http://crookedtimber.org/2011/08/05/pea ... years-ago/

I find this analysis straightforward and reasonably compelling. I think he's giving less weight to the relative importance of energy as a capital good than I would, but the framework within he's operating seems to me to be the best way of thinking about peak oil.Taking a break from my war with Murdochracy, my most recent column in the Australian Financial Review (over the fold) was about Peak Oil. Partly for tactical reasons, but also because I believe it’s correct in this case, I’m wearing my hardest neoclassical hat.

One of the more intriguing sidelights to debates over climate change and energy policy is the idea of Peak Oil. On the face of it, the Peak Oil hypothesis is a straightforward claim. The amount of oil generated by any given field follows a bell-shaped curve, first rising as the field is developed and then declining as the oil becomes harder and harder to pump.

The curve is referred to as the Hubbert curve, after US geologist M King Hubbert[1] who used it to predict the peak of US oil output around 1970. Applying Hubbert’s analysis to the world as a whole yielded the prediction that the global peak in oil production should be happening around now.

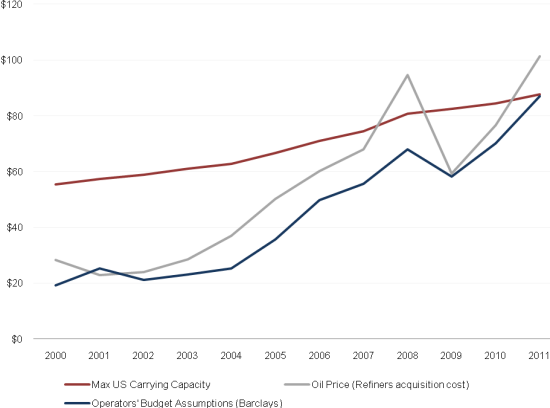

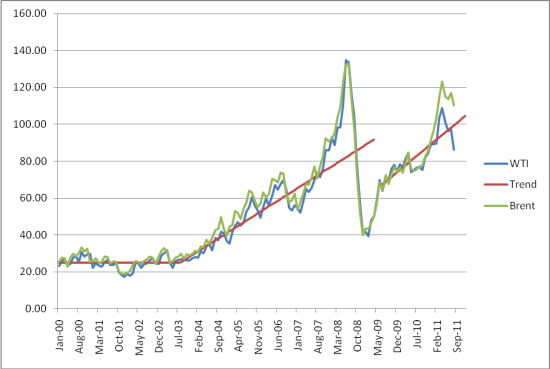

On the evidence available, the predictions of the Peak Oil hypothesis don’t look too bad. Despite near-record prices for oil, the output of crude oil has remained broadly constant for the last seven years. Such an apparent plateau is exactly what the Hubbert curve would predict, bearing in mind that commercial production began 150 years ago.

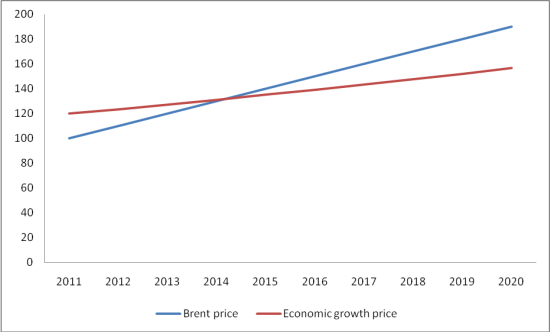

The economic effects of the depletion of oil resources will be mixed. Clearly, since underlying demand is rising with population and income growth, the price of oil must rise to clear the market. That’s good for suppliers of oil, as well as competing energy sources, and bad for consumers. Overall because of the unpriced negative effects of burning oil, the most important of which is the release of carbon dioxide, a reduction in oil output is beneficial for the planet as a whole.

This is all straightforward: economists have been analysing markets for exhaustible resources ever since the pioneering work of Harold Hotelling in the 1930s. The observed outcomes fit Hotelling’s model pretty well – rising real prices are needed to sustain an optimal extraction path.

But discussions around Peak Oil are dominated, not by economic analysis, but by a range of more or less apocalyptic scenarios. In these scenarios, an end to ever-growing output of oil means an end to industrial civilisation as we know it.

There are a number of misunderstandings here. A lot of discussion seems to assume that Peak Oil means an immediate end to oil production, when the Hubbert curve implies a gradual decline over 100 years or more.

More importantly, though, the Peak Oil story is about production. But, if oil is essential to modern civilisation, what matters is not production but consumption.

The Oil Peak that actually mattered was the peak in consumption per person, which took place back in 1980 at 5.3 barrels per person per year. Since then, consumption per person has dropped to 4.4 barrels per person per year. Given the growth of demand in Asia, consumption per person in the countries that were already rich in 1980 has fallen much faster. Meanwhile living standards have risen substantially[2], unconstrained by declining consumption per person of oil, and of energy more generally.

Oddly enough, most people who worry about Peak Oil are also environmentalists concerned about climate change. From this viewpoint, which I share, Peak Oil looks like good news rather than bad. But the optimistic interpretation is trumped by the spurious idea that there is a 1-1 relationship between oil (or energy) and economic activity. This fallacious idea is held both by Peak Oil fans and by the rightwing doomsayers who suggest that reducing emissions of CO2 will destroy the economy.

A particularly interesting subgroup of Peak Oil fans are those who see nuclear energy as the only possible solution, a view that was mooted by Hubbert himself. This part of the discussion is dominated by a belief in something called ‘baseload power demand’ which must be met at all times if disaster is to be avoided. The idea that demand responds to prices and market structures seems entirely foreign to this discussion.

One of the few upsides of the disastrous Fukushima meltdown is that it has allowed a perfect test of this theory. Following the meltdown, Japan has taken 38 of its 54 reactors offline. It’s now midsummer there, and the blackouts predicted by the scaremongers have not occurred. Instead, the reduction in supply has been handled by (mostly voluntary) efficiency measures.

Energy is important, but it is no more ‘essential’ or ‘special’ than many other goods and services in a modern economy. If the supply is reduced, the market will respond to bring demand into line, especially if this response is facilitated by sensible government policy. No single source or technology, such as oil, nuclear or solar is essential, although none should be dismissed out of hand.

fn1. A fascinating guy, by the way. He was associated with the Technocracy movement, which briefly in the 1930s looked like a serious contender as an alternative form of government for the US. Wikipedia has lots on this.

fn2. In the rich world as a whole, and in most of Asia. Those in the bottom half of the US income distribution and in some very poor countries haven’t done so well, but that has nothing to do with oil.