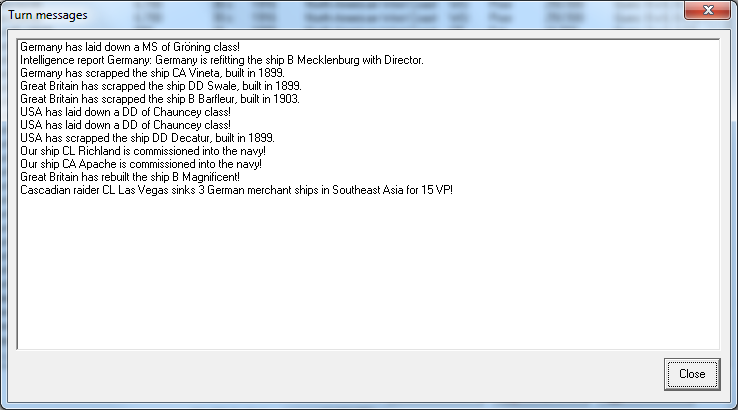

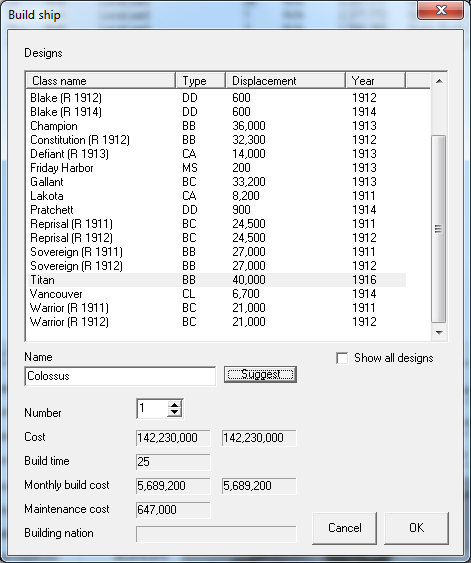

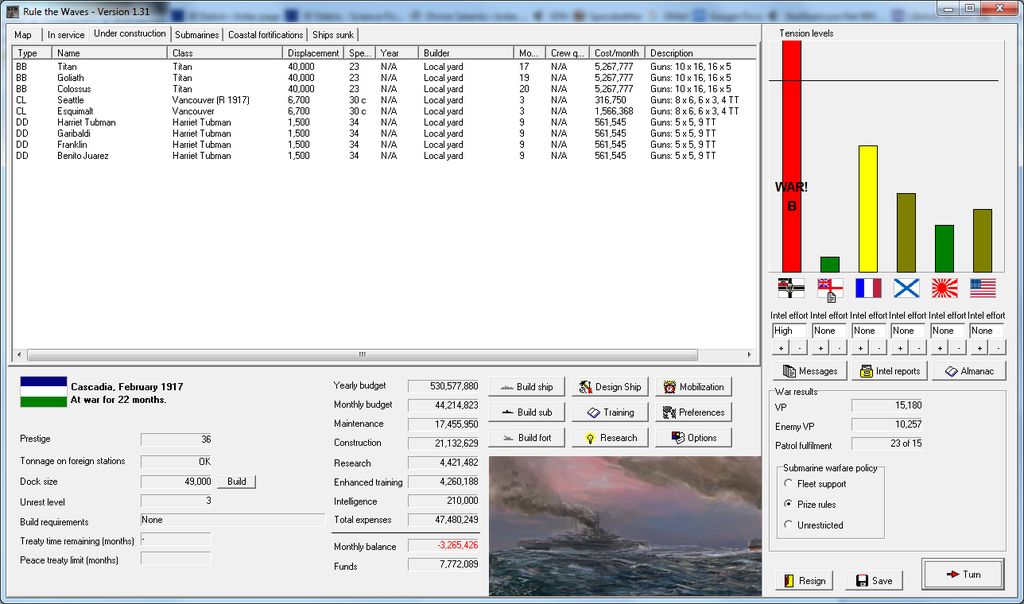

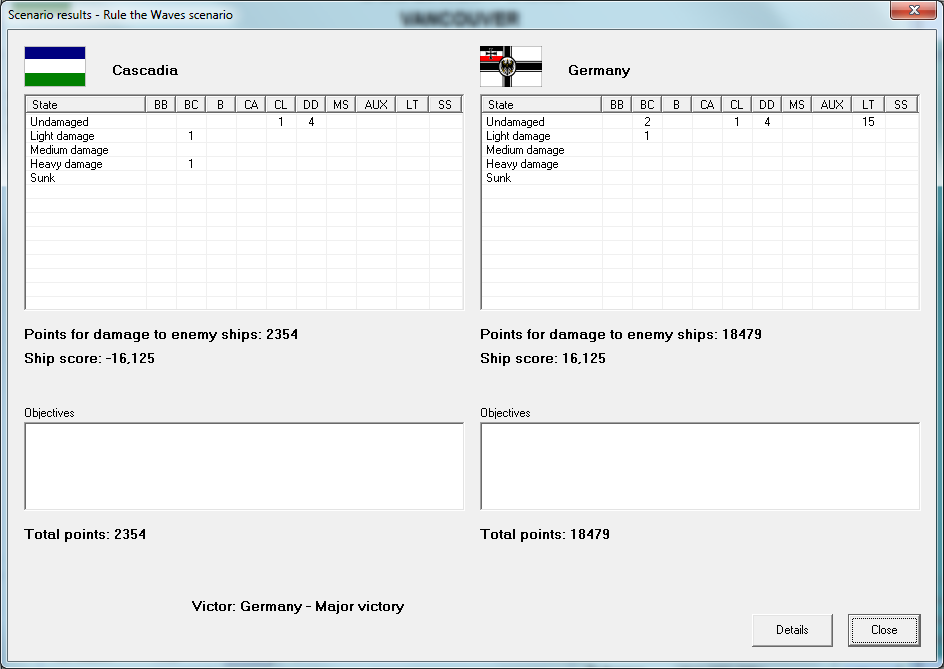

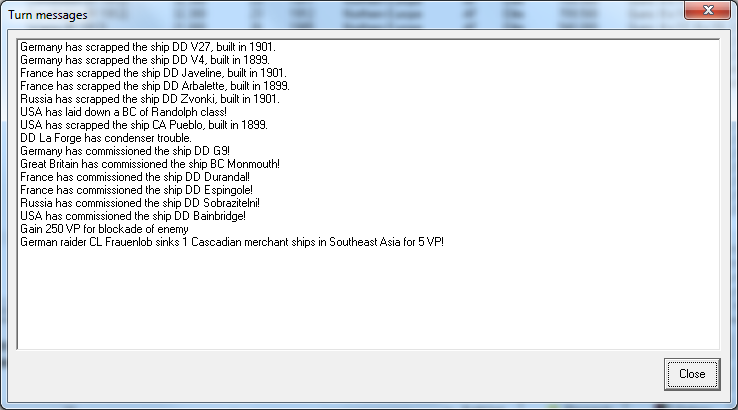

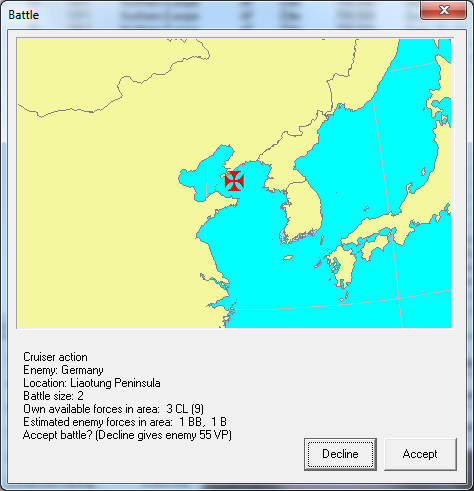

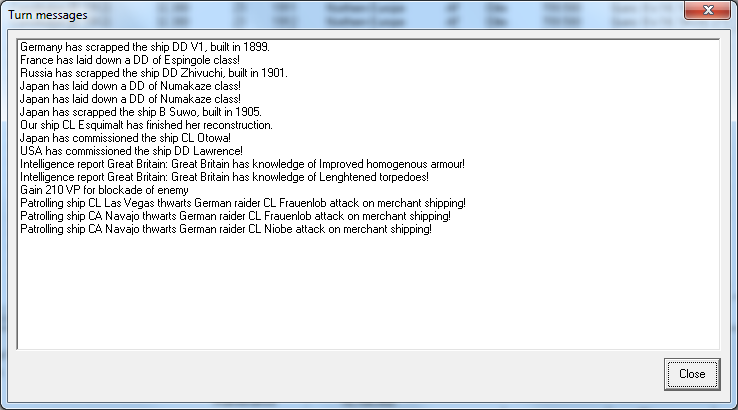

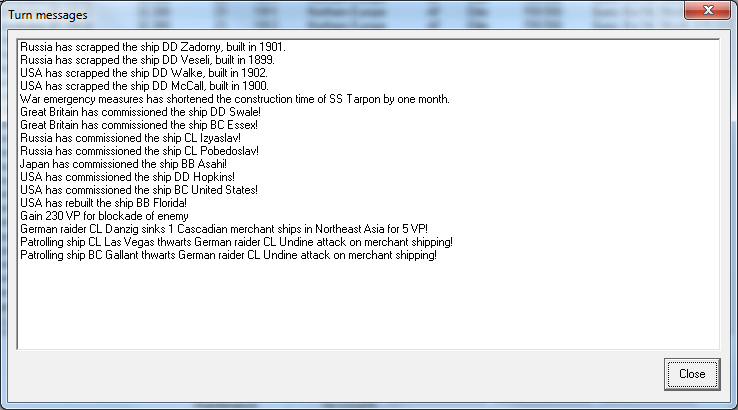

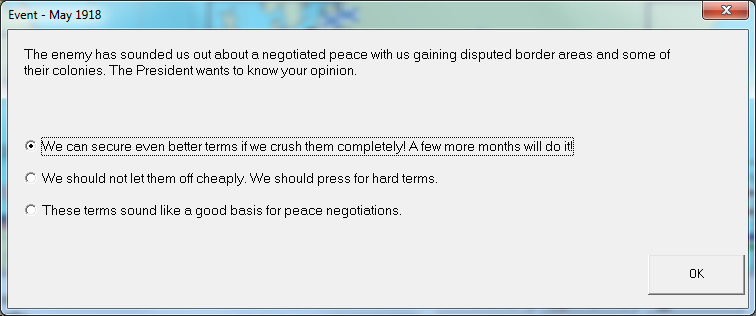

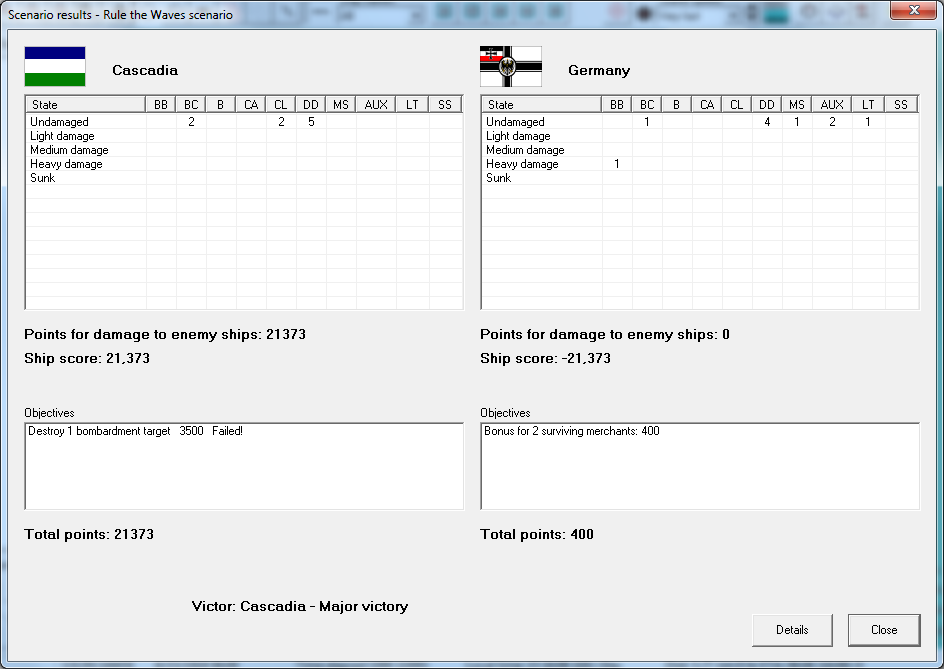

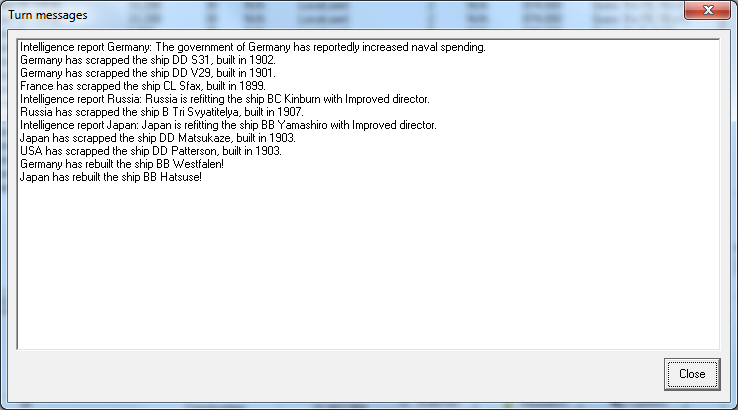

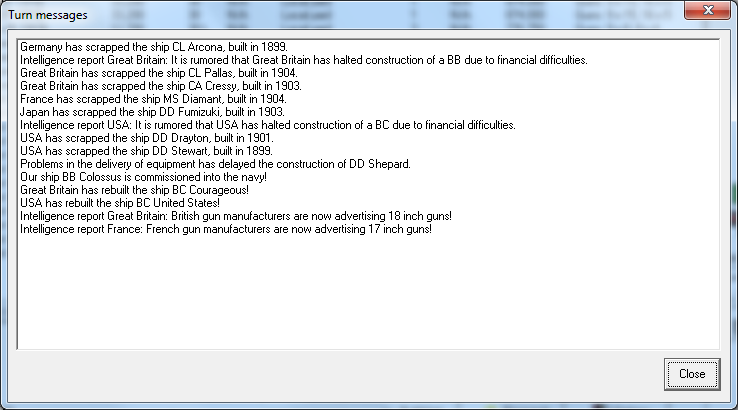

July 1918

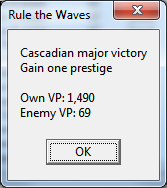

The

Titan was commissioned. With 10 16" guns as main armament, she was the most powerful warship afloat at that time.

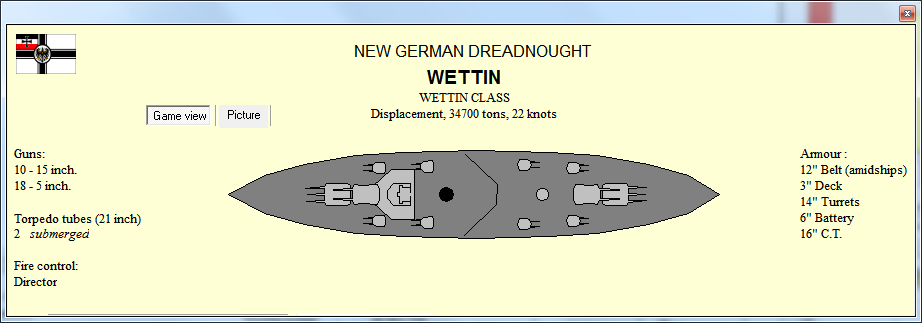

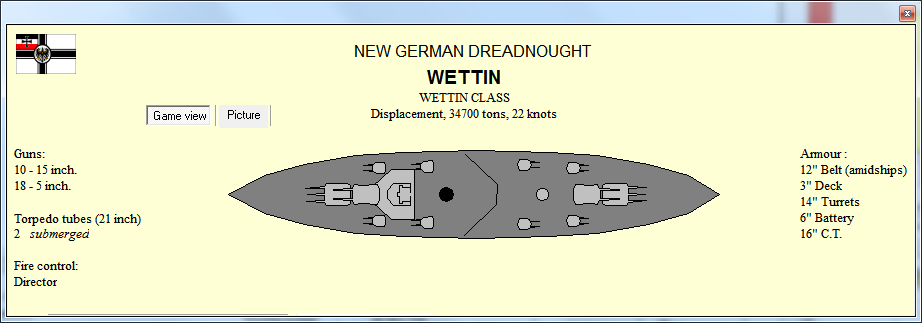

German blueprints for the

Wettin were acquired by agents.

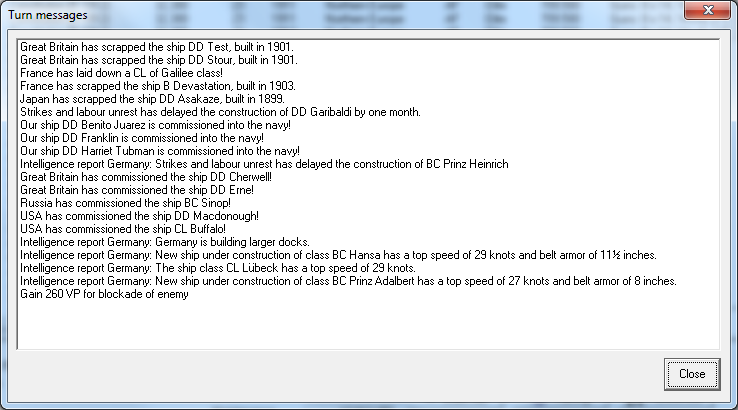

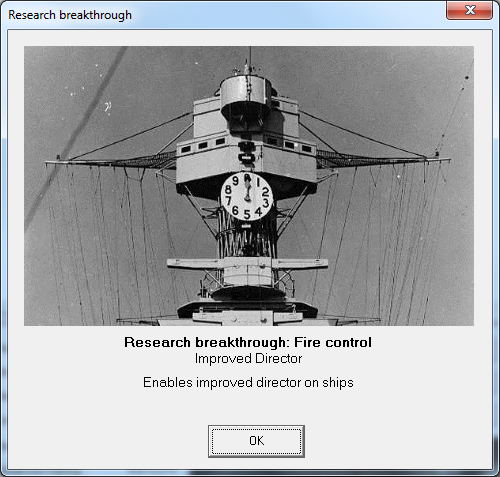

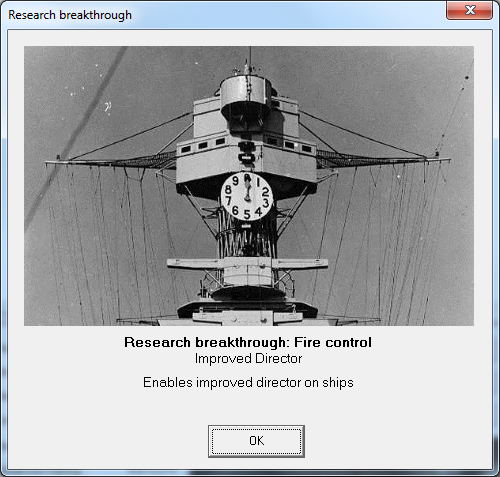

Technical teams with Naval Artillery informed Admiral Garrett that they had completed work on a new and improved director firing system.

Designers were finding progress on making new design calculations even more advanced than now being used.

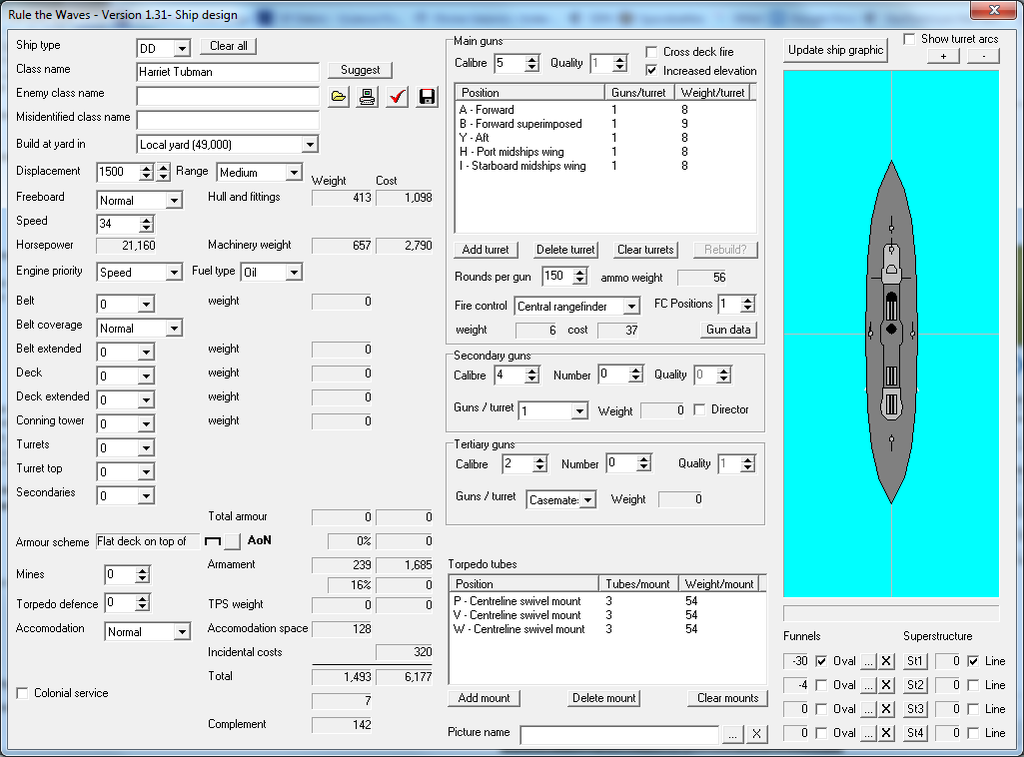

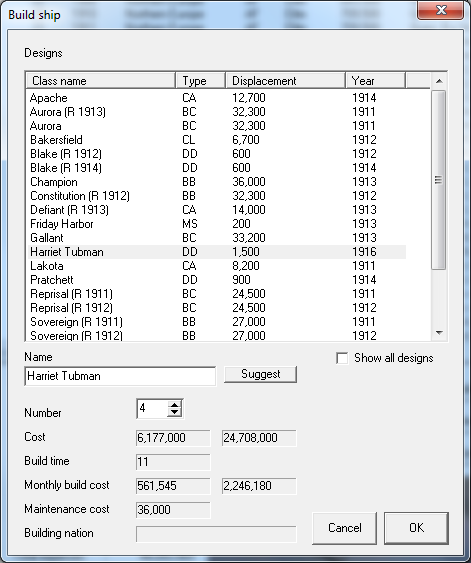

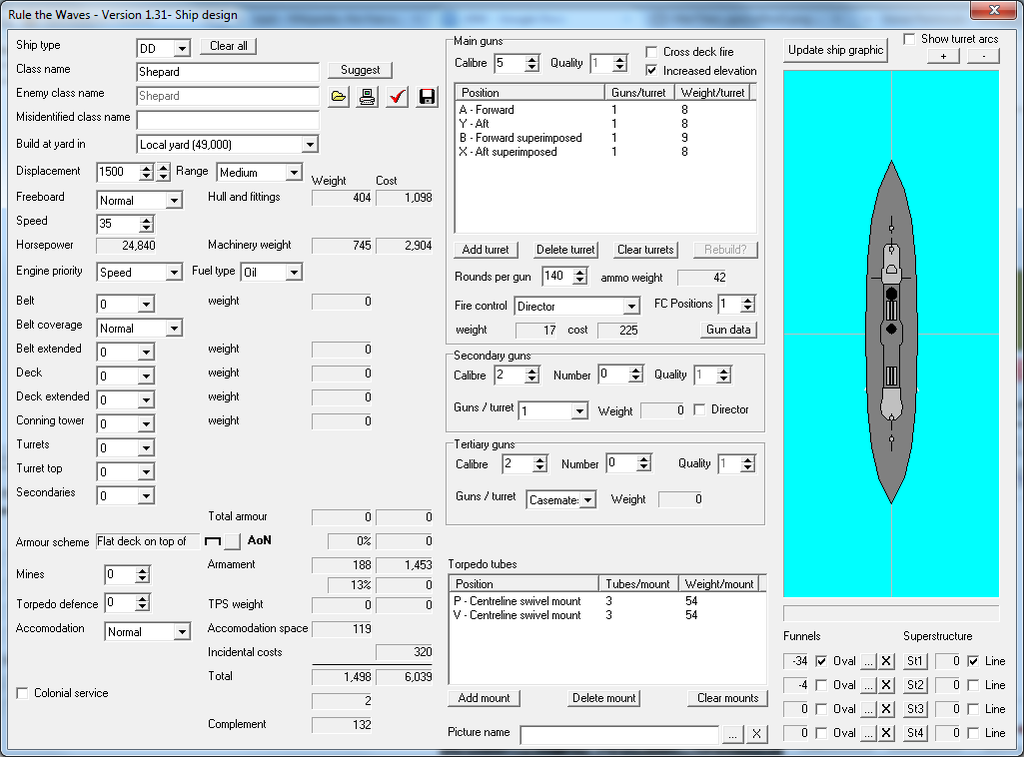

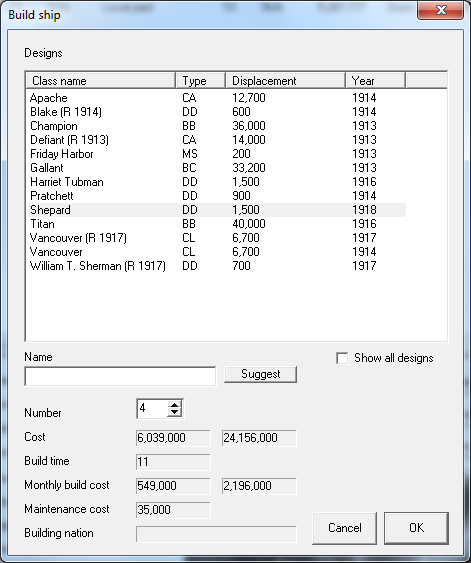

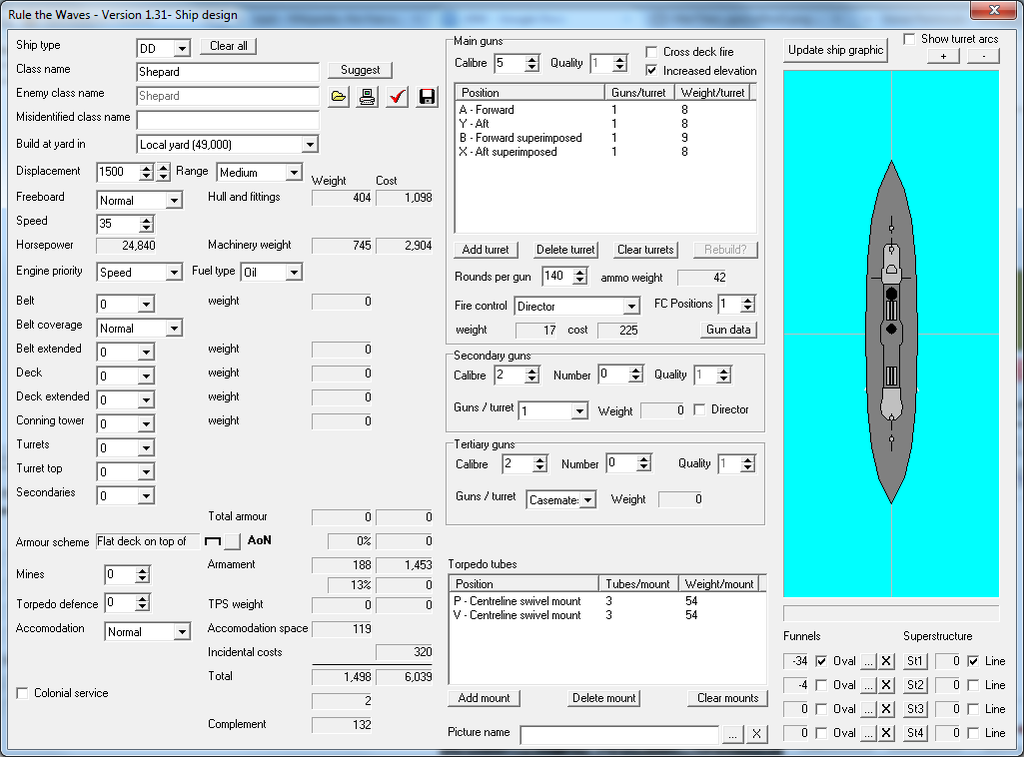

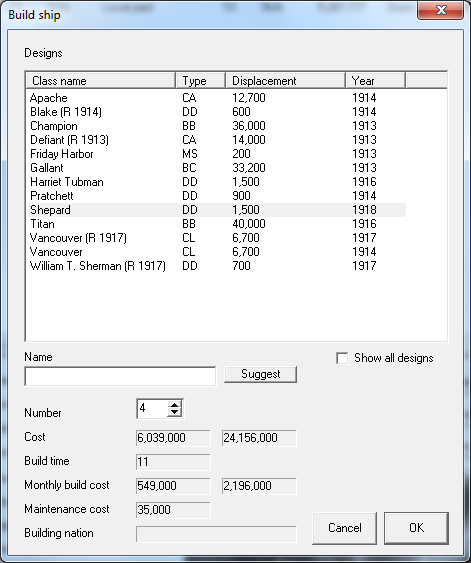

The Navy ordered new 1500t destroyers. The new

Shepard-class destroyer was made to be a fast gunship destroyer instead of relying upon torpedo armament, with four centerline 5" guns and only two triple torpedo mounts. Her design speed of 35 knots was above anything yet attempted in raw speed.

The most important innovation was the director firing affixed to the destroyers, giving them superior accuracy. Four ships were ordered:

Shepard,

Crusher,

Hawke, and

Anderson.

The new

Tubman-class destroyers were ordered to join the blockade forces at Scapa Flow.

A new Austro-German offensive continued the steady falling-back of Russo-Hungarian forces. The violence of Kun's

coup had been a jolt to non-Communists in the Hungarian rebellion and confidence in the Soviets plunged to lows, with more defections to the Austrians proceeding from reports of further Communist atrocities.

In truth Kun was retreating from his aggressive posture of the prior month, culminating with inviting the Diet back into session at the end of the month. He felt compelled to by the remonstrations of Stalin and the clear hostility of Lenin, who declared he would consider Kun a renegade if he did not get his forces back in line. This was Kun's acquiescence to the demarche.

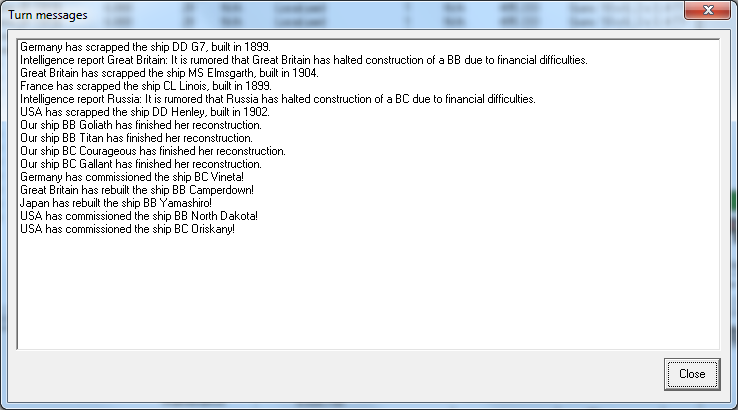

August 1918

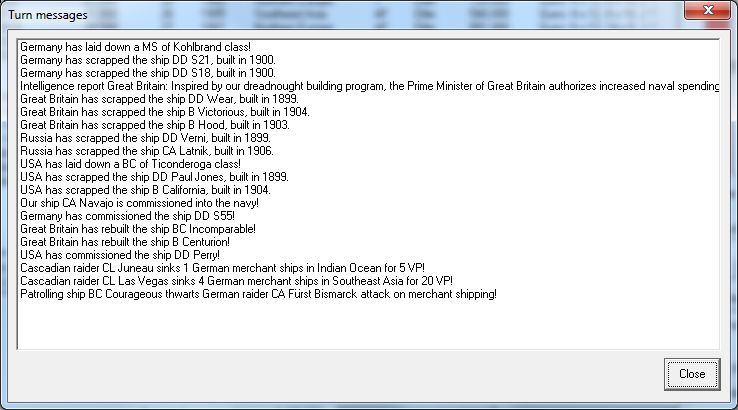

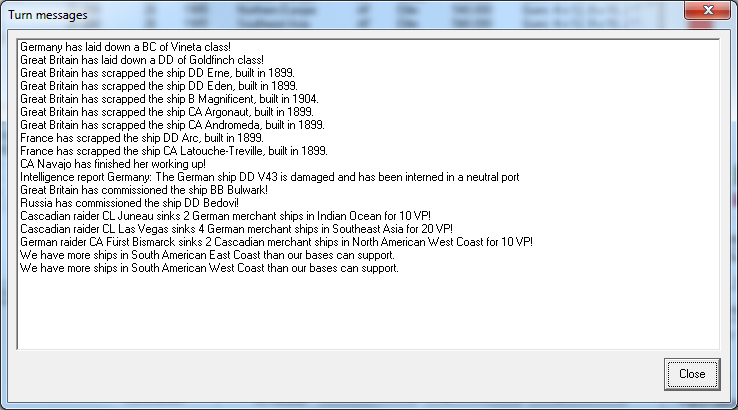

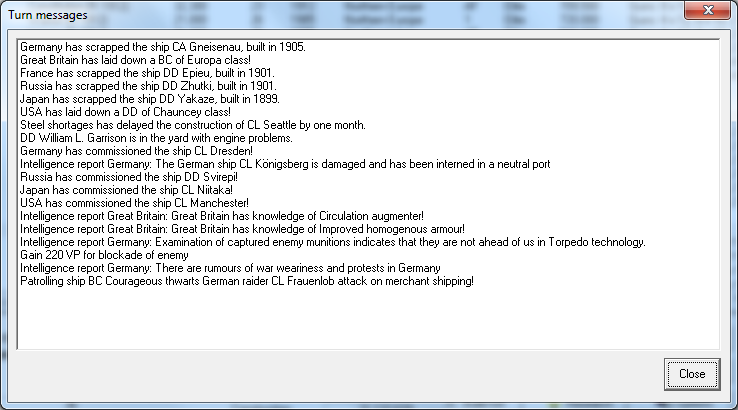

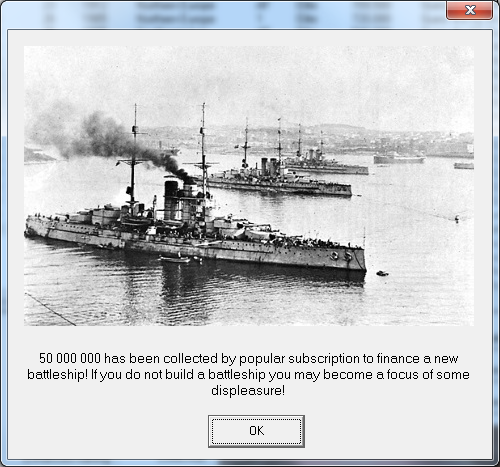

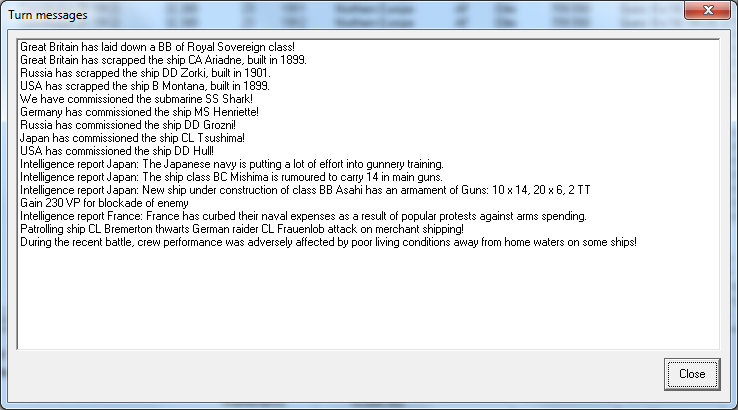

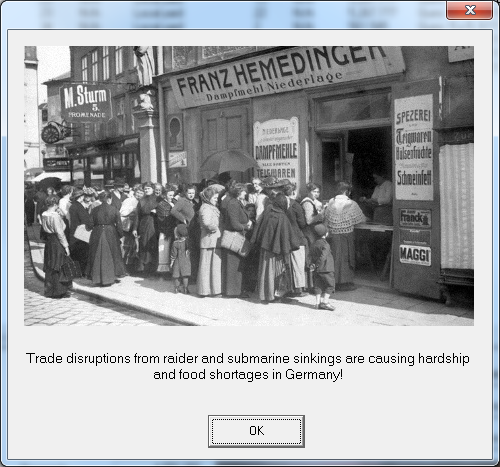

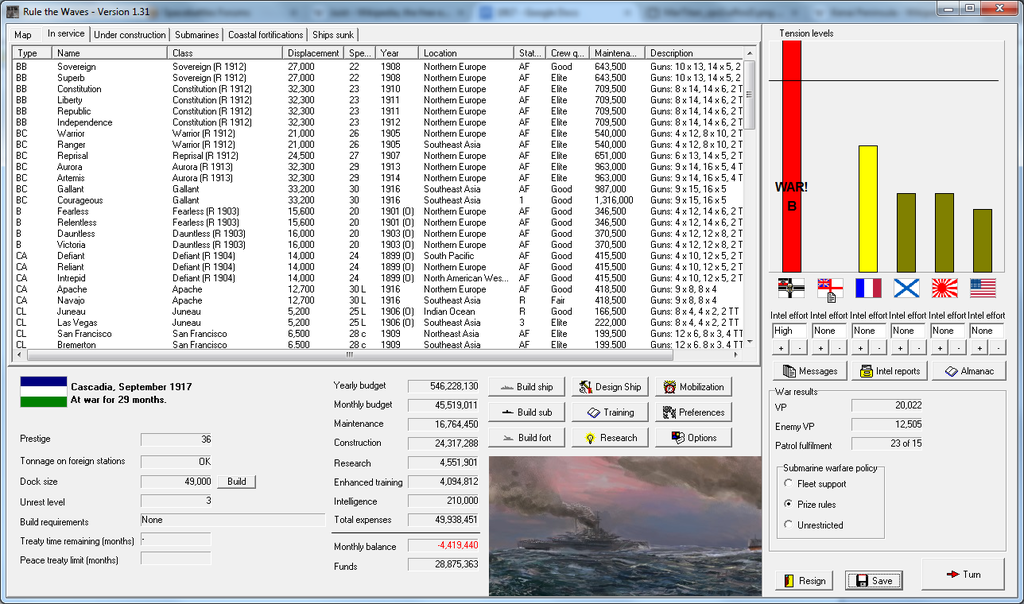

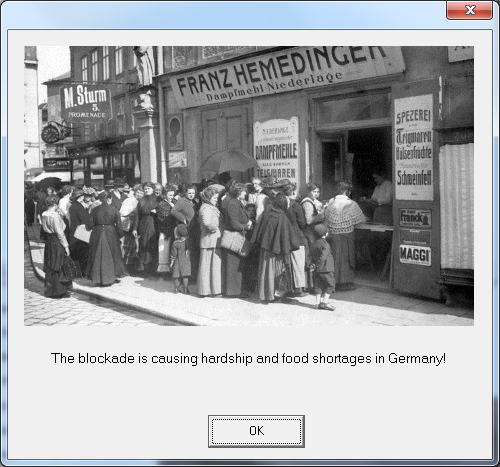

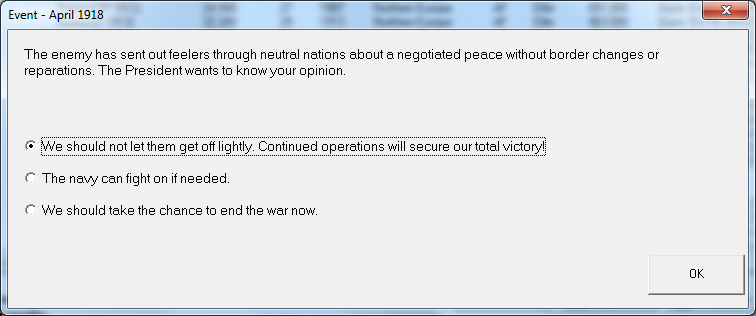

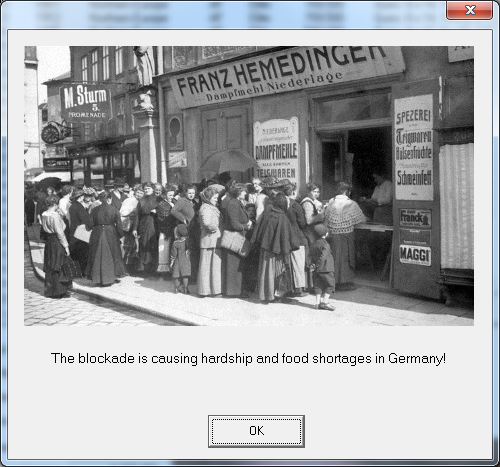

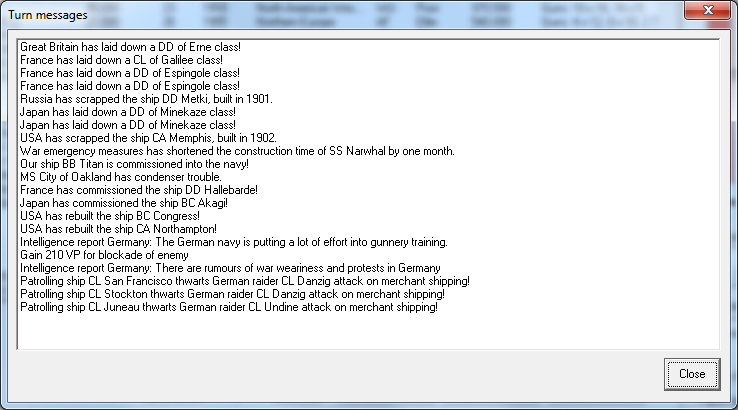

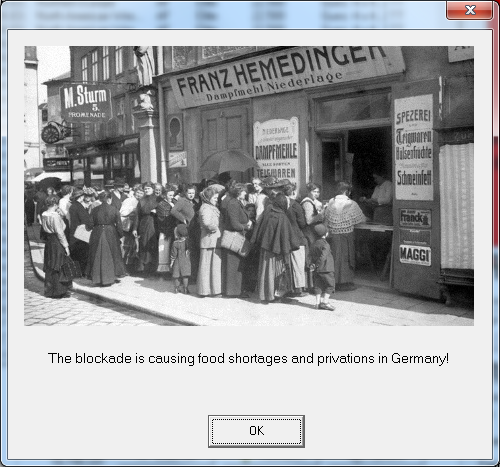

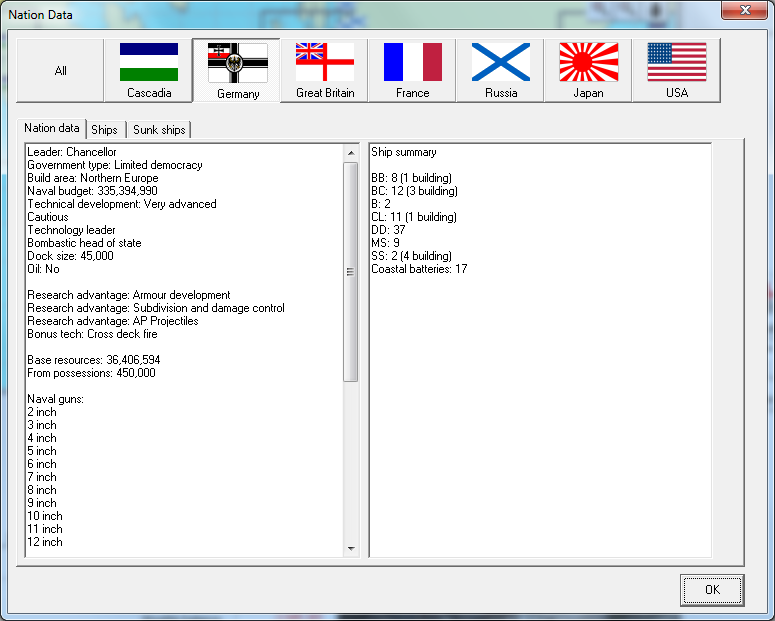

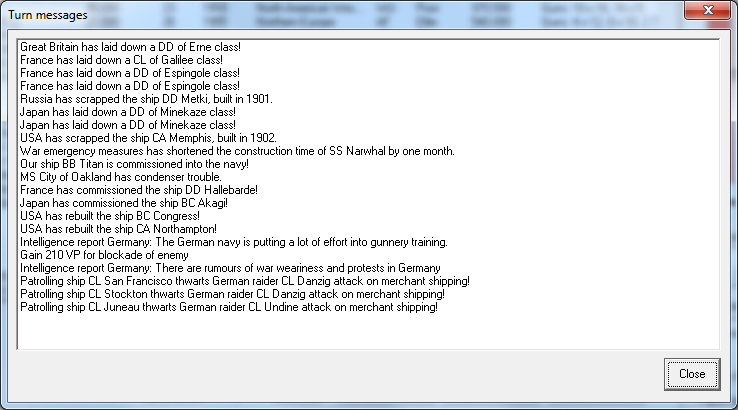

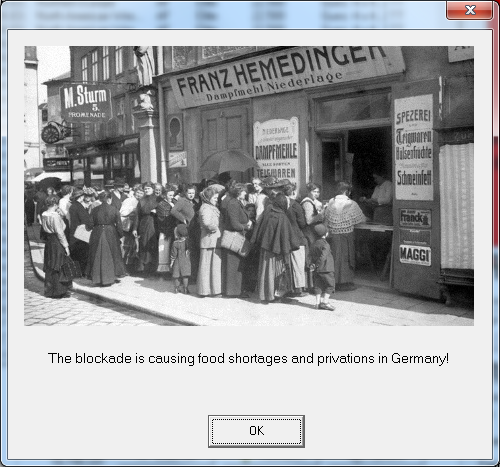

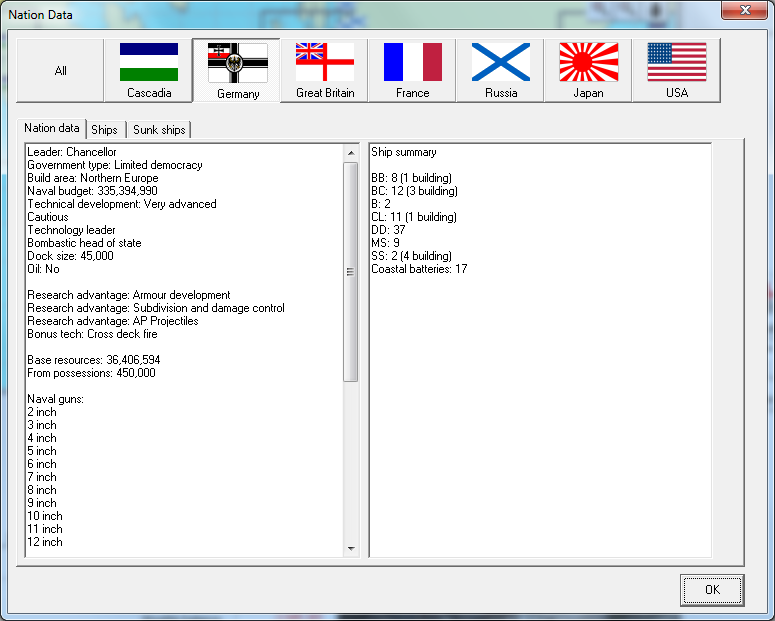

German newspapers reported a new round of ration reductions that sparked even hotter public protests. The Reichstag was now unanimous in demanding peace with the Allies, as the Communist threat from Soviet Russia was considered more important by Conservatives, that the fate of a colony was not worth failing to save the Fatherland from Communism. A deputation of leaders from both houses and all parties descended upon the Kaiser, as well as his generals, to insist on immediate peace talks with Britain and Cascadia.

For the first time, even Ludendorff demurred on the possibility. But the prospect of reclaiming all of Hungary from the Hungarian collapse made him reluctant to agree to the growing list of allied demands.

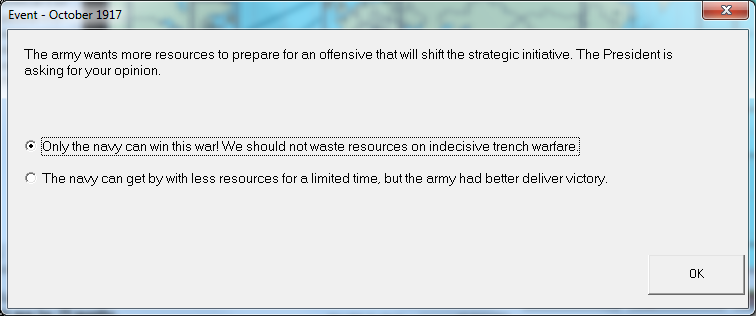

Meanwhile, after three years the actual front that sparked the war was still raging. British, Portuguese, and now Cascadian troops had driven the German colonial forces back into Tanganyika, at least on the map. In truth the irrepressible Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck continued to harass and infuriate Allied commanders with daring attacks and maneuvers that kept the allied armies from overwhelming his forces. Cascadian General Peter Lundsen proposed that Lettow-Vorbeck be compelled to stand and fight by allied seizure of Tanganyika's richest areas. But while London was willing to send more regiments to the effort, President Lakeland was enjoying the relative tranquility of the homefront compared to the prior war and was not keen on sending thousands of Cascadian troops to occupy African soil that would either be returned to Germany or claimed by Britain.

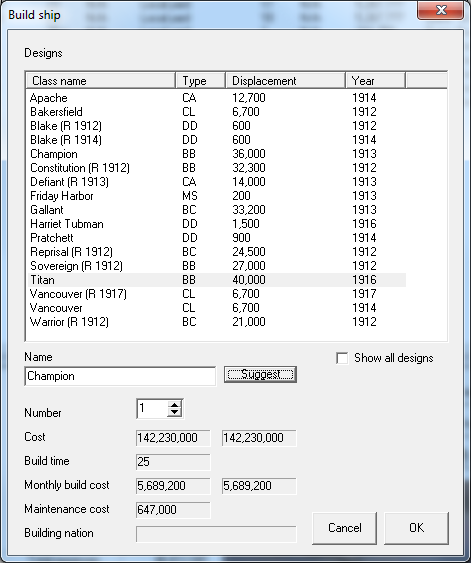

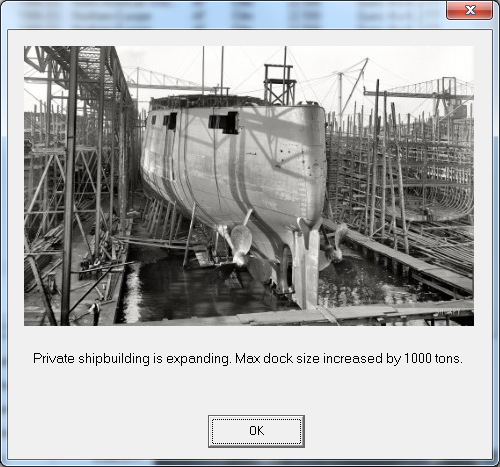

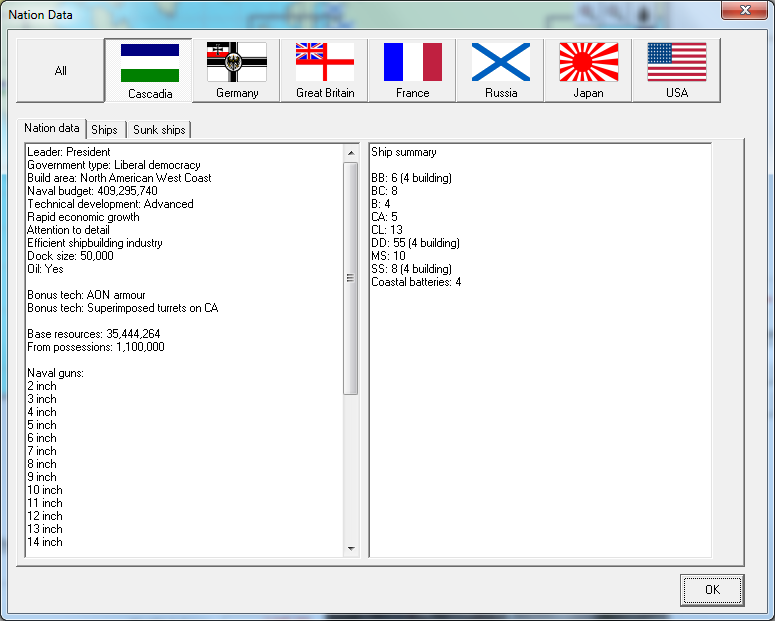

The war's expanded naval orders, and new orders for capital ships from Chile, prompted an expansion of the docks at Moran Brothers in Seattle.

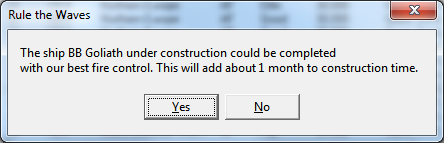

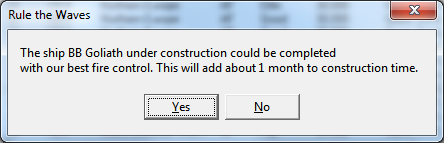

The Admiralty decided to prolong the construction of the

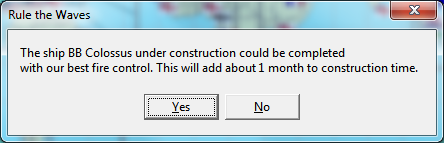

Goliath to install the new improved director firing system into the new "super-sovereign" battleship.

The British Admiralty requested permission to purchase schematics for Cascadia's new reduction gears. The offer was accepted.

Ship designers further improved their method of calculating the weights involved in ship design, improving the efficiency of future designs' use of weight.

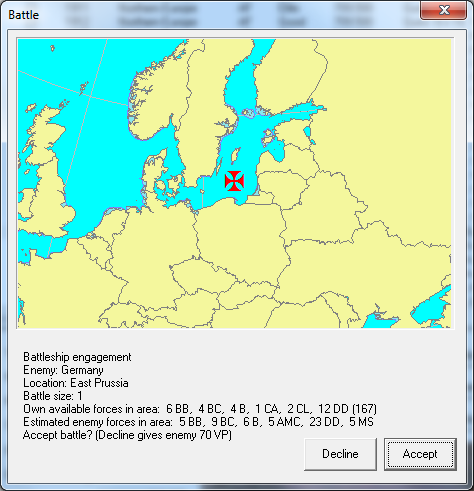

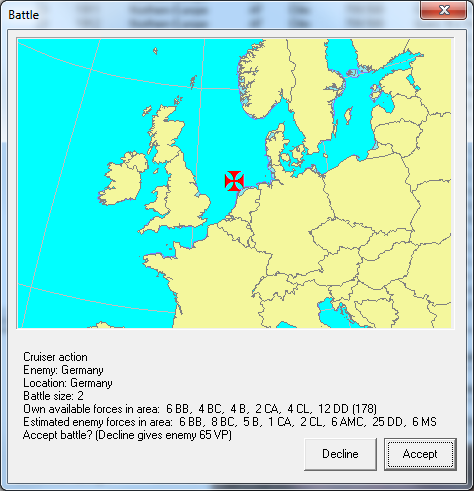

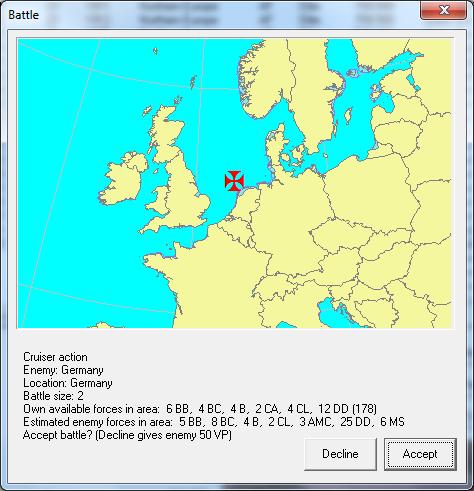

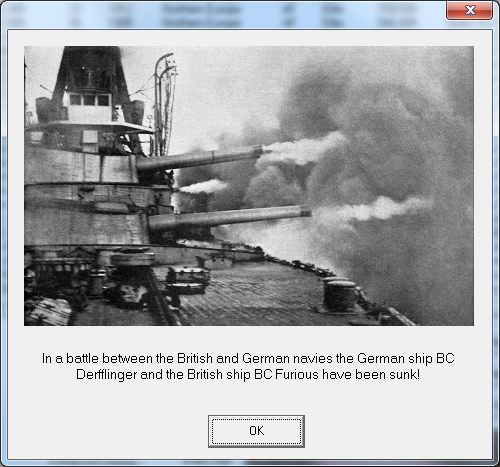

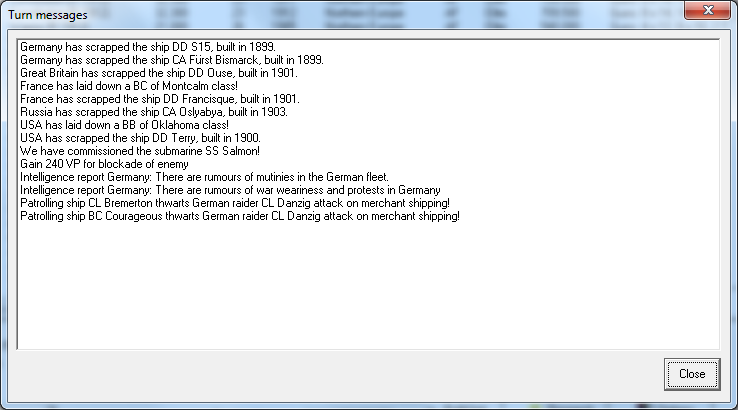

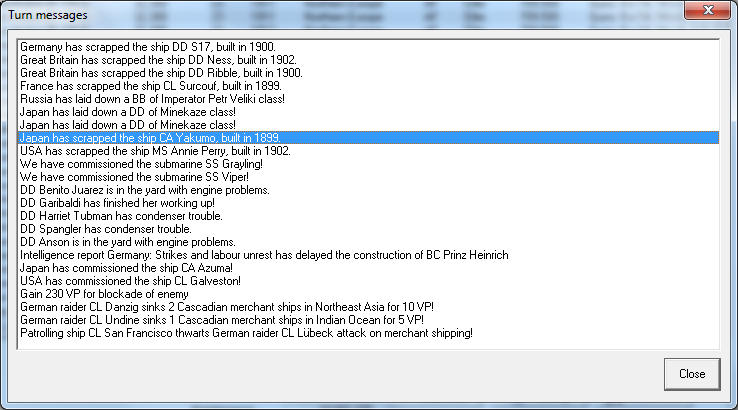

Germany's economy was becoming increasingly crippled by the blockade as the month went on, increasing the pressure on the German admiralty to Do Something about it. Pressed on the issue, Admiral Scheer proposed an all-or-nothing sortie against the British coast, with the goal of bringing the allied fleets to battle and defeating them piecemeal, or being destroyed in the attempt.

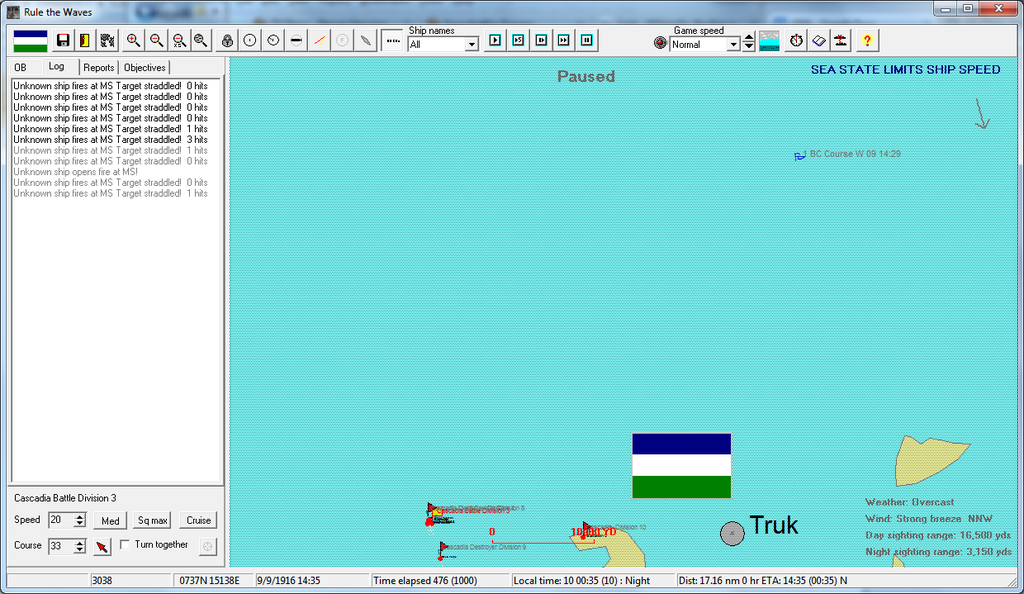

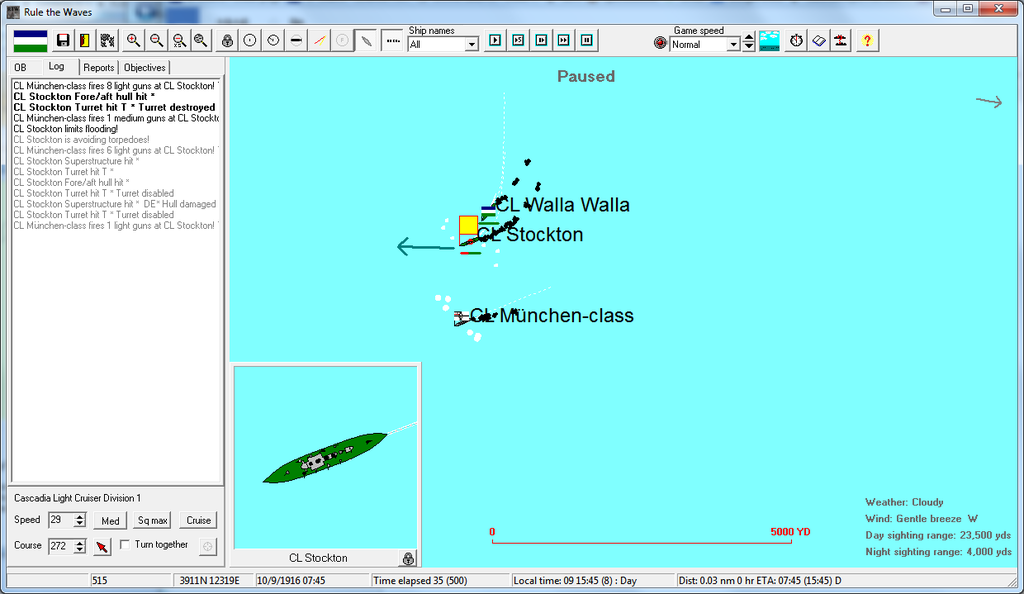

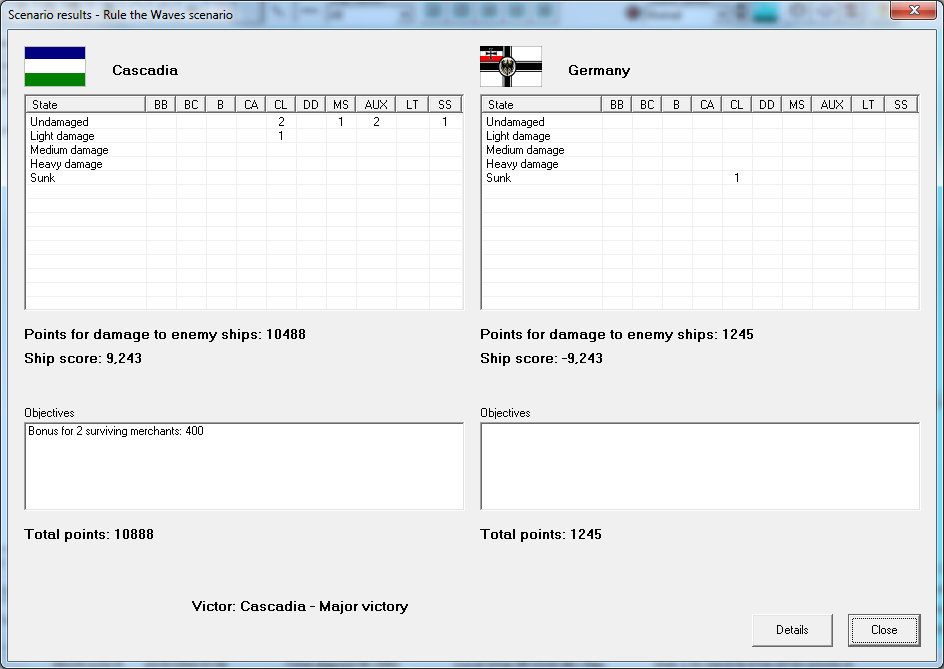

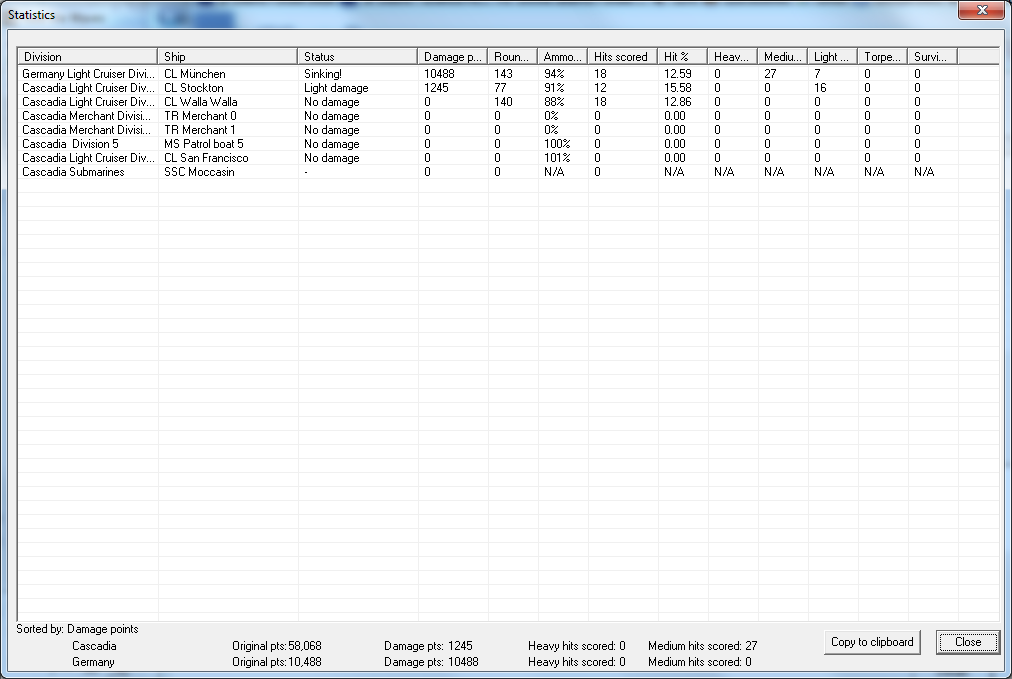

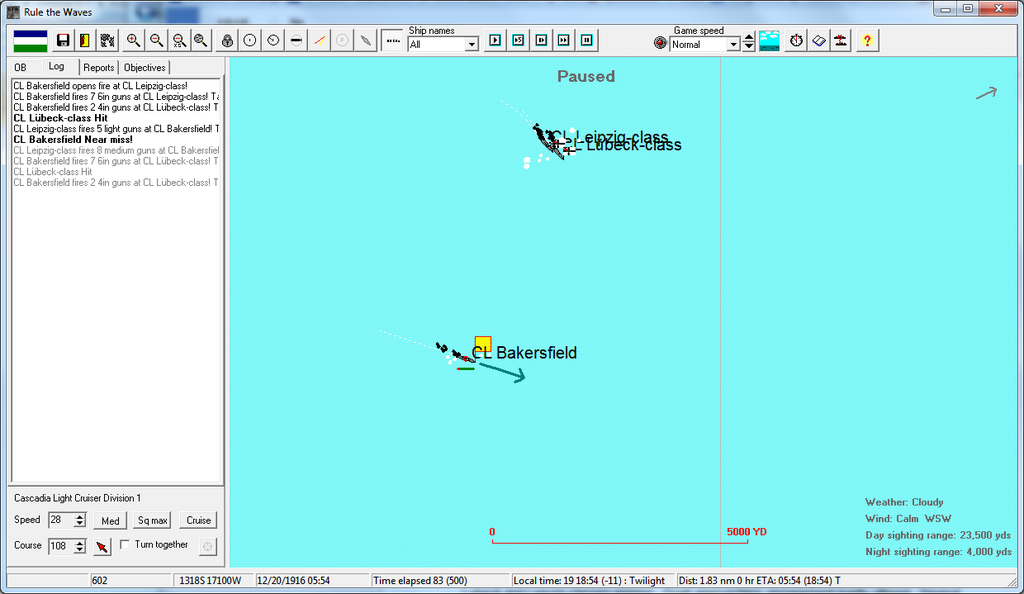

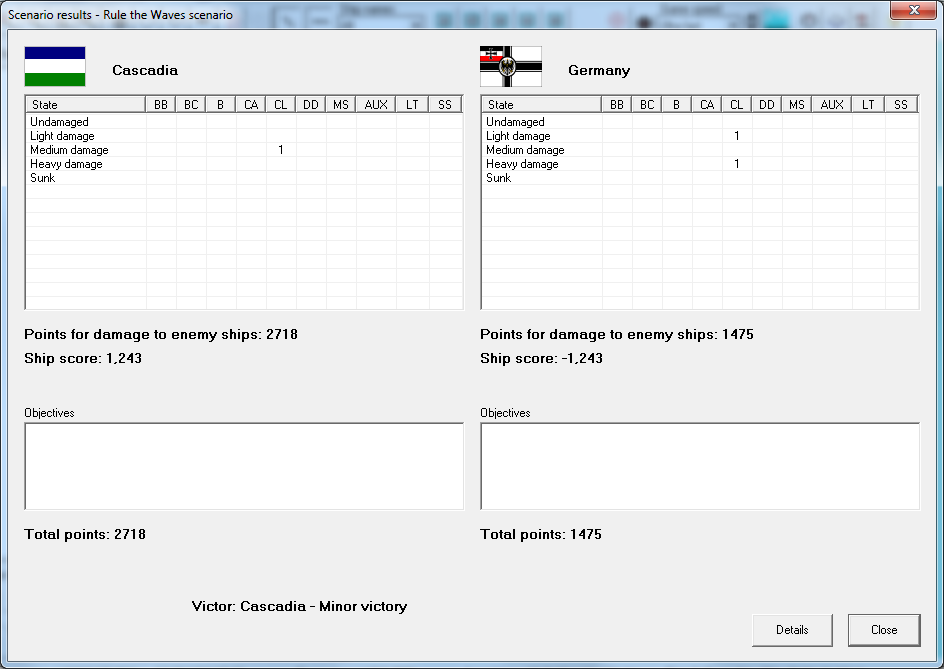

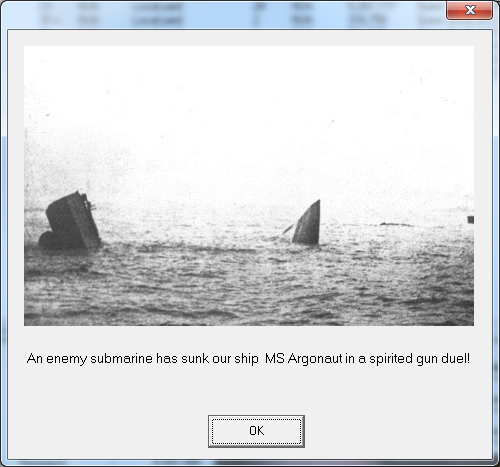

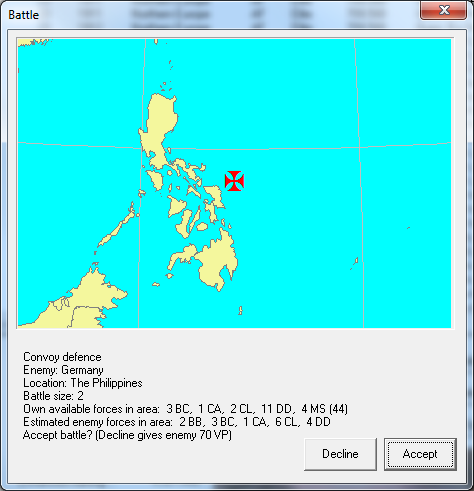

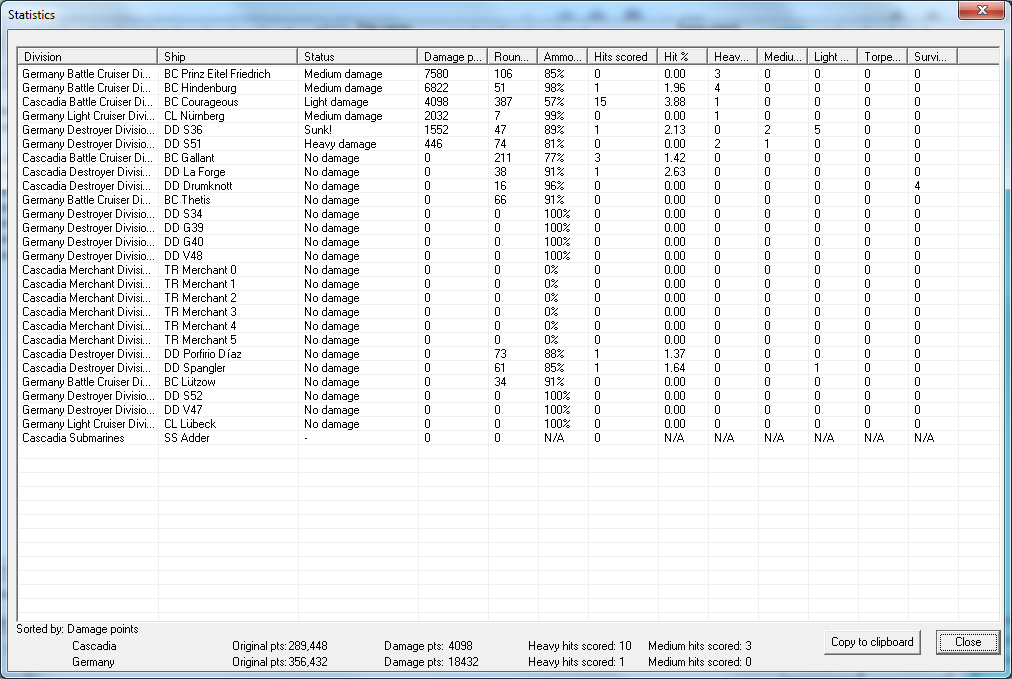

Cascadian submersibles had a dismal month, sinking only one German ship. The British managed a few more sinkings as well.

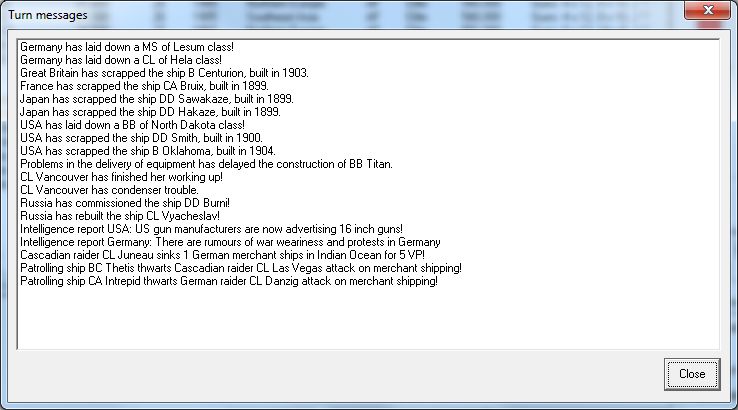

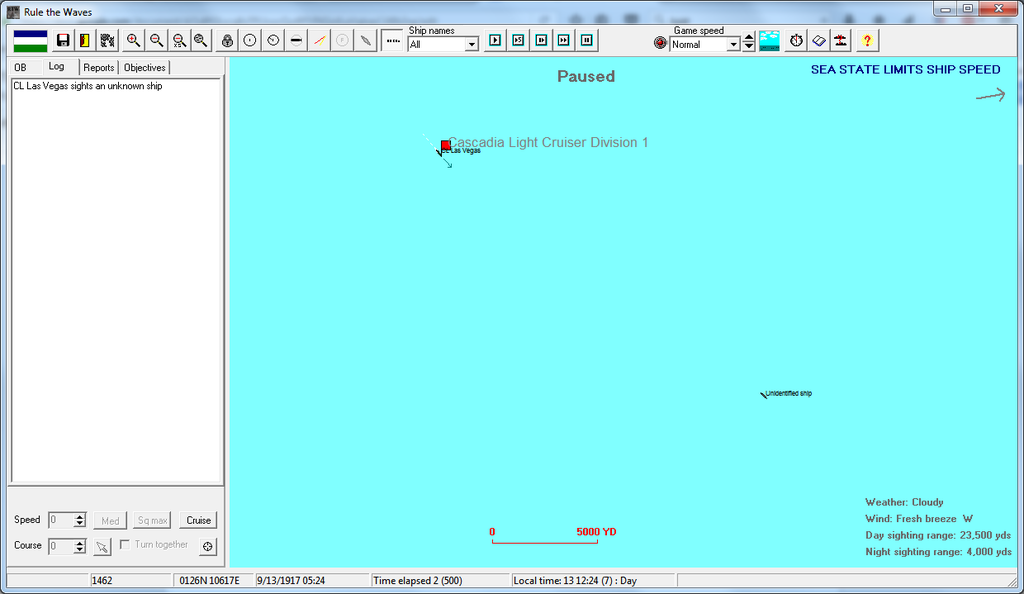

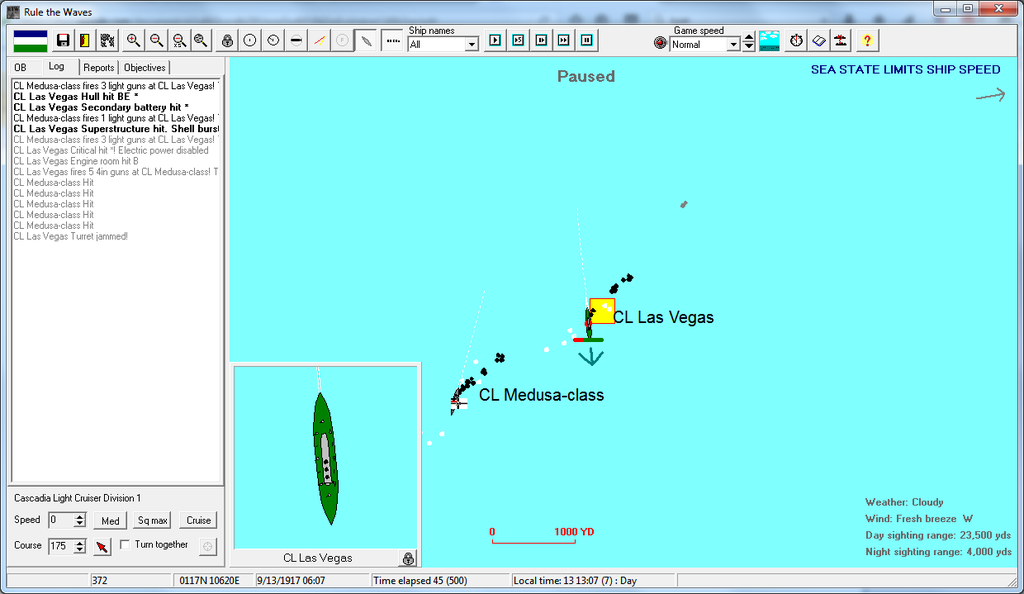

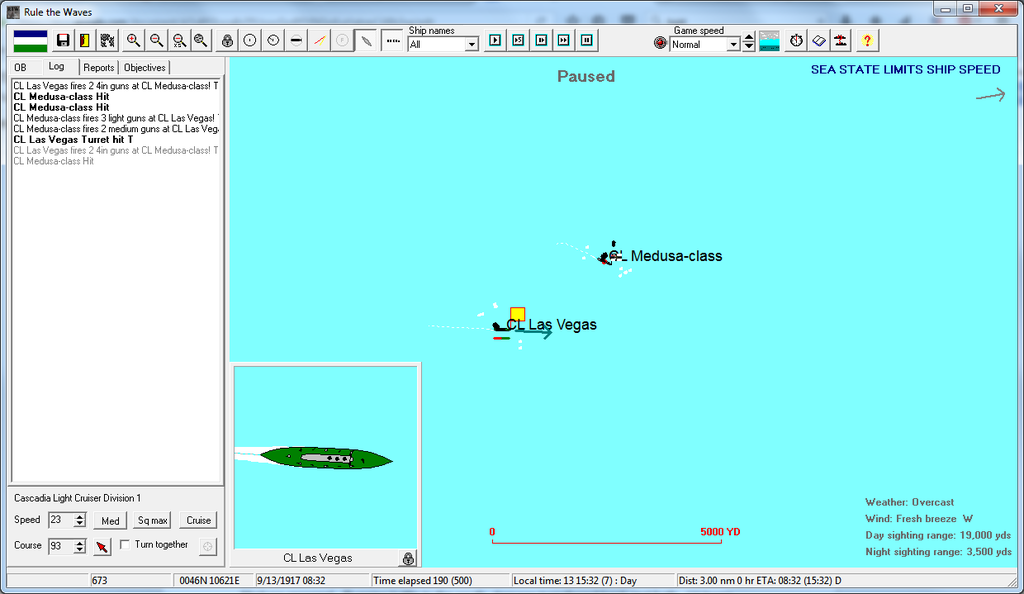

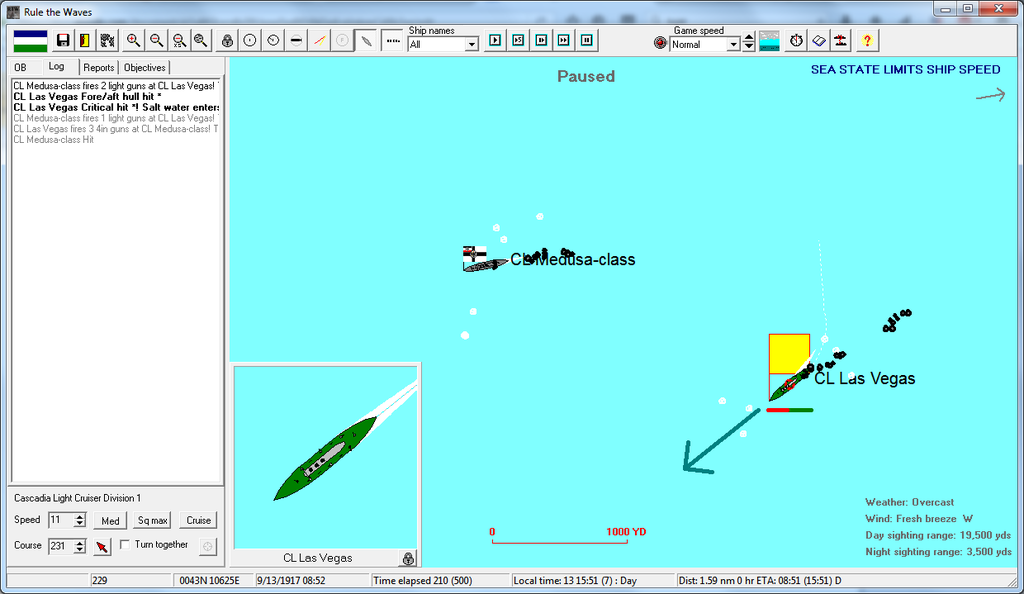

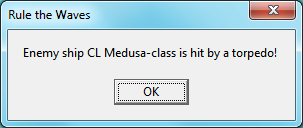

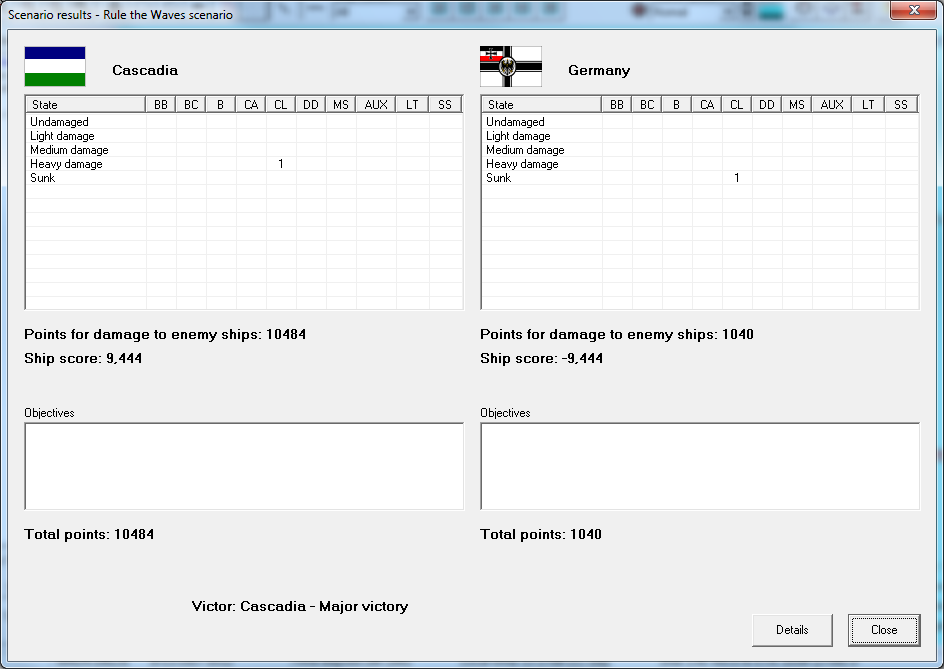

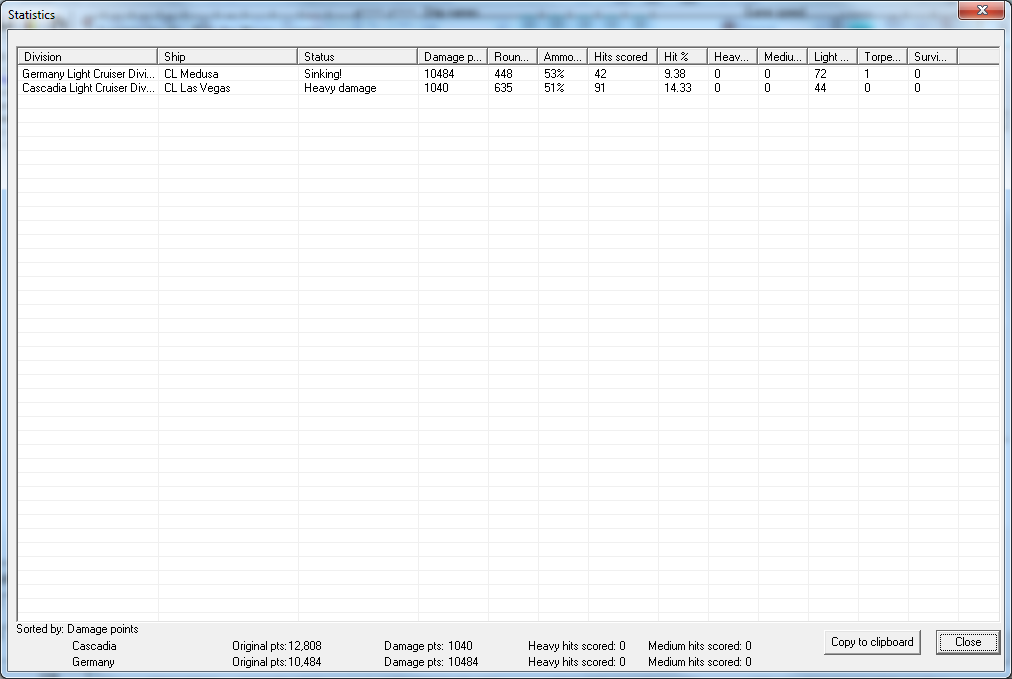

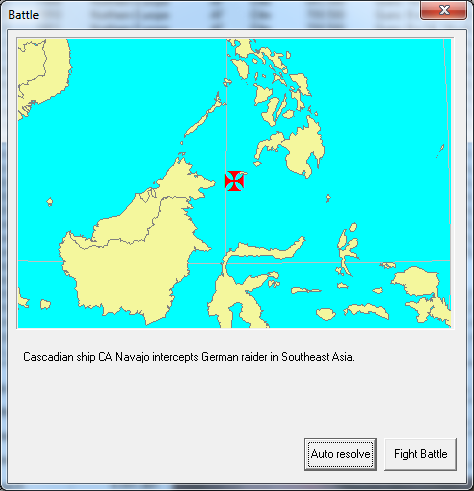

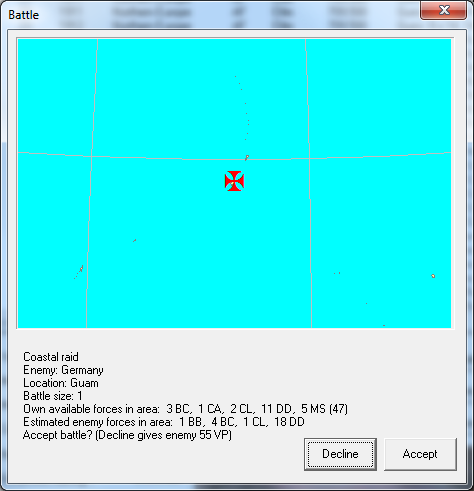

The career of the raider

Danzig came to an end off the Philippine Islands, where the

Las Vegas ran her down and sank her.

The

Titan was sent back to the yards to be refitted with the improved firing director system.

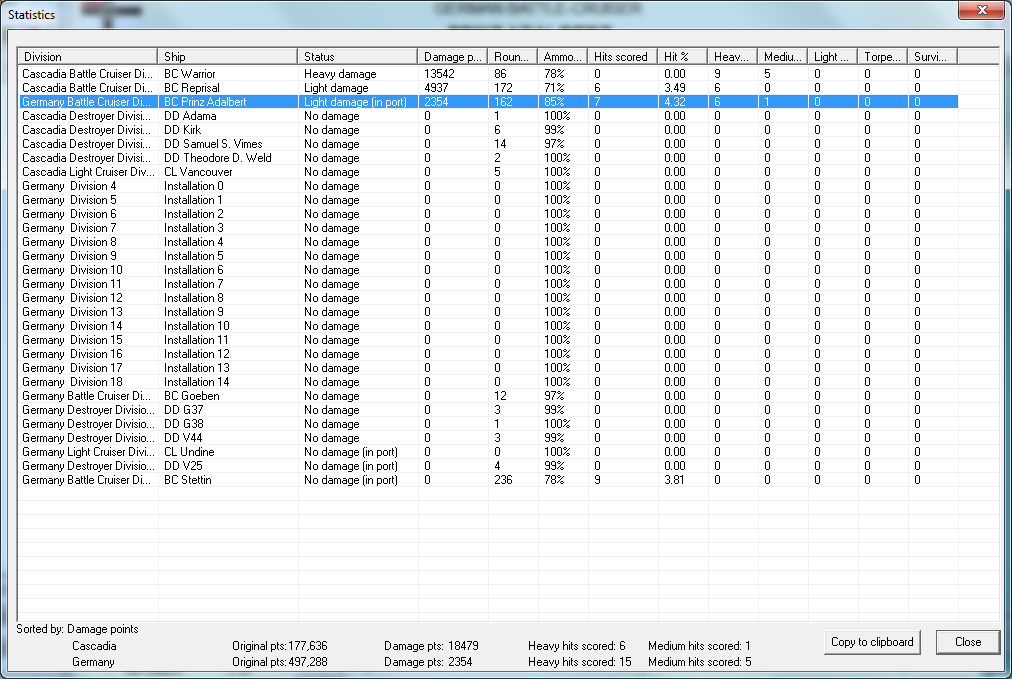

On the final day of the month, Scheer's desperate "death ride" was set to begin. But as the order came for the

Hochseeflotte to depart Kiel, the ships did not move; the sailors of the fleet refused to put to sea. When force seemed imminent the sailors seized control of the armories of their ships and naval base and swept over their opposition, declaring their intent to march on Berlin and demand immediate peace.

September 1918

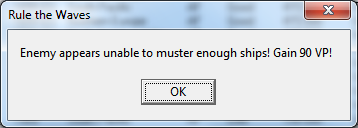

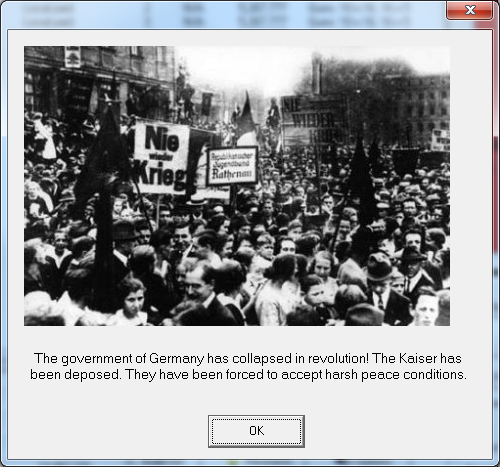

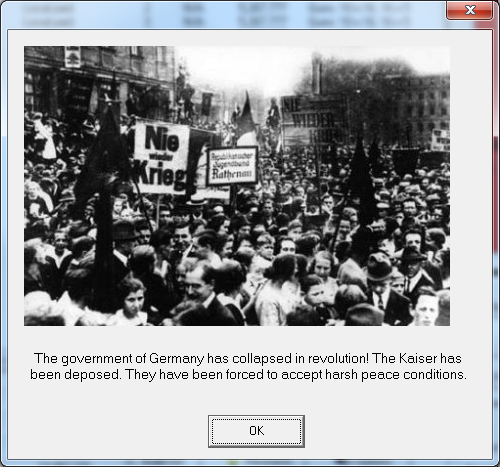

News of the Kiel Revolt ran across Germany. It proved to be the flame that set off a full-scale revolution; the starving workers and even middle-class Germans took to the streets to demand an immediate end to the war, both with Britain and Cascadia and with Russia over Hungary. The

Reichstag, surrounded by protestors, reflected the will of their enraged people by declaring an end to all military appropriations until the Kaiser agreed to an immediate armistice.

This was not far enough for some radicals, who blamed the war on the Emperor. The SDP and its allies, fueled by the enraged mobs across the country, pushed through a resolution in the

Bundesrat calling on the Kaiser to abdicate in favor of his son, and to re-write the national constitution to make the Chancellor responsible to the legislature.

The German Army was horrified by the result of such a demand. German troops were called in and the decision was to seize the legislature and imprison the SDP members and others calling for the deposition of the Emperor. This, however, sealed not only the Kaiser's fate, but the fate of the entire monarchical system of Germany. The Army troops joined the protestors and the

Reichstag and declared themselves in favor of the popular uprising.

At this point, with his beloved soldiers threatening to storm his palace to force him to leave, Kaiser Wilhelm II lost all hope. He immediately abdicated and boarded a train for Vienna with his family. News of his abdication rippled across Germany and prompted local disturbances to demand the same of the other monarchs of the country, with the

Reichstag voting on elections to form a new republican constitution. Within ten days of the start of the month, the entire political system in Germany had been completely altered.

The new German state also faced the need to end the war, and to end it before the people turned against them as well. Fierce debate raged during these first ten days over the subject over how much to surrender.

Three things jolted the German leaders out of their impasse: the raising of the red banner, and Soviet flag, by the Kiel mutineers; the growing mobilization of French divisions in Lorraine and the Vosges, indicating an imminent invasion of Alsace; and the German Army on the brink of infighting and revolt. Faced with these threats, and the prospect of the Red Army and the French Army marching into German home soil, the new Republic decided to submit to the demands of the British and Cascadians and hope that the end of the blockade would restore public confidence and give Germany an edge against the Soviets.

On the 11th of September, 1918, the German Republic wired to the Ambassador in Paris to instruct him that they were seeking "any peace term" to end the blockade and the war.

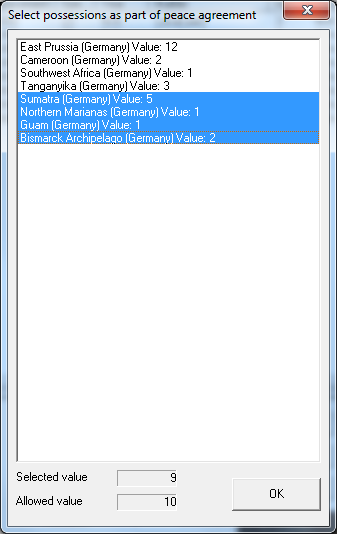

The ambassadors in Paris had been briefed on what their governments expected. The British expected an immediate German withdrawal from Mozambique, major economic concessions, and reparations. As always, the Cascadian demand was for the Germans to turn over their Pacific holdings to Cascadia. The German delegation in Paris wired back to Berlin the terms, and a warning that Georges Clemenceau was already arguing for France to join the war if it continued to seize Alsace.

Another night of fierce debating gave way to tired, exhausted acquiescence. On the 13th of September, Germany officially declared it would accept the terms as a condition for an armistice if it received an immediate armistice and a lifting of the blockade.

By now the news had spread to the public. Rapturous celebrations gripped London and Portland. President Lakeland won a $20 million Cascadian fund from Parliament to fund the implementation of any territorial exchange. The German terms were accepted and the armistice was officially signed in Paris on the morning of the 15th, ending the Anglo-German War.

The negotiations for the peace would take place in neutral France. The French, while neutral, made clear their own emotional stake in Germany's humiliation by establishing the peace negotiations in the Hall of Mirrors are Versailles. The negotiations lasted through much of the remaining year. In the end, the Treaty of Versallies signaled the official end of the war, although practically it only codified the terms of the German armistice.

There was still fighting in the east, though, that would last into the next year. Germany's military commanders, and its conservative politicians, held out hope that they could at least defeat the Soviets and take more of Poland. But it remained to be seen if the populace would accept a continuation of the land war, even with the blockade lifted and grain from North America pouring into Hamburg, Bremen, and the other old Hanseatic ports along the North Sea. Anti-war protests, spurred by Rosa Luxemburg and other Socialist leaders who were pro-Soviet, continued to rock Germany through the year.

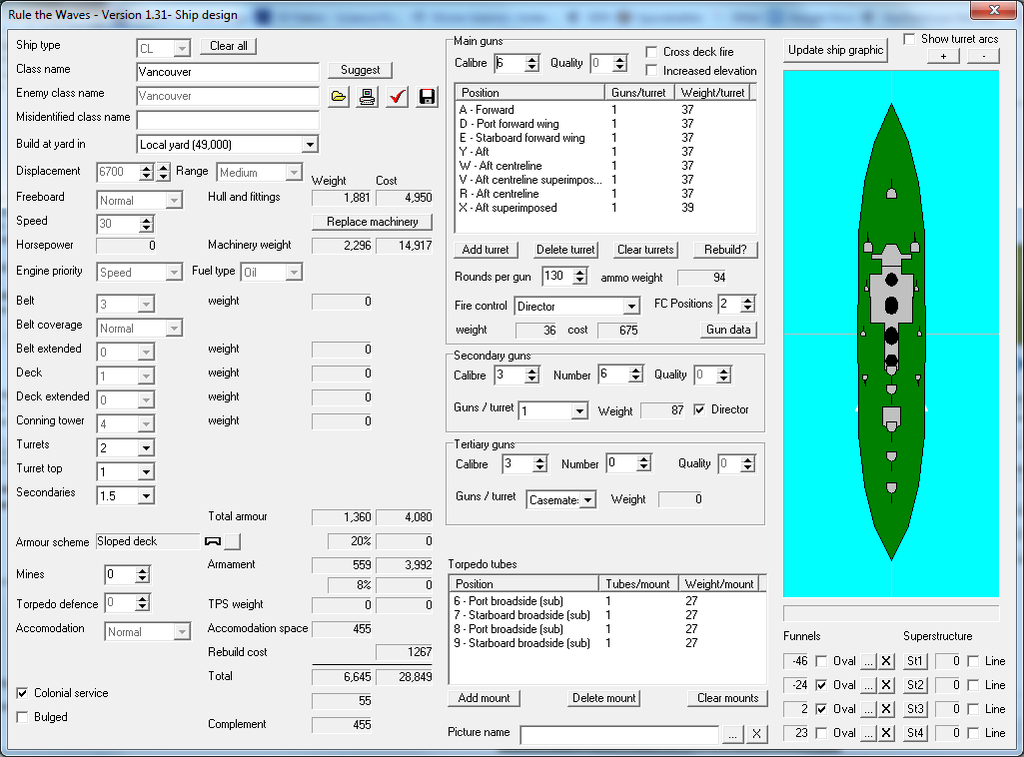

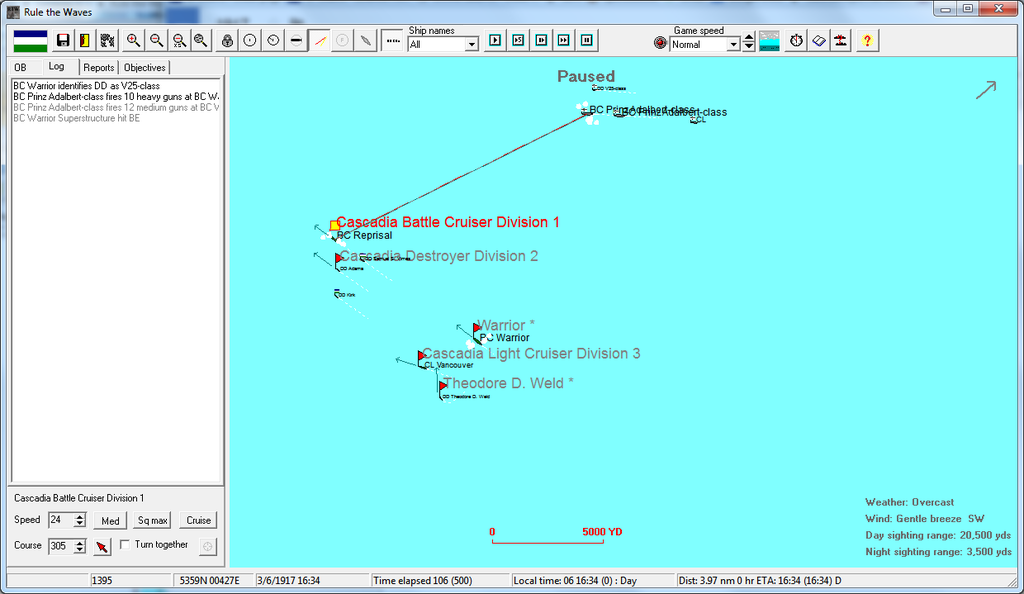

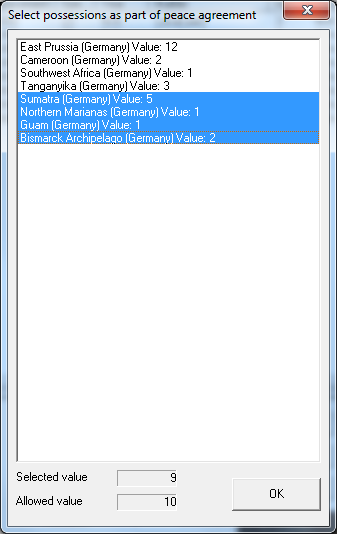

As for the peace treaty with Cascadia and Britain, as part of the series of reparations over the war, Germany turned over its newest

Prinz Adalbert-class ship, the

Freya, to the Cascadian Navy.

And she signed over her Pacific Colonies, as required by Lakeland. The Marianas, the Bismarcks, and Sumatra were turned over to the Cascadian Republic, while German New Guinea was transferred to British New Guinea. It was, for the Germans, arguably the most bitter term of the peace treaty, even when considering the relative cost of the actual holdings. Their Pacific holdings had been part of the German push for

weltmacht. Now the German Empire had been driven from the Pacific, surviving only in Africa.

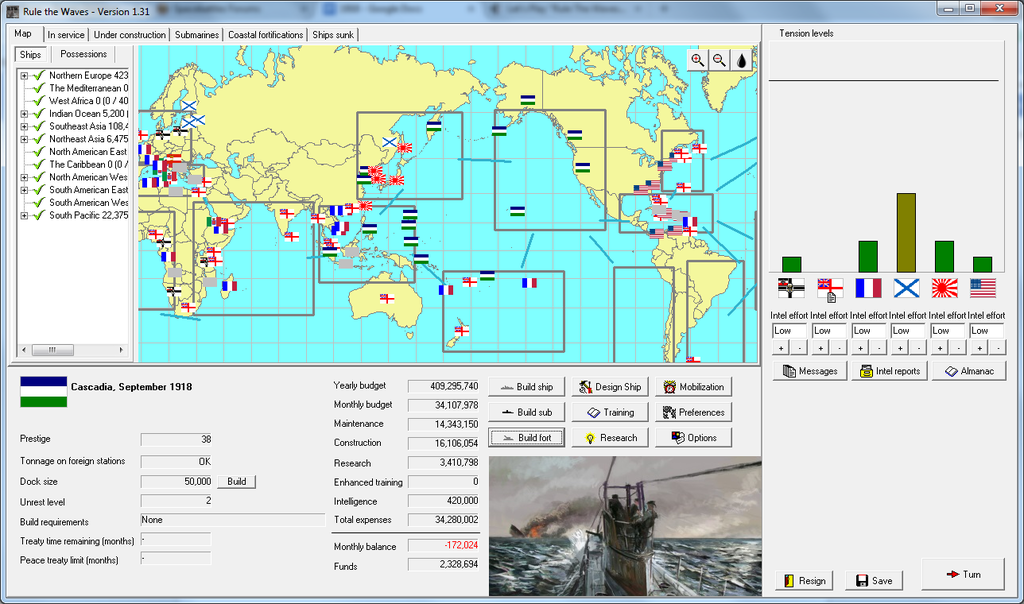

For Cascadia, however, it was the clinching of her rising star. The Cascadian Republic was now the most powerful nation in the Pacific.

"And such was the culmination of twenty long years of struggle and strife. The price of Cascadia's rise to Pacific hegemon was four wars, many thousands of Cascadian men fallen in the fields of Lorraine, and millions of dollars out of the growing republic's treasury to field the battle fleet that, in the end, made the victory possible.

But with the price paid, the glories won, and the Evergreen Tricolor now flying over the battlements of Guam and Saipan, the jungles of New Britain, and the tropical riches of Sumatra, one in that time had to wonder what might come next. And, perhaps most importantly, how the other powers of the Pacific might ultimately react to the new heights of unprecedented power in the hands of the Cascadian nation." - Excerpt from "Empire of the Pacific" by Dr. Anthony Welsing, Cascadian National University (published 1953)

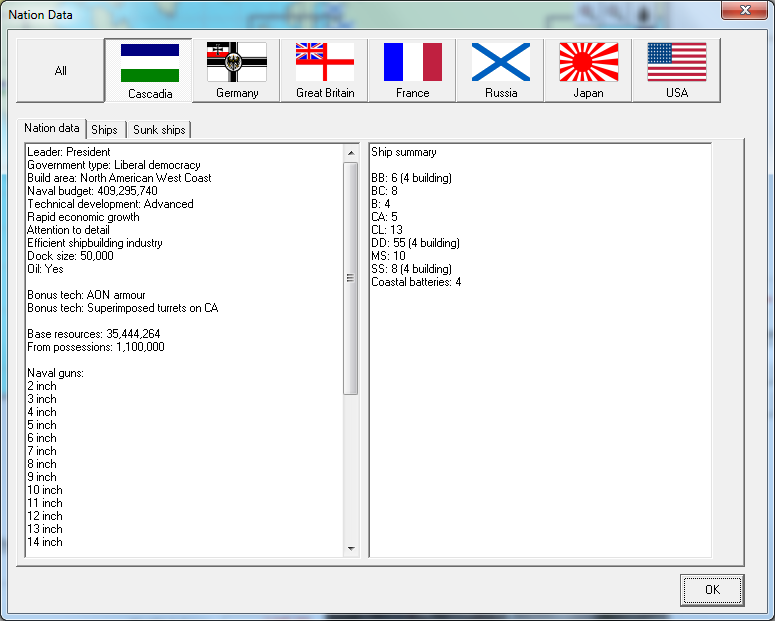

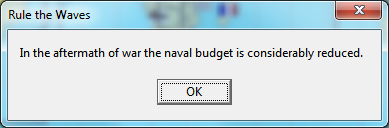

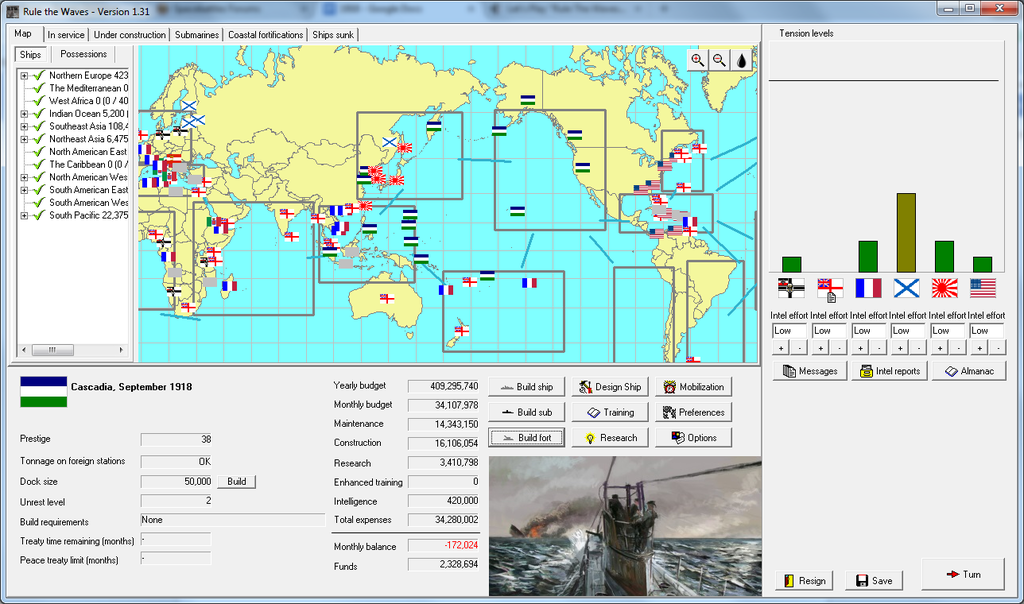

With the end of the war, Parliament immediately cut funding for the military, re-distributing money to relief for merchant lines that lost vessels in the war and to the costs of taking control of Cascadia's new Pacific Empire.

The end of the war prompted vast national celebrations. Unrest fueled by ongoing anti-war sentiments and activities was curtailed.

Unrest down to 2

Although Lakeland had been adamant on territorial concessions in the Pacific, he proved generous with the newly-formed German Republic. His anti-Socialist sentiments made him supportive of the Republic's ongoing war with the Soviets. Lakeland took the step of ordering additional troops sent to Petropavlosk-Kamchatskiy and promoted war loans to Germany for fighting "the Reds" in several circulars to the Conservative, Liberal, and Populist Parties. Cascadian ships were even offered to help get the German troops departing the Pacific colonies back to Europe for the fight against Communism. Several political leaders formed the German-Cascadian Food Relief Society to help buy wheat and other food desperately needed to alleviate the starving German population.

While German bitterness would not be alleviated by this alone, recognition of Cascadian support against the Soviets did improve relations in the immediate years post-war.

Relations with the rest of the world, save the Soviets, were splendid, but there were signs of potential trouble. The colonial lobby in Paris saw Cascadia as a threat to their Pacific holdings. And Japan was increasingly discontent with the rise of Cascadian power in East Asia. Time would shortly tell how these states would react to the rise of Cascadia.

Tensions with Germany to 1, UK 0, France 2, Russia 5, Japan 2, US 1

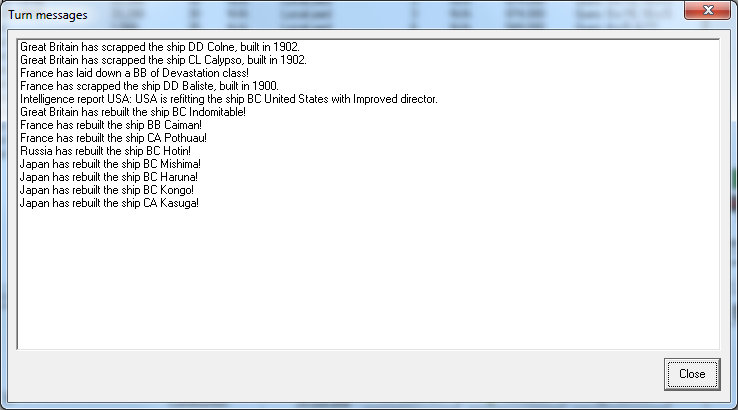

The

Colossus' construction schedule was prolonged to install improved firing directors.

Reilly & Colette reported that they had completed successful testing of an improved 16"/50 caliber gun model.

The costly enhanced training regimen for the Cascadian Navy was canceled to save up budget space under the new trimmed peacetime budget.

Naval Intelligence's budget for operations in Germany was slashed.

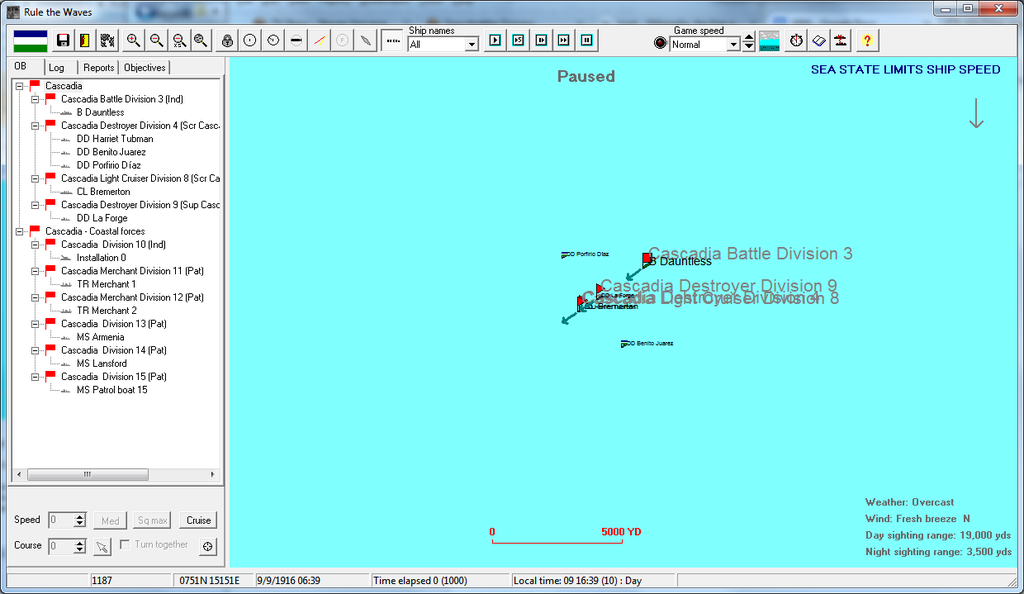

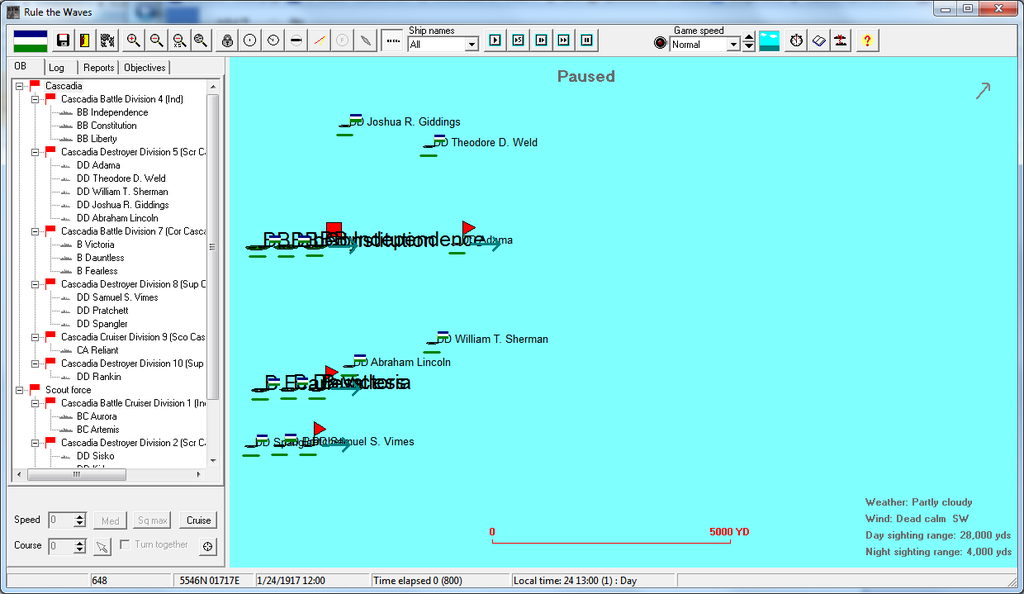

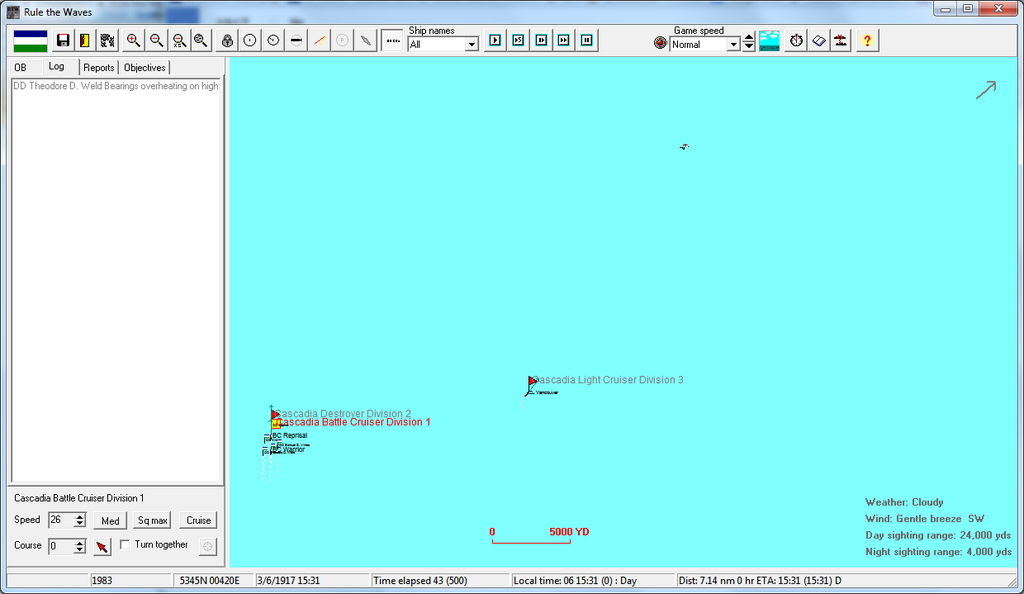

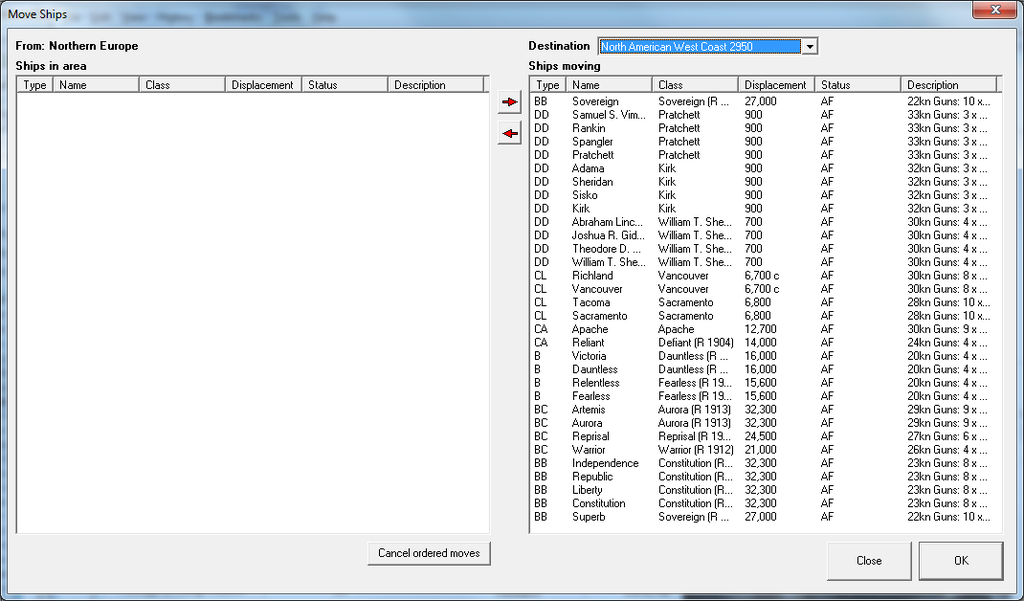

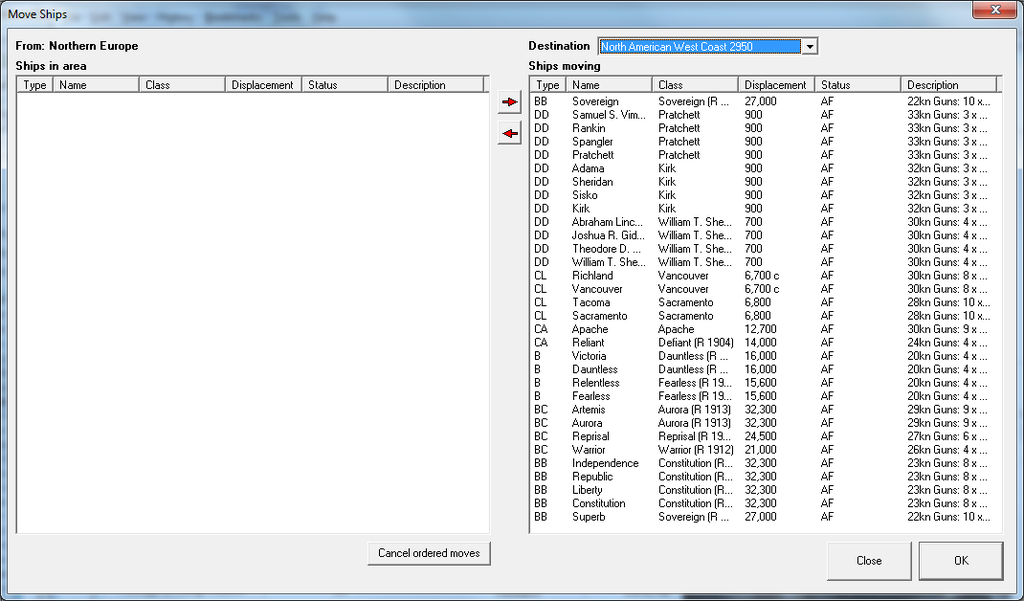

With the victory, the Cascadian Navy began redeploying. The Expeditionary Fleet was recalled from the waters of Scapa Flow on the 16th of September. On the day of their scheduled departure, the 29th, His Majesty's Government saw them off in a ceremony. "The British Empire will remember the Cascadian heroes who shed their blood in our common cause," stated First Lord Churchill. "May your journey home be made with fair skies and calm seas, with the gratitude of England ringing in your ears."

Churchill's remarks underlined the Liberal statesman's growing enthusiasm for the idea of a grant Anglo-American-Cascadian alliance, "the Covenant of the English-Speaking Peoples", that would police the world, deter further aggression by other powers, and resist the spread of Communism - Churchill would even argue for deferring German reparation payments so long as the German Republic remained at war with Soviet Russia. And while the sentiment was initially acceptable to many, it did not account for a growing discontent in London over the Cascadians. The British Left was incensed at Cascadia's territorial expansion on anti-imperialist grounds, and the British Right were just as appalled that the British were getting only a small territorial concession - German New Guinea and the Solomons - while the Cascadians had claimed the Bismarcks, the Marianas, and the gittering prize of Sumatra. Bonar Law outright attacked Lloyd George's acquiesence on the matter of the latter, pointing out that if any power should get control of Sumatra from Germany, it should be Britain, as Sumatra could be used to threaten British shipping through the Strait of Malacca and could, indeed, provide the means to sever Britain's shipping lanes to the Far East and Australia.

But the agreements had already been made: Cascadia had agreed to concede rights on Sumatra to British companies and to not post significant naval forces from Sumatra's ports without prior consultation with His Majesty's Government. The Cascadian government, in arranging the Sumatra Territorial Government, consulted with British authorities as promised, and President Lakeland signaled willingness to restore the Sultanate of Aceh to the northwest portion of the island should Britain push for the term (they did not). Additionally Lakeland and Burgess had given the British a free hand to decide policy in Africa and, over the course of the war, sufficient troops to bring their plans potential success. Although the Cascadians had not mobilized a large army for the war, upwards of 30,000 Cascadian Army Regulars had helped in the campaigns against Tanganyika. Lettow-Vorbeck had not been brought to ground until the end of the war, but his ability to raid effectively had certainly been hindered by the Cascadian troops provided for the campaigns in East Africa. For HMG, it was simply too late to renegotiate the division of spoils from the war. That Britain chose not to take over Germany's colonies was a source of some confusion in Portland; the decision reflected the push by many in the Liberal and Conservative Parties to give Germany further incentive to continue fighting the Bolsheviks.

Re-organization of the Cascadian Navy's disposition in Southeast Asia was necessary, with some heavy fleet units being recalled and fleet patrol routes altered to protect the new holdings.

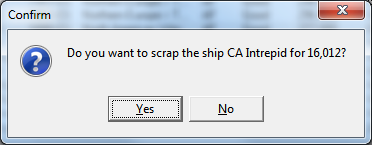

The armored cruiser

Intrepid was decommissioned and sent for scrapping, the start of new initiative by Admiral Garrett to keep the Navy's fighting power up.

The

Colossus' construction was halted to save money due to the budget cuts.

Despite the end of the war and the budget cuts, the Admiralty continued some of its planned construction program. Two new

Shepard-class destroyers, the

Hackett and

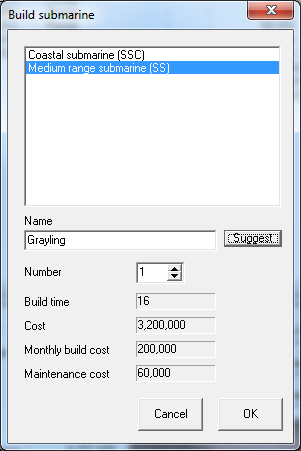

Williams, were ordered, as were two new submersibles.

The end of the war had been a national victory unmatched since the infant Republic had defeated the Mexican Emperor on the banks of the San Joaquin. But for one man, the victory did not feel like one…

The Garrett House

West Portland, Oregon

15 September 1918

The headline of

The Oreganian said it all. "

ARMISTICE SIGNED: CASCADIA TRIUMPHANT!" in big bold letters, with the Liberal-supporting newspaper happily touting the triumph of President Lakeland, Secretary of State Burgess, and the Liberal-Conservative Coalition Cabinet.

Admiral Garrett was sitting alone in his parlor as an early fall rainstorm seemed to herald the imminent onset of the wet season in the Pacific Northwest Coast. The gray pallor that the clouds cast upon the capital of the Cascadian Republic fit his mood as he read lines that, in better circumstances, would have filled his heart with pride.

"

It would be remiss for the nation to forget the true architect of this victory. It was the strategic genius of Fleet Admiral Stephen Garrett, the long time Chief of Naval Operations, that brought the Cascadian Navy and Royal Navy into harness together for the blockade that choked the life out of the German Empire. It is remembered by this newspaper that the Admiral's long life of service to his country has been met with success upon crowning success. His every effort has been a victory for our country and a testament to the clarity of his vision and drive. It is our expectation that the Governments that led the war will not forget this contribution…"

He threw the newspaper away while tears formed in his eyes. They were not tears of heartfelt appreciation. The feeling within him was hollow and bitter.

Never defeated? Fools! I have been defeated!, his mind raged. And then his voice joined in as he roared, "

This is not victory!"

He could already hear Mei-Ling's footsteps coming, undoubtedly to investigate his cry. She would find him weeping bitterly while slumped in his chair.

He had won a victory for his country, yes, and forever cemented his place in her history. But the price… the price he had paid had made this into the most bitter victory he had ever known.

Had he left the service before the war… had he retired, as he had thought of doing, as his wife had asked him to do, content in the four decades of loyal service to his country, then… then she might still be alive. Rachel might still be with him. And they would be enjoying the twilight years of their lives together, watching their children grow into adulthood and enjoying the grandchildren they had been given.

But he had remained at his post. The war had come. And in the end, it had been too late for them. Too late for her.

And too late for him.

There would be no retirement now. No rest from his labors. What would be the point? He'd already lost Rachel. He'd already lost his beloved.

The love of his life was dead. All that remained for the Admiral was his duty.

October 1918

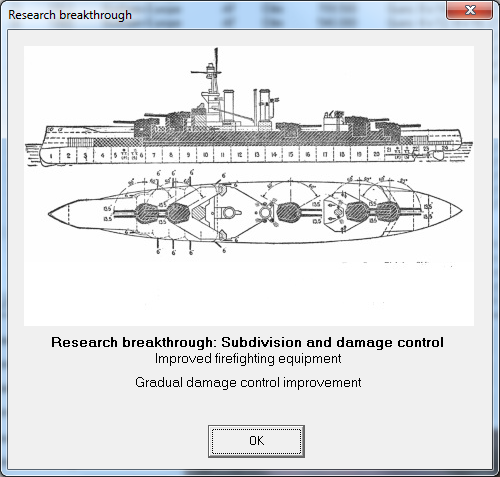

Naval Ordnance reported success in the implementation of new ballistic caps for shells and improved racks for depth charges.

November 1918

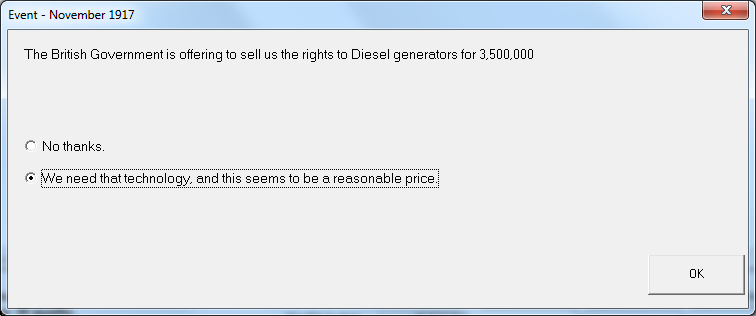

November 1918

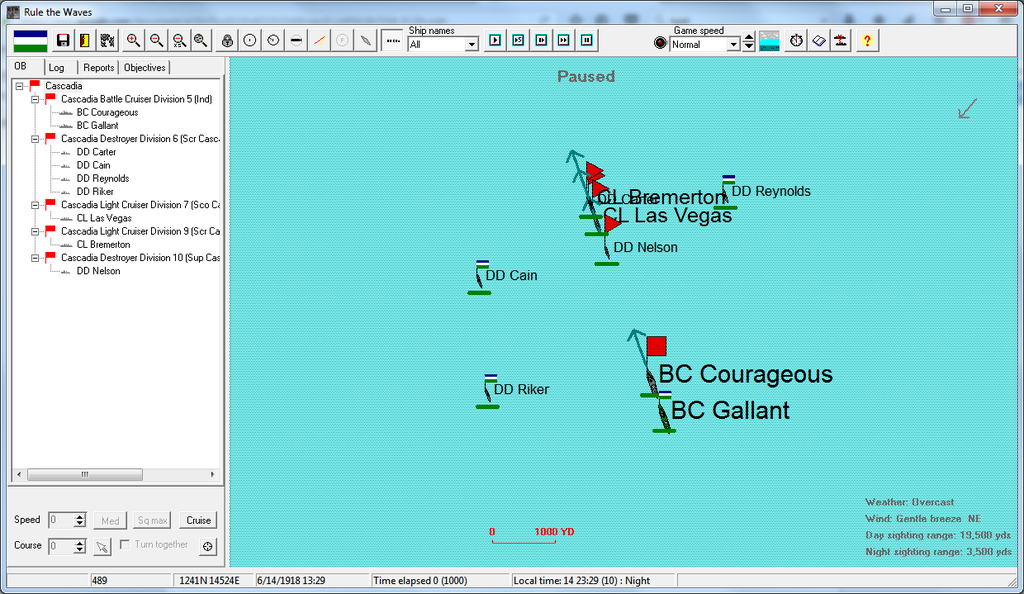

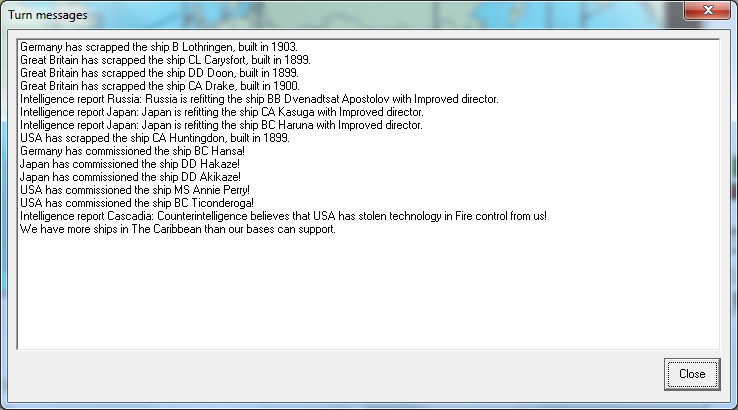

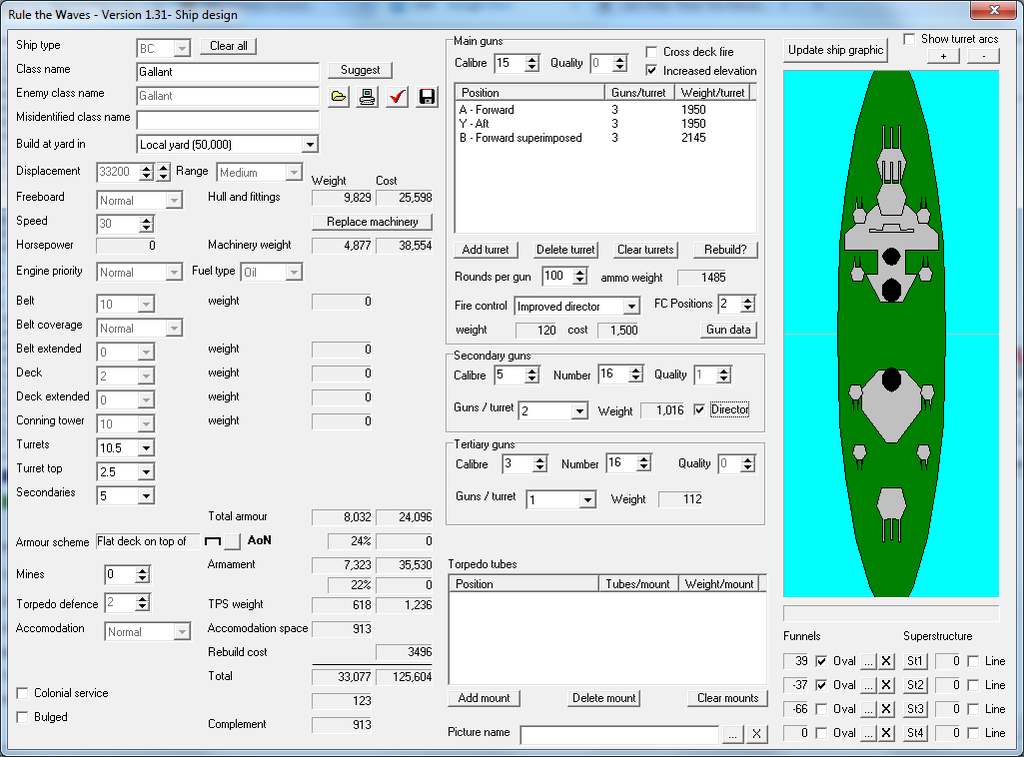

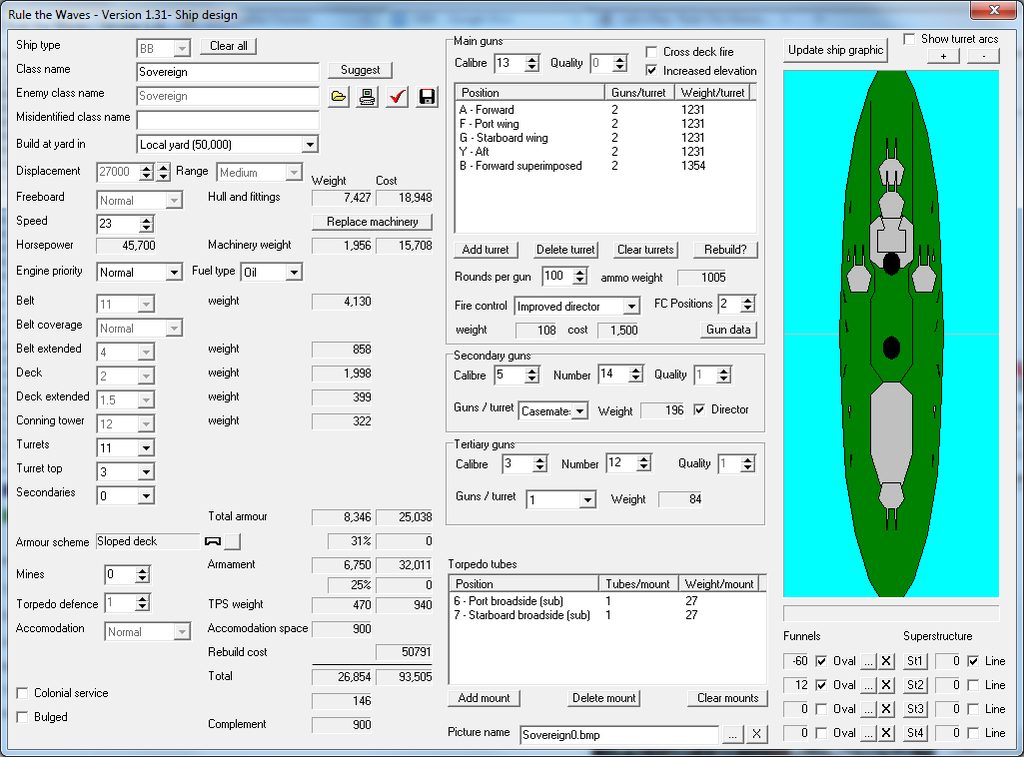

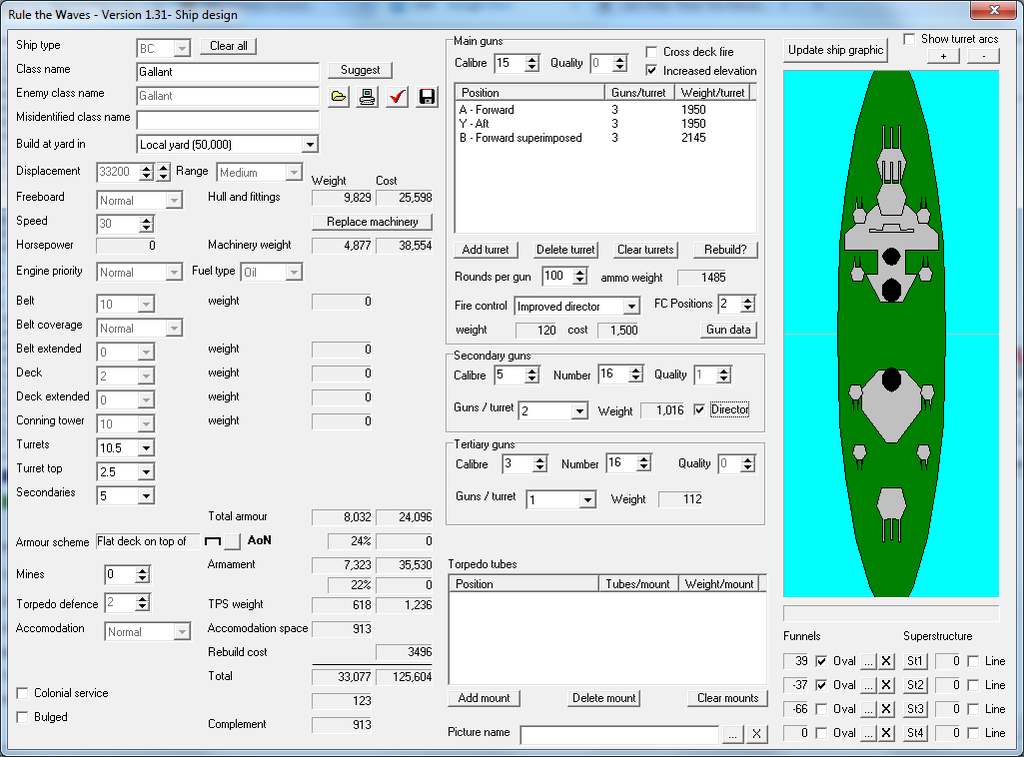

With the naval budget reworking complete, Admiral Garrett drove forward with a bold plan to completely refit the capital ships of the Navy. The

Gallant and the

Sovereign were sent into the yards for refitting work.

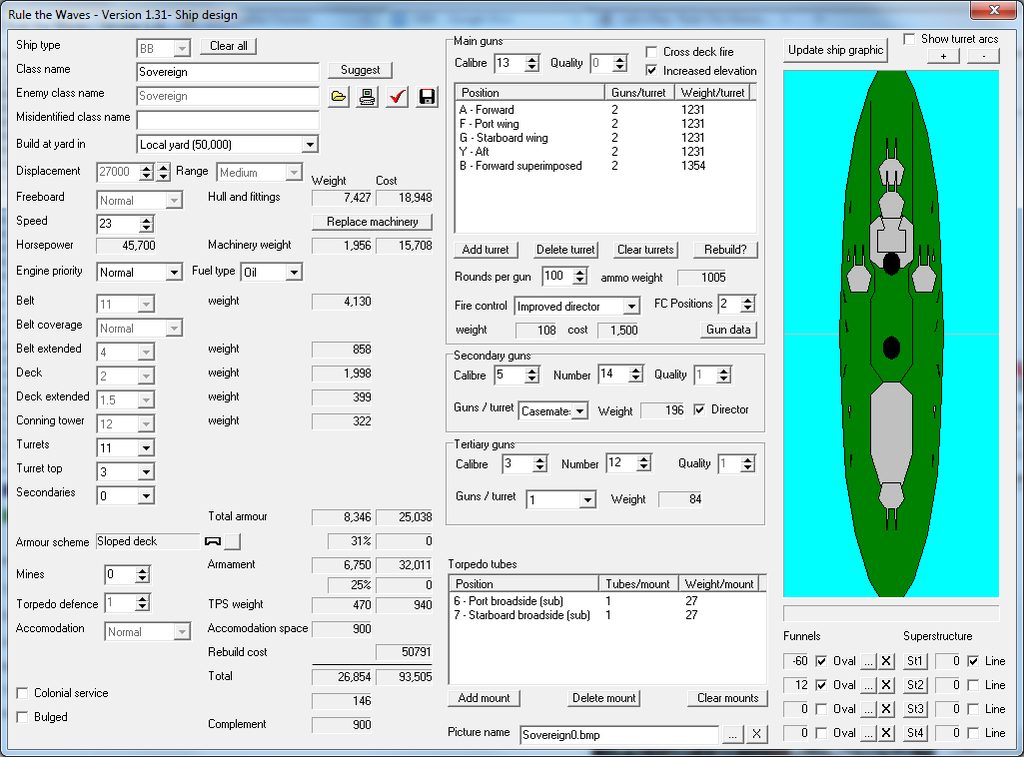

Gallant would receive new primary and secondary fire-director gear and turret elevation gear.

Sovereign would be virtually rebuilt, with the latest 12" guns, new machinery for 23 knot flank speed, and updating of the firing director and turret elevation gear.

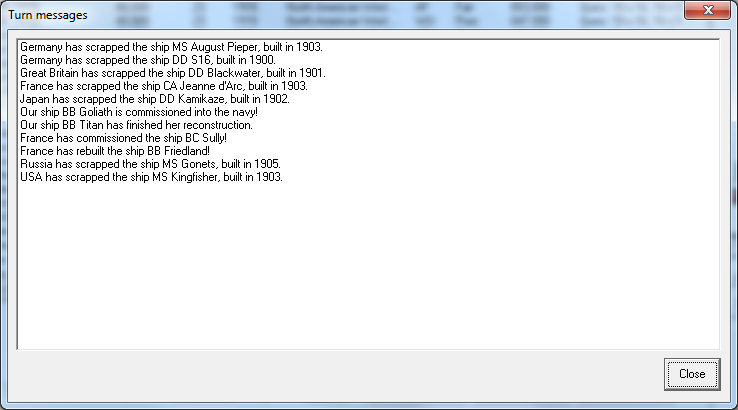

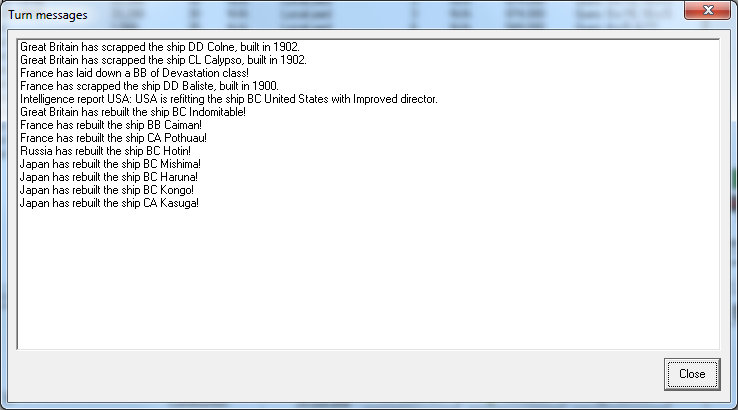

The refitting extended to new ships. During the month the

Goliath was commissioned and the

Titan finished her first refit. Immediately both ships were put back into the yards to be refitted with directors for their secondary guns and to install increased elevation gear for their main batteries.

The restructuring of the naval budget also allowed for the resumption of work on the

Colossus.

In statements to the national press and to the Parliamentary committees on naval affairs, the Admiral acclaimed the need to overhaul the Navy now that the war was over. Old hulls needed to be reworked for new jobs or, if such was not financially or physically feasible, decommissioned and scrapped.

Another four

Shepard-class destroyers were ordered: the

Kaiden,

Daniels,

Moreau, and

Adams

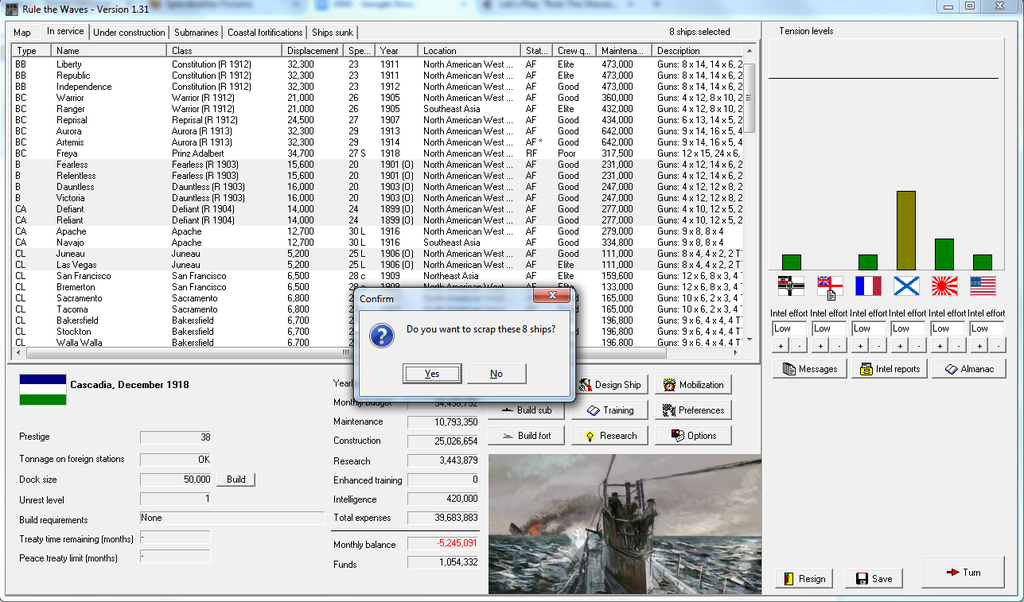

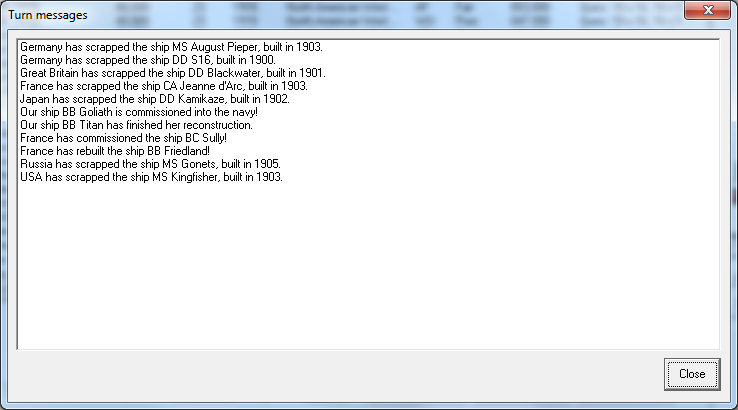

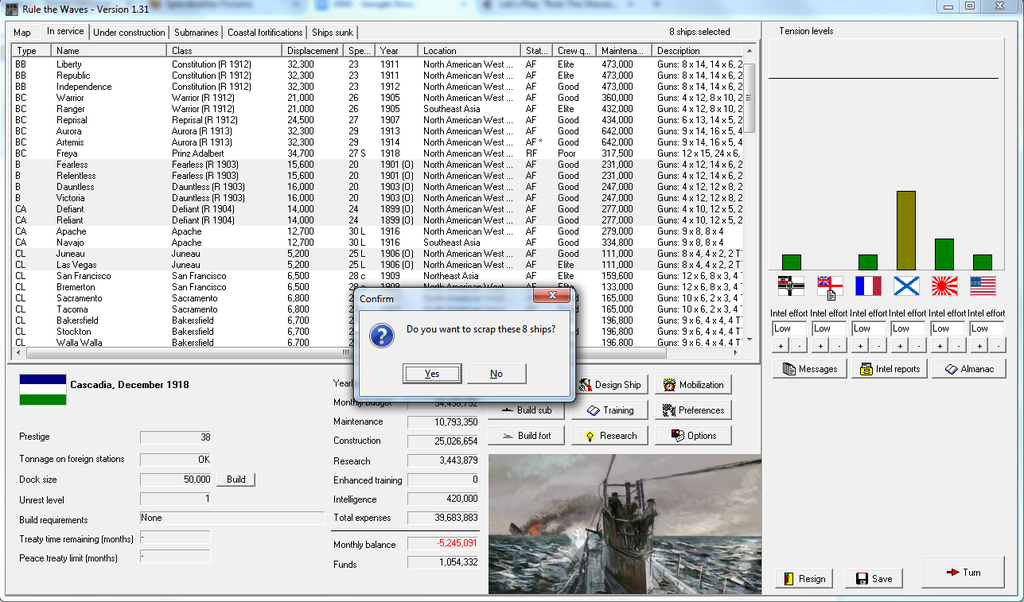

December 1918

December 1918

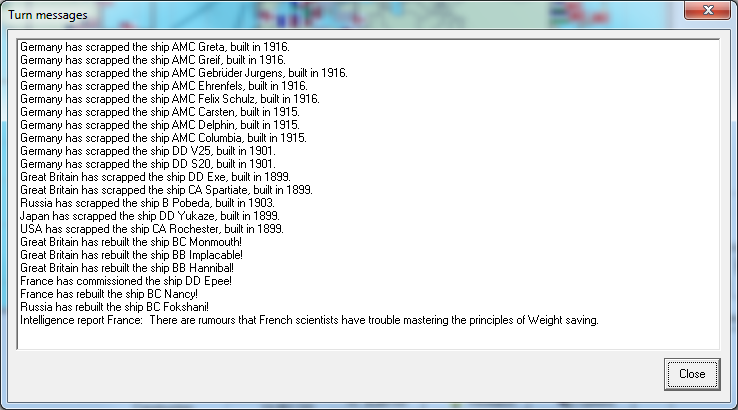

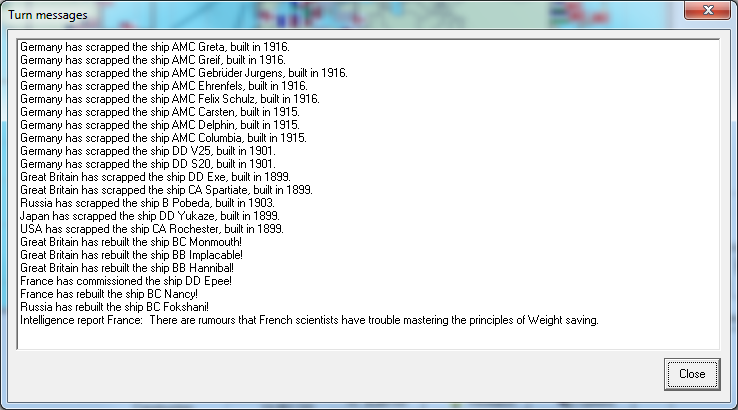

The 1919 Naval Refitting Plan in the Admiralty goes into effect with immediate orders for a mass decommissioning and scrapping of old surplus warships. Among those vessels sent to the scrappers were all four pre-sovereign battleships of the fleet -

Fearless,

Relentless,

Dauntless, and

Victoria, the armored cruisers

Defiant and

Reliant, and the raiding cruisers

Juneau and

Las Vegas.

The

Juneau is ultimately the only ship of the group saved from the scrapyards, as her namesake city raised the funds through popular subscriptions by city residents and former crewmembers of the plucky old cruiser to purchase her and tow her into the harbor to become a museum ship.

Financial considerations require the brief suspension of

Sovereign's comprehensive rebuild.

To further save funds, the

Constitution,

Independence,

Warrior, and

Reprisal had their activities reduced to a level only sufficient to maintain partial crew readiness for action. Admiral Garrett defended the move on the grounds that war was unlikely for the next several years.

Additionally, Admiral Roger MacCallister announced his intention to retire. Although he had been awarded the Cross of Victory 1st Class for his effort in the war, many of his subordinates and superiors felt that he had behaved with excess caution during the actual battles of the war, denying the Navy any hope of a decisive naval victory that might have ended the war more quickly. Admiral Garrett invited him to a retirement dinner at the Admiralty and praised his work in maintaining the blockade and solid relations with the Royal Navy.

His replacement as commander of the Battle Fleet was Vice Admiral John Litchfield, who picked 2nd Battle Squadron commander Rear Admiral Phillip Wallace to be his Chief of Staff. Both men were promoted one grade to match their new positions.

Additionally, the old 500t and 600t destroyers of the

Hull and

Blake-classes were ordered into mothballed status. Admiral Garrett supported a new report from the Office of Naval Design and Procurement calling for the old ships to be relegated to coast patrol and sub-hunting duties in any future wars if they were not scrapped..

Constitution, Independence, Warrior, Reprisal ordered into Reserve Status. Hull and Blake-class DDs mothballed.

To continue the bulking of the Navy's destroyer fleet, another two

Shepard-class destroyers were laid:

Pressley and

Donnelly. Additionally, two more submersibles were ordered to further replace wartime losses.

The Garrett House

The Garrett House

West Portland, Oregon

25 December 1918

Everything was as it has always been. The tree was up, candles and lights for the holiday, presents readied and exchanged. Christmas had come to the Garrett Family and, for the first time in four years, it had come with Rafael present with his wife.

But now there was another face missing, and this was one that wouldn't be coming back.

They tried nevertheless. Gabriela, with her hair now cut almost scandalously short, was as lively and boisterous as she could be. Sophie was striving to stand in as hostess with the same elegance and poise her mother had managed in her prime. Anne-Marie helped as much as she could given her need to watch her children, especially the infant David who, as infants often did, alternated between sleeping and crying. Georgia was radiant and blissful now that she had Rafael on her arm. Whatever problems the war had caused with their marriage, his return with the

Constitution had smoothed them over.

But nothing could hide the fact that this was the most somber family Christmas in years.

What else could it be, this first Christmas after Rachel's death?

The family was assembled at the table as always. The Admiral sat at its head, his usual place, and to his right sat Sophie, acting as lady of the house. Blessings were given and the meal commenced. The talk highlighted the end of the war and Raffie's return; his awaiting a position at the Naval Staff College prompted Thomas and Anne-Marie to invite Raffie and Georgia to live in Vallejo if it came to pass, since the College was located at Mare Island.

"How are you doing in the provincial legislature?", Raffie asked his younger brother.

"It's been an education," Thomas answered. He scratched at the edge of his eyepatch.

"Will you run for Parliament?", Sophie asked him.

Thomas turned his head toward Anne-Marie, who was fussing with little David to get him to eat. "I've promised not to uproot everything until David is a little older," he admitted. "I won't run before '20, if I do at all."

"And what about you, Sophie?", asked Raffie. "You're out of school soon, right? Found anyone yet?"

She smiled gently at that. "No. Nobody worth my time," she said. "And I've actually been thinking of traveling to Europe soon. Now that the war is generally over, I'd like to see some of the cities grandfather served in and maybe write about them."

"My sister, the lady of learning," Rafael remarked. "Send me what you write and I can see if any of my editors are interested."

"I may do that."

For a moment there was no further conversation. Gradually it dawned on the others that the Admiral had barely touched his food.

"Father, what about you?", Rafael asked.

"Hrm?"

"Well…" Rafael gave a worried look to his siblings. "I remember Mother writing that you intended to retire when the war is over. But everyone in the fleet is saying you're staying on."

"I am," he answered simply.

The table went silent.

It was the Admiral who broke the silence. His children deserved to hear it from him.

"I told your mother I would retire at the end of the war," he explained. "And I had intended to retire at the end of 1915, had the war not intervened."

"But you won't now?", Thomas asked.

"No. Now that your mother is gone, there is no point," the Admiral informed them. "I will remain at my post until I am no longer capable of performing my duties."

"But…. Papa, you deserve to rest," Sophie insisted. "Living through the winters here can't be good for your health. It's what took Mama."

"The grandchildren would love having you living in Vallejo," Thomas added.

"Perhaps. But my decision is made. I'm not retiring yet." His voice was curt. Unintentionally so. But he wouldn't let himself question this.

"What about me?"

Everyone looked to Gabriela.

"What is it, Gabbie?", the Admiral asked.

"Don't I matter to you too?", she asked. "If you retire, we can go live somewhere nicer. We can travel."

"You have schooling to finish first," he reminded her. "Then we'll talk about travel."

Gabriela frowned and looked away. She looked hurt. "Does your job matter more than I do?"

Again, silence descended upon the table.

"You are my daughter, Gabriela, and I will always love you," he said. "But I have a duty to the country, and to the Navy."

"And that's more important, isn't it?", she said. Her voice was harsh now. "Maybe you should just be honest and say that the Navy is more important than your family. It's how you treated Mother, after all."

"Gabbie!", Sophie hissed.

Gabriela let her utensils clink in her half-finished plate. "I'm not hungry," she grumbled, standing up.

"You have not been excused," the Admiral grumbled.

An almost mocking tone came from Gabriela's voice when she asked, "Then may I be excused,

Admiral?"

The old man closed his eyes and sighed. "Yes," he said weakly. "You may."

And before her startled siblings and sisters-in-law, Gabriela stormed out of the dining room.

After she was gone, the Admiral opened his eyes again, as if it were okay to do so. He looked over his wounded family. "Gabriela has your mother's fire and my stubbornness," he said. "And losing Rachel has been difficult for her. Please, pardon your sister." He set his fork into the cut of goose on his plate. "After all, it is Christmas."