Simon_Jester wrote: 2017-10-03 06:29pm

Everyone who advances the argument "well, the police can always protect you adequately against criminals, and I don't know what you're complaining about" should be made to read

parables about dogs and geckos on the subject of what "privilege" means until their eyes bleed.

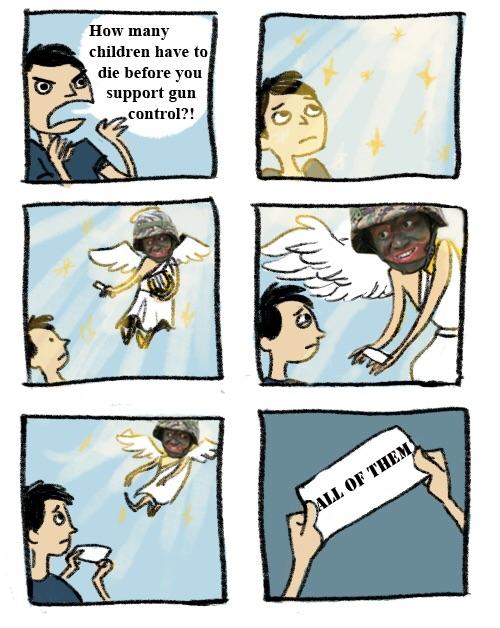

So why is it possible for law enforcement to be sufficiently adequate in other countries that gun-ownership is not required to keep yourself safe? Is the US somehow incapable of matching the Australian law enforcement? Is it not possible for the law enforcement in the US to be improved?

FOR THE RECORD: I am here going to put on the hat of a person who has a firm, unambiguous belief in the right to bear arms. I am going to exaggerate the strength of this belief, so that you are at least presented with a credible challenger in hopes that you will address the argument seriously. This involves me doing a debate-team-esque thing and making claims I personally do not fully believe, for the sake of playing the role of the "gun rights guy." Please, everyone, be aware that I am doing this, for the sake of us actually being able to have a meaningful debate on this issue.

I, Gun Rights Guy, would argue that bearing arms is a human right, at least for full citizens of the state they occupy, and should only be denied in specific cases where there is unusual reason to think a person incapable of exercising this right without unusual harm to bystanders.

And yes, even though I, Gun Rights Guy, believe that this is a universal human right, I acknowledge that democratic countries can function without gun ownership. That's not unusual. Democratic countries can function without a lot of human rights being fully in place.

I, Gun Rights Guy, would argue that democratic countries can function when the vote is restricted to certain fractions of the population, too. Many nineteenth-century republics were functional in that their governments did not collapse into dictatorship... even though women, racial minorities, and in some cases the poor, could not vote.

This does not mean that modern democracies should restrict the vote once again, as they used to do. Nor does it mean that I, Gun Rights Guy, would approve if they started doing it again. A universal right is not always a right that is respected by the government of your country. Even governments that pride themselves on how humane and enlightened they are may nonetheless disrespect important human rights that don't fit into their mental picture of what "humane and enlightened" means.

That's still no real argument why gun ownership ought to be a right. All you did is to argue about the harms of taking away rights, but not about actually defending or defining why gun ownership ought to be one in the first place.

There are multiple approaches to justifying this, I, Gun Rights Guy, am going to take the opening steps to one of the approaches.

To summarize, I believe there is a flaw in your approach to identifying which things are "rights." The flaw can be rationalized around to preserve rights a person thinks is important... But can still be used easily to justify dropping rights you do not value. This creates inconsistency and intolerance of the rights and needs of others. And it all has its roots in how we decide which things are "rights."

Without first establishing my reason for using a different rule to identify "rights," our continued disagreement will be very hard to resolve.

...

So what's stopping people from randomly declaring anything they want to do as a "right"? What is the difference between a "right" and merely a "want"?

In particular, I see a flaw in the way you regard things as being rights because they are 'essential,' and that nonessential rights are things to be withheld as privileges, presumably by the state. This definition is problematic, because you can live without a lot more things than you realize.

You use free speech as an example of something democratic society "cannot really function without." This invites two related questions. One is, what do you mean by "really?" How low-functioning does a society have to be before we say "this isn't really functional, people have a right not to experience this?" For example, one-party tyranny is a very stable form of government! Countries have lasted for decades without collapsing into anarchy under one-party rule. Is it really true to say that a society "is not really functioning" just because it's under single-party rule due to the lack of free speech?

Any functioning societies require restricting things from individuals. The idea of the state existing in the first place requires it to monopolize violence. Determining how much access people have to violence is pretty much one of the very basic purposes of the state. States that couldn't monopolize violence cease to exist in any functional way.

So it boils down to what are the thing people cannot live without? What is the baisc, primary necessities that everyone wants to have? What are the trade-off people have to make?

Does one-party system provide the things that people want? Perhaps, but that comes at a trade-off in giving up free speech. If people think that democracy is fundamental, then the structure of the society have to take that into account to make such a system work in the first place.

Secondly, why "democratic" societies? Why is tyranny unacceptable in and of itself? What about tyranny makes it so bad? Your model doesn't have a good answer for this, so while you can use it to justify why people have a right to food and shelter, you can't use it to justify why they have a right to free speech or due process. A society that lacks due process and free speech can be quite functional, in that the average citizen leads a productive life, raises children and so on. In China, freedom of speech is severely curtailed, but society is 'functional.' Arguably more functional than it is in some nominally democratic countries, certainly more so than in some democracies of the past. Why do we have any preference for democracy over tyranny, if all that matters is that we are provided with the things we can't live without? Sure, there's an instrumental argument that democracy provides the necessities better on average... but that is not a good argument for opposing tyranny as such.

The notion of autocratic rule is not in itself unacceptable. The question is what sort of society people are happy to live in. There are people that are happy to trade freedom of speech for greater security (be it perceived or real). Freedom of speech is needed for democratic society to function, which is different from society itself.

The decision to basically forgo freedom of speech lies in the idea that giving up that would ensure greater security, or in a way allow people to access other basic rights such as sufficient food, proper housing, and safety.

I don't feel you have satisfactory answers to these questions, so I propose an alternate definition of "rights" that DOES answer them.

Rights exist to ensure the security, dignity, and autonomy of the individual.

...

A right which is necessary to the basic security, dignity, and autonomy of the individual is a right, regardless of whether we can in some sense find a way to live without it.

We can live without free speech, but we cannot live autonomous lives without the freedom to speak, to raise grievances, to propose changes to our way of life.

We can live without the vote, but we cannot have dignified lives, free of subjugation, in such a society. It is a grave offense against human dignity to take fully functional adults and tell them "you are second-class citizens, you have no say in how this country operates."

We can live without guarantees of due process of law in our courts, but the security of accused prisoners is immediately in danger in such a society.

In general, all the 'intangible' rights work far better when viewed as necessary protection for the security, dignity, and autonomy of the individual, than they do when viewed as "things we can't live without." Freedom of speech, freedom from torture, freedom of religion, due process rights, the right to privacy, the right to travel... There are a huge number of such rights, many of them very well recognized by (for example) the U.N.'s Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

To justify why we "cannot really live without" these rights requires tortured arguments full of epicycles. The sad reality is, all these are things we can live without. Most of humanity lived without them for most of history. Many of these rights are things we could theoretically make society "more functional" by selectively ignoring.

But we cannot ignore them and preserve security, dignity, and autonomy for everyone.

Thus, security, dignity, and autonomy of the individual are a much firmer grounding for whether or not something is a "right" than the standard you propose would be.

Ok. So how does gun ownership falls into that? Why is gun ownership fine, but the right to form a private army not allowed? Where do you draw the line between what is allowed and what is banned?

Maybe rural Japan and the rural UK have lower violent crime rates than certain parts of the rural United States.

I mean, suppose a Canadian and a Guatemalan are arguing about building codes

in Nigeria. The Canadian says that the Guatemalans need to enact stricter, more rigorous codes about insulation and heating to keep their buildings warm in the winter. The Guatemalan protests that winter in Guatemala is not very cold, and that Canadian building codes would result in dangerously overbuilt, stuffy, overheated, and uncomfortable buildings by Guatemalan standards.

Is this "Guatemalan exceptionalism?" No, it's basic common sense. If a problem does not exist in my country, I do not need to take special measures to protect against it. Conversely, it is not "Canadian exceptionalism" for the Canadians to feel the need for laws or rights that people in other countries do not desire so strongly, that address specific issues of Canadian climate and culture.

Is it

that heretical to just listen to people who live in an area, or have close family that lives in an area, when they say "the needs of this area include XYZ, and do not include things that you, a city-dweller on the literal other side of the world, think are necessary?" Or when they say "your proposed changes to our society would be actively harmful to us, you don't know enough about our society?"

I mean, follow this pattern far enough and you wind up tearing down whole cities to rebuild them in accordance with

your rectangular grid fetish, and that's such a passe, twentieth-century obsession.

The problem is when you apply the needs for a more rural community onto a more urban city as if there won't be any major consequences. Massed shooting in America has to my limited knowledge, caused by relatively easy access to guns. So what works for a more rural environment can cause huge potential risk and danger to a more urban population. So the question is whether easy access to guns for rural communities is worth the harm caused to an urban population? Before resorting to easy access(relative to other countries) to guns as the primary solution for self-protection for people living in more rural areas, the question is whether it is possible to improve law enforcement that you could potentially not over-rely on guns and self-protection in the first place.

I see it as American exceptionalism because other countries with similar geography like Canada or Australia managed fine with more restrictive gun laws and the people still feel that they can rely on the police force. And if you think that the problem lies with American being more naturally violent than others, how is adding guns into the equation better for people?

Humans are such funny creatures. We are selfish about selflessness, yet we can love something so much that we can hate something.