The initial question is "It's not illegal so you can't take them down", but that ignores that the hosting companies are not utilities nor are they government so they are not bound by such regulations. But hosting companies do try to stick clear of making any sort of policy decisions regarding whose content they serve.

However, this time around a number of companies did decide that 8chan should not be hosted by them. The primary example is CloudFlare, an internet utility company that decided that "enough is enough" and stopped hosting 8chan.

I'm going to skip the rest of the story (the site is now up again) and instead post an interesting article from Stratechery trying to define a thought framework for who should be able to make such moral/ethical choices on who do they serve/promote and who should be considered a utility company.

Stratechery wrote: On Sunday night, when Cloudflare CEO Matthew Prince announced in a blog post that the company was terminating service for 8chan, the response was nearly universal: Finally.

It was hard to disagree: it was on 8chan — which was created after complaints that the extremely lightly-moderated anonymous-based forum 4chan was too heavy-handed — that a suspected terrorist gunman posted a rant explaining his actions before killing 20 people in El Paso. This was the third such incident this year: the terrorist gunmen in Christchurch, New Zealand and Poway, California did the same; 8chan celebrated all of them.

To state the obvious, it is hard to think of a more reprehensible community than 8chan. And, as many were quick to point out, it was hardly the sort of site that Cloudflare wanted to be associated with as they prepared for a reported IPO. Which again raises the question: what took Cloudflare so long?

Moderation Questions

The question of when and why to moderate or ban has been an increasingly frequent one for tech companies, although the circumstances and content to be banned has often varied greatly. Some examples from the last several years:

Cloudflare dropping support for 8chan

Facebook banning Alex Jones

The U.S. Congress creating an exception to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act for the stated purpose of targeting sex trafficking

The Trump administration removing ISPs from Title II classification

The European Union ruling that the “Right to be Forgotten” applied to Google

These may seem unrelated, but in fact all are questions about what should (or should not) be moderated, who should (or should not) moderate, when should (or should not) they moderate, where should (or should not) they moderate, and why? At the same time, each of these examples are clearly different, and those differences can help build a framework for company’s to make decisions when similar questions arise in the future — including Cloudflare.

Content and Section 230

The first and most obvious question when it comes to content is whether or not it is legal. If it is illegal, the content should be removed.

And indeed it is: service providers remove illegal content as soon as they are made aware of it.

Note, though, that service providers are generally not required to actively search for illegal content, which gets into Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, a law that is continuously misunderstood and/or misrepresented.

To understand Section 230 you need to go back to 1991 and the court case Cubby v CompuServe. CompuServe hosted a number of forums; a member of one of those forums made allegedly defamatory remarks about a company named Cubby, Inc. Cubby sued CompuServe for defamation, but a federal court judge ruled that CompuServe was a mere “distributor” of the content, not its publisher. The judge noted:

The requirement that a distributor must have knowledge of the contents of a publication before liability can be imposed for distributing that publication is deeply rooted in the First Amendment…CompuServe has no more editorial control over such a publication than does a public library, book store, or newsstand, and it would be no more feasible for CompuServe to examine every publication it carries for potentially defamatory statements than it would be for any other distributor to do so.

Four years later, though, Stratton Oakmont, a securities investment banking firm, sued Prodigy for libel, in a case that seemed remarkably similar to Cubby v. CompuServe; this time, though, Prodigy lost. From the opinion:

The key distinction between CompuServe and Prodigy is two fold. First, Prodigy held itself out to the public and its members as controlling the content of its computer bulletin boards. Second, Prodigy implemented this control through its automatic software screening program, and the Guidelines which Board Leaders are required to enforce. By actively utilizing technology and manpower to delete notes from its computer bulletin boards on the basis of offensiveness and “bad taste”, for example, Prodigy is clearly making decisions as to content, and such decisions constitute editorial control…Based on the foregoing, this Court is compelled to conclude that for the purposes of Plaintiffs’ claims in this action, Prodigy is a publisher rather than a distributor.

In other words, the act of moderating any of the user-generated content on its forums made Prodigy liable for all of the user-generated content on its forums — in this case to the tune of $200 million. This left services that hosted user-generated content with only one option: zero moderation. That was the only way to be classified as a distributor with the associated shield from liability, and not as a publisher.

The point of Section 230, then, was to make moderation legally viable; this came via the “Good Samaritan” provision. From the statute:

(c) Protection for “Good Samaritan” blocking and screening of offensive material

(1) Treatment of publisher or speaker

No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.

(2) Civil liability No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be held liable on account of—

(A) any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected; or

(B) any action taken to enable or make available to information content providers or others the technical means to restrict access to material described in paragraph (1).

In short, Section 230 doesn’t shield platforms from the responsibility to moderate; it in fact makes moderation possible in the first place. Nor does Section 230 require neutrality: the entire reason it exists was because true neutrality — that is, zero moderation beyond what is illegal — was undesirable by Congress.

Keep in mind that Congress is extremely limited in what it can make illegal because of the First Amendment. Indeed, the vast majority of the Communications Decency Act was ruled unconstitutional a year after it was passed in a unanimous Supreme Court decision. This is how we have arrived at the uneasy space that Cloudflare and others occupy: it is the will of the democratically elected Congress that companies moderate content above-and-beyond what is illegal, but Congress can not tell them exactly what content should be moderated.

The one tool that Congress does have is changing Section 230; for example, 2018’s SESTA/FOSTA act made platforms liable for any activity related to sex trafficking. In response platforms removed all content remotely connected to sex work of any kind — Cloudflare, for example, dropped support for the Switter social media network for sex workers — in a way that likely caused more harm than good. This is the problem with using liability to police content: it is always in the interest of service providers to censor too much, because the downside of censoring too little is massive.

The Stack

If the question of what content should be moderated or banned is one left to the service providers themselves, it is worth considering exactly what service providers we are talking about.

At the top of the stack are the service providers that people publish to directly; this includes Facebook, YouTube, Reddit, 8chan and other social networks. These platforms have absolute discretion in their moderation policies, and rightly so. First, because of Section 230, they can moderate anything they want. Second, none of these platforms have a monopoly on online expression; someone who is banned from Facebook can publish on Twitter, or set up their own website. Third, these platforms, particularly those with algorithmic timelines or recommendation engines, have an obligation to moderate more aggressively because they are not simply distributors but also amplifiers.

Internet service providers (ISPs), on the other hand, have very different obligations. While ISPs are no longer covered under Title II of the Communications Act, which barred them from discriminating data on the basis of content, it is the expectation of consumers and generally the policy of ISPs to not block any data because of its content (although ISPs have agreed to block child pornography websites in the past).

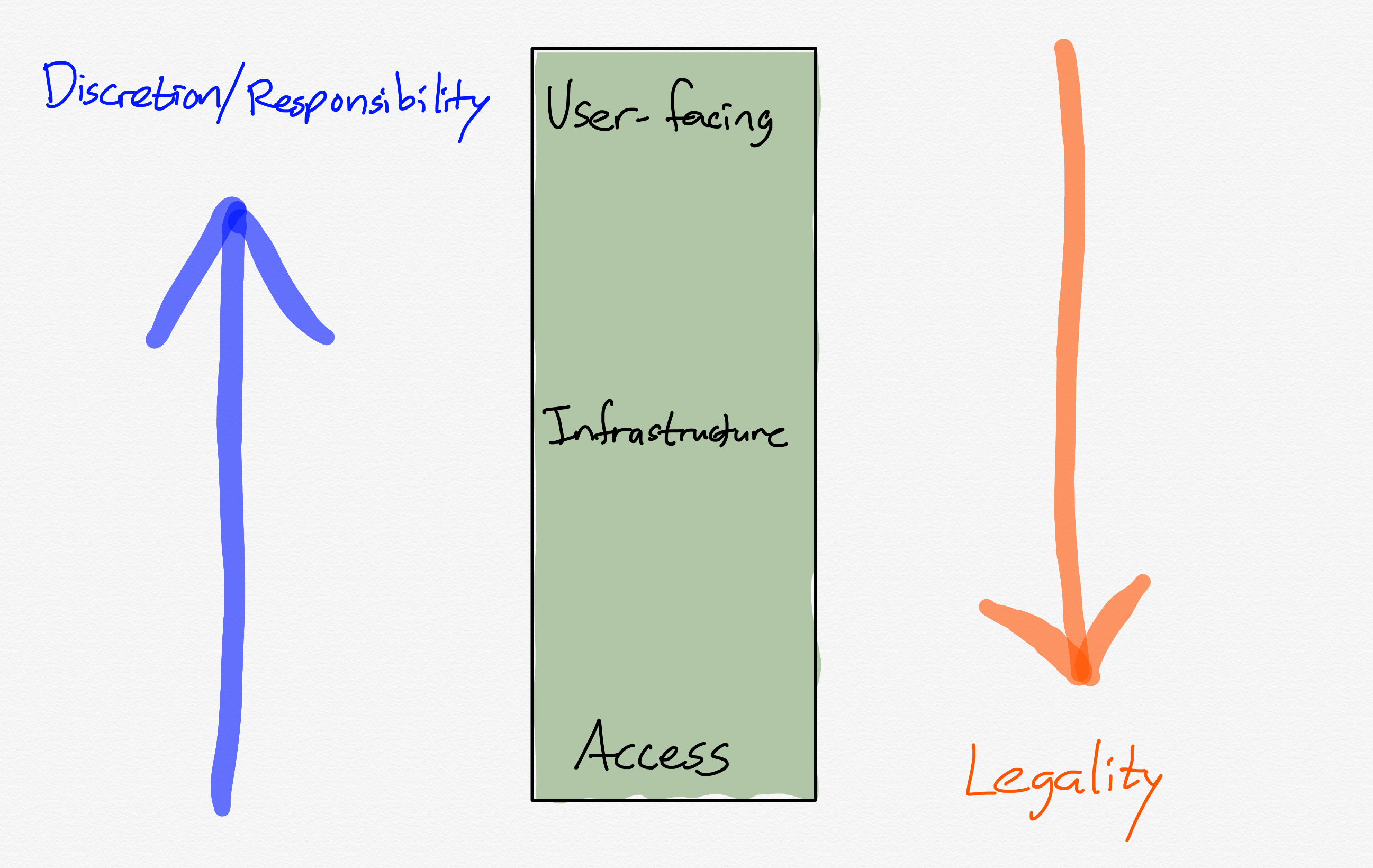

It makes sense to think about these positions of the stack very differently: the top of the stack is about broadcasting — reaching as many people as possible — and while you may have the right to say anything you want, there is no right to be heard. Internet service providers, though, are about access — having the opportunity speak or hear in the first place. In other words, the further down the stack, the more legality should be the sole criteria for moderation; the further up the more discretion and even responsibility there should be for content:

Note the implications for Facebook and YouTube in particular: their moderation decisions should not be viewed in the context of free speech, but rather discretionary decisions made by managers seeking to attract the broadest customer base; the appropriate regulatory response, if one is appropriate, should be to push for more competition so that those dissatisfied with Facebook or Google’s moderation policies can go elsewhere.

Cloudflare’s Decision

What made Cloudflare’s decision more challenging was three-fold.

First, while Cloudflare is not an ISP, they are much more akin to infrastructure than they are to user-facing platforms. In the case of 8chan, Cloudflare provided a service that shielded the site from Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks; without a service like Cloudflare, 8chan would almost assuredly be taken offline by Internet vigilantes using botnets to launch such an attack. In other words, the question wasn’t whether or not 8chan was going to be promoted or have easy access to large social networks, but whether it would even exist at all.

To be perfectly clear, I would prefer that 8chan did not exist. At the same time, many of those arguing that 8chan should be erased from the Internet were insisting not too long ago that the U.S. needed to apply Title II regulation (i.e. net neutrality) to infrastructure companies to ensure they were not discriminating based on content. While Title II would not have applied to Cloudflare, it is worth keeping in mind that at some point or another nearly everyone reading this article has expressed concern about infrastructure companies making content decisions.

And rightly so! The difference between an infrastructure company and a customer-facing platform like Facebook is that the former is not accountable to end users in any way. Cloudflare CEO Matthew Prince made this point in an interview with Stratechery:

We get labeled as being free speech absolutists, but I think that has absolutely nothing to do with this case. There is a different area of the law that matters: in the U.S. it is the idea of due process, the Aristotelian idea is that of the rule of law. Those principles are set down in order to give governments legitimacy: transparency, consistency, accountability…if you go to Germany and say “The First Amendment” everyone rolls their eyes, but if you talk about the rule of law, everyone agrees with you…

It felt like people were acknowledging that the deeper you were in the stack the more problematic it was [to take down content], because you couldn’t be transparent, because you couldn’t be judged as to whether you’re consistent or not, because you weren’t fundamentally accountable. It became really difficult to make that determination.

Moreover, Cloudflare is an essential piece of the Facebook and YouTube competitive set: it is hard to argue that Facebook and YouTube should be able to moderate at will because people can go elsewhere if elsewhere does not have the scale to functionally exist.

Second, the nature of the medium means that all Internet companies have to be concerned about the precedent their actions in one country will have in different countries with different laws. One country’s terrorist is another country’s freedom fighter; a third country’s government acting according to the will of the people is a fourth’s tyrannically oppressing the minority. In this case, to drop support for 8chan — a site that was legal — is to admit that the delivery of Cloudflare’s services are up for negotiation.

Third, it is likely that at some point 8chan will come back, thanks to the help of a less scrupulous service, just as the Daily Stormer did when Cloudflare kicked them off two years ago. What, ultimately is the point? In fact, might there be harm, since tracking these sites may end up being more difficult the further underground they go?

This third point is a valid concern, but one I, after long deliberation, ultimately reject. First, convenience matters. The truly committed may find 8chan when and if it pops up again, but there is real value in requiring that level of commitment in the first place, given said commitment is likely nurtured on 8chan itself. Second, I ultimately reject the idea that publishing on the Internet is a fundamental right. Stand on the street corner all you like, at least your terrible ideas will be limited by the physical world. The Internet, though, with its inherent ability to broadcast and congregate globally, is a fundamentally more dangerous medium. Third, that medium is by-and-large facilitated by third parties who have rights of their own. Running a website on a cloud service provider means piggy-backing off of your ISP, backbone providers, server providers, etc., and, if you are controversial, services like Cloudflare to protect you. It is magnanimous in a way for Cloudflare to commit to serving everyone, but at the end of the day Cloudflare does have a choice.

To that end I find Cloudflare’s rationale for acting compelling. Prince told me:

If this were a normal circumstance we would say “Yes, it’s really horrendous content, but we’re not in a position to decide what content is bad or not.” But in this case, we saw repeated consistent harm where you had three mass shootings that were directly inspired by and gave credit to this platform. You saw the platform not act on any of that and in fact promote it internally. So then what is the obligation that we have? While we think it’s really important that we are not the ones being the arbiter of what is good or bad, if at the end of the day content platforms aren’t taking any responsibility, or in some cases actively thwarting it, and we see that there is real harm that those platforms are doing, then maybe that is the time that we cut people off.

User-facing platforms are the ones that should make these calls, not infrastructure providers. But if they won’t, someone needs to. So Cloudflare did.

Defining Gray

I promised, with this title, a framework for moderation, and frankly, I under-delivered. What everyone wants is a clear line about what should or should not be moderated, who should or should not be banned. The truth, though, is that those bright lines do not exist, particularly in the United States.

What is possible, though, is to define the boundaries of the gray areas. In the case of user-facing platforms, their discretion is vast, and responsibility for not simply moderation but also promotion significantly greater. A heavier-hand is justified, as is external pressure on decision-makers; the most important regulatory response is to ensure there is competition.

Infrastructure companies, meanwhile, should primarily default to legality, but also, as Cloudflare did, recognize that they are the backstop to user-facing platforms that refuse to do their job.

Governments, meanwhile, beyond encouraging competition, should avoid using liability as a lever, and instead stick to clearly defining what is legal and what isn’t. I think it is legitimate for Germany, for example, to ban pro-Nazi websites, or the European Union to enforce the “Right to be Forgotten” within the E.U. borders; like most Americans, I lean towards more free speech, not less, but governments, particularly democratically elected ones, get to make the laws.

What is much more problematic are initiatives like the European Copyright Directive, which makes platforms liable for copyright infringement. This inevitably leads to massive overreach and clumsy filtering, and favors large platforms that can pay for both filters and lawyers over smaller ones that cannot.

None of this is easy. I am firmly in the camp that argues that the Internet is something fundamentally different than what came before, making analog examples less relevant than they seem. The risks and opportunities of the Internet are both different and greater than anything we have experienced previously, and perhaps the biggest mistake we can make is being too sure about what is the right thing to do. Gray is uncomfortable, but it may be the best place to be.