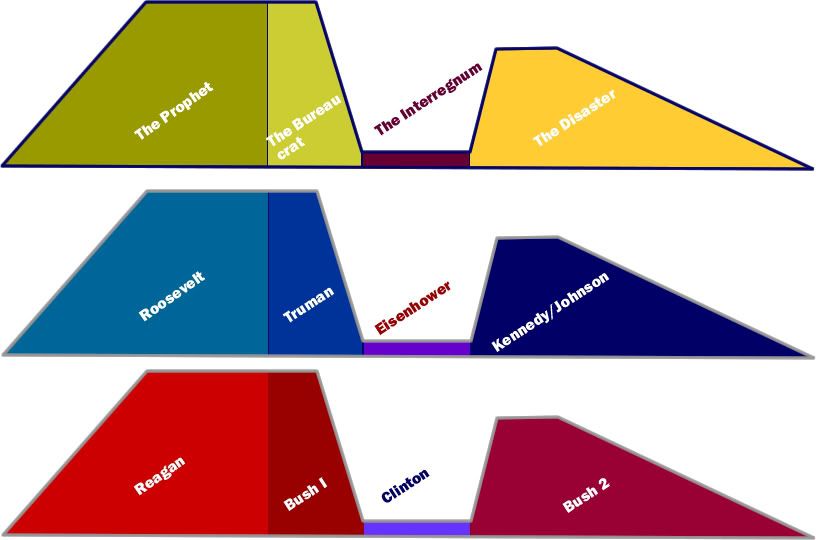

To simplify somewhat, this poster holds that political periods, at least in the modern era, are structured similarly: they are heralded in by a popular figure championing a new political paradigm (Roosevelt, Reagan), who are succeeded by a less popular and more 'mechanistic' figure with just enough effectiveness to continue to the old policies, but who is much more vulnerable to defeat (Truman, H.W. Bush); these 'bureaucrats' in turn find themselves displaced by moderate members of the opposition ideology (Eisenhower, Clinton), who themselves lead to a radicalization of the existing paradigm and its gradual dissolution (Johnson, W. Bush). And while there are certain elements in the two cycles of the twentieth century that differ from one another - Kennedy's role in the New Deal era has no corollary in our present Reaganist system - the similarities are there, I feel, and bear consideration.

The Prophet—The prophet comes to the scene with a completely new ideological approach to a stagnating problem. People attach themselves to the prophet affectively, and his (or her) key strength is communication. The prophet is able to package the ideological and structural changes such that ordinary people can not only understand it (in its own ideological space), but hook into some part of it, become affectively invested in it. The prophet will run over the opposition effectively on issues that would have been taboo even a few years before, largely because people have been primed communicatively for a general social transformation. The prophet will usually become an iconic figure within the ideological boundaries, and within the culture at large. The examples in the recent 30 year cycles are, of course, FDR and Reagan.

The Bureaucrat—The bureaucrat will usually be attached to the Prophet as a calmer and less radical figure, though he will share the ideological worldview of the prophet for the most part. He will be perceived as a less exalted continuation of the prophet, but it is precisely the lack of the affective investment that will sink the bureaucrat in the end. The bureaucrat will be perceived not as a transformational figure, but as a capable manager of a change that’s already taken place. But because he can’t inspire the sort of attachments that the prophet could, he will usually be doomed to a short reign, as the affective energy swings in the other direction. The examples in the recent 30 year cycles are Truman and Bush Senior.

The Interregnum—Because the affective attachments of the prophet waned during the reign of the bureaucrat, it really has nowhere else to go. It swirls around attaching itself to various secondary issues, though the bureaucrat may try to hook it into a war posture. As the reign of the bureaucrat comes to an end, then, you will often see deeply invested social conflicts (McCarthyism, the Culture Wars and L.A. Riots, etc.), as the affective energies once attached to the ideology gets set loose across the social landscape. This will lead to what i call the interregnum: the emergence of the other ideology within the 30 year cycle. In the case of the Roosevelt cycle, we see the emergence of Eisenhower. In the middle of the Reagan cycle, we see the emergence of Clinton. In both cases, the interregnum will be run by a relatively mild version of the second ideology, since the affective energies attached to the prophet have not completely disappeared. Because the interregnum will be relatively mild in terms of social transformation, it will almost always end in a painfully close election, since the distinction between the ideologies will seem less severe, and the middle group of undecideds will be unable to hook into one program or the other: Kennedy/Nixon; Bush/Gore.

The Disaster—As the ruling ideology endured the interregnum, it intensified its polarity as a matter of distinguishing itself from the mildness of the second ideology. When it gets into power after the interregnum, it throws this radicalization wholeheartedly at whatever social problems it perceives. For this reason, the Disaster is an amped up, highly volatile affective era, as we move from relative mildness in the distinction between ideologies to hard core distinction in the development of policy. In the first 30 year cycle, you thus get the rapid changes in civil rights laws and the war on poverty, while in the Bush 2 era you get the most extreme tilting toward neo-liberal economics, far beyond what Reagan could have dreamed of accomplishing. This radicality, moreover, will lead to the kind of social instability that makes war more probable, and pushes the ideology above any connection to reality. It thus leads to disaster for the ideology: the 60’s as the moment when the 30 year Democratic cycle became so radical that it could not sustain itself; the 00’s as the moment when Reaganism collapsed under the pressure of ideological purity.

So, if you’re smart, you should be asking the following: What about Nixon? In my view, Nixon/Ford/Carter were transition figures, placeholders as the electorate waited for a new cycle. The affective attachments of the period are confused, swaying from deep hatred and unmitigated love, to depression, and general ennui. They were, in short, unordered attachments. It’s not a mistake, I think, that the late 1960’s and early 1970’s were thus a period of structural readjustment in the economy and massive technological transformation of the society. The affective attachments, set loose from the mainstream ideologies, sunk themselves into all forms of economic and cultural production, actually collapsing the distinction between economy and culture in the process.

Now, you might be asking: are we in for another period of transition? Certainly, the economic factors would point to a situation nearly parallel to that of 1968: the dominant ideology has sunk the economy into a ideological black hole, perhaps requiring structural readjustment in the same way as the early 1970’s was the economic push of neo-liberalism that was only later cashed out as Reaganism.

The question in notions such as these, of course, is the placement of the Nixon-Ford-Carter years: it seems to upset the idea that political 'epochs' segue smoothly into each other. I am personally of the opinion that Nixon ought to have held the position of esteem among Republicans and conservatives generally that Reagan holds today; and while it's true that his economic policies were more liberal generally than Reagan's (and his support of liberal institutions like OSHA and the EPA certainly inveighs against his economic conservatism), it is certainly true that his rhetoric, his appeal to the 'Silent Majority', was the beginning of the end of the New Deal coalition. It seems to me that, had the Nixon Administration not ended in disgrace, that we'd have entered the conservative ('Reagan') cycle much sooner, with complete Republican dominance of Washington for the seventies, eighties, and most of the nineties, and we'd have entered a liberal re-alignment that much sooner.

If this is a valid way of looking at modern political history, then might it be possible to deduce a vague idea as to what the future has in store? If so, the question is, presuming - as now looks likely - that Obama is elected, what role will he play in the shifting of political sympathies? Will he be akin to Nixon, able to tap into a newly-emerging political alignment without being the direct benefactor of it, and actually delays its eventual victory over the opposing ideology? Or will he be more of a Reagan-figure, who directly leads to a resurgence of the newly dominant ideology?

There are parallels with both eras. Like Reagan, Obama's star seems to be ascending at the expense of a hugely unpopular incumbent President; but like Nixon he is running against a non-incumbent member of the dominant political party, who has largely subsumed the role of the President within the party (Johnson-Humphrey; Bush-McCain). Like Reagan, he has enormous charisma and has the ability to galvanize the masses, but again like Nixon, his proposed policies seem more pragmatic and remain located in the opposing (Reaganist) paradigm; just as Nixon was largely a moderate, Obama is more of a centrist than a traditional New Deal liberal, although like Nixon his rhetoric is relatively partisan.

Or perhaps this 'dialectical' mode of political history is bunk, and American politics really is more of a game of personalities than any back-and-forth swing of ideological sympathies. I'd be greatly interested in hearing the thoughts of the board on this matter.