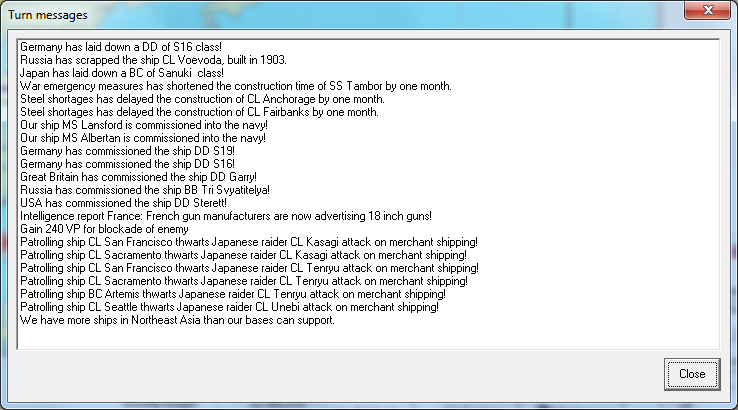

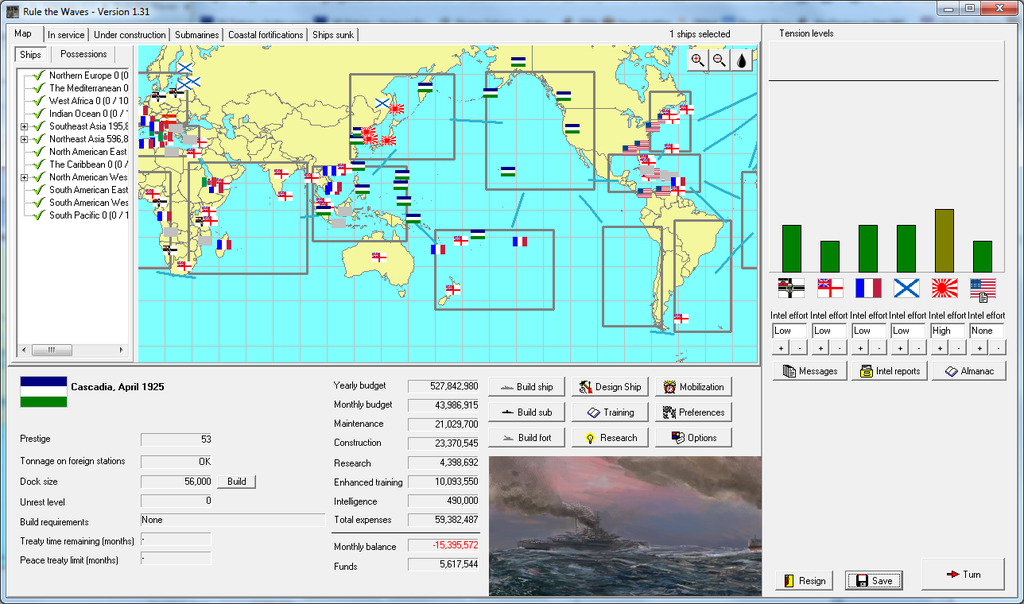

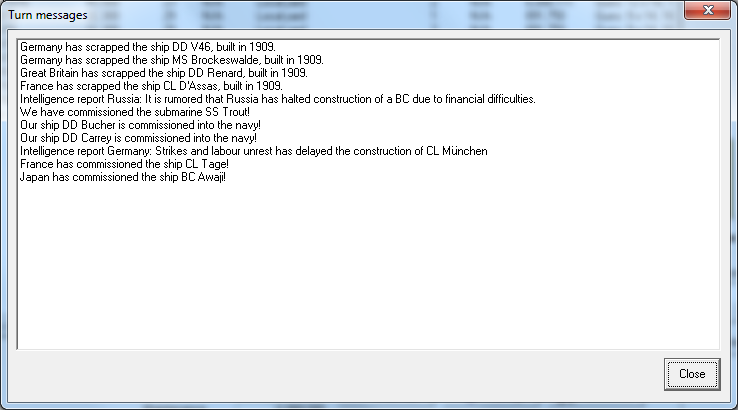

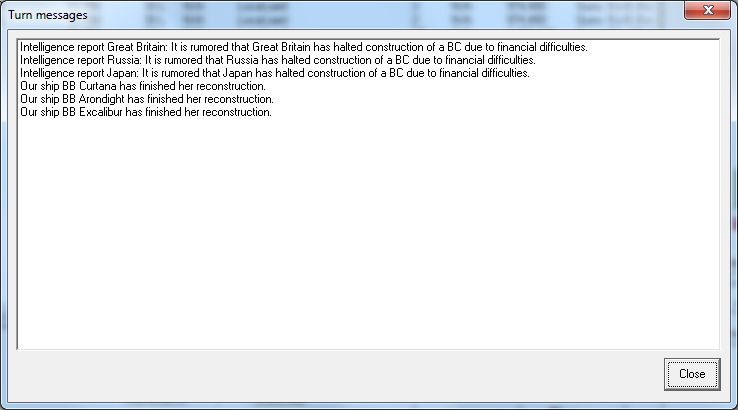

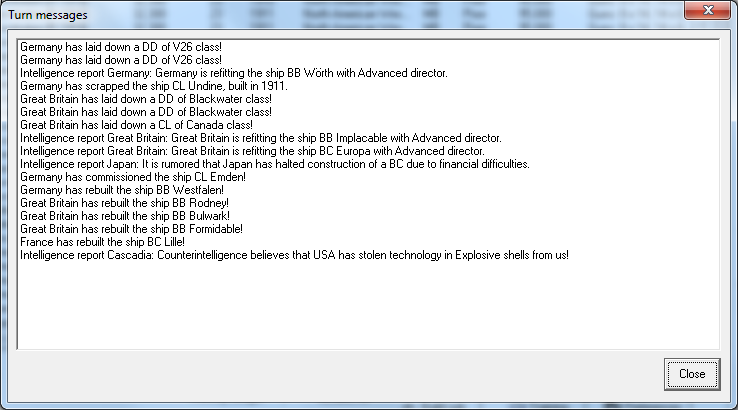

Even with the onset of the war, Cascadian industrial power continued to grow, fueled by a rising population, increased industrialization, and the growing prosperity of the populace.

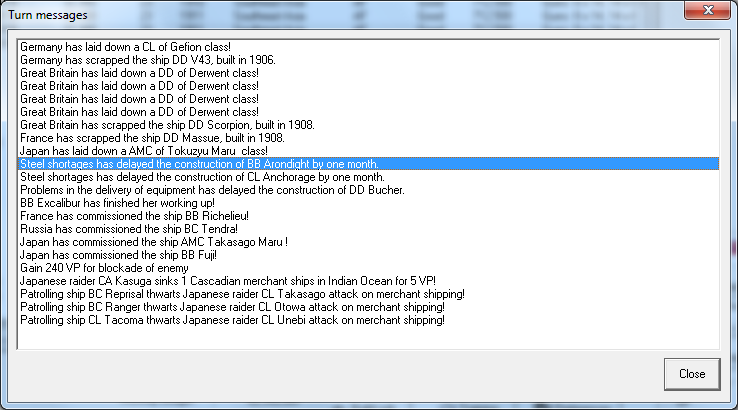

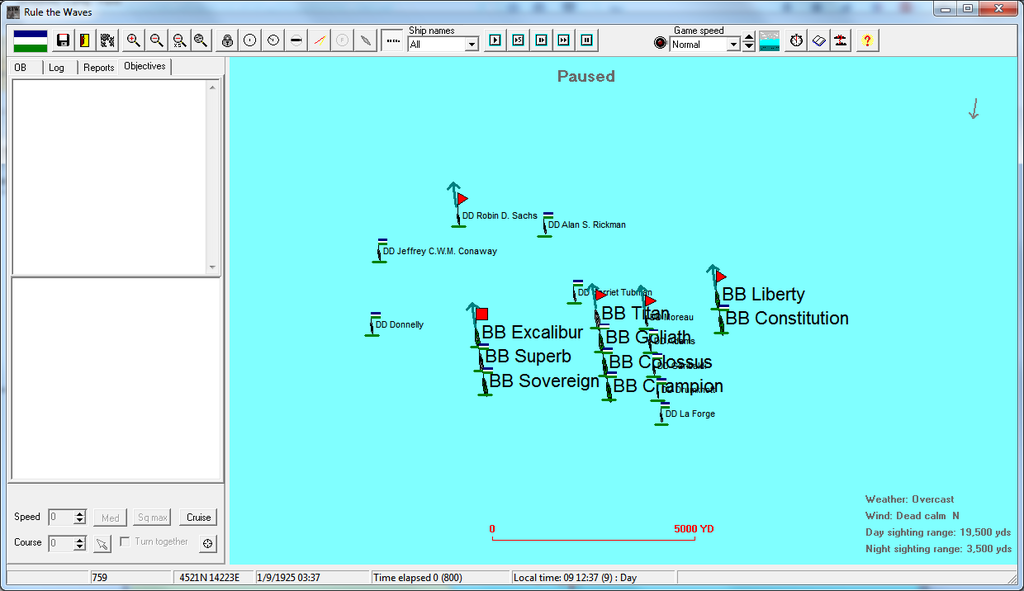

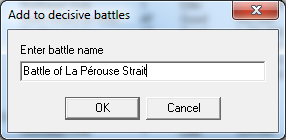

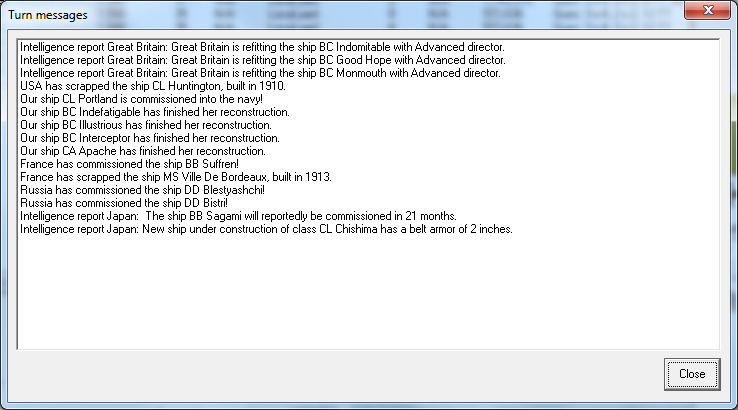

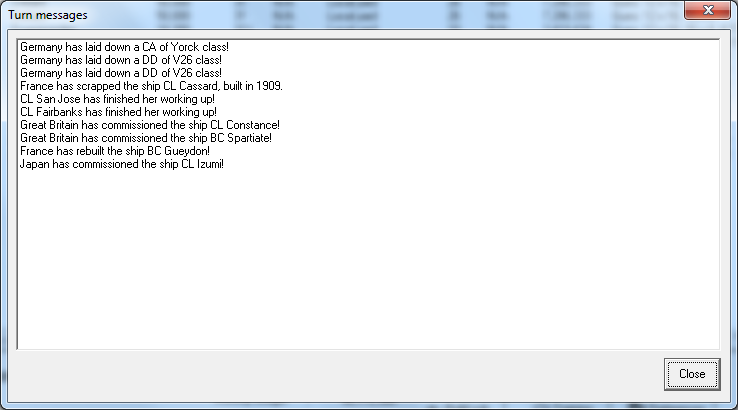

The Excalibur was commissioned. The largest battleship in the world at that time, the Navy would be further pleased when her trials showed that while she had been designed for 23 knots as a maximum speed, she was in fact capable of 24 knots.

The Soviet Government protested the boarding of a Russian ship near Liaotung by Cascadian naval forces.

Russia tension to 7

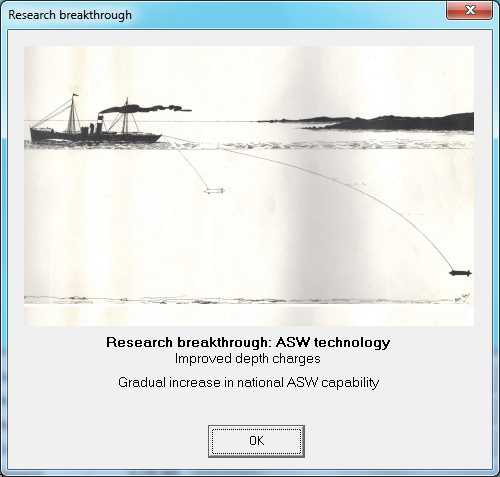

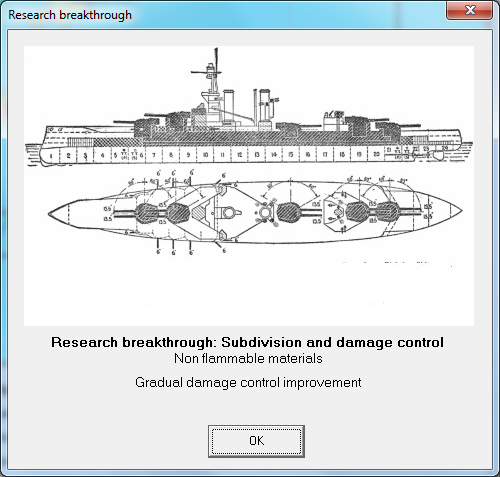

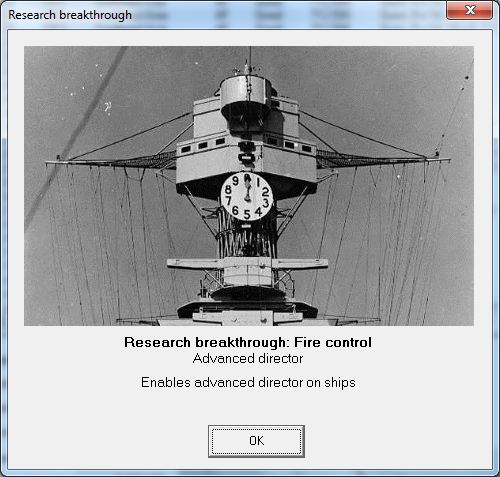

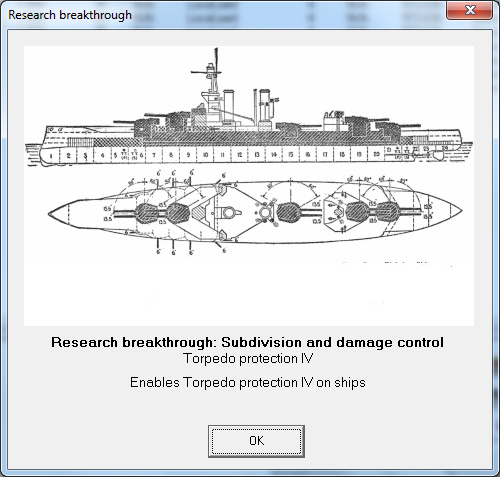

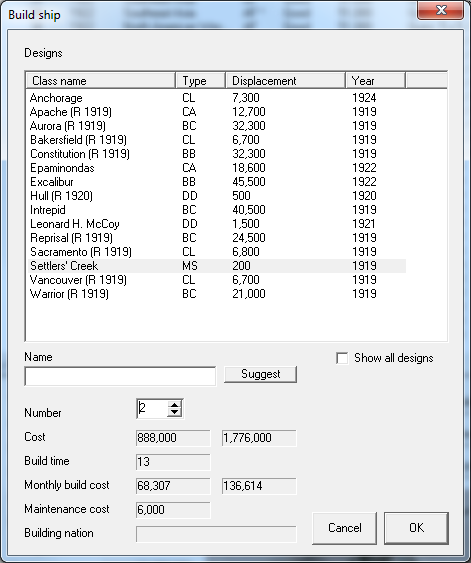

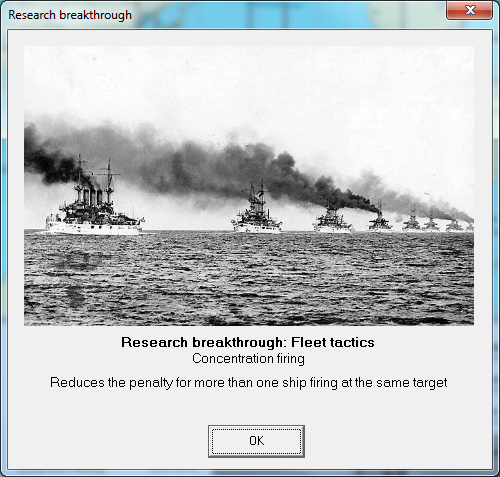

Burleigh & Armstrong designers finished work on a new mine-laying submersible design. The Admiralty ordered four from the contractor. Admiralty gunnery experts reported progress in studying on firing patterns and better methods of concentrating fire.

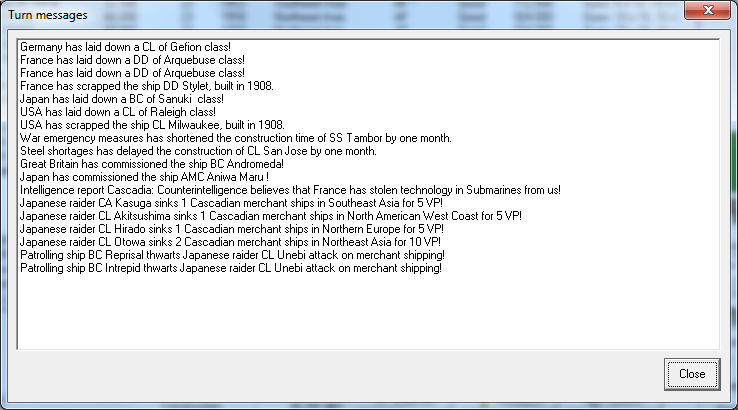

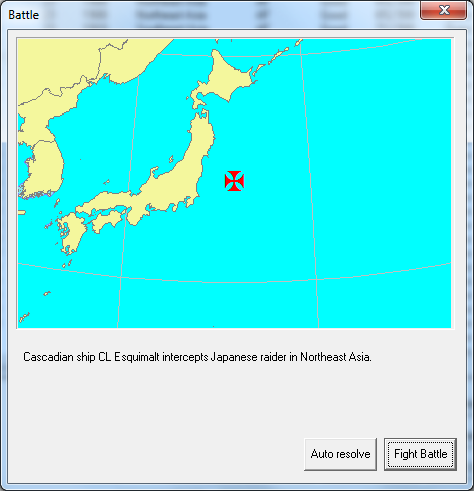

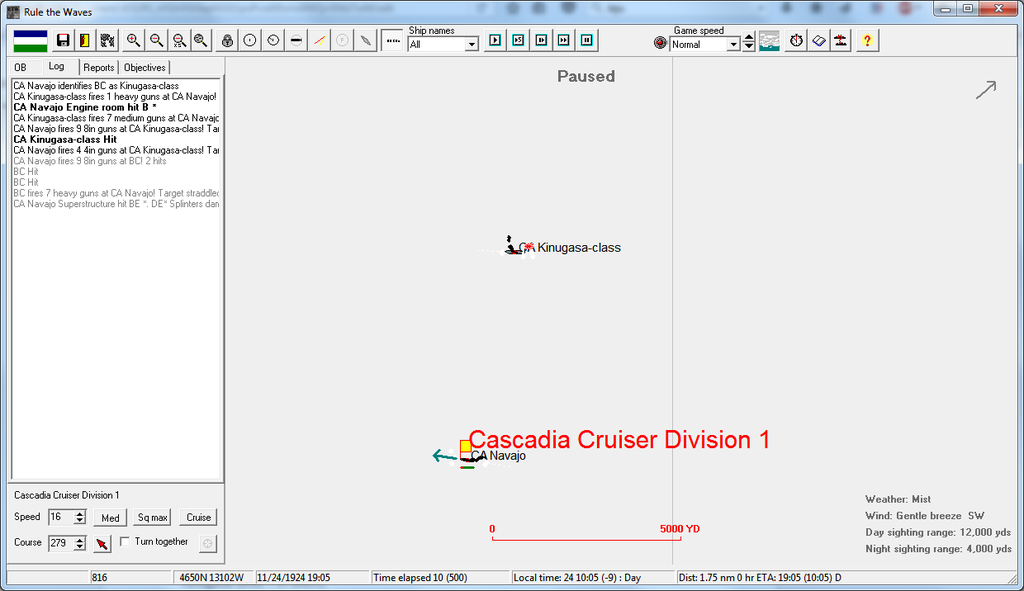

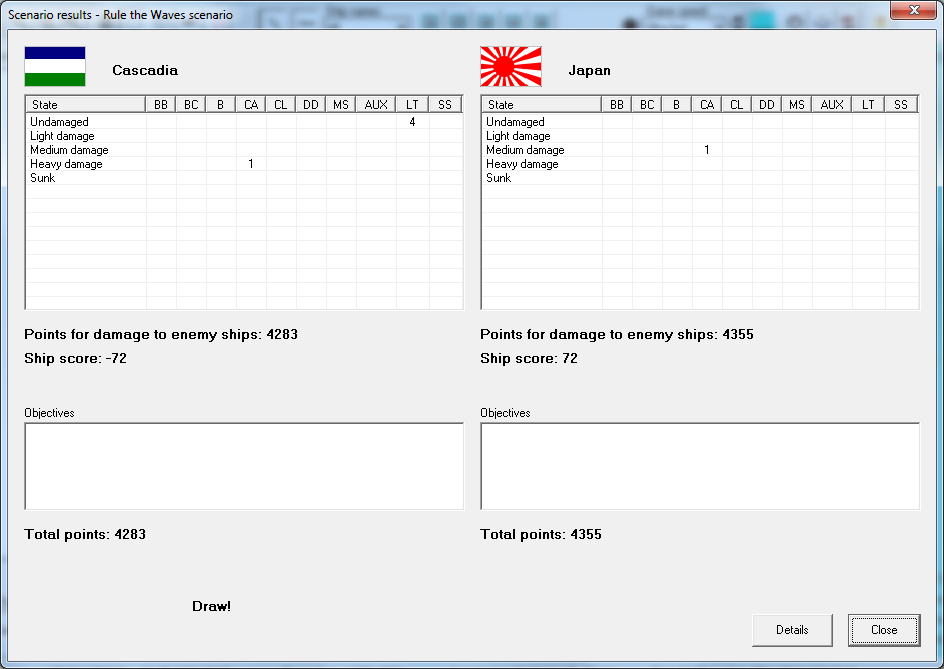

The Cascadian submersibles had another decent month. Twelve Japanese ships were sunk at the cost of another Cascadian sub. The Japanese ratio was worse: 2 subs lost for three Cascadian ships. The Kasuga and Kinugasa each sank a Cascadian vessel in East Asian waters.

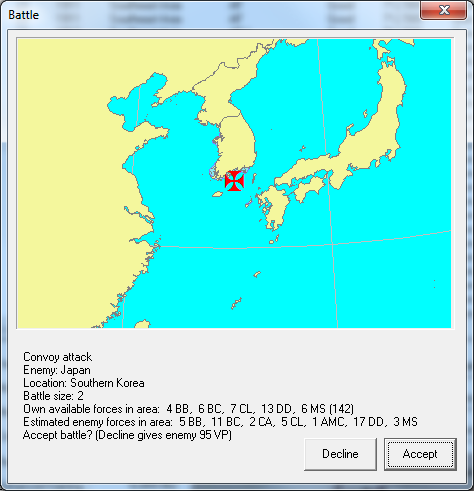

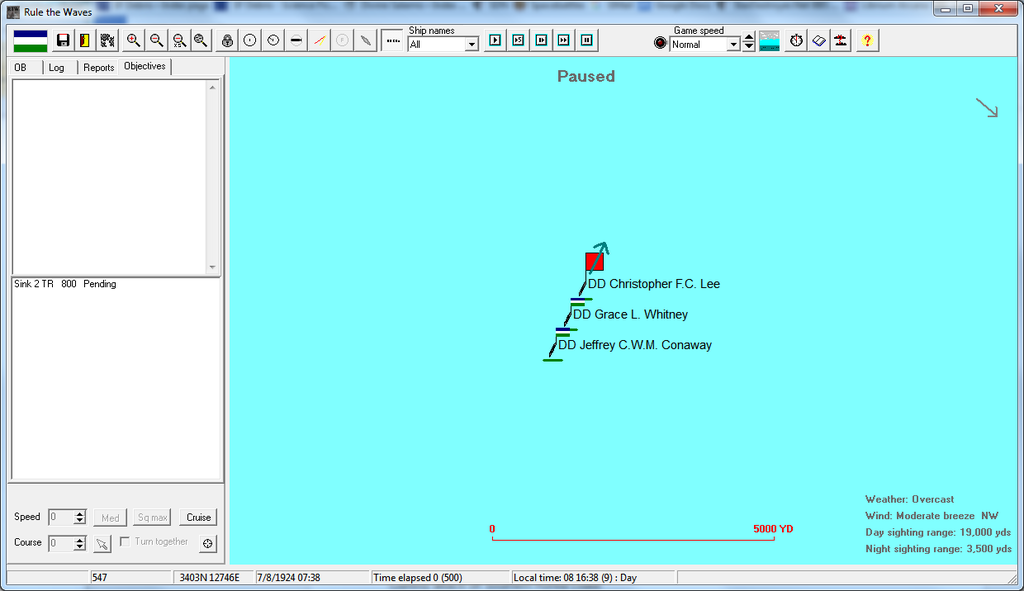

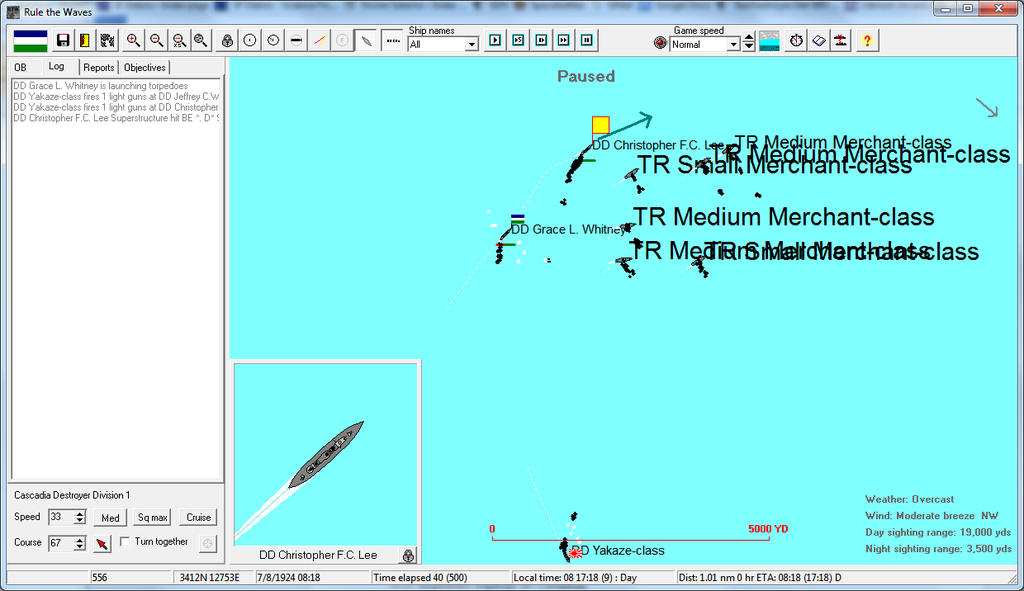

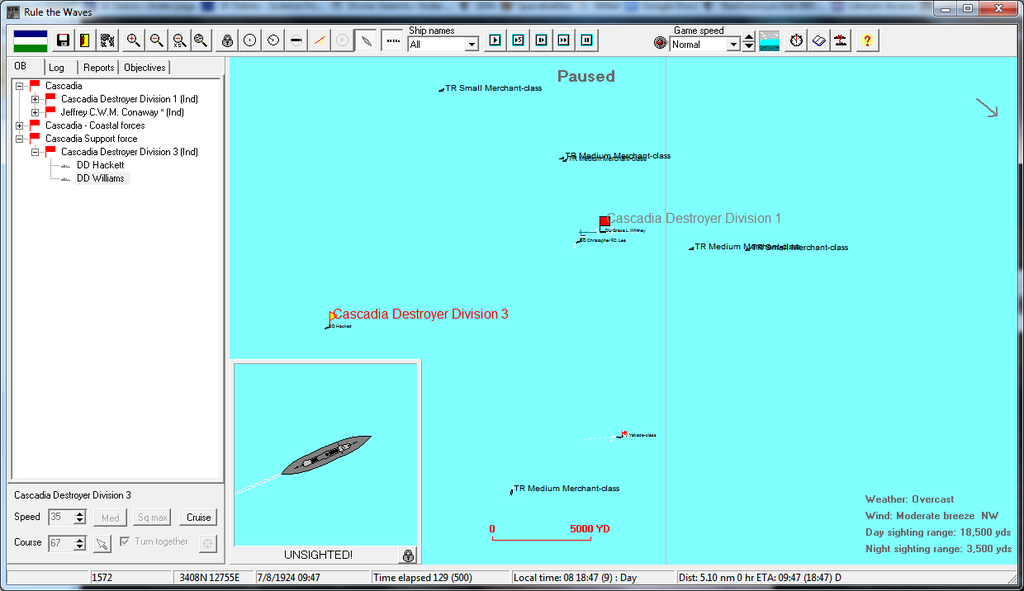

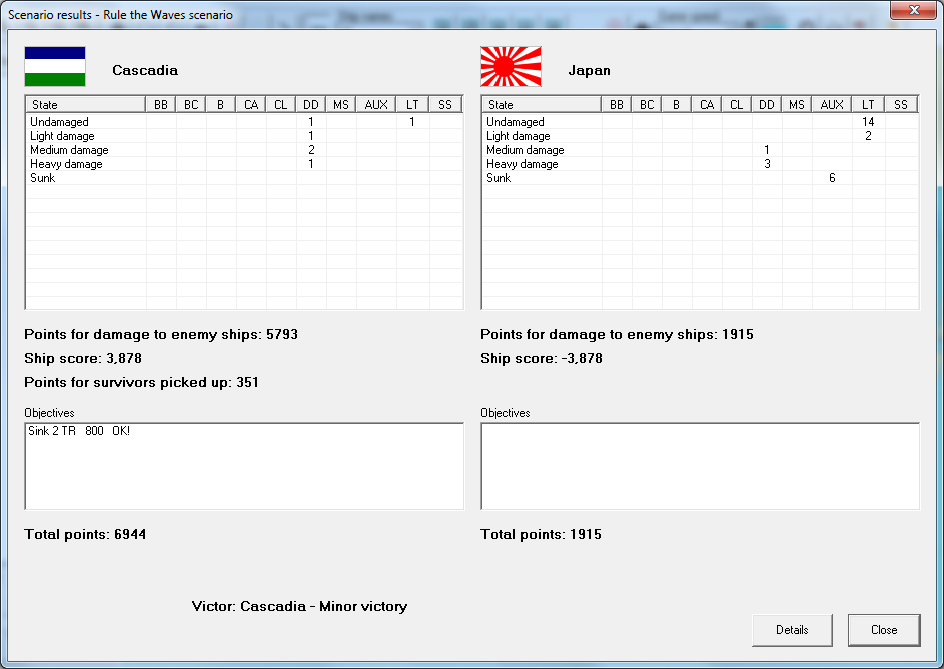

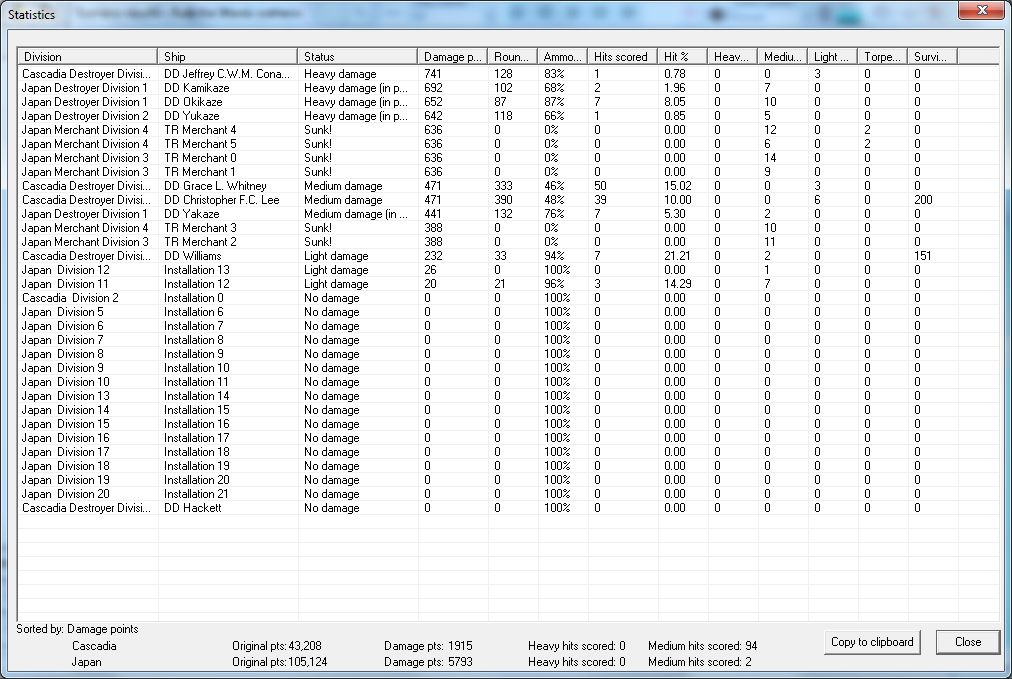

On the 8th, the Lee, Whitney, and Conaway raided Japanese shipping off the southern coast of Korea.

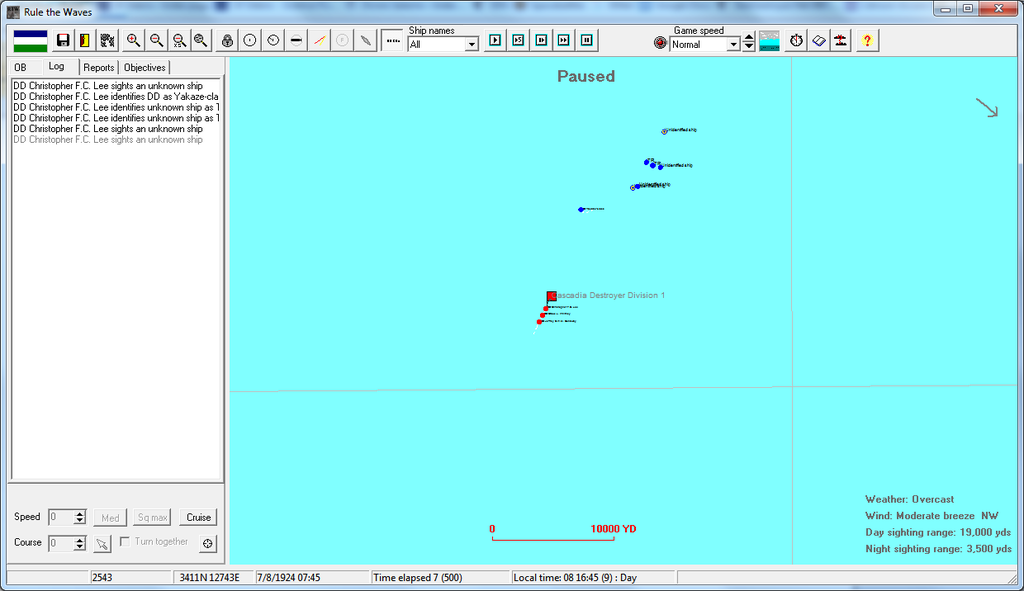

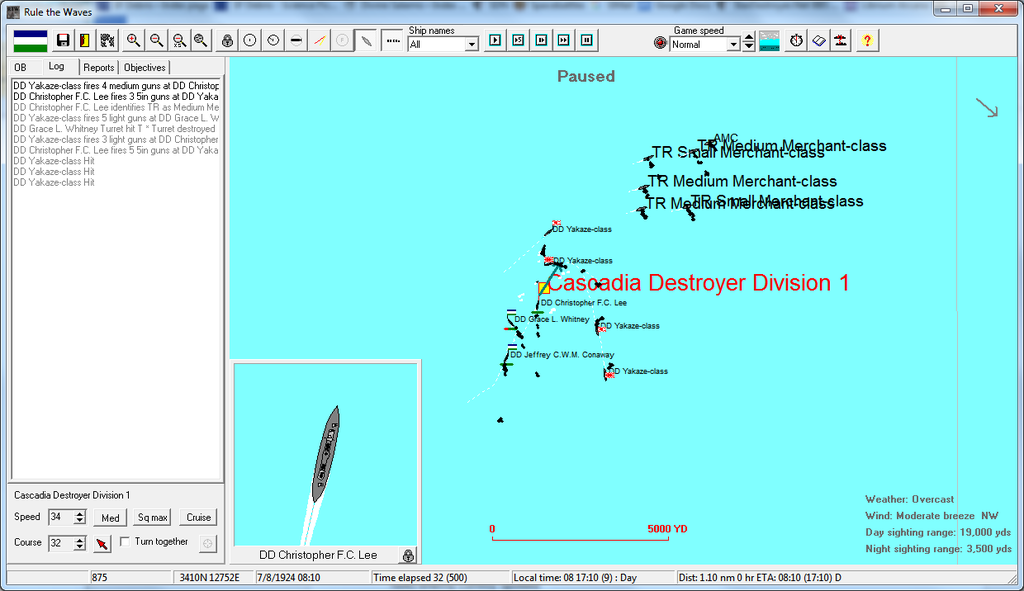

They spotted the enemy convoy at 1645 and moved to engage. The Japanese screening force was made up of four Yakaze-class destroyers.

The two sides inflicted damage upon one another as the Cascadian destroyers raced to break through to the convoy.

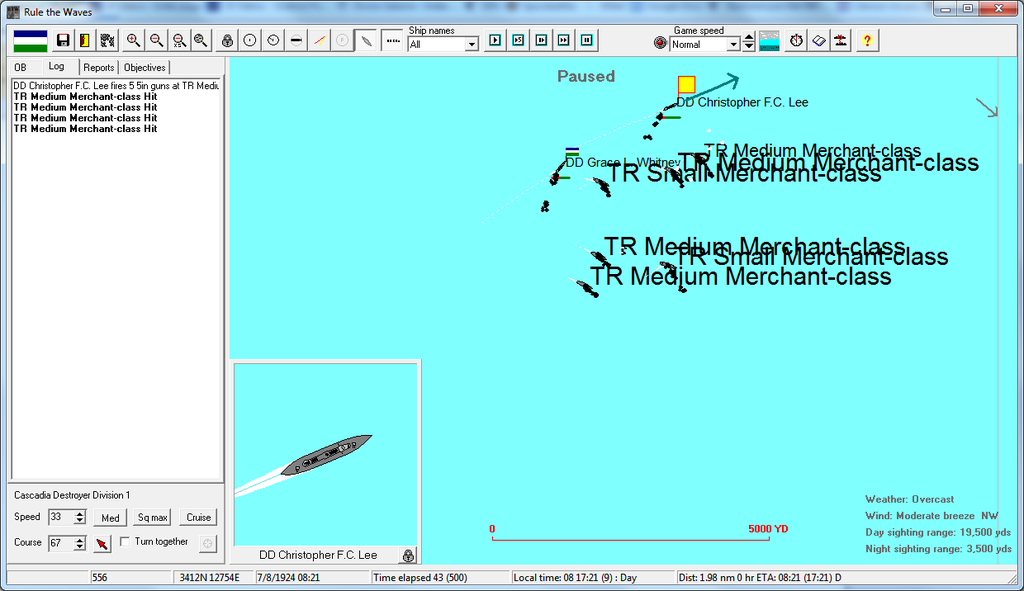

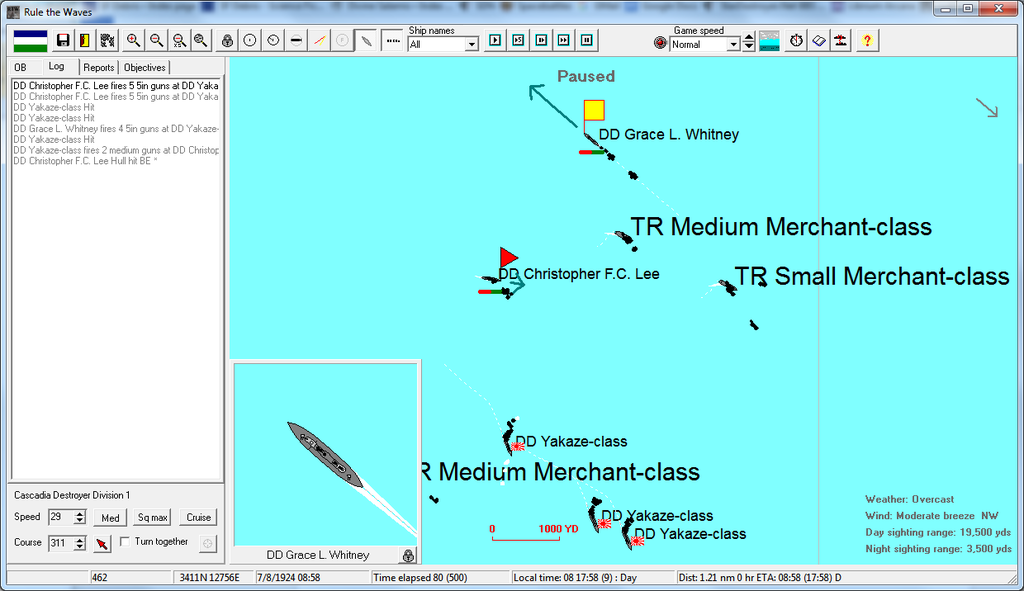

At 1711, a Japanese shell caused one of Conaway's torpedo mounts to explode. Heavily damaged, the Conaway detached from the division and fled toward Tsingtao. Through bold maneuvering, the two remaining Cascadian destroyers got past their foes and starting shooting up the Japanese convoy.

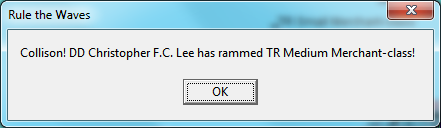

While maneuvering among them, a miscalculation by Lee's commanding officer led to the destroyer slamming into a transport, momentarily knocking the ship's engines out of action.

Lee's guns kept firing, however, and for nearly an hour after the ramming her guns kept the Japanese at bay while the Whitney finished off the convoy.

By 1840, the Lee regained power, but the two ships were still outnumbered. At this point, the Williams steamed into the fray, with the Hackett not far off. The heavily-damaged Japanese ships never recovered initiative - they fled, most heavily damaged, by the time night fell and the engagement came to an end.

The Battle of July 8th was a Cascadian victory, even if none of the Japanese warships were sunk. The Cascadian ships, outnumbered early on, inflicted greater damage on the foe and annihilated the convoy. The Japanese were humiliated, and more than that, had reason for intense worry: the battle and its outcome showed that the Japanese Navy could very well lose control of its most vital sealanes to the Cascadians. If this occurred, Japan's days were numbered.

As news of victories poured into the cities of Cascadia, the stirrings of opposition in the populace died down. War bonds were being bought with enthusiasm by the population - the July issue, which earned the nation nearly $400 million Cascadian, had been joined with the story of the "Last Stand of the Warrior", and an emotional written appeal from Captain Michaels and Admiral Phillip Wallace to the populace on the fate of the Cascadian Navy's old pride.

Wallace's appeal was considered particularly poignant, appearing in newspapers across the country as an obituary to the Warrior.

"Strange as it may seem to write an obituary for a ship when so many lives were also lost that day, I feel it incumbent upon me to do so. Anyone who knows the sea will tell you that on some level ships are alive, they have souls and hearts. Warrior lived up to her name, fighting in the best traditions of our, or indeed any Navy, standing in harm's way between friend and foe.

Of all the ships I have commanded or served on, she held a special place in my thoughts. She was my first command, and before that I was her first Executive Officer. Together we made history as the progenitor of a whole new type of warship, as significant in her own way as the later Sovereign would be. She was magnificent, fast, powerful, and she most definitely had a soul.

There were times, when we maneuvered at full speed, when we fired her guns in our drills, when I could feel her structure sigh in contentment, doing what she was built to do. She answered every trial, surpassed every expectation, and performed beautifully whenever called upon to do so.

Of course, all good things must come to an end. This was the last battle of the fabled Warrior, and unlike so many old ships, she went down gloriously, defiantly, firing to the last, rather than the slow, sad process of being hauled to the breakers. Some have said she should not have been there, that an old and outdated ship had no purpose.

Those people are wrong. Despite her loss, that brave ship charged an enemy that considerably outgunned her, that outpaced her, that was better defended than her in order to save a vital convoy and thousands of lives. She, they, succeeded, inflicting damage on the enemy and buying time for other ships to arrive and defeat the Japanese. Those thousands of people are alive now because that brave old ship chose to stand and fight.

She was a ship that made history, and history will remember her fondly. Myself and all the others who served in her will recall those heady days with a smile, and raise their glasses in salute. We can take comfort in knowing that she was avenged, that many of her crew were saved and that even in death, she was triumphant.

Farewell Warrior, and thank you for standing in harm's way."

Indeed, in Hollywood, Lower California, producers of new "mover" films, led by industrialist and inventor millionaire Ignacio Blackstone Varrick, were busy filming a new production called "The Last Stand of the Warrior", a production destined to become a key piece of Cascadian cultural history.

Faced with this enthusiasm, the dove factions of the major parties lost traction in Parliament, even as the 1924 Presidential election kicked into gear. Alonso Muniz was running on what was effectively a Hawk ticket - the Conservatives and Populists endorsed him, as did Hawk Democrats and Hawk Liberals. The Communists pledged the mostly unknown Paul Noel, a Party speaker who had lost election bids to local and provincial governments, and the Socialists joined Dove Liberals and Dove Democrats in promoting a campaign for Senator Karl Green, the effective leader of the Opposition in the Senate. It was patently clear as the year went on, however, that neither candidate had much hope in defeating Muniz, short of a military disaster.

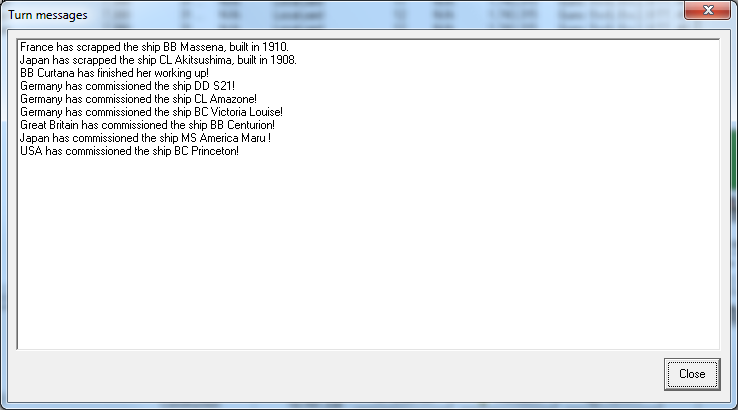

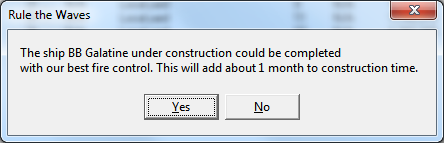

The increased naval budget had also, by this point, permitted construction on the Galatine and Curtana to resume; all three remaining Excalibur-class ships were expected to be in service by the midway point of 1925.

Unrest down to 1

The Japanese attempted another elaborate offensive in Manchuria, starting on July 10th. Days of artillery bombardment, infiltration tactics, and the first Japanese use of armored "tank" vehicles won them another mile of penetration in some spots. But their tanks broke down, their infiltrators had suffered enormously against the picket foxholes, and the bombardment had allowed the Cascadians warning to shift troops to reduce those in the forward, vulnerable trenches in favor of enough force for a major counter-attack. This developed on the 11th. By dawn on the 12th, most of the Japanese forces had been pushed back to their starting points, and about four thousand Japanese troops in the furthest penetrations were actually encircled and forced to surrender over the coming days.

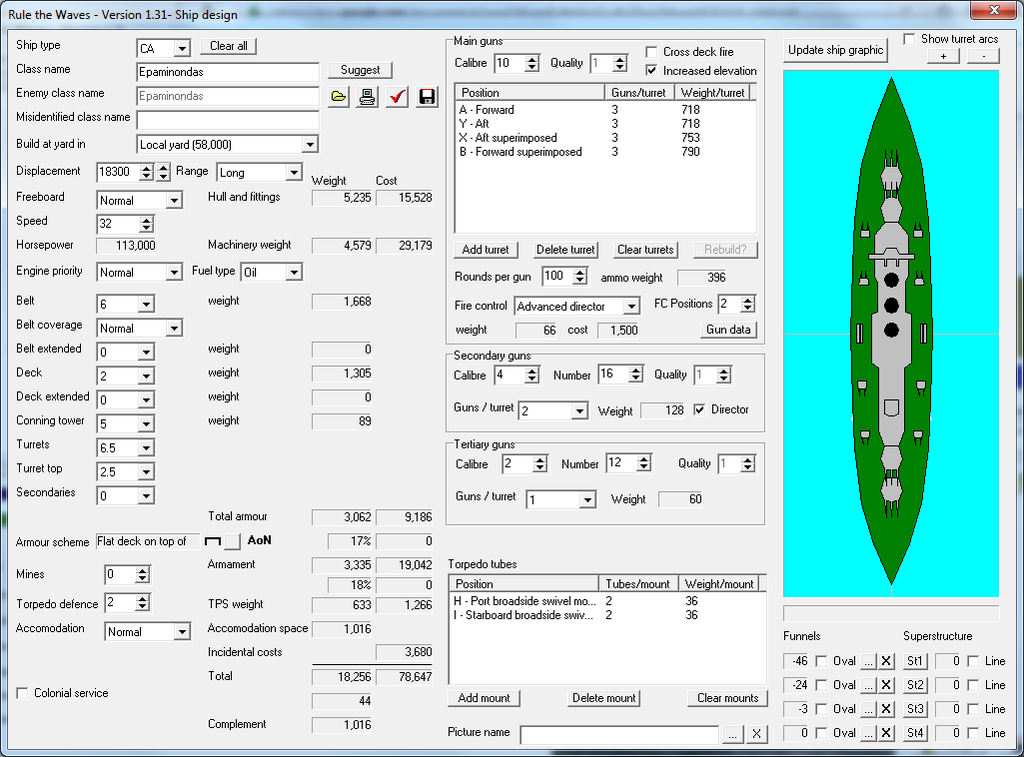

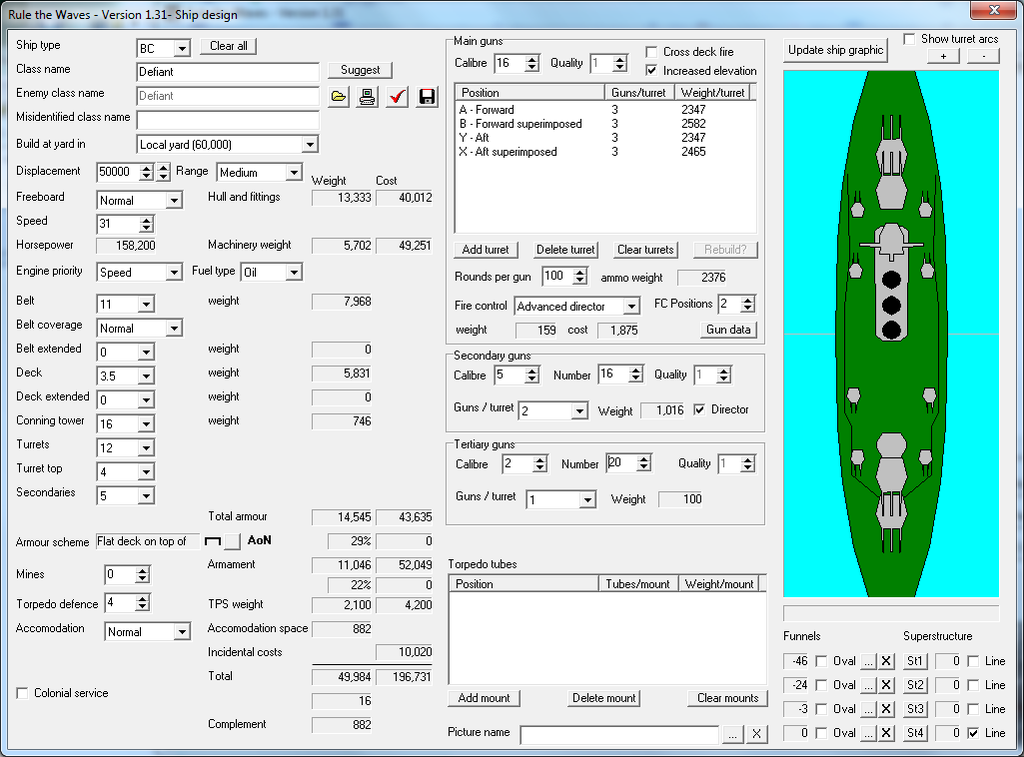

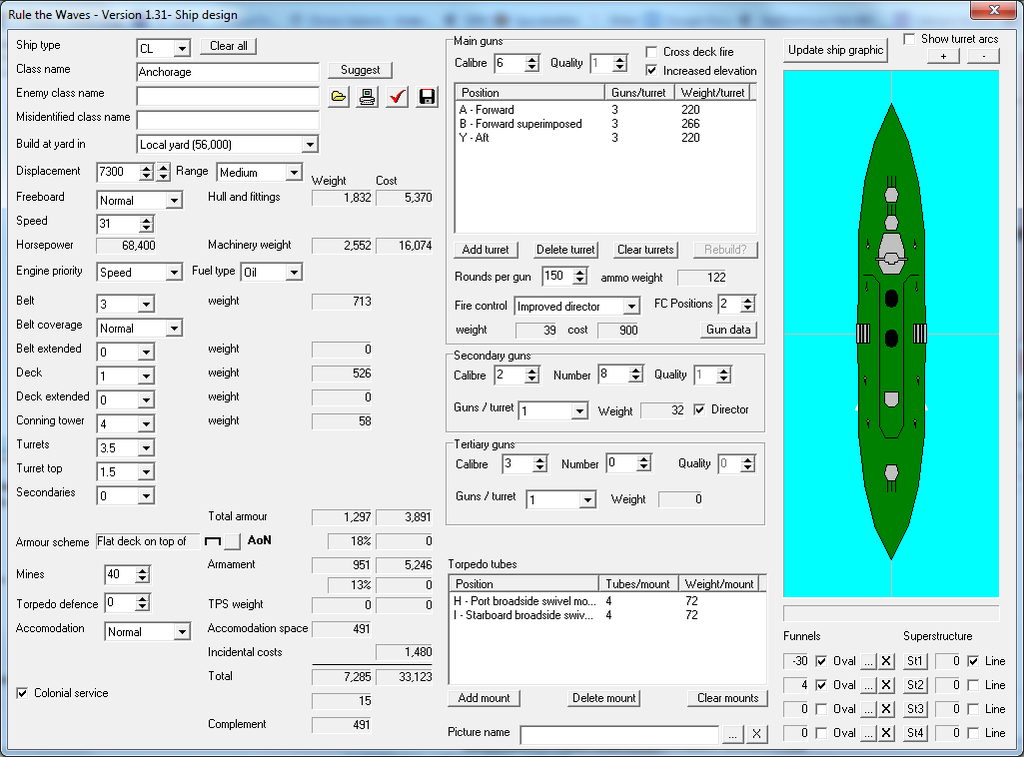

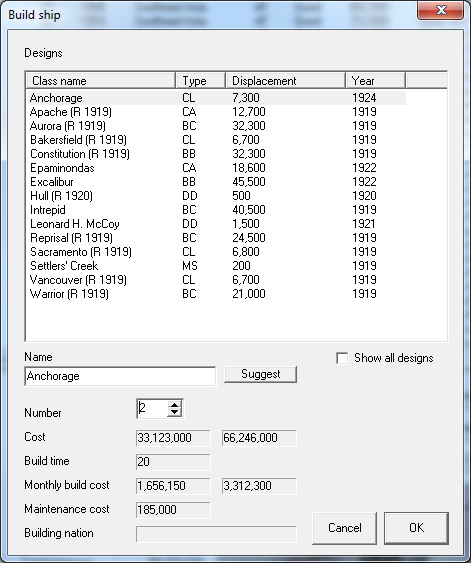

The Admiralty, with an eye on the future, decided to use some of the war budget to start building a new class of scout cruisers. This would be the first scout cruiser, or "light cruiser", to use multi-gun turrets. In this case, the ship would have nine 6" guns in three triple turrets in the A-B-Y arrangement. Eight 2" deck guns and two quadruple torpedo mounts would round out the weaponry of the ship. Forty mines would also be included on her mine-laying racks. A 3" armor belt for protection and 31 knot maximum speed rounded out the 7,300T design, dubbed the Anchorage-class in honor of the protected cruiser CRS Anchorage.

The Anchorage was laid later in the month at Hunter's Point in San Francisco. The Portland was laid in the slipyard beside her. Moran Brothers received a contract for two extra minesweepers to help keep up the minesweeper force.

August 1924

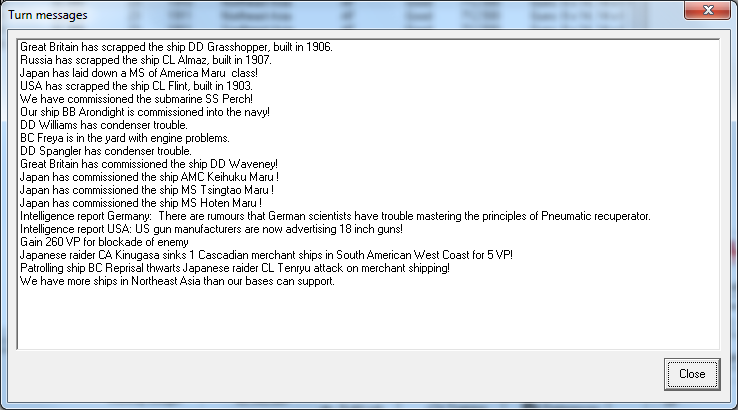

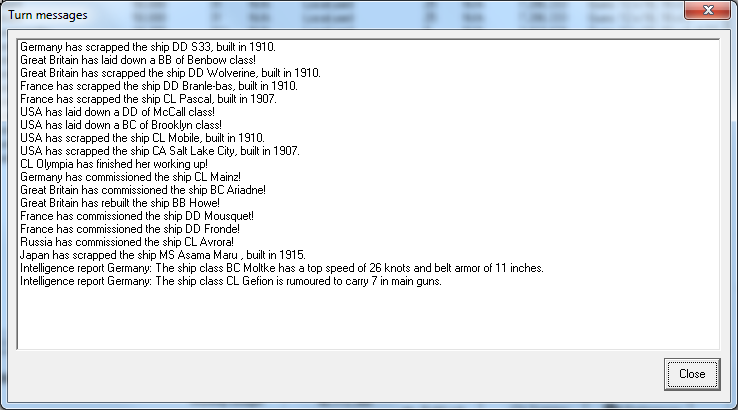

Gunnery experts completed new techniques to enable concentration firing, allowing multiple ships to engage a single target with better accuracy.

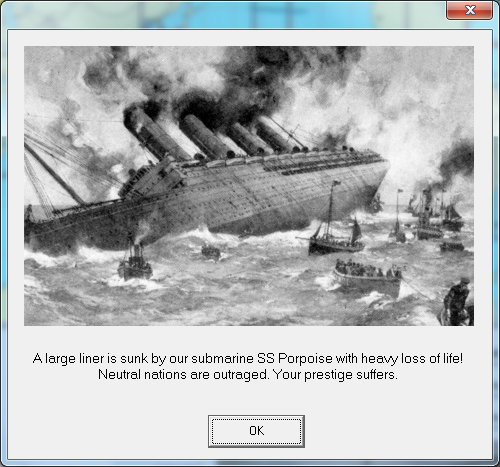

Cascadia's war effort took a black eye on the 5th of the month with the sinking of the Japanese flagged-liner Takasaga Maru, which had been returning to Japan from a trip to Europe. The Porpoise had engaged the ship in the twilight in the South China Sea - the light and the ship's structure had led Lieutenant Commander Jack Newton to believe she was a military transport, and he decided to use torpedoes instead of closing with his deck gun.

The torpedoes did their job too well; the Takasaga Maru's keel was blown in half and the ship sank rapidly. Only two hundred out of over a thousand passengers and crew got to the life boats or managed to get free before the ship went to the bottom - they included several dozen Europeans.

The attack outraged the European Powers. In Portland the Admiralty was also grossly displeased, as Newton had been skirting the rules of engagement. New orders were sent to the submersible force to be more circumspect when engaging any ship that could even potentially be a liner. Newton himself was recalled to a shore assignment. European leaders demanded his court-martial and declared the attack a war crime. Admiral Garrett considered it an exaggeration but bowed to pressure from Muniz and Naval Secretary Vargas in ordering a full JAG investigation.

The matter would resolve itself, eventually, in another manner: on the 29th of the month, Jack Newton shot himself in his lodgings near Manila Naval Headquarters. His suicide note absolved the crew of the Porpoise of the act and took full responsibility.

Aside from the Takasaga Maru, nine other Japanese ships were sent to the bottom by Cascadian subs, at the loss of one of their own.

But with their surface raiders on the prowl, the Japanese won the month. Kinugasa returned to her hunting grounds in the waters between Hawai'i and California, sinking four merchant ships during the month. The Kasagi sank 3, and the cruiser Otowa sank 1. Raiding out of Kaohsiung in Formosa, the Unebi caught a Filipino ship off Palawan and sank her as well.

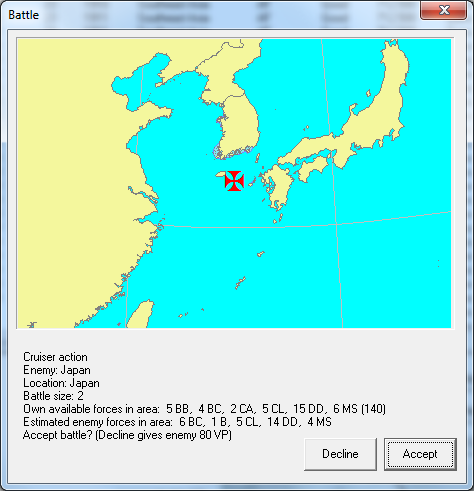

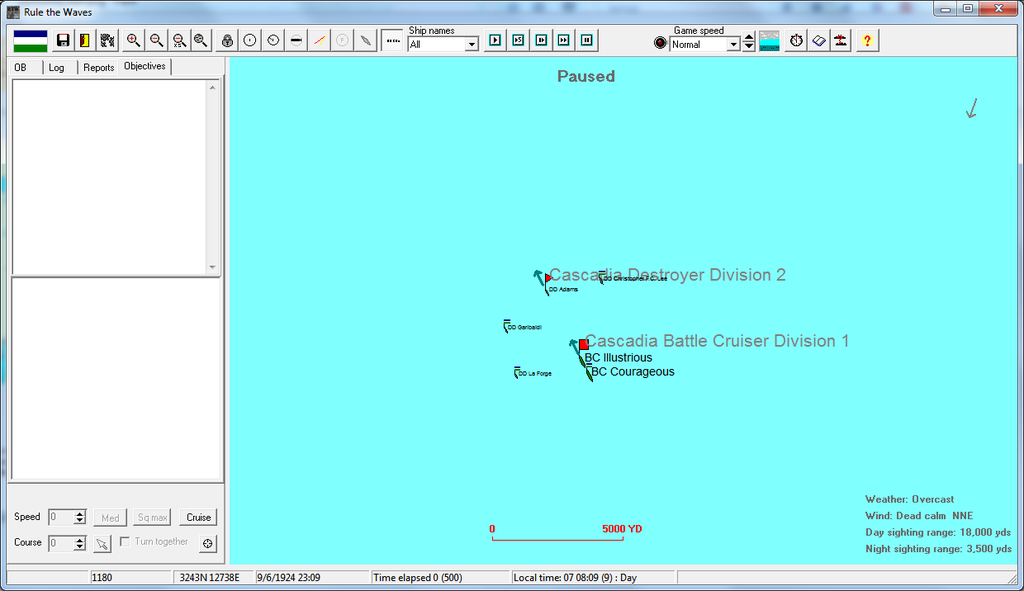

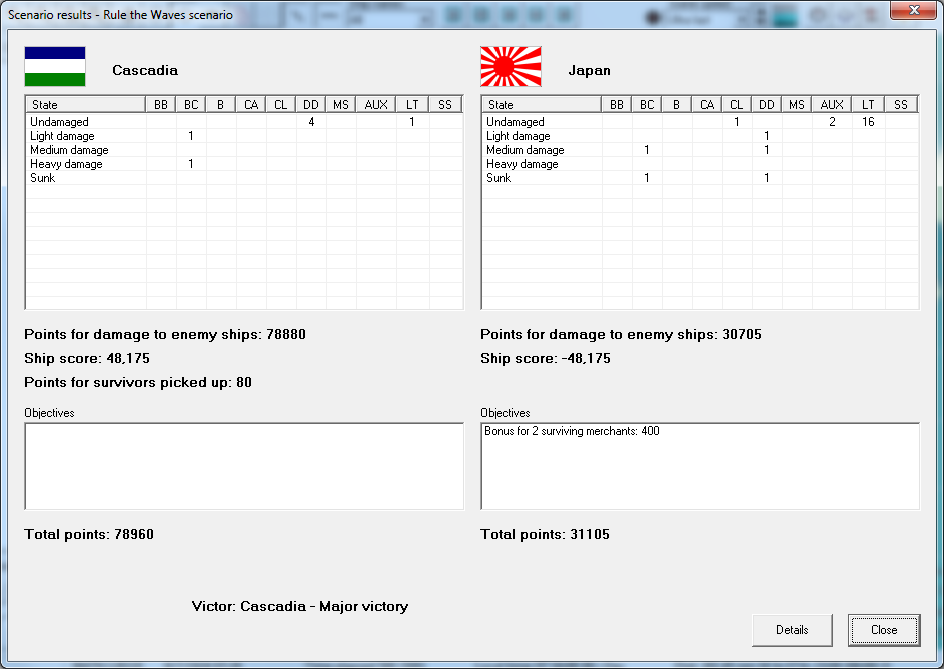

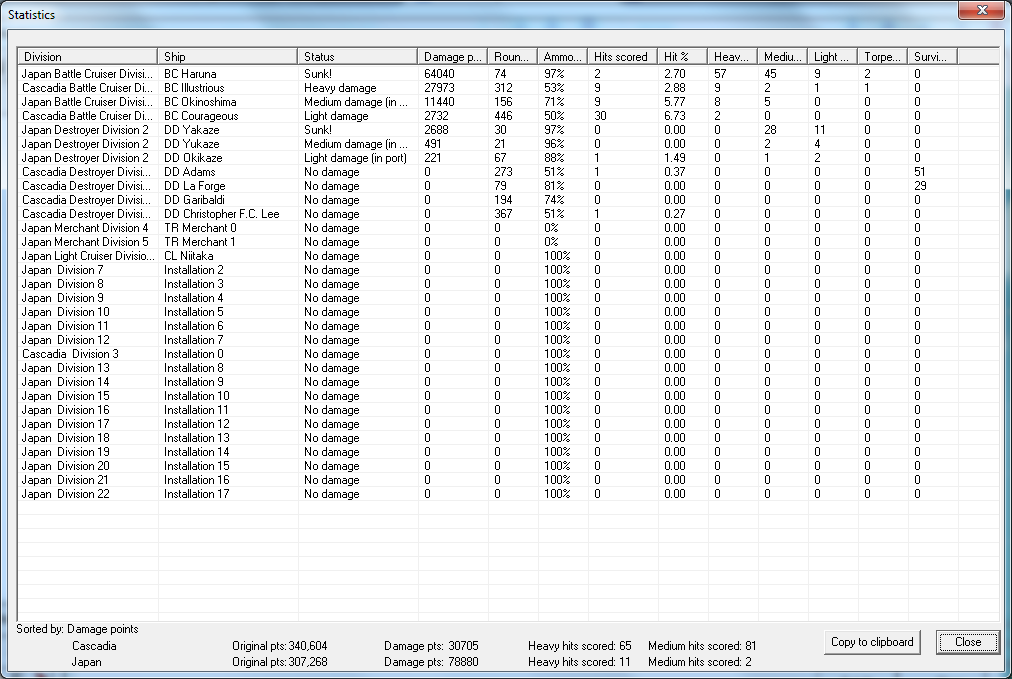

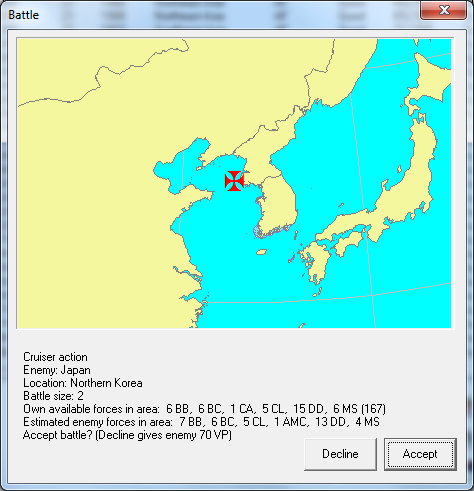

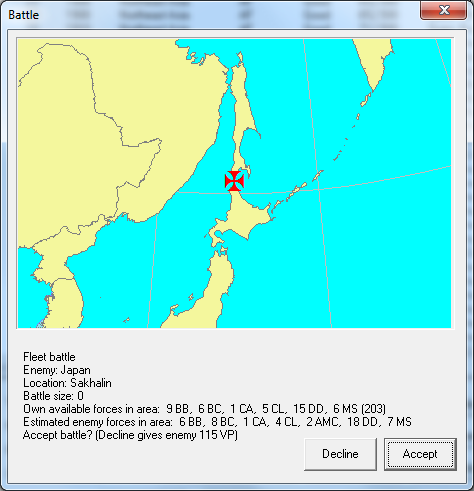

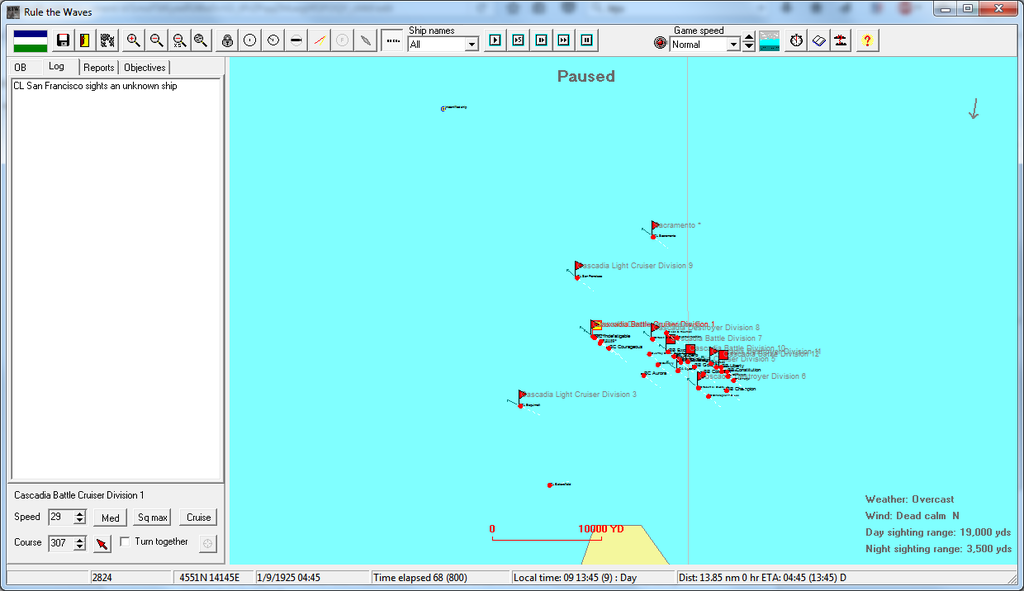

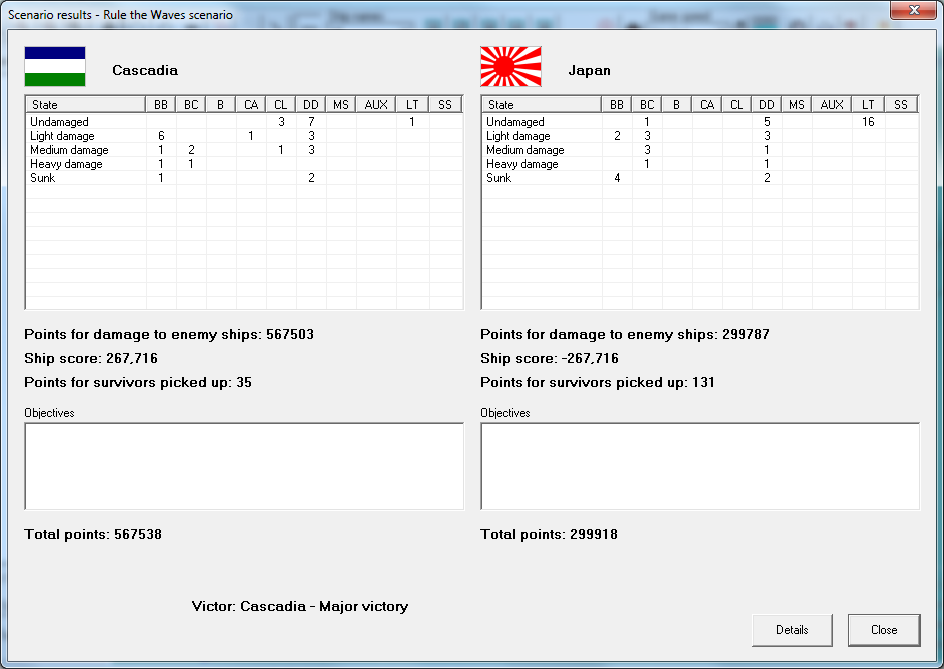

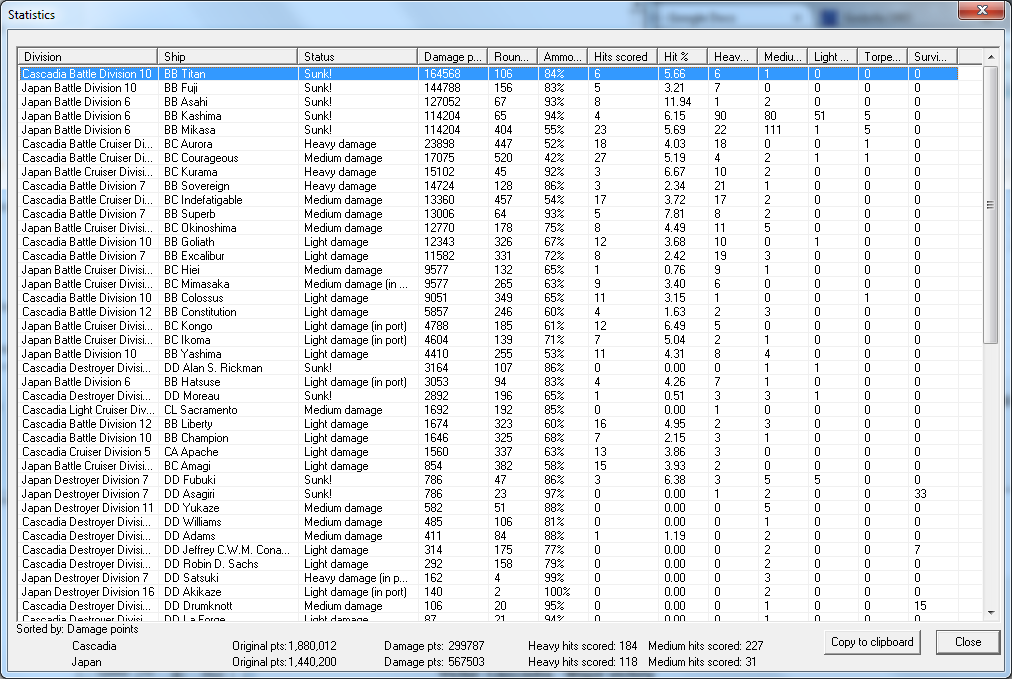

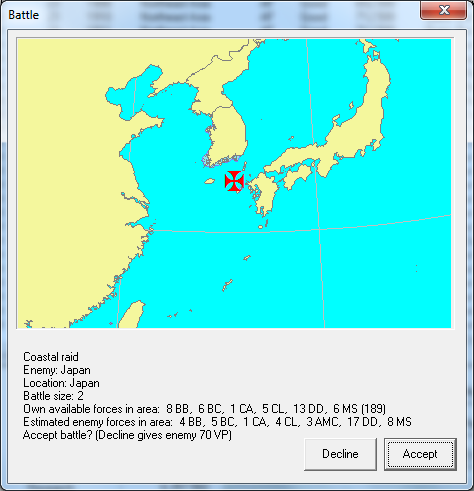

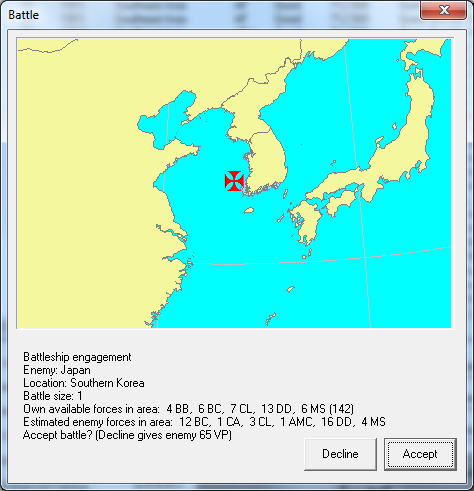

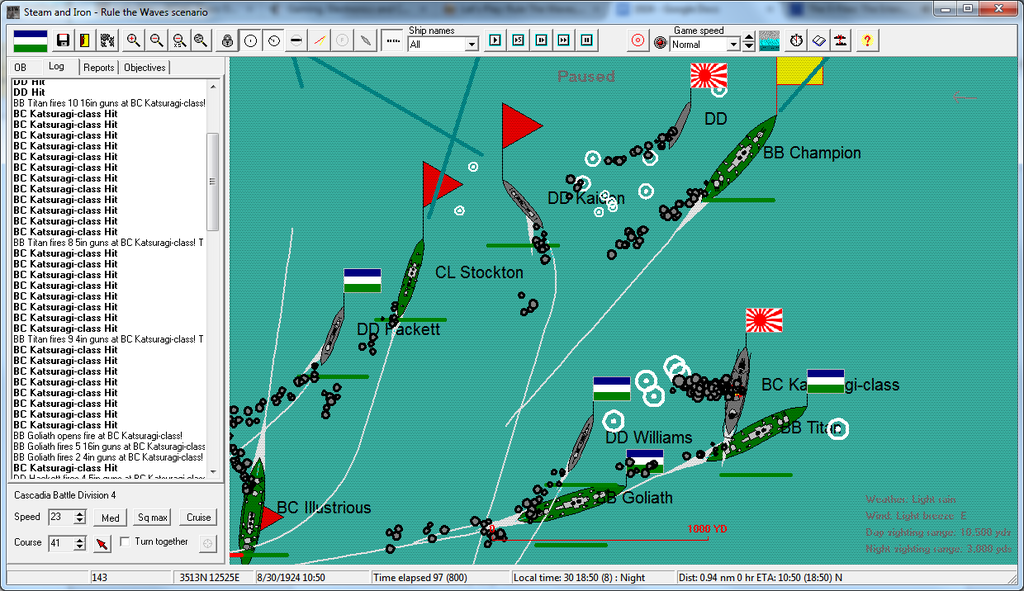

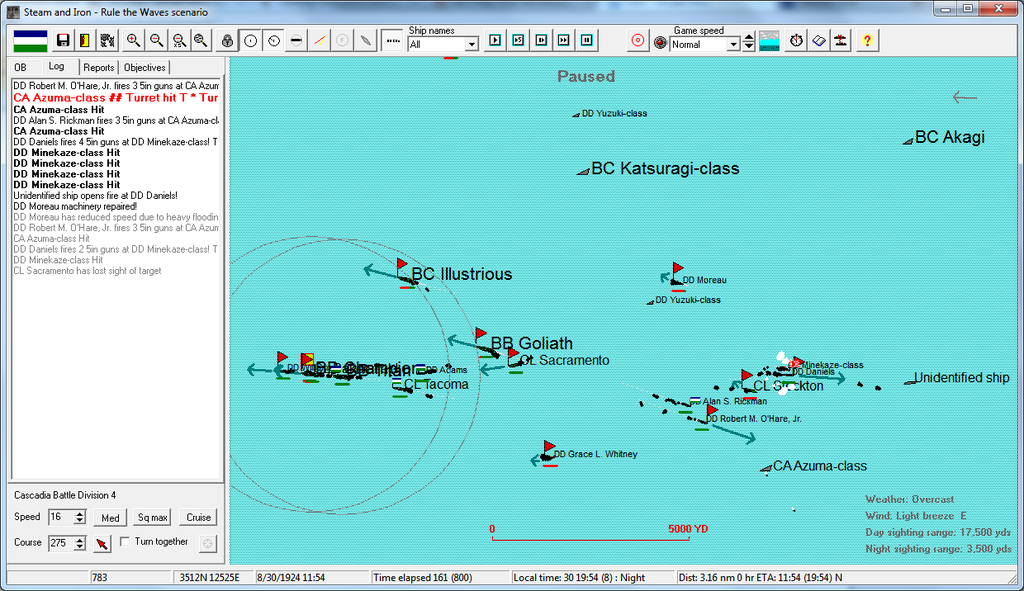

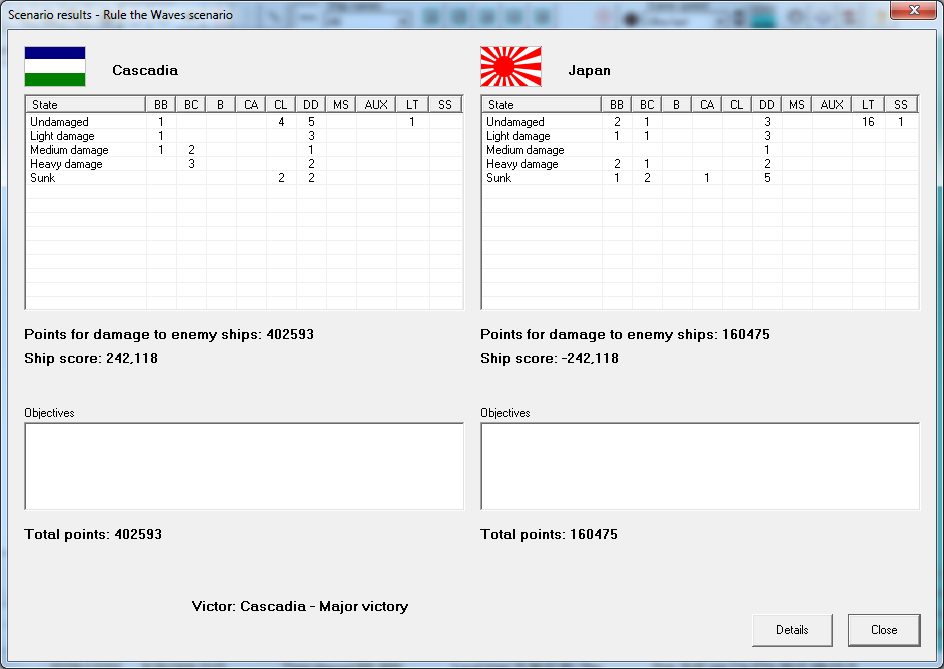

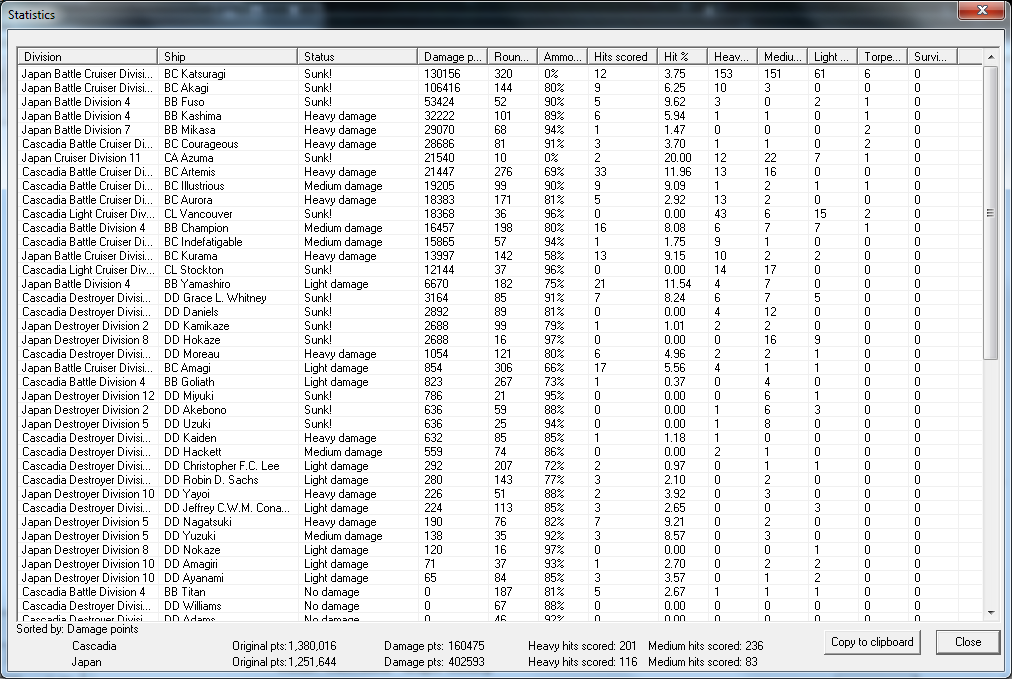

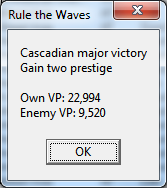

But everything else paled in comparison to what was to come at the end of the month. Late in the afternoon of August 30th, as a light rain drizzled over the Yellow Sea off the western coast of Korea, the Cascadian Battle Fleet went into action against the Japanese Navy in the first major naval battle of the war. Victory meant consolidation of Cascadian control in the Yellow Sea and open supply lines to Dalian and Port Arthur, defeat meant a Japanese vise that could strangle the defenders of the peninsula became a severe possibility.

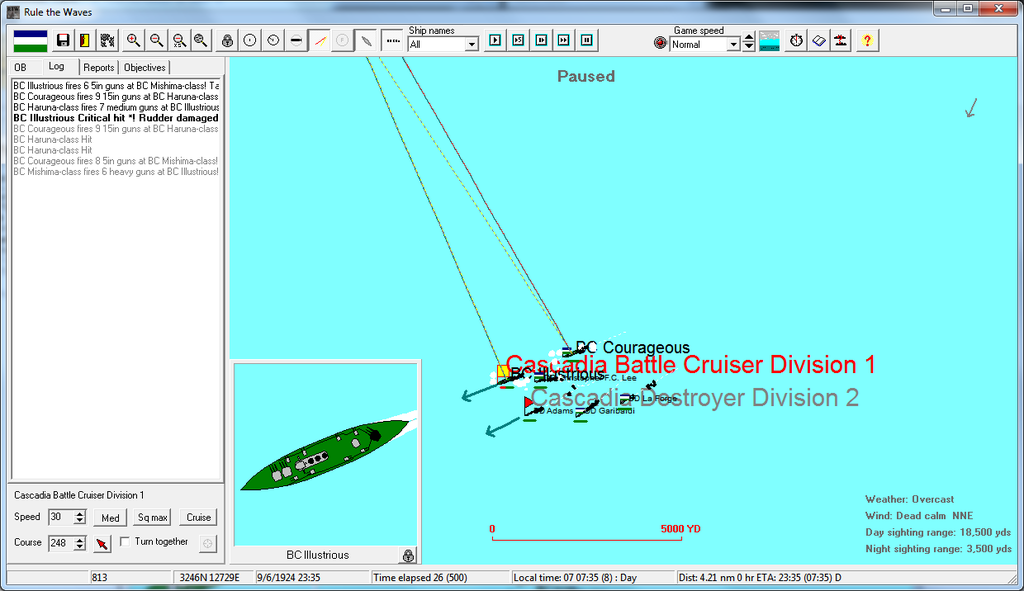

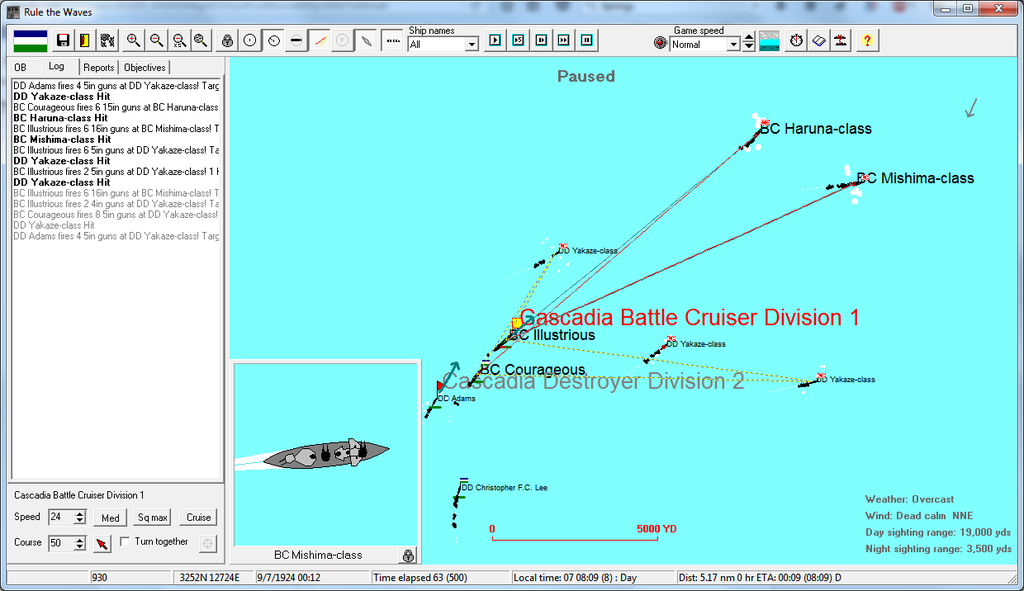

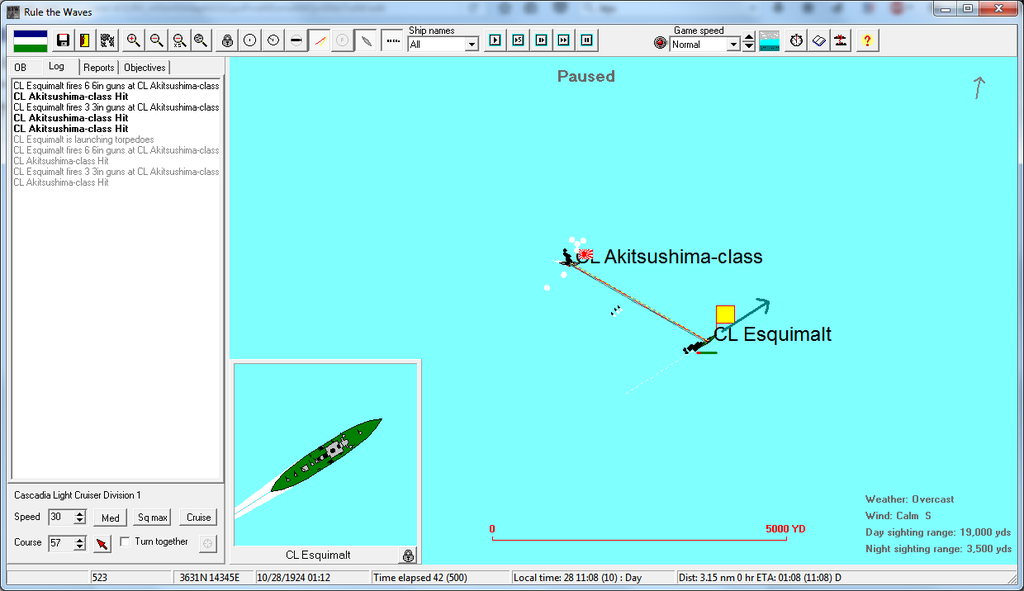

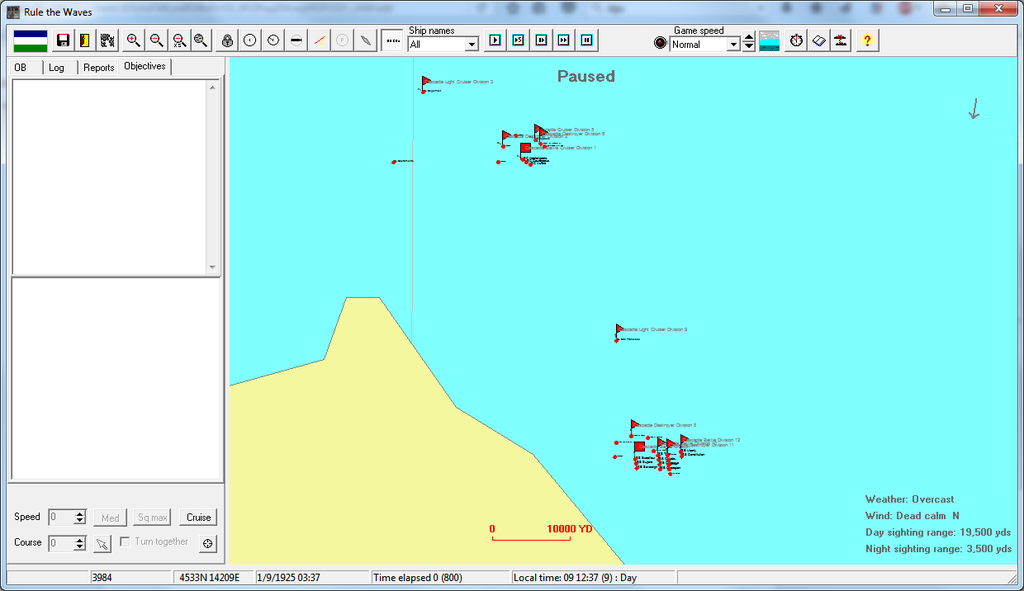

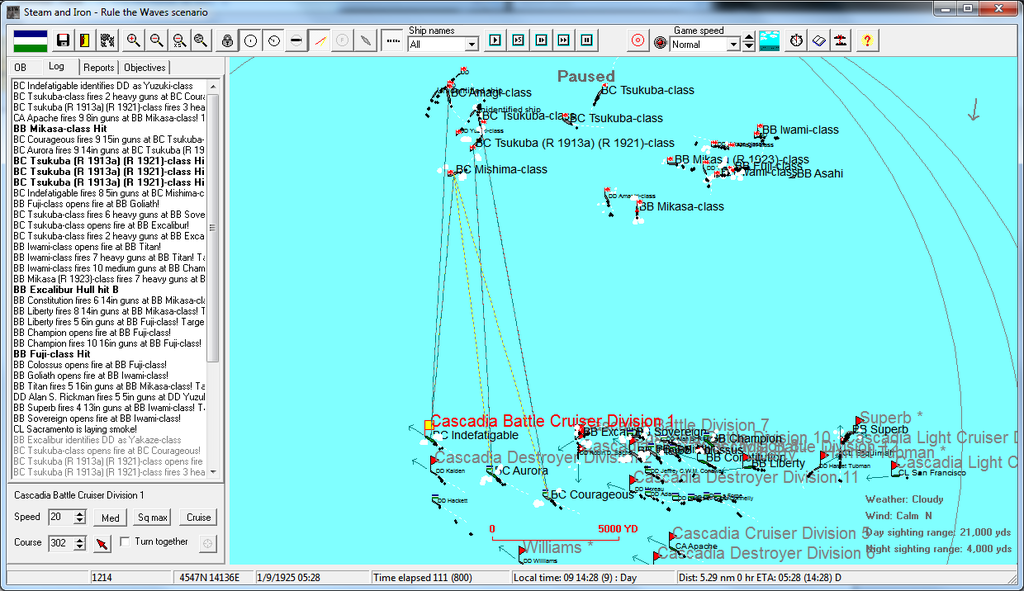

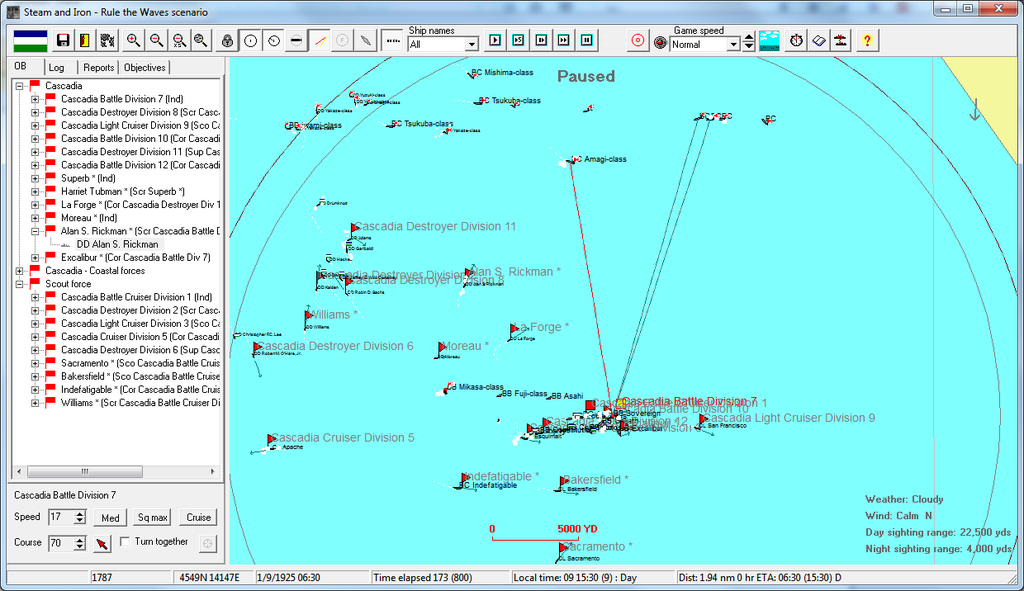

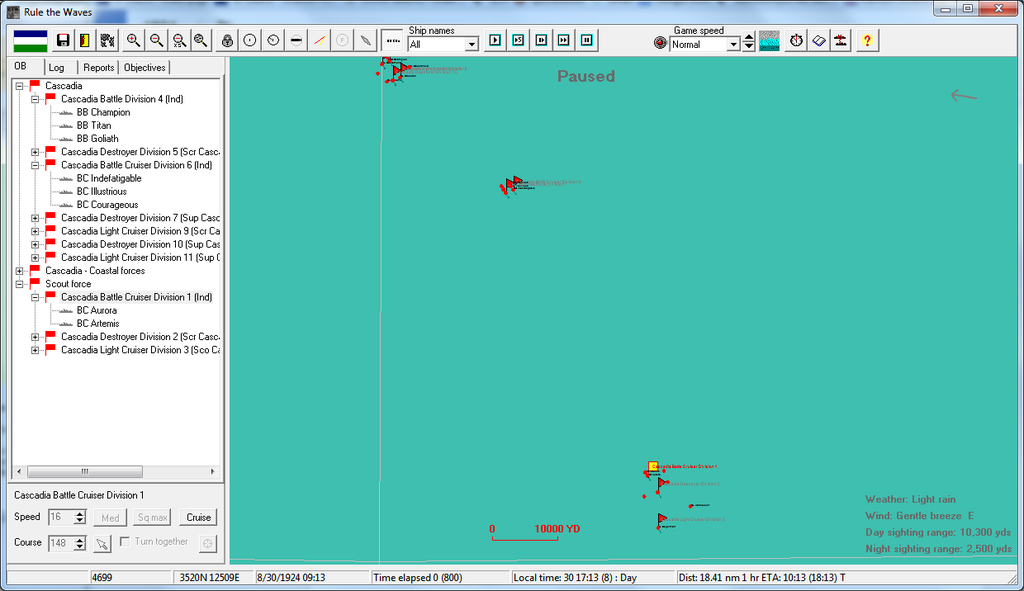

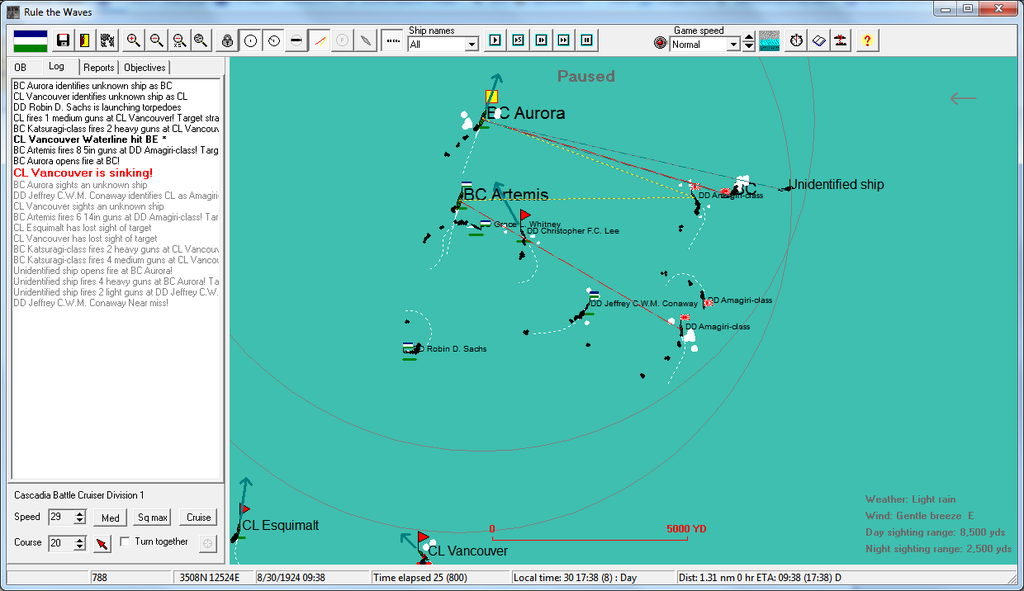

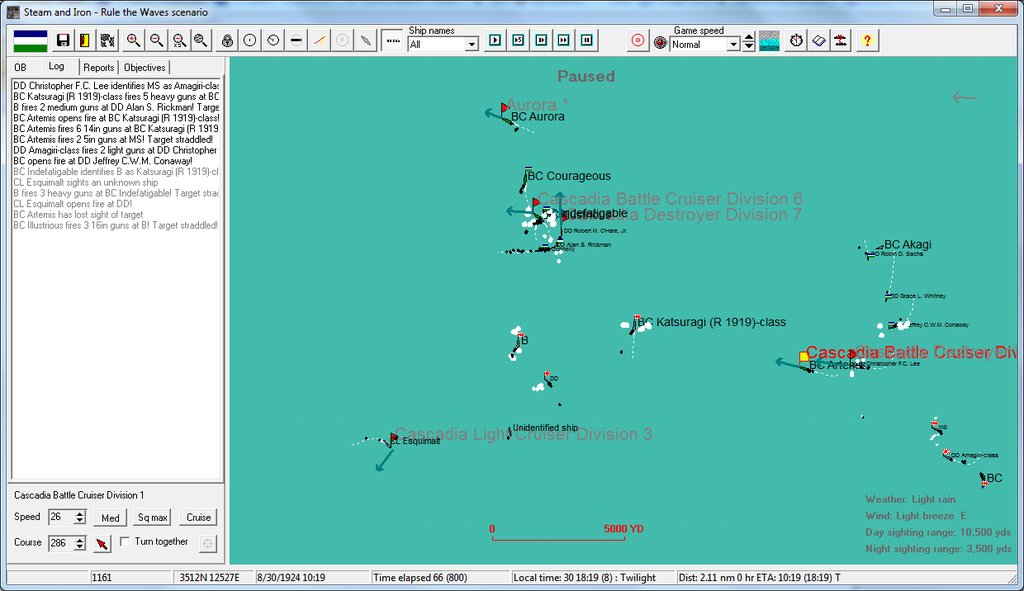

The Cascadian and Japanese fleets were out in force on the 30th. Admiral Phillip Wallace was commanding from the Titan - Champion and Goliath were with him, as were the battlecruisers Indefatigable, Illustrious, and Courageous, and all accompanied by a force of cruisers and destroyers. Miles ahead, the Scouting Force under Rear Admiral Jim Rawlings consisted of the Aurora and Artemis, with the cruisers Vancouver and Esquimalt and four McCoy-class destroyers

The Japanese force was more imbalanced, but heavy: a significant number of their capital ships were in engagement range: six sovereign battleships, five battlecruisers, and a modern-form armored cruiser. Fourteen destroyers were acting as screens, but significantly, no cruisers.

CRS Aurora

Eastern Yellow Sea

30 August 1924

Admiral Rawlings was a bear of a man and always had been. As a dark-eyed, dark-haired youth he had been the son of a fisherman out of Ilwaco, on the northern bank of the Columbia right inside of its mouth, and his size had been useful in hauling in the catches of the day.

He'd wanted more and had studied for it. After reading an account of the Battle of Mobile Bay in a book from Astoria, he had decided he was going to join the Navy and seek to become an officer. He'd narrowly passed the entrance exam for the Astoria Naval Officer's Academy at the age of 18, and with his parents' reluctant blessing had started his career there and was commissioned in 1897, just in time to be an Ensign on the armored cruiser Reliant during the Spanish War.

Now, 23 years later, he was an Admiral in command of the 2nd Battle Scout Squadron. His optics were at his eyes and his sight was directed toward the Korean coast. Miles behind was the main force of the Battle Fleet present at the moment, led by Admiral Wallace, and they were out seeking a fight with the Japanese fleet. So long as neither fleet had engaged, control of the Yellow Sea was in dispute.

Curse this rain, he thought. He couldn't see to the horizon, as even a light rain eventually obscured the distance.

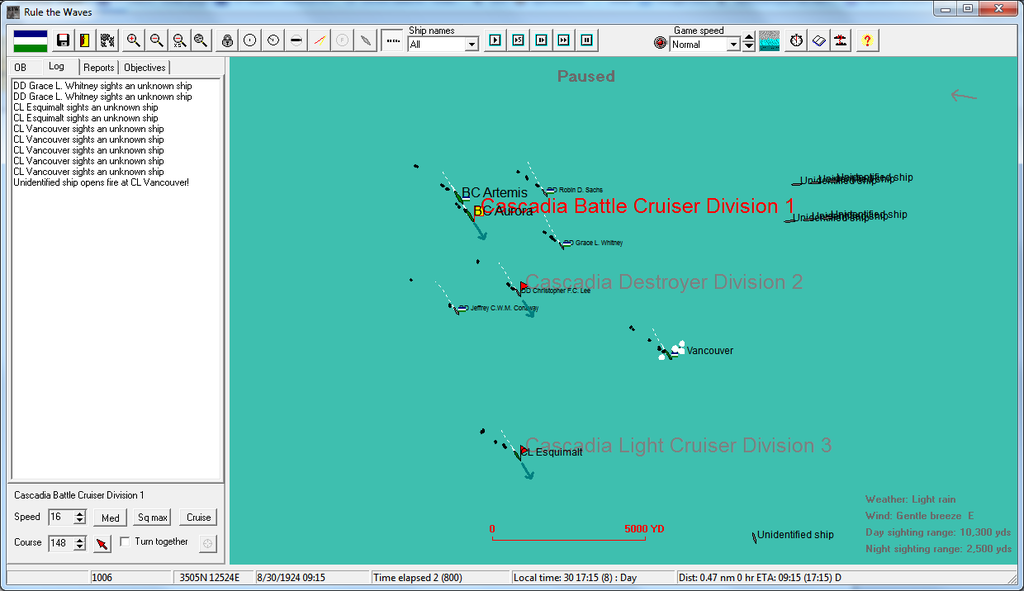

The local time clock showed 1715 when one of his officers made the report: their scout cruisers, Vancouver and Esquimalt, had spotted enemy contacts ahead.

Before he could give the order to change bearing, another report was already coming in from the destroyer Whitney: at least six more contacts to the east.

"Dammit." His scouting force was at risk of being enfiladed by the main and scout bodies of the Japanese fleet. "All ships, turn bearing 270!"

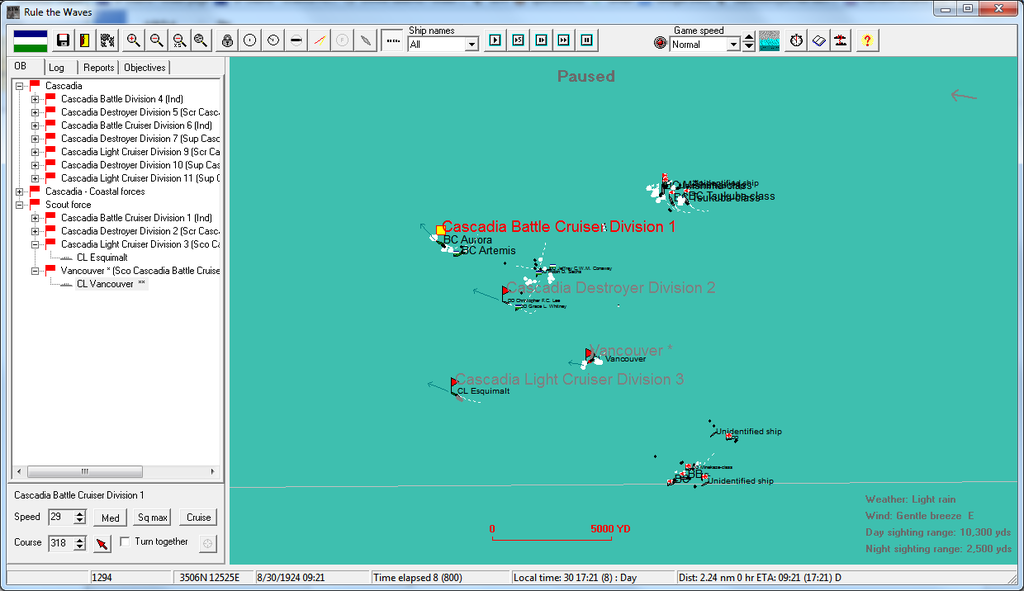

His eyes were back to his optics. Splashes rained down around several of his ships, joined by the explosions of hits. Vancouver was suffering the most during this opening bombardment. The scout cruiser had the full attention of several enemy ships - it was unlikely she would survive.

At Rawling's order, his ships shifted to be more northeasterly. He was racing to reunite with the main body of the fleet and, hopefully, to keep the enemy to the south from getting accurate fire on his ships. The reduced visibility from the rain was an asset here that could mean the survival of his force.

There was still the foes from the east, however. Destroyers and at least one enemy battlecruiser were coming up on his side. He was in a superior tactical position crossing their T, at least, even if the visibility issues undermined that typically-crucial advantage.

"Wireless from Vancouver, sir," came the voice of one of his officers, Lieutenant Peter Thompkins. "'We are sinking, abandoning ship.'"

Rawlings acknowledged with a nod.

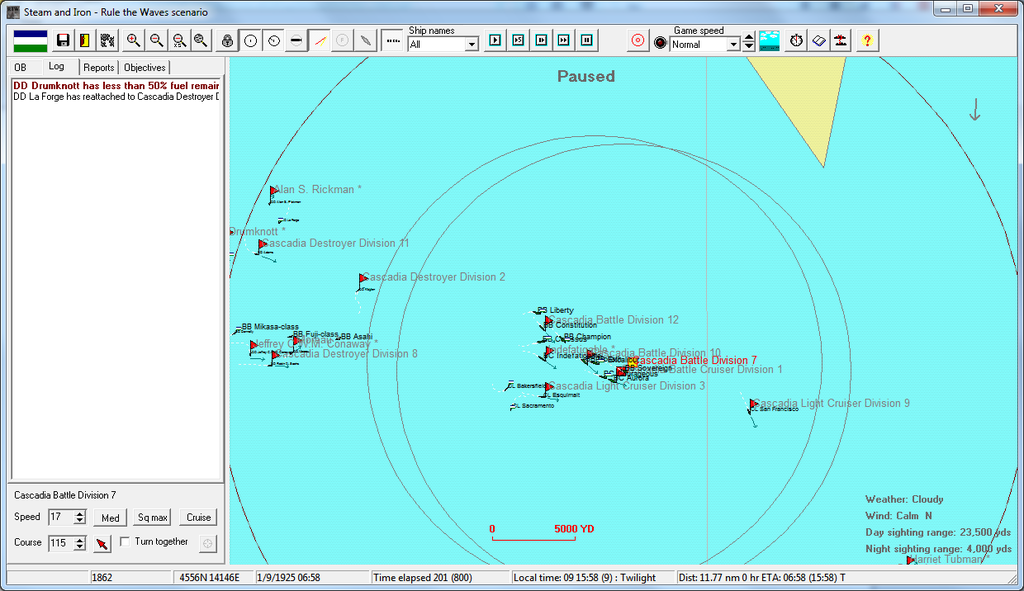

As the battle ticked closer to 1800 and the onset of twilight, the exchange of fire continued and made its murderous effect upon his ships. The Aurora endured repeated hits to her hull and waterline. Rawlings' ship shook and vibrated beneath him at the enemy's punishment.

"Sir, Captain Rockland's ordering a northwesterly course," said Thompkins. "He says we have critical damage and the ship must break off."

Rawlings took a moment to growl an assent. He wouldn't be able to transfer his flag to the Artemis at this rate - it would be left to Captain Smith on that ship to continue commanding the unit.

My first great battle at this rank… and I'm going to be sitting it out.

CRS Artemis

"Signal from Aurora, sir," reported Lieutenant Joshua Harper. "Admiral Rawlings has given you command."

For Captain Donald Smith, this meant a heavy burden. He was already commanding his ship - having to deal with the entire scout force was too much. "Commander Dunning, I'm going to the flag bridge. The ship is yours."

"Aye sir."

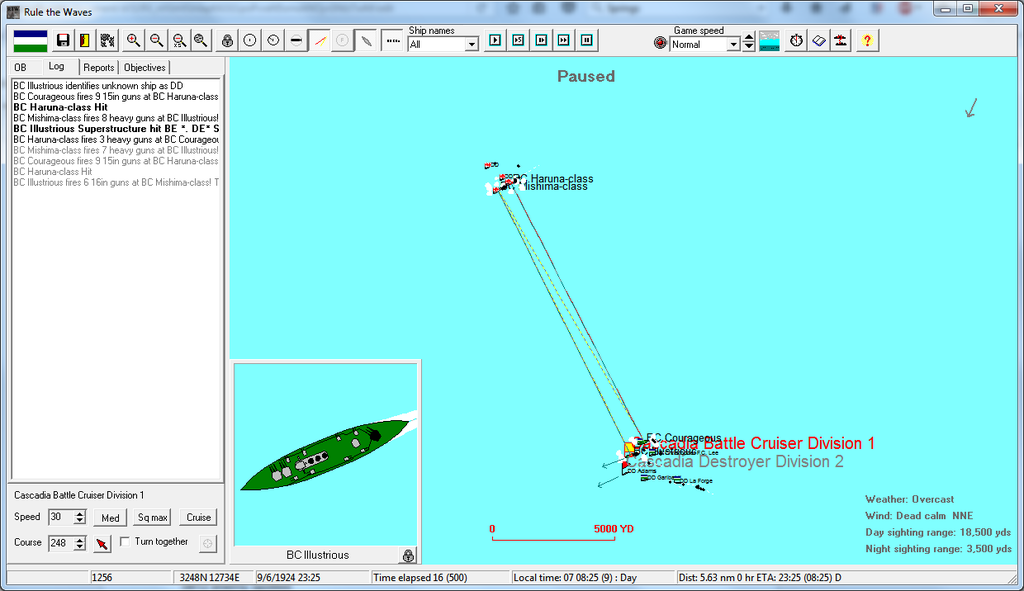

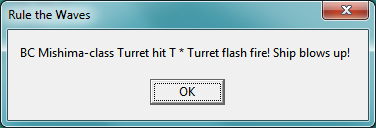

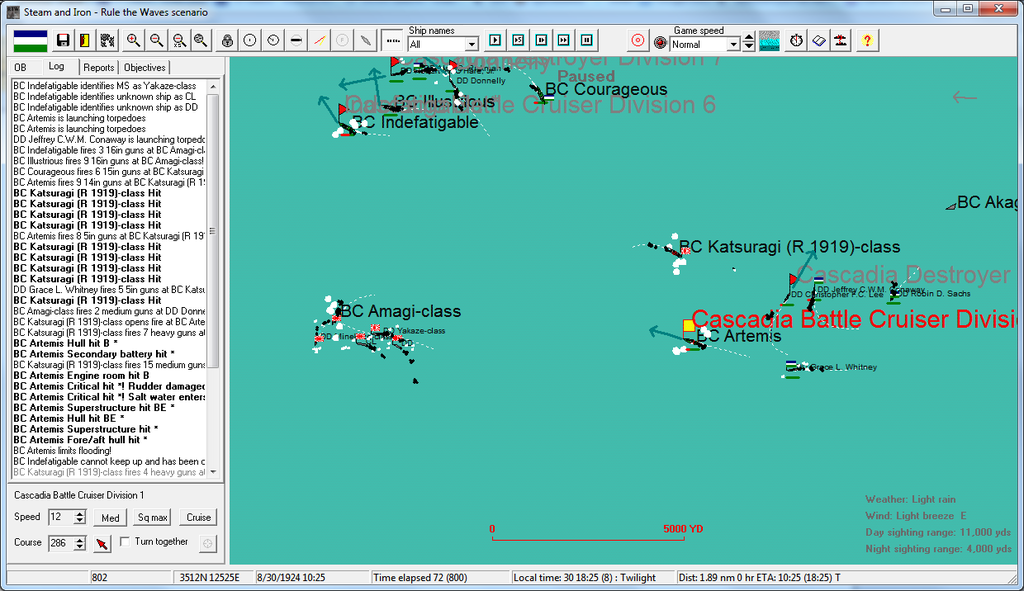

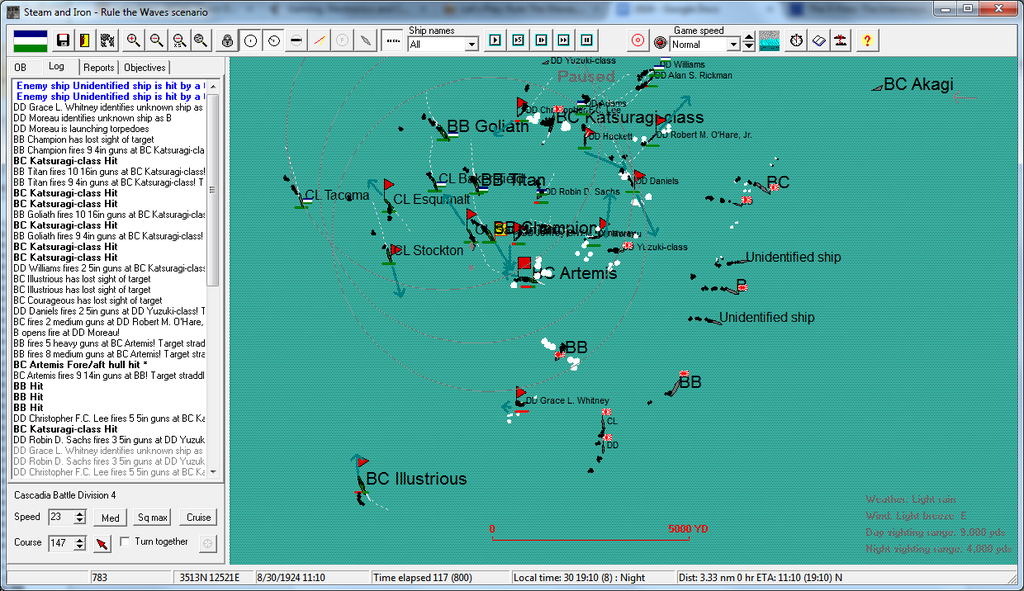

Smith left the command bridge and clambered his way up the ship's stairs and walkways until he found the currently un-used flag bridge. A group of officers joined him and took up positions to support him in his impromptu command. His eyes went back to the east. The enemy battlecruiser and Artemis exchanged another salvo. "Looks like a Mishima," he ventured. "Make our course more easterly as is necessary. We'll screen the Aurora as she gets away."

Through the gray rains the guns thundered and roared, each sending a ton of metal through the air that would maim flesh and steel alike if it hit.

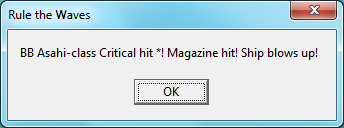

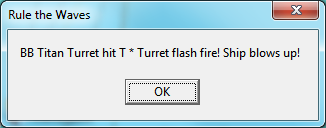

And sometimes, even more, as shown by the fireball that erupted just before 1800.

The enemy Mishima-class battlecruiser went up from a flash fire, the dreaded fate that could claim the most pristine vessel in an action.

"Commander Huerta on the Sachs is moving in to search for any survivors."

"Good man. Send to squadron, turn toward bearing 180 and on to 270. I want to sweep for their escorts as we start to go back to the west."

Artemis began to execute the turn. Meanwhile, to her east, the Battle Fleet began to arrive below the setting sun.

CRS Titan

Admiral Wallace was listening quietly to the reports on a battle he had no visual sight of. His mind made the calculation that the entire loss of an enemy battlecruiser had made up for the loss of Vancouver and damage to the Aurora. It occurred to him that Admiral MacCallister would have withdrawn at this point - the weather and the imminent twilight made a battle dangerous.

But I am not MacCallister. We have a chance here.

He decided to roll the dice. The Cascadian fleet continued to steam toward the action. For Wallace, he hoped to fall upon a division of the enemy fleet before nightfall. If this proved impossible, indeed, if the enemy seemed to do the same to him… then the same nightfall would prove a boon to a withdrawal. Cascadian ships had always been built with an emphasis on speed for this very reason: to dictate the engagement.

It was an advantage he intended to make use of.

"1st Battle Scout Squadron reporting they are coming in range, sir. Orders?"

"Maintain course. Find and target the foe," he replied succinctly. With that order he committed the Indefatigable, Illustrious, and Courageous to the fight alongside Artemis. As night fell, Titan and her sisters would join that fray.

And for his last order… "Order the signal given, lads. You know the one."

And indeed they did. The order went out to the signalmen, and the signal was raised for the entire Battle Fleet to see.

"Remember the Warrior."

CRS Artemis

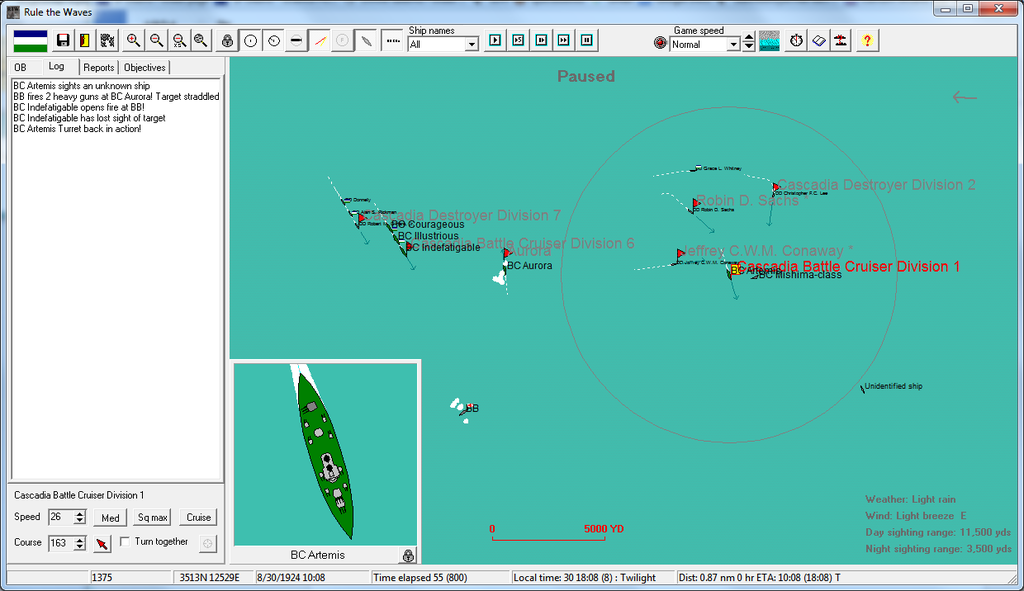

Smith saw the ships loom in out of the darkening rain. More enemy vessels were approaching from his southeast, including a battlecruiser. He gave the order for a more westerly course while the Artemis began training her 14" guns to the southeast.

While hits rained down on them, a form appeared ahead. The enemy southern force was moving up and engaging the Battle Fleet's forward element. And one enemy ship, a Katsuragi, was moving to cut off Artemis from meeting them.

He sent the order to Commander Dunning to turn to starboard, keeping a course necessary to rejoin the fleet, while their full battery would engage the foe who was starting to come up on their starboard.

Artemis suffered the enemy fury, and she made the enemy suffer too. At this range, even with the darkening twilight, gunners' duty was made easier by proximity.

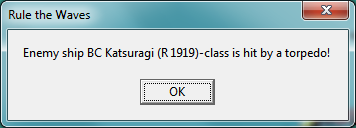

A plume of water erupted beside the enemy ship, courtesy of a torpedo fired by an escort. But the enemy's main and secondary guns were still blasting away, the Katsuragi as determined to sink them as they were determined to sink her. "Rudder control down, sir," came the report - they were trapped on the course for the time being.

There was a sudden blast that threw everyone off their feet. Glass cracked and broke at the front of the bridge. Smith crawled back to his feet and made perfunctory request for information.

But he already knew. An enemy shell had hit the bridge. The bridge he had vacated not half an hour before.

For a moment the prospect of his mortality was overpowering. But just a moment. He slammed the thoughts down and calculated instead the needs of his ship. The Artemis needed direction, and with the command bridge destroyed, it was left to him.

CRS Titan

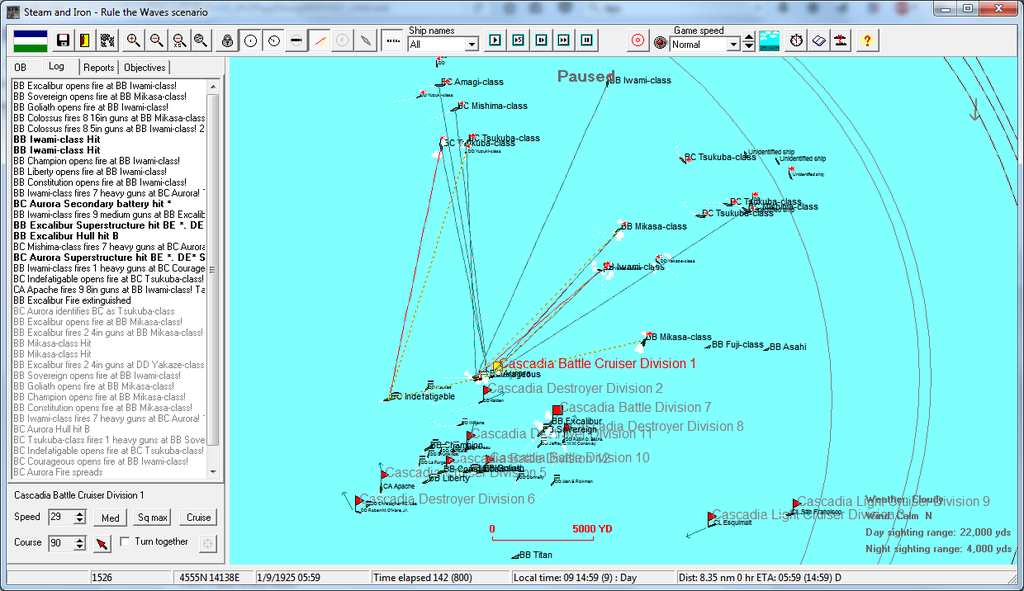

Night was already falling. And Wallace still had time to turn back.

He didn't.

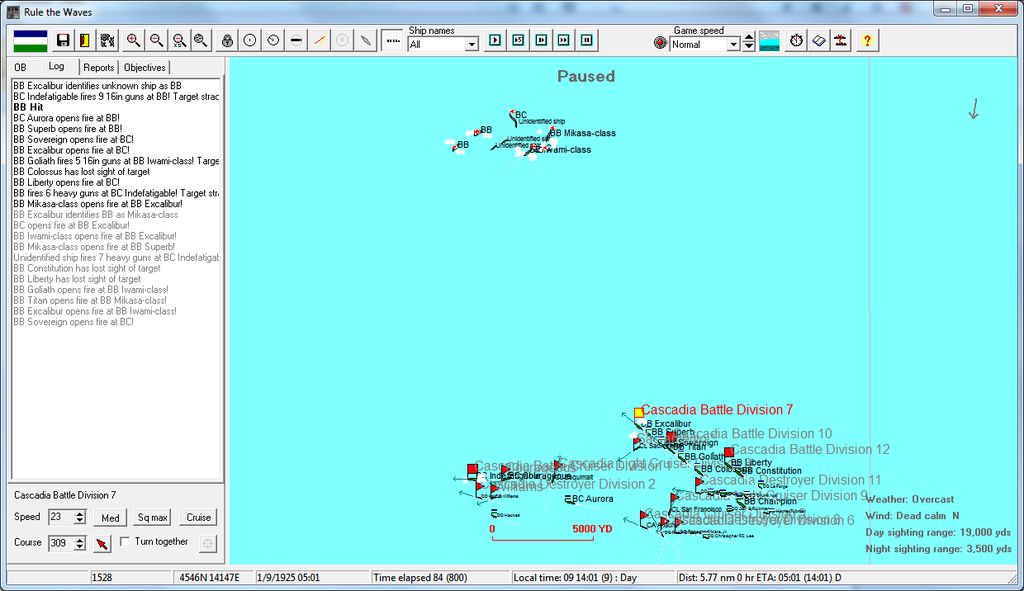

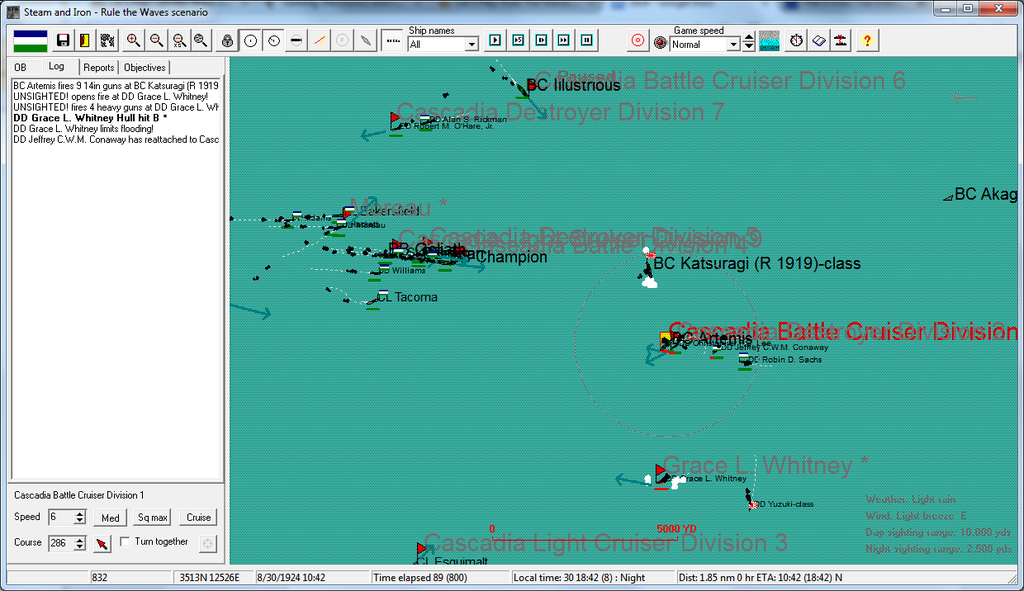

His ships charged forth toward the night, guns at the ready. Reports via wireless indicated the enemy fleet was to his east and southeast. He intended to fall on them, inflict maximum damage, and then break off and determine his next move.

An enemy battlecruiser appeared out of the loom. Some of her lights were still running - spotlights from his ships, especially Champion in the lead of the division, illuminated her further. Gunfire began to savage the enemy ship as they drew closer and she slowed.

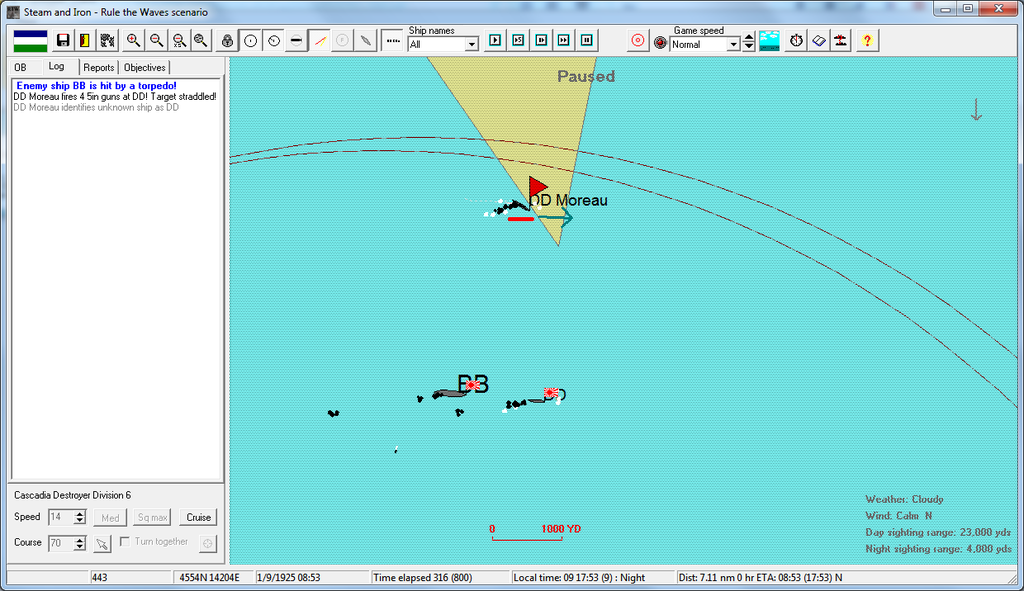

Around them the Battle Fleet was in a hot engagement. A report came in from one of the destroyers of a torpedo hit on an enemy Mikasa at 1837. Whitney's captain signaled his ship was going down less than ten minutes later - whether she had struck that blow or not, Wallace was uncertain. He was following the engagement as a whole. A mental picture formed in his mind of the enemy fleet, still generally split between its eastern portion and southern, and the Battle Fleet was a blade aimed straight at the eastern portion.

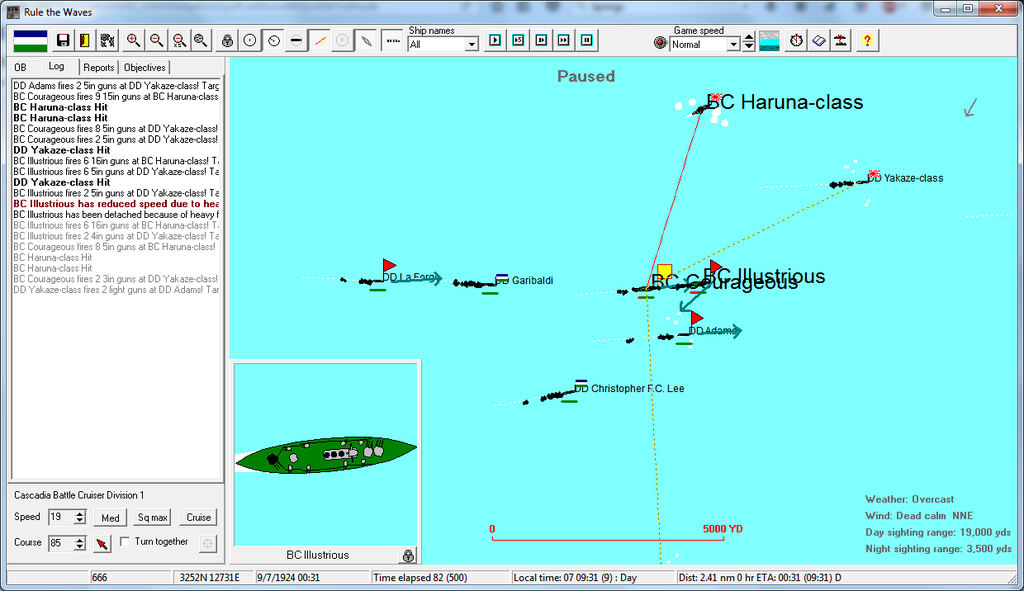

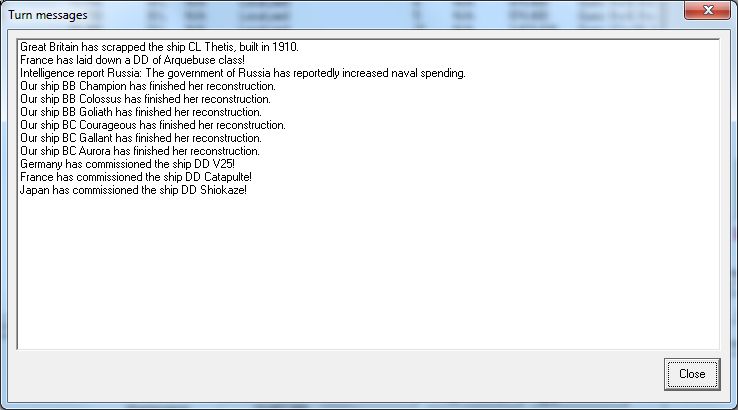

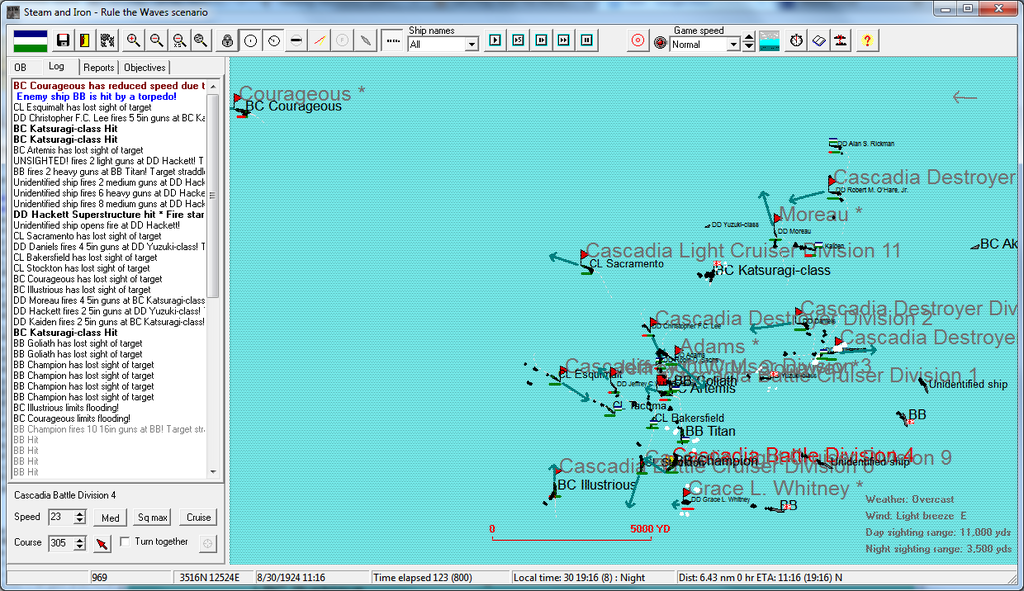

The enemy's destroyers were still a nuisance. They darted in and out of the dark - both Illustrious and Courageous took torpedoes from them, and both ships kept fighting.

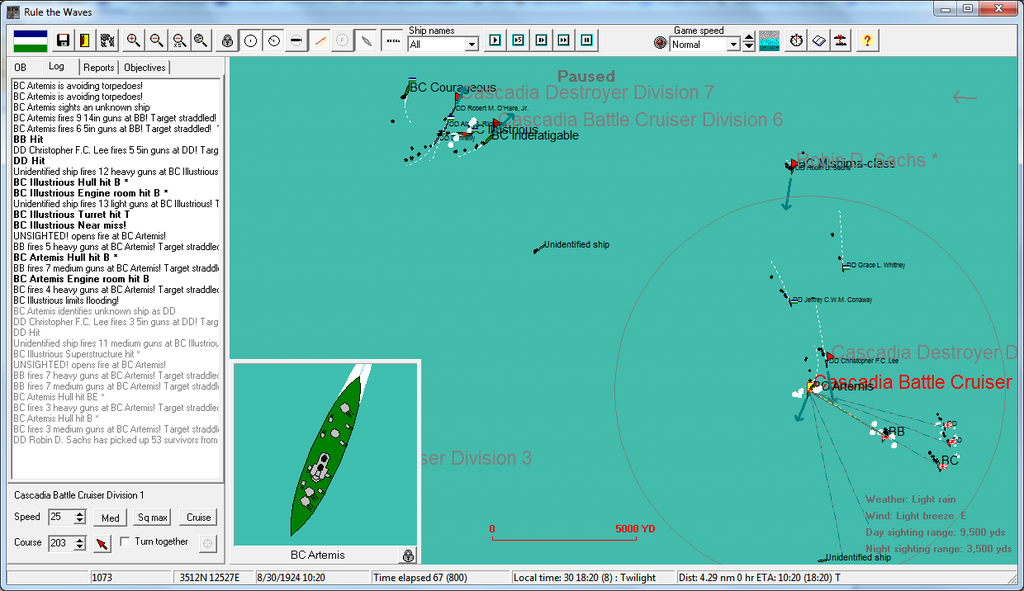

He looked up in time for the grand view at 1850.

Night seemed to turn to day for an instant as all of the Titan's port-side weapons erupted in fury. They were so close he could see the burning Katsuragi-class battlecruiser as the Titan's broadside slammed into her. Virtually every shell struck the enemy ship. It was a simply stupendous amount of firepower. Given the other hits she was taking, Wallace knew the Japanese ship was a casualty of the battle. It was time to direct his attention everywhere.

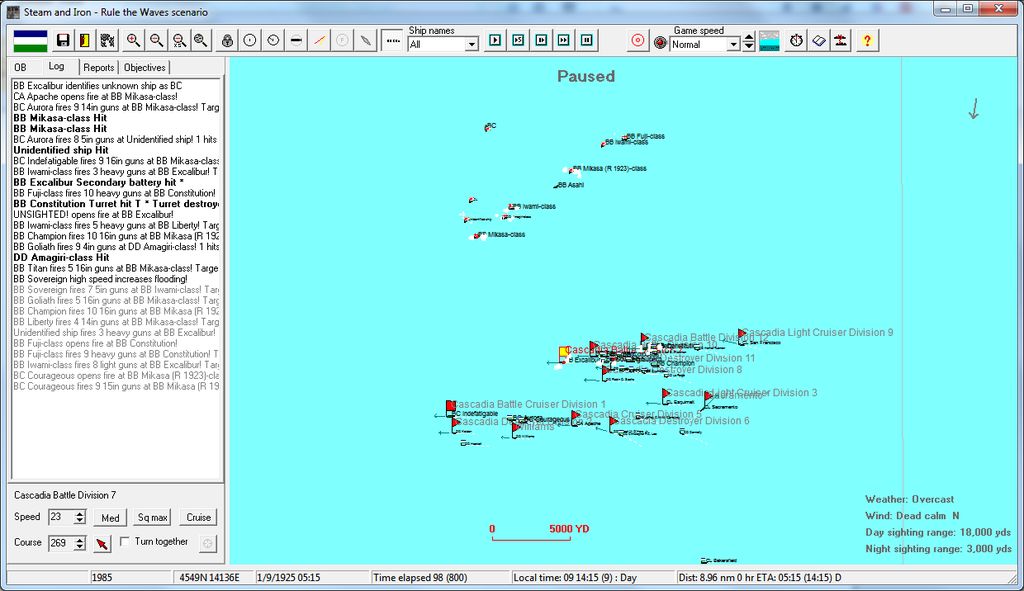

The fleet turned to the south-southeast, bearing 170, as wireless reports from the ships ahead of Titan indicated more foes.

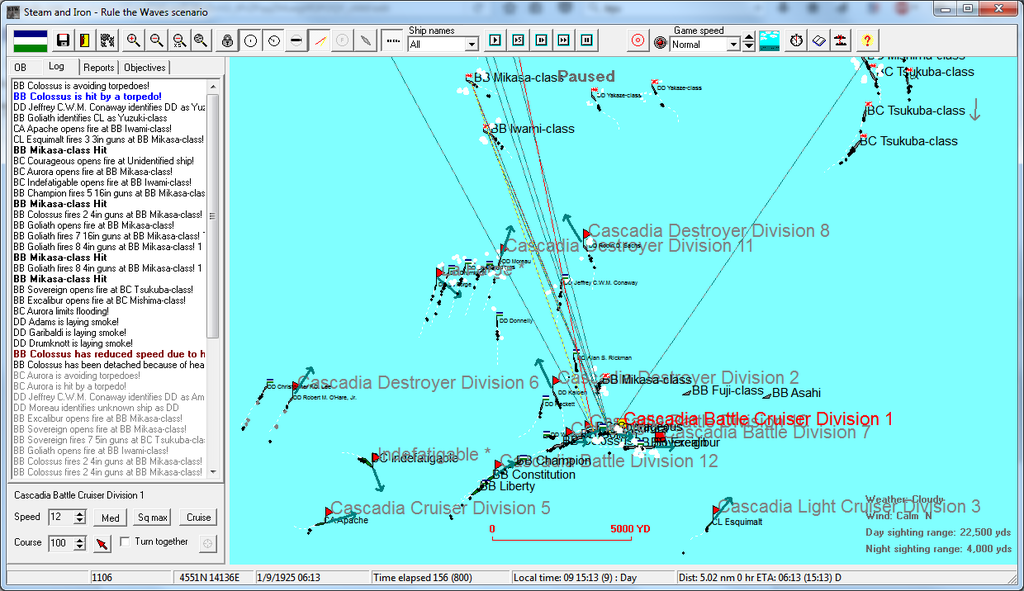

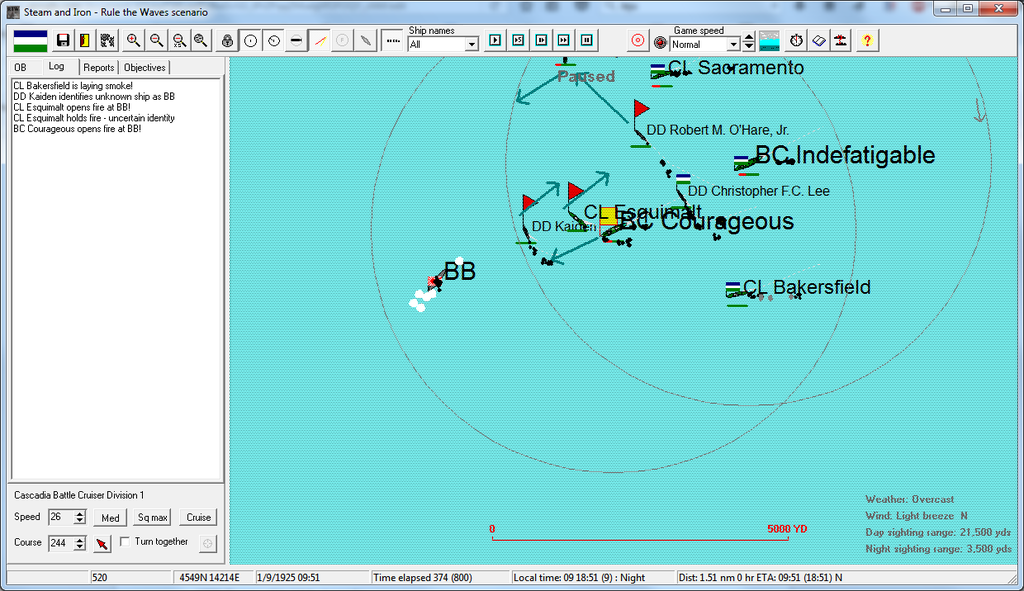

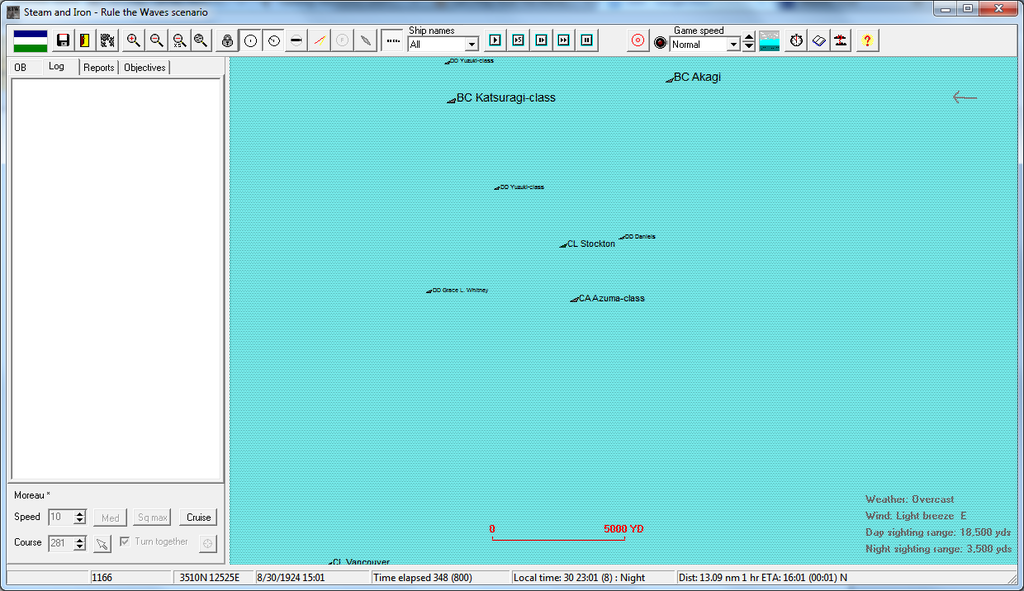

Searchlights and flames lit up the night; both fleets had to be only a few miles apart to have any chance at landing a hit on the other. Most of the enemy was now to the east more than the south. Fire was still exchanged; an enemy cruiser, too large to be a scout but not large enough to be a battlecruiser, took multiple heavy shells until she was dead in the water.

Wallace let the destroyers do the work here, and they did the work brilliantly. Several more torpedo hits were reported after 1900 hours.

Again the Cascadian admiral was left with a decision: did he risk his force by pushing toward the enemy for point-blank shots? The numbers he was hearing from those destroyers able to identify enemy vessels indicated he was outnumbered in capital ships. He had already sank at least two enemy capital ships - his own force wasn't untouched either, with three battlecruisers already limping back to Tsingtao.

By 1915, he made his decision. "Signal to all ships, make bearing 270 and break engagement," Wallace ordered. "We've done what we can tonight, lads."

His order, for the most part, put an end to the battle. Still, even as his capital vessels turned away, the destroyers continued to skirmish with foes behind them. The crippled Stockton took hits that finished her off, costing Wallace his second scout cruiser of the evening.

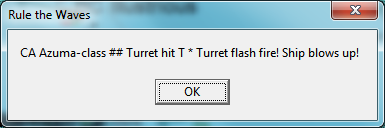

At 1954 a distant fireball spoke of another vessel blowing up - the report came that it was an enemy heavy cruiser, claimed by a shell from the O'Hare striking the battered turret of the ship and causing a flash fire.

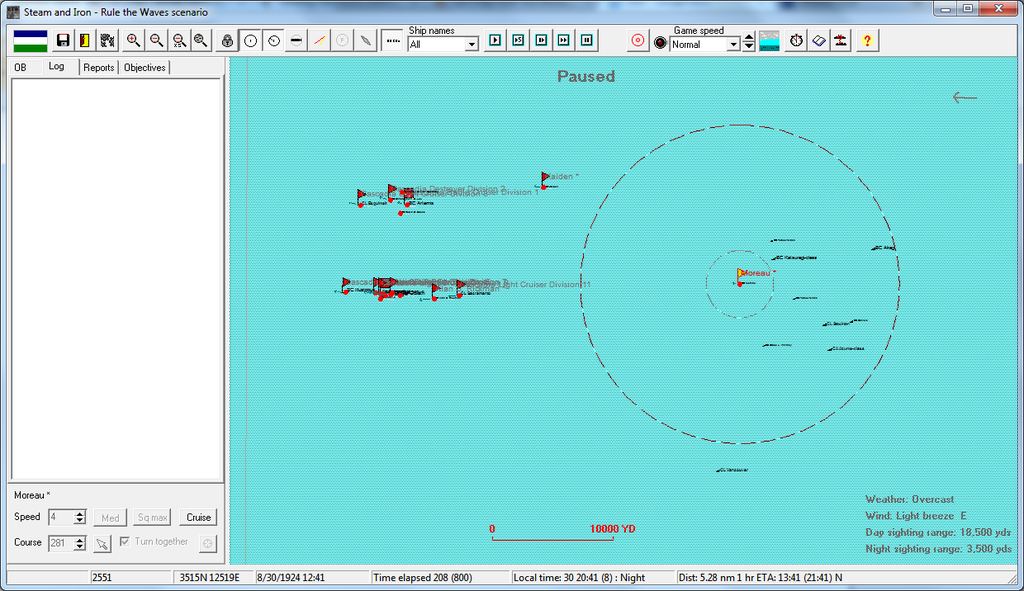

The fighting all but stopped at this point; the Japanese had disengaged as well, their ships moving for Korean ports for shelter. Admiral Wallace noted times in his logs as reports came in to confirm the condition of his surviving ships. Commander Green on the Moreau indicated his need for machinery repairs and that he had fallen behind.

Wallace ordered destroyers back to screen Green's ship. He would learn later that his orders had not been relayed properly and were thus not implemented for hours. It was not until the next morning that the O'Hare and Adams linked up with the Moreau as she limped back to Tsingtao. Appropriate measures would be taken to prevent a repetition.

As Wallace's bruised fleet steamed west for Tsingtao and its expanded repair yards, he contemplated the night's action. He had gambled, and gambled greatly, on the quality of his crew. That the gamble had apparently worked given the enemy losses… that had saved his job, certainly.

"A solid night's action, sir," remarked his aide, Commander Paul Lawrence.

"Yes," he remarked. "But we were lucky. Looking at these reports… the enemy had greater force than we did, Commander. If not for the rain and the night, they might have brought it to bear. The next time the Battle Fleet goes out… I intend to bring more force." Wallace looked out over the dark seas around his flagship. "The next time we meet the Japanese, I intend for the outcome to be truly decisive."

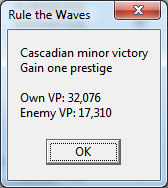

The Battle of the Yellow Sea had been the fiercest naval battle the world had seen in decades, in terms of sailors killed and ships damaged or sunk, and it would invite comment from across the world on the ferocity of the action.

Even before the news of the Battle of the Yellow Sea hit the newspapers, it was clear that public enthusiasm for the war had not waned. Anti-war agitation, socialist agitation, rightist… none of it worked for those favoring it. The country was socially unified behind President Muniz and Secretary of State Montelbano… and, to a great deal, behind Admiral Garrett as well.

Once news of the battle hit, another name joined their names in the accolades of the nation. Admiral Phillip Wallace was being hailed as the dashing naval commander the Republic had lacked in the wars with Germany. Reports from correspondents aboard the Titan and other ships about the bold night charge of the Battle Fleet and Wallace's success was a jolt to the populace. Proud parents named newborn sons "Phillip Wallace" (much as "Stephen Garrett" had been a popular name in the year after Manila Bay).

There were critical commentators. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer was leaked a letter from Roger MacCallister. The retired commander of the Battle Fleet had protested to Naval Secretary Vargas that Wallace had "unnecessarily jeopardized the fleet, and our war effort, with a reckless night engagement" and declared "Unless restrained by firm authority from the Admiralty, Wallace will cost us the war". MacCallister's grumbling was echoed in some halls of the Admiralty as reports of the damage to the fleet came in.

Admiral Garrett's response, in private, spoke of his own views of the matter. When a Captain in the Personnel Office remarked upon the losses incurred on the night of August 30th and how MacCallister had never cost the Navy such blood in a battle, the Admiral's retort was soon on the lips of every officer in the building: "In one night the Battle Fleet under Phil Wallace sank more enemy capital ships than Roger MacCallister's commands sank in his entire career."

Unrest at 0

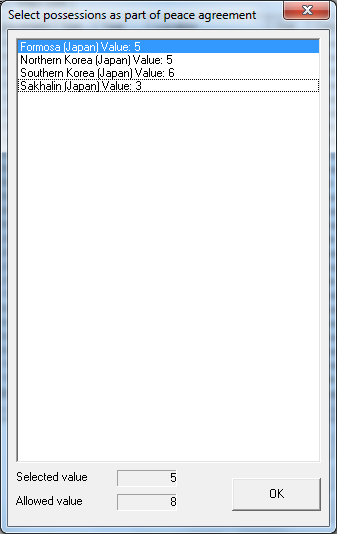

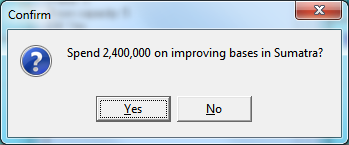

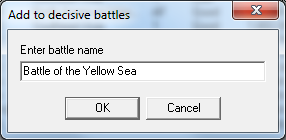

As news came in to Portland on the scope of the damage from the Battle of the Yellow Sea, Admiral Garrett directed ships to transfer from Manila and the Marianas to Tsingtao and Liaotung. This would undermine proposals to invade Formosa with troops, but the Admiral judged the need to hold the sealanes to China, and the prospect of a blockade of Japan, to be more important.

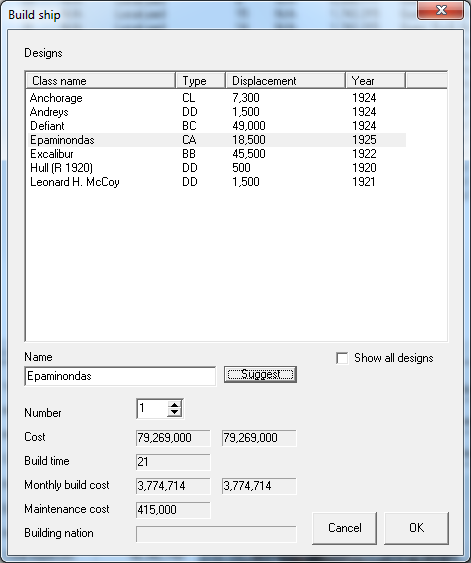

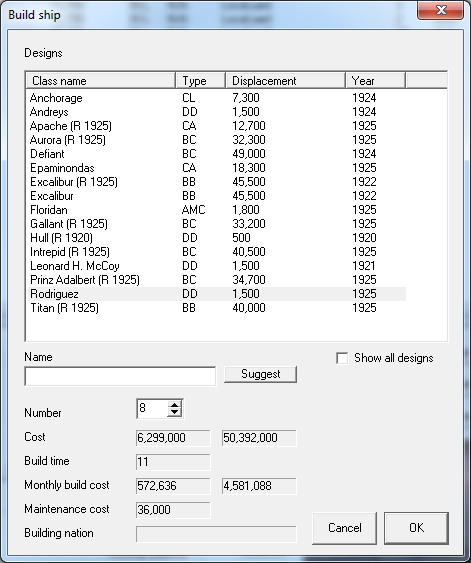

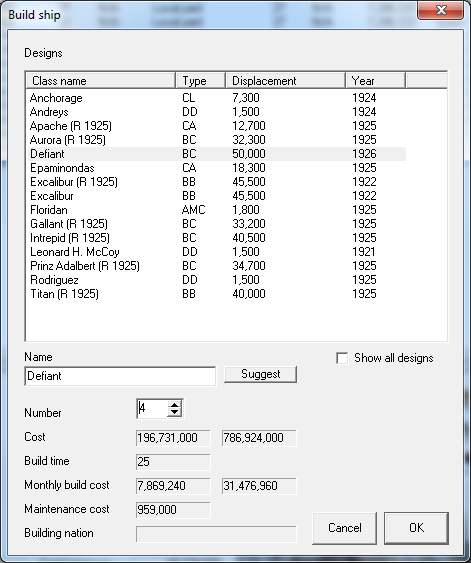

In light of the losses in cruisers and destroyers, the growing windfall in the naval budget prompted the Office of Naval Design and Procurement to focus on construction of more vessels of these types. Four more Anchorage-class cruisers were laid: Las Vegas, Fairbanks, Olympia, and San Jose.

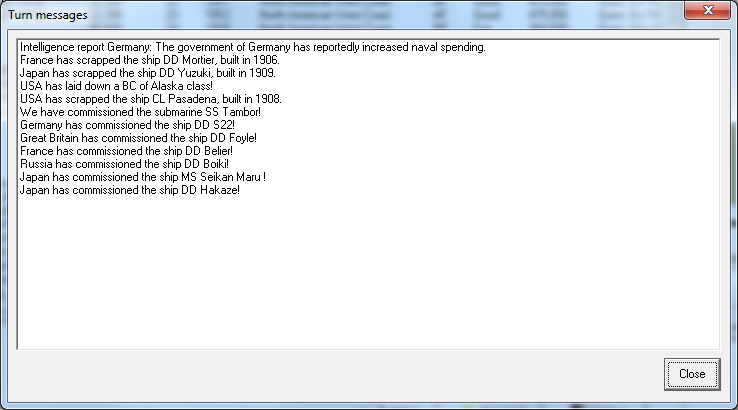

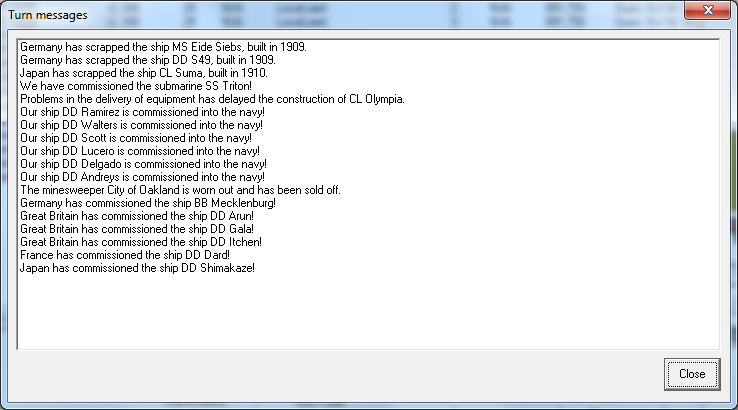

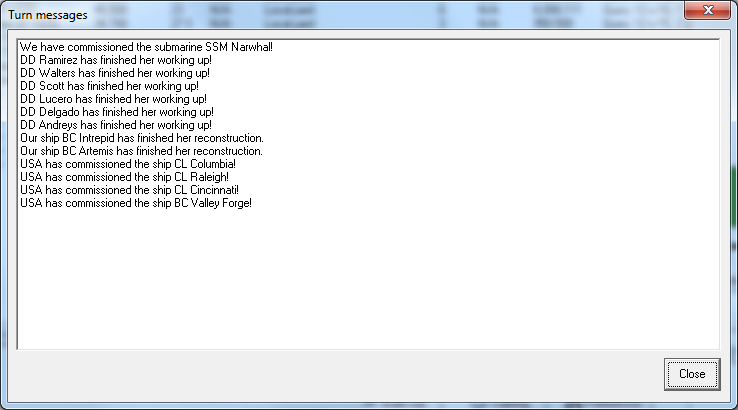

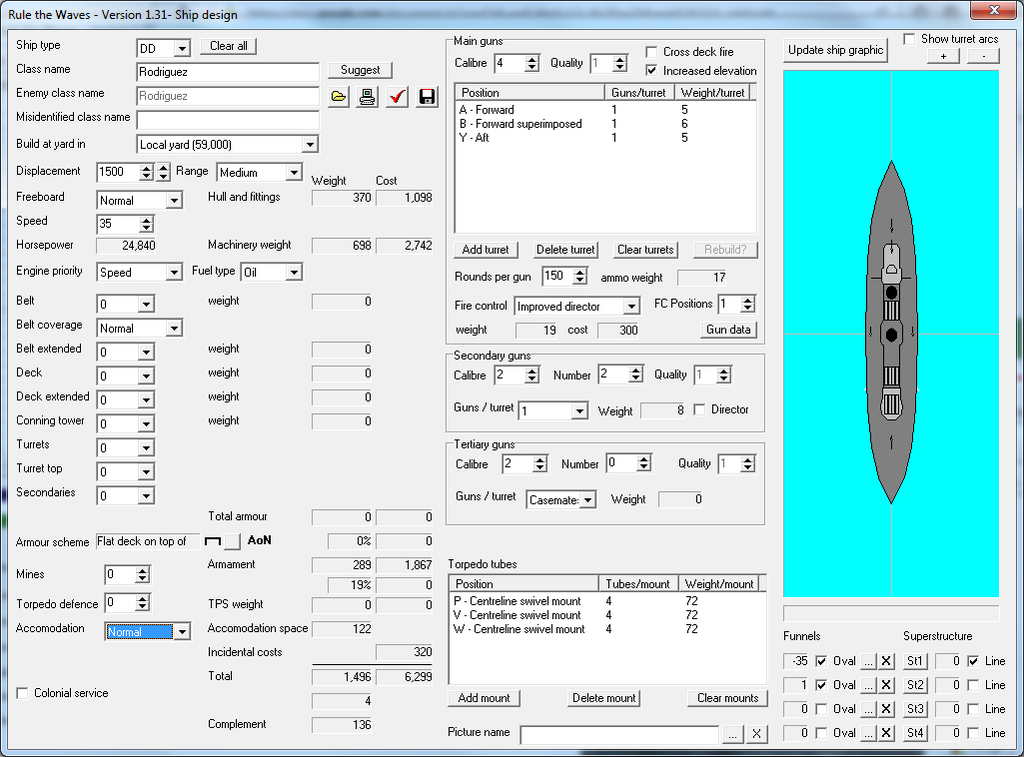

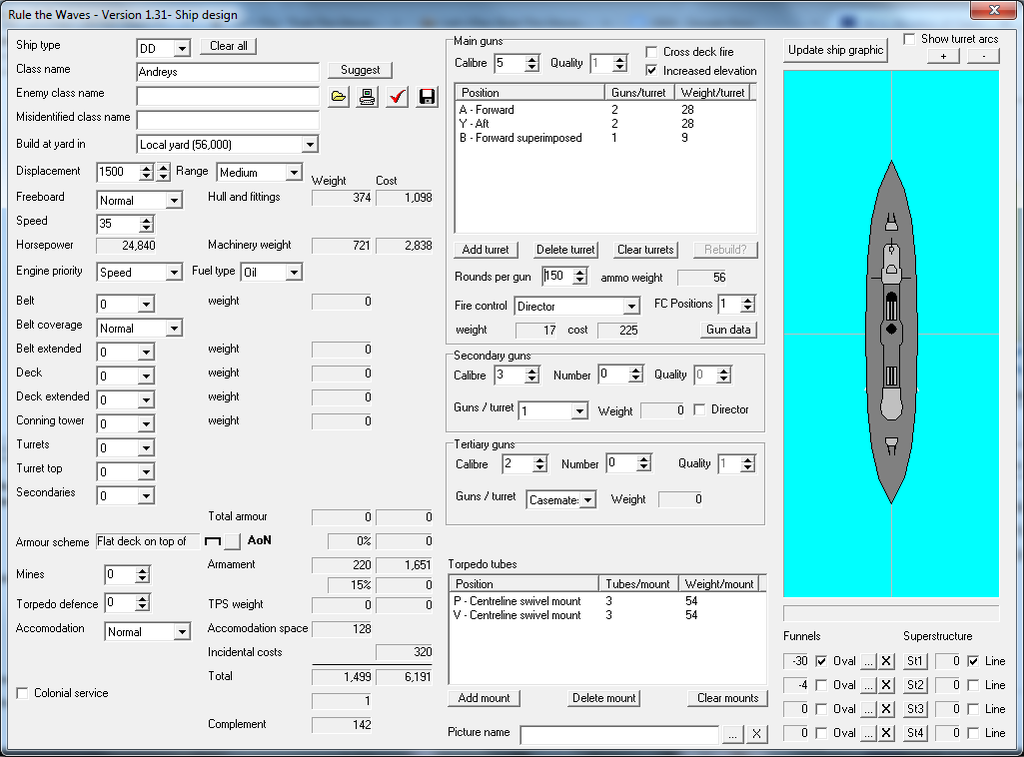

Additionally, a new class of destroyers was ordered. The new Andreys-class destroyer would sacrifice a triple torpedo mount from the McCoy to allow for a heavier machinery plant, providing the ship a maximum speed of 35 knots. Although with only two triple torpedo mounts, the Andreys kept the McCoy's gun armament of 5" guns arranged in two double turrets on the bow and aft and a single super-imposed 5" turret on the bow.

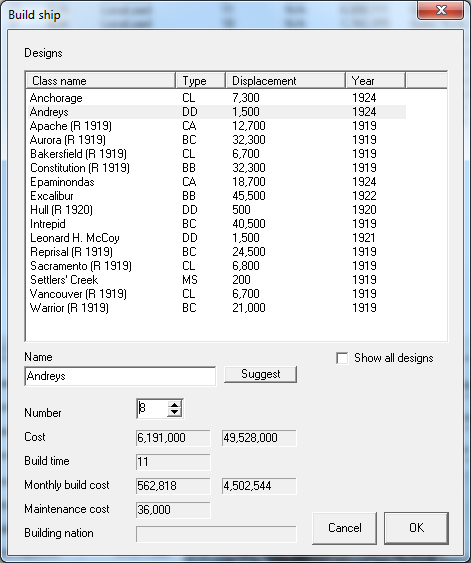

Eight ships of the class were laid: Andreys, Delgado, Carrey, Lucero, Scott, Walters, Ramirez, and Bucher.

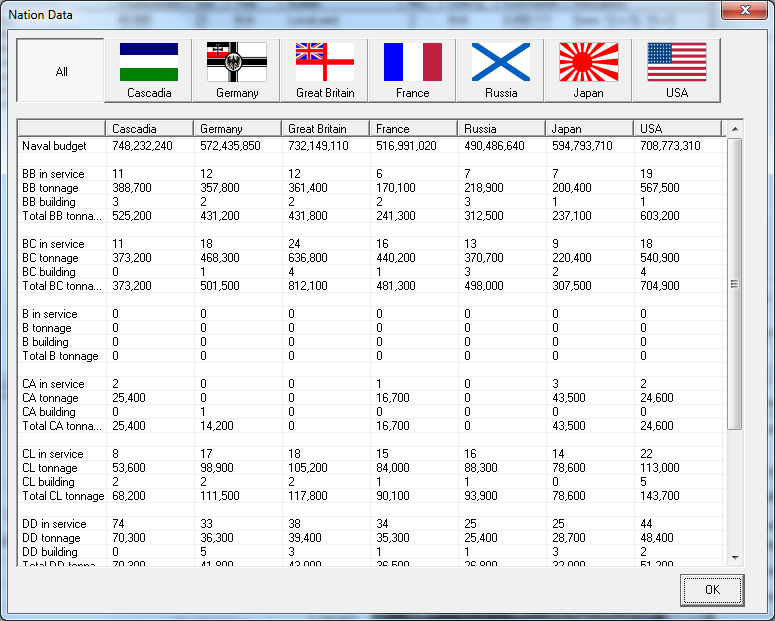

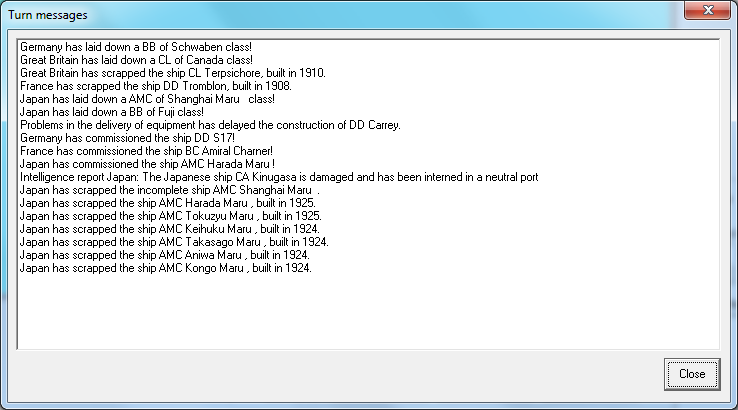

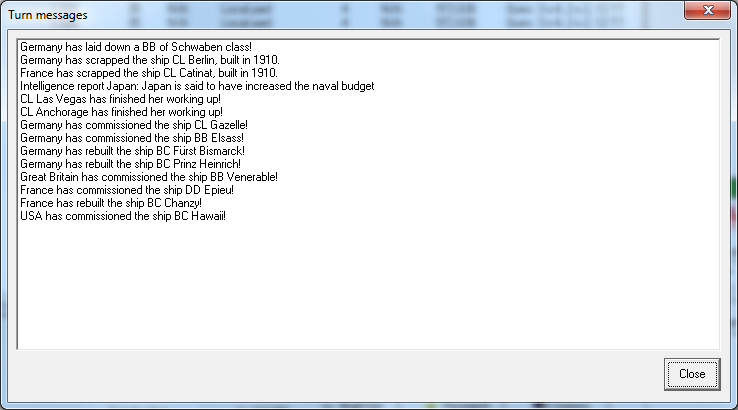

Status of the World as of August 30th (Prior to Cascadian orders to end the month):