the 20-year-old hot rodder.

Retail gasoline stores report that Americans have already reduced their gas purchases by about 5% this year -- presumably by driving less and buying more fuel-efficient cars. At $4.59 a gallon, motorists don't need to be lectured by politicians on the financial savings from cutting back. Those who want to stretch their dollars can drive 55 mph on their own (though they are well advised to stay in the right lane).

But many liberal and green do-gooders want the double nickel precisely because they want to force everyone to share in the sacrifice required. As an egalitarian friend once told me, he loves traffic jams because they are the ultimate form of democracy.

To the left, fairness means we all suffer equally together. In light of this alleged moral imperative, it doesn't matter if a lower speed limit means Americans would spend two billion extra hours on the road, or that, according to the Labor Department, assuming a $15 per hour average wage means the speed limit could cost the economy between $20 billion and $30 billion a year in lost output.

Calls for a 55 mph speed limit -- and for that matter most other government energy conservation plans, such as urging people to ride a bus or a bicycle rather than driving a car -- reflect a mindset that oil and gasoline are more valuable than human time.

But America is not running out of energy. We have potentially hundreds of years of oil and natural gas and coal supplies in America alone, if Congress would only let us drill for it. What is in short supply -- the only truly finite resource, as the late economist Julian Simon taught us -- is the time each of us spends on this earth. And most of us don't want to spend it sitting longer than we have to in traffic.

Mr. Moore is the senior economics writer for The Wall Street Journal editorial board.