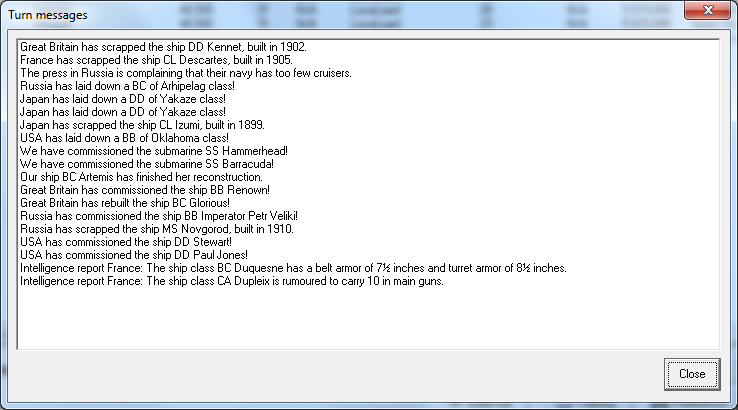

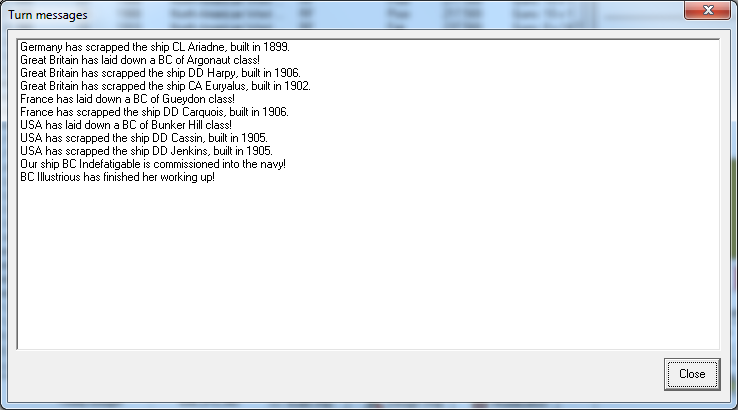

January 1924

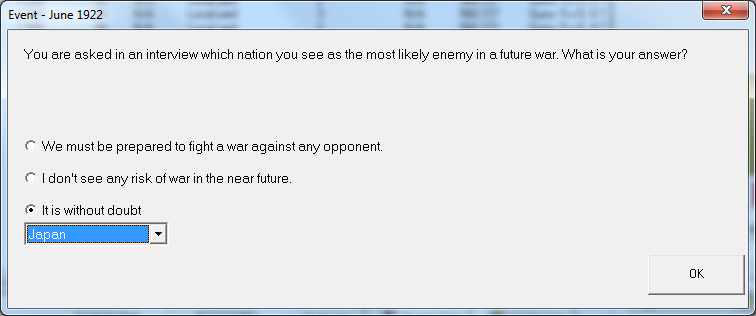

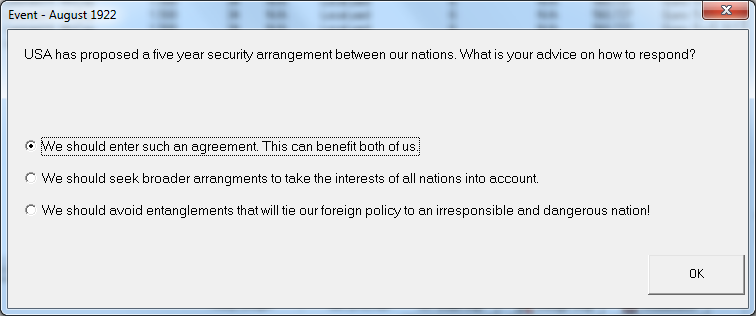

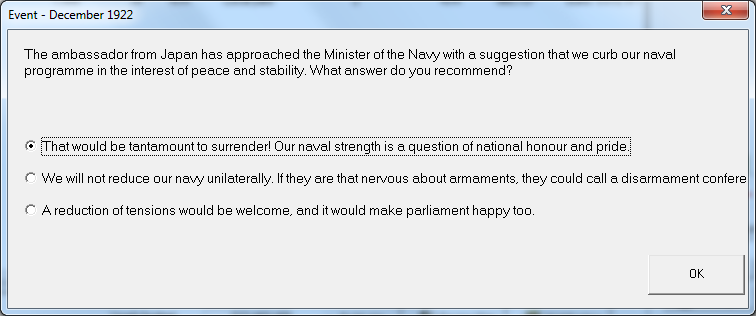

After New Year's, President Muniz and Secretary of State Montelbano met with Ambassador Saito of Japan. The situation was critical; the Japanese government, under increasing militarist pressure, had criticized the Cascadians for sending the 1st Guard Division to Tsingtao, declaring the act "An aggressive deployment meant to destabilize the balance of power in China". As the decision had been made as a concession to Japanese concerns, the criticism stung both men bitterly, and they were determined not to bend to Japanese demands.

Ambassador Saito had his work cut out for him. History could not fault him for his actions, though, as his grasp of the situation led him to make moderate proposals that, in calmer times, would have settled the dispute. But now they seemed to be concessions entirely in Japan's favor, and the two leaders could not accept them. The Cascadian reply of maintaining the

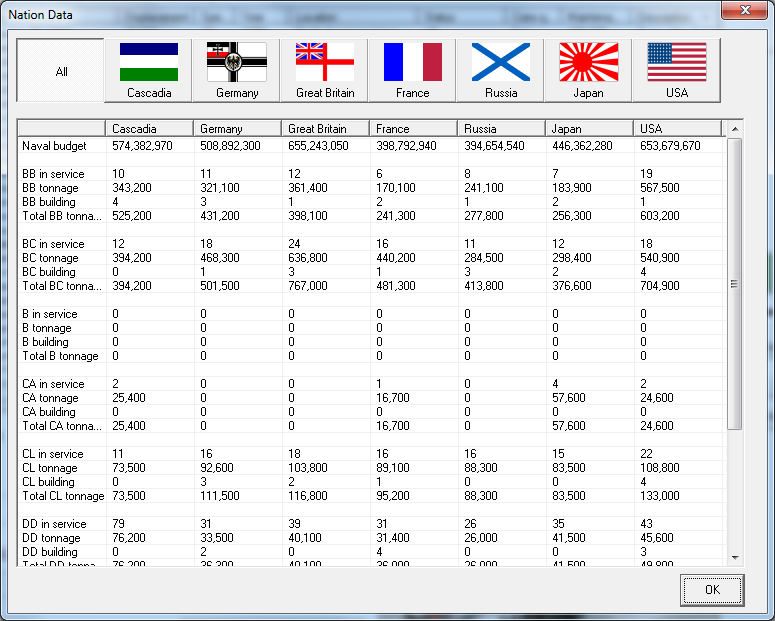

status quo was similarly unacceptable to Japan, not with the Cascadian naval program as it was. The Japanese saw the issue as one of survival: Port Arthur and Tsingtao in Cascadian hands, not to mention Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy, gave the Cascadians strong means to sustain a naval blockade of the Home Islands. Measures to preclude this possibility were necessary to them, but said measures could only serve to undermine Cascadian authority in the Republic's Chinese concessions, and ultimately to leave them vulnerable to Japanese power.

By the end of the first week of the month, it was clear to both sides that the impasse had become unbreakable. Sensing what this meant, President Muniz offered to freeze all further military developments and invite British arbitration of Chinese issues if Japan agreed to pull some of the troops away from Liaotung. Time might yet find a way out of the situation.

Saito received a signal from Tokyo: further talks are acceptable, and Japan would not send further troops. But the military chiefs successfully pointed out the meaningless of this: only the 5th Infantry Division currently held the Peninsula, while the Japanese had several times their number in position to launch an immediate attack or to support an attack with reserves. "We must send in the 1st Guards, or we should just sign away the Peninsula," General Brewer declared.

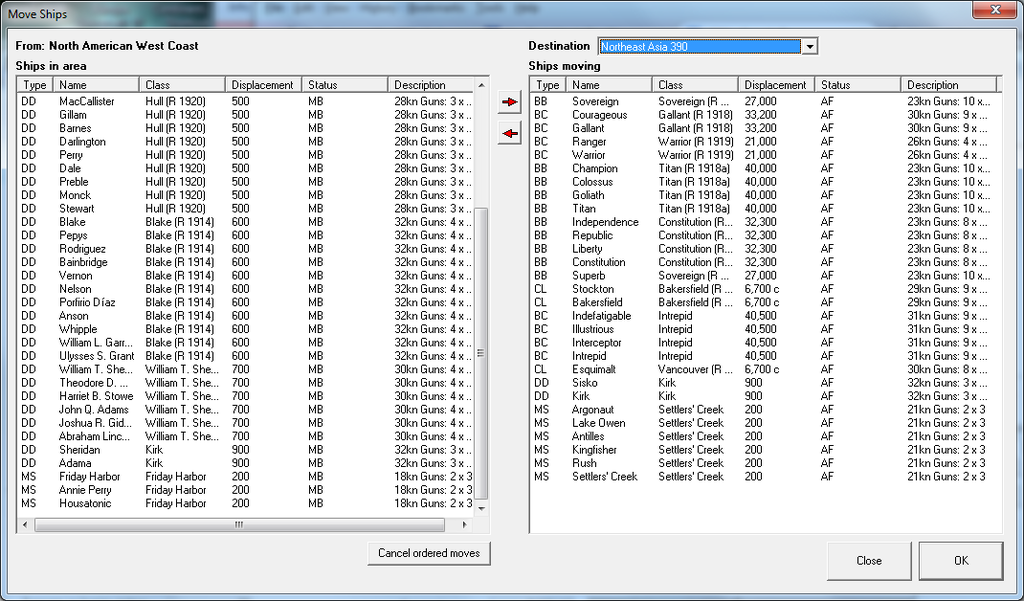

Muniz would later state that he didn't believe that holding both Liaotung and Tsingtao was worth the cost that would be incurred. Whatever he later believed, at this point he acted in line with Hawk mentalities. The Republic would continue negotiation, but it would not be bullied. He ordered Admiral Garrett to dispatch the Battle Fleet to Chinese waters, accompanied by two more divisions in transports. A limited call-up of ten more divisions was ordered, to provide a reserve for further East Asian military action.

The orders went out and the reservists and draftees reported for service. The Fleet departed from its ports in San Francisco and Bremerton. The last two years of preparation paid off - with the assistance of pre-arranged course information and short-range wireless, the two forces rendezvoused in the Pacific en route to Pearl Harbor for the first leg of the journey to China.

By this point in time, the Japanese government had lodged official protests and canceled all naval and army leave. The Japanese fleet made ready to depart its bases for the Yellow Sea. Their goal would be to intercept the Cascadian fleet in Korea Bay and prevent the reinforcements from arriving at Port Arthur.

A dejected Ambassador Saito turned in his passports on the 22nd of the month and booked passage home on a British vessel, convinced war had become inevitable. His Cascadian counterpart in Tokyo did the same on the 24th.

The Admiralty

Portland, Federal District

9 January 1924

The Admiralty's leadership had listened to Admiral Garrett's proposal, and all agreed.

Now the assorted leaders - Admiral Litchfield, the Vice CNO; Admiral Jenkins, the Chief of Naval Design and Procurement; Admiral Hawke, the Director of Naval Intelligence; Admiral Farmer, the Chief of Personnel - watched in silence as Admiral Garrett handed the official orders to Admiral Phillip Wallace. "Admiral, the Battle Fleet is yours," he stated, "and with it command of all Cascadian naval forces in the Far East. The war, should it come, will be yours to fight."

"I understand sir," replied Wallace, with most of the Scots brogue faded from his accent. "I will bring the Republic victory."

"I expect nothing less," said the Admiral, who had once been given a similar charge when sent to command the squadron that forced Manila Bay in what was now a very different time.

Salutes were exchanged. Statements of support made. In the end, Admiral Wallace departed, bound for the train to Bremerton and his flagship, the battleship

Titan.

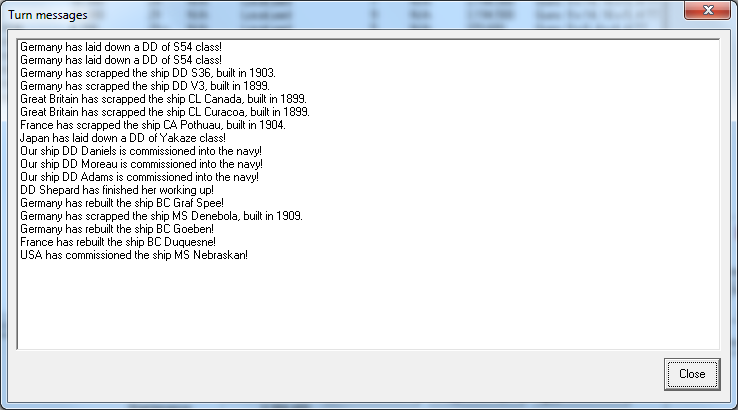

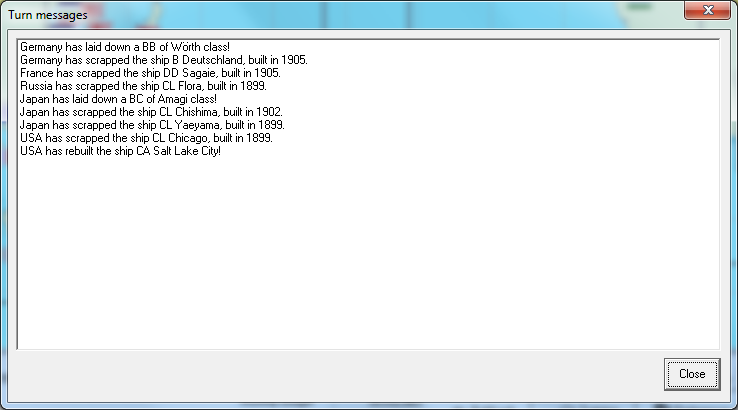

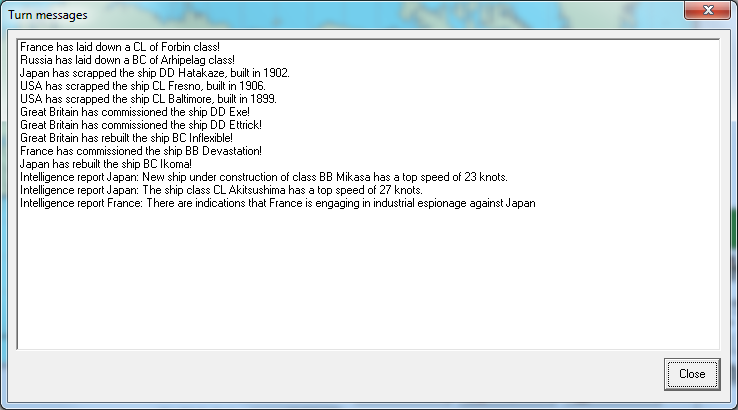

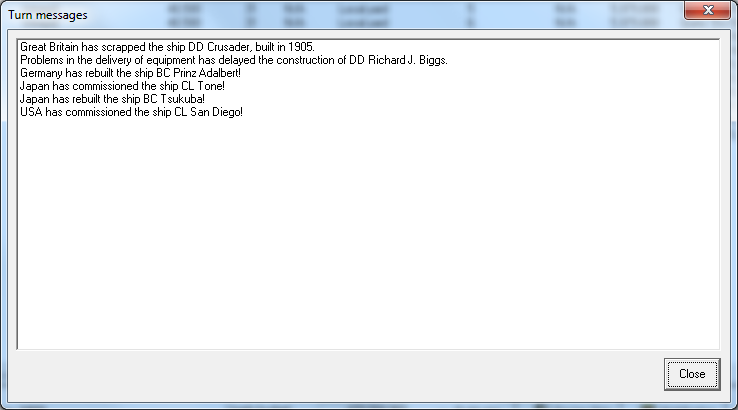

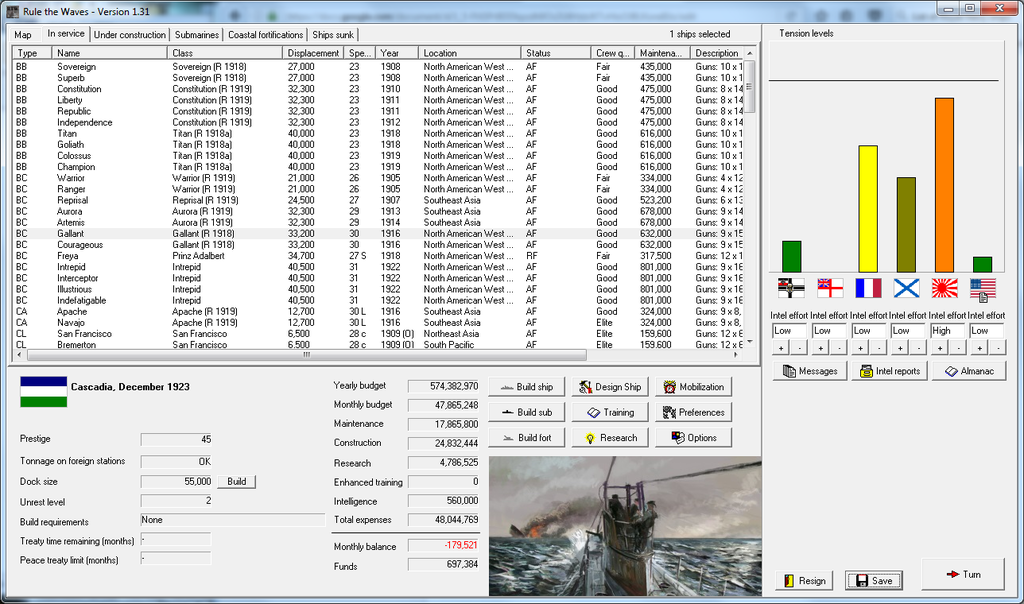

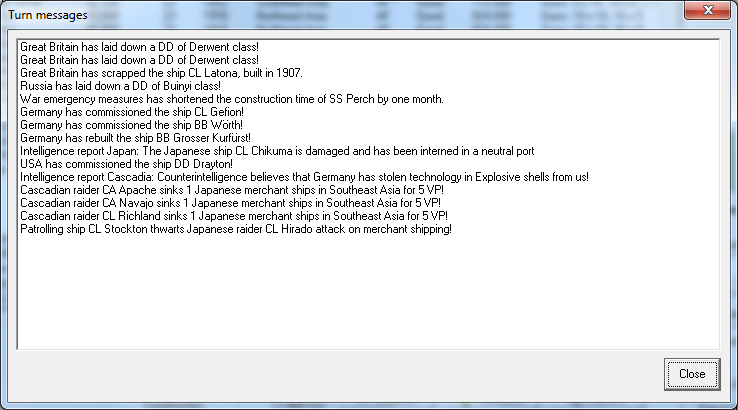

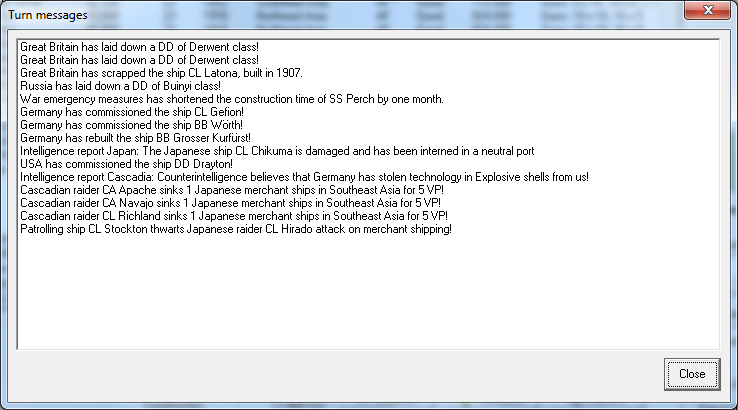

Japan tension to 12

The Garrett House

The Garrett House

West Portland, Oregon

Rafael and Thomas joined the Admiral in the parlor. The two navy men changed into civilian wear. Upstairs Georgie and their children were resting, preparing to depart for Bremerton where Rafael would join Wallace's staff on the

Titan. But tonight, they had other purposes.

It was dark outside when Mei-Ling escorted their visitor in. Professor Walters still had the bushy mustache they'd first seen four years before, the same hairstyle, the same eyes… but there was something to them now. Behind the intelligent eyes shined a new, dark light of some form, like a power that had awakened since they'd last seen the man.

"Professor," the Admiral said in a hard, but neutral, tone.

"Admiral." Walters nodded to them. "I've come to bring my wife home."

"She is home," the Admiral replied.

"Your daughter is… a difficult woman," Walters said. "I admit I allowed weakness to sway me to accepting her charms, but I never knew how deranged she could become. Her injuries…"

"We're not fools, sir," Rafael remarked. "We know the wounds on Sophie were not mere injuries or accidents. You have mistreated her."

"I am her husband. I have responsibilities, the same as her, and I had… trouble with her madness."

"You continue to insult my daughter," the Admiral remarked. "Your defense is not something I believe."

"What you believe is immaterial. What matters is whom the universities will believe," Walters declared. "Will they accept the word of a deranged student over a distinguished professor? If she persists on this course, Sophie's hopes of acceptance into academia will evaporate. Not a single dean or president will stand against me over her." Walters looked to the door. "Did you hear me, Sophie?! Your career is stillborn if you don't stop this foolishness!"

He had been facing toward a door out. But it was a third door that opened, from the kitchens, and Sophie Garrett stepped through. Most of her wounds had been healed over time. But it was still clear she'd suffered with him. She approached him in a plain white blouse and gray skirt. "Theodore," she said.

"Sophie, let's go home. This is between you and me," he insisted.

"Yes," she said. She approached him. "It is." She looked to her father and siblings. "Thank you, Papa, for your help. And yours as well, Thomas, Raffie." Her eyes turned back to Walters and she approached him. "I should have accepted this earlier."

"Yes, you should have," he answered as she approached. He smiled and leaned in slightly to kiss her.

He never saw the punch coming.

Sophie's fist caught him in the jaw. Her other fist found his belly and he fell over. His mouth hung open in shock.

"I am not going back to you, you

beast," she hissed.

Walters remained on the floor a moment. So she continued. "I filed for divorce."

"You must take that back!", he shouted. "A divorce will make us a mockery!"

"We're already a mockery, Theodore." Sophie turned away from him. "I wish we'd never met."

"Turn back here this instant!", Walters screamed. "I mean it!? Right now! Sophie, you can't!"

But she had. Sophie had already left the room. Thomas and Raffie interposed themselves to stop Walters at the door.

"You can't do this," he rasped. "I have rights as her husband!"

"And we have rights and privileges as her family," retorted Raffie. "Now

leave."

The transformation completed before their eyes. The professor's face twisted into a grotesque reflection. His fists clenched and he seemed to draw himself up. He lunged for the door.

The two brothers caught him. He fought back. He fought back hard. He bit, he punched, he kicked at the two. But they were the Admiral's sons, and they were Rachel's sons, and she had not been a small woman - he certainly wasn't even a moderately-sized man, but on the large scale, and his sons had inherited some of that. Walters' lack of size, lack of mass, soon showed against him. Raffie and Thomas threw him to the floor.

He might have lunged again if not for the ominous cocking sound from the table. He turned and faced the Admiral with a hunting shotgun pointed straight ahead. A second cock heralded the arrival of Judy Freeman, a second shotgun in hand, and held by someone who knew what the hell she was doing with it.

"You'd allow that

nigger to shoot me?!", Walters raged.

"She is a part of this household, and has every right to defend it," the Admiral replied plainly. He lowered his own weapon - Judy was, in his estimation, a far better shot, and at 71 years of age he wasn't in the best shape to brandish a weapon. "Leave this house."

"I'm going to destroy that little tramp," the angry man vowed. "I'll destroy her!"

"No, you will not," the Admiral intoned. "You will accept her decision and leave our lives behind."

"

DO YOU KNOW WHO I AM?!"

"A pathetic, sad little man, who took out the frustrations of his life on the woman he swore to cherish," the Admiral remarked. "And ultimately a silly fool who thinks that academic respect can be used as a club. Maybe you're able to cajole and push university leaders into blacklisting my little girl, Professor, but can you do the same to

me?"

And the answer… was mixed. Academics didn't always care for military officials, after all.

On the other hand, many universities enjoyed varying patronage from alma mater and governments, and if it became known that Professor Walters had earned the wrath of the Admiral, there were those who would calculate that losing a respected historian was a lesser evil to gaining the enmity of Cascadia's most respected military officer and the immense number of supporters he enjoyed in politics.

Walters' rage nearly cost him control, but self-preservation at the sight of the gun held toward him overpowered that frustrated rage and humiliation and held it in check. The little man seemed to vibrate at the conflict of these two forces within him as he stormed from the parlor. Thomas and Judy followed him. Soon afterward, the front door slammed.

The Admiral let out a weary sigh. Walters was an unwelcome distraction for him. War with Japan was imminent.

But this was for his daughter, and he had already failed one of his little girls.

He entered the kitchens. Judy's handiwork was mostly cleaned up, and there was a faint smell of cleaning soaps in the air near the sink where Sophie was staring off into space with tear-filled eyes. "I loved him," she mumbled. "I loved him so much. He was so charming, and brilliant, and… and… how could I not see…"

"Men like him hide that beast. They're usually ashamed of it. And that, in the end, only makes the savage creature more powerful."

Without a further word, the Admiral took his weeping daughter into his arms.

February 1924

February 1924

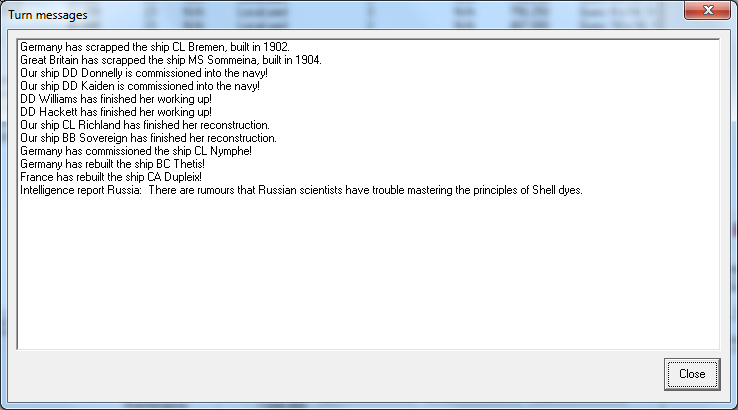

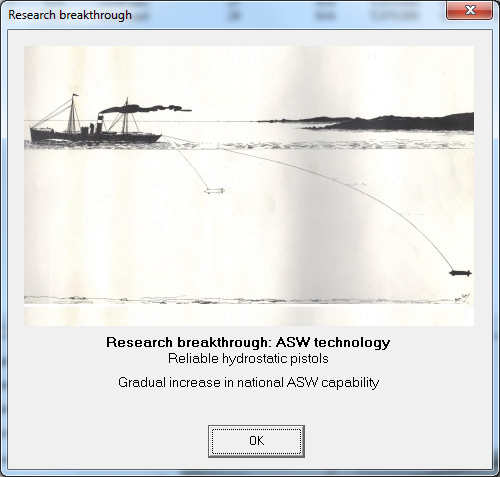

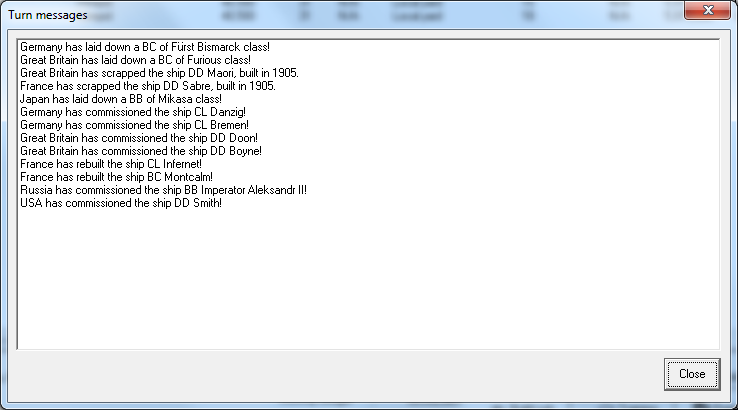

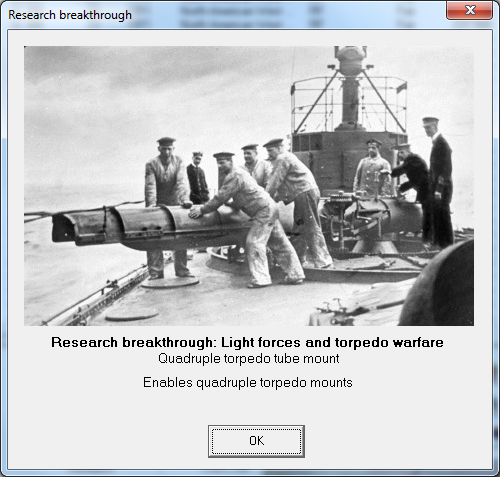

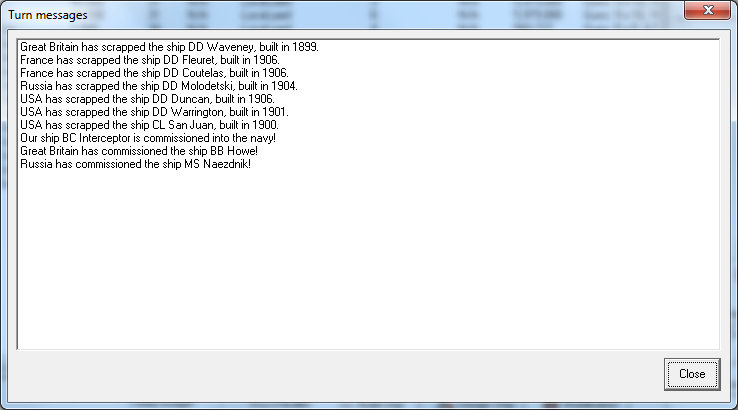

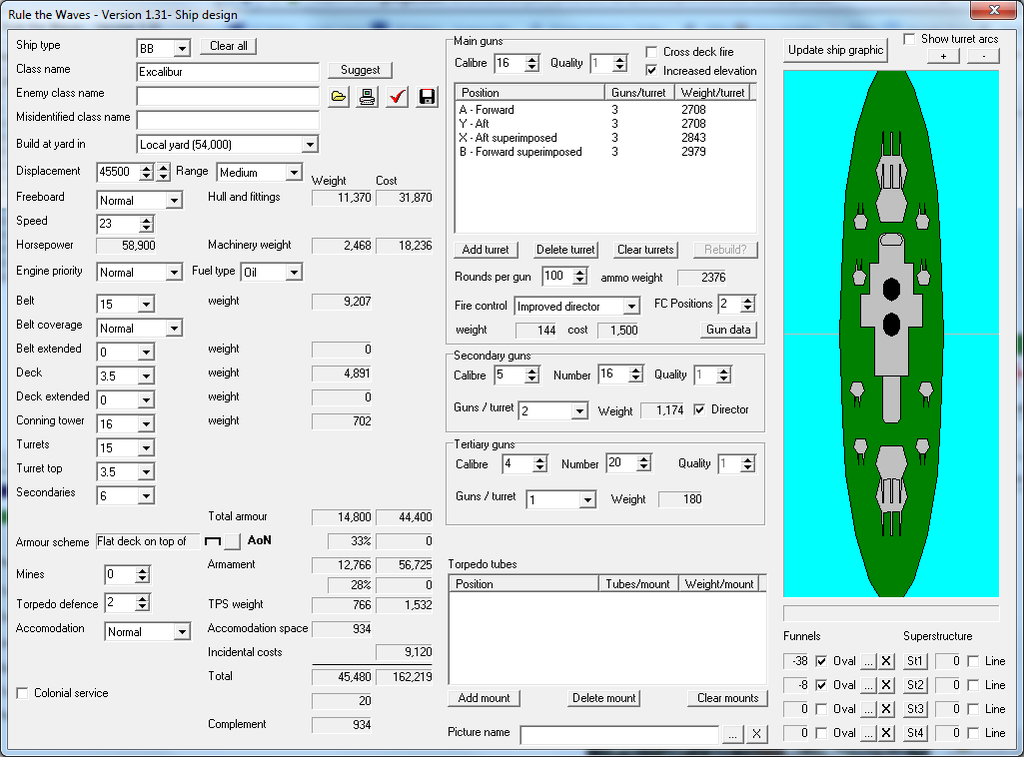

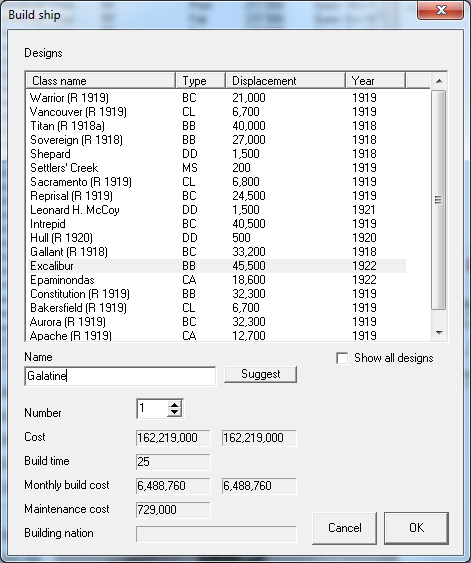

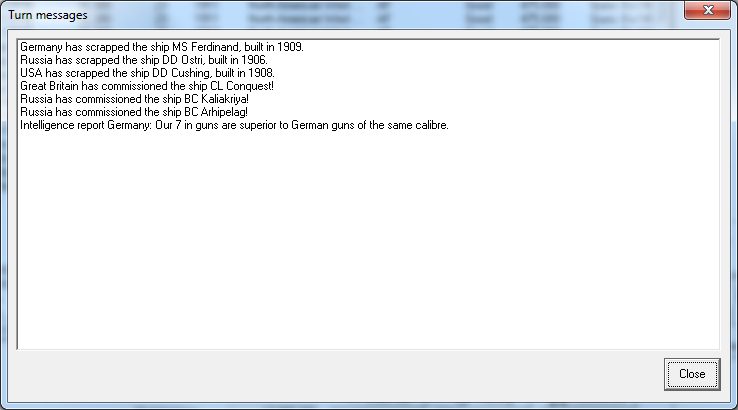

During the month, designers reported they had successfully tested and employed the new anti-sub K-guns. They were ready for fleet use. Naval Artillery announced it had completed prospective testing on a new 18" naval rifle that could one day be employed on battleships above 50,000 tons.

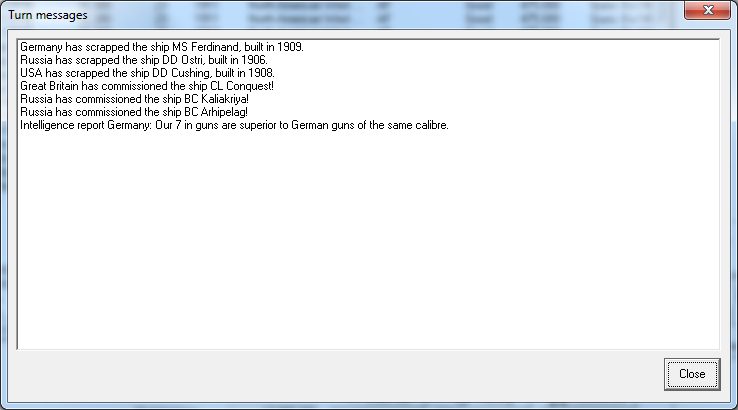

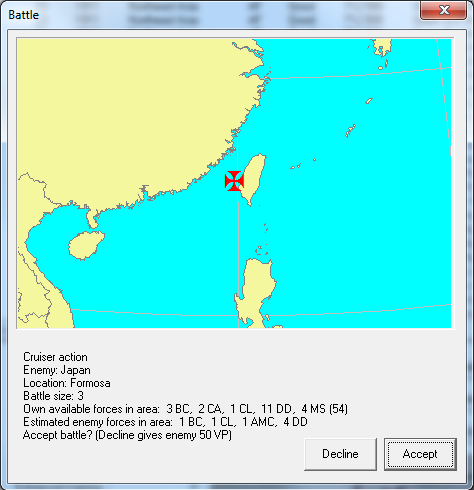

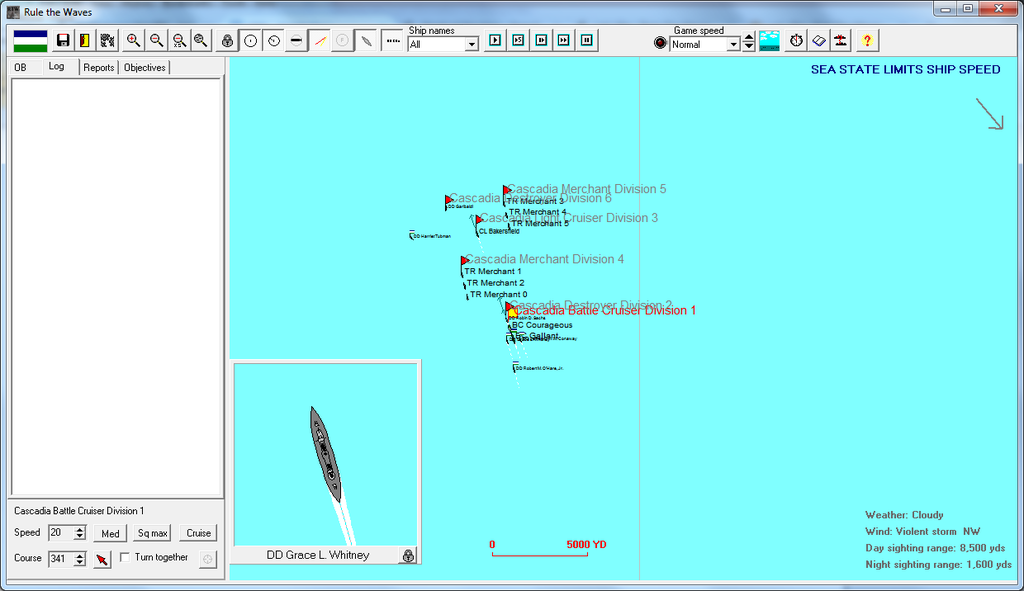

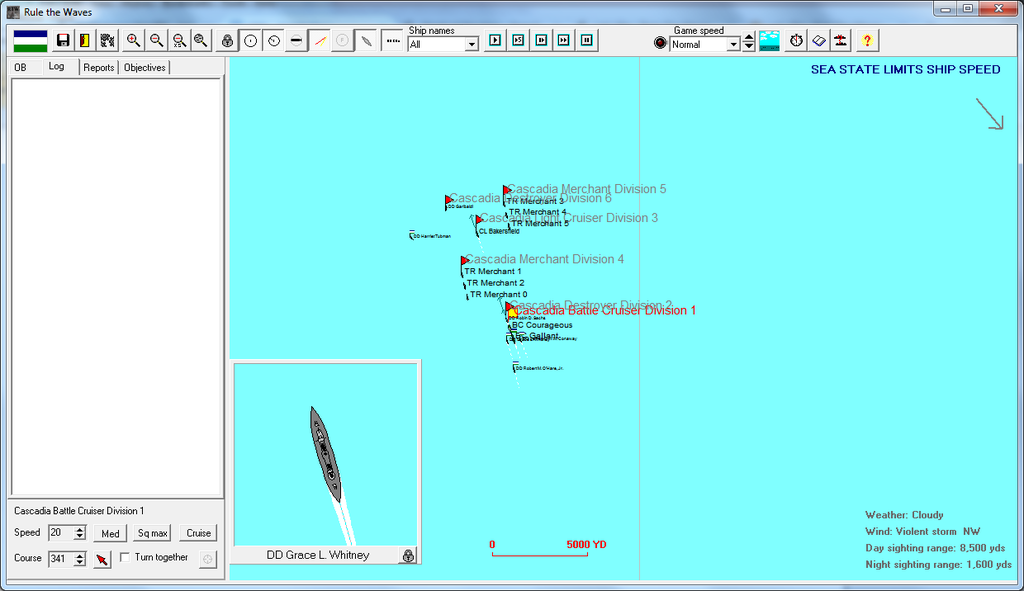

The world waited with baited breath as the Cascadian fleet approached China. The Japanese, hearing via wireless that Wallace's battle line had been seen near Iwo Jima, deployed south to intercept him in the Ryukyus.

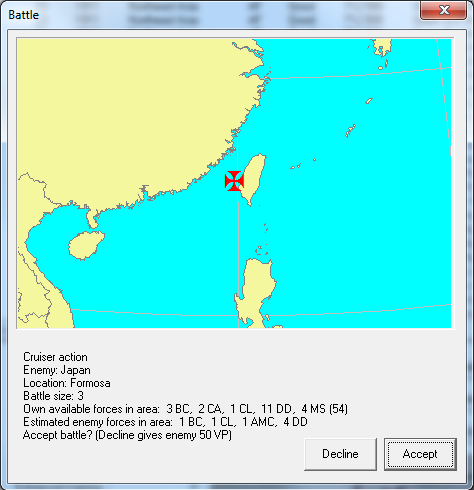

But Wallace opted for the less direct route. He swung southwest and skirted Formosa, slipping through the Japanese cordon. It was a close thing: Japanese cruisers had drawn close enough that they made visual contact. But it was too late; they only did so as Wallace's ships were already past the Ryukyus and sailing for the Yellow Sea, where they rendezvoused with the cruisers of the China Squadron and the transports carrying the 1st Guards Division.

The Japanese fleet turned and chased. Radio signals to shore announced that the Cascadian fleet was entering the Yellow Sea.

Tokyo made the fateful decision on the 13th.

An hour before dawn on the morning of the 14th, artillery cannons roared along the Cascadian-Japanese lines in Liaotung, and elements of three Japanese infantry divisions crashed into the lines of the 5th Division. The Japanese declaration of war against Cascadia was delivered through the British Ambassador thirty minutes before the attack began.

The Cascadian troops in Liaotung had been preparing defenses for months. Veterans of the fighting in Lorraine in 1909 and 1910 remembered the German defenses that had bedeviled them and sought to replicate the same. The Japanese also remembered, of course, and sent infiltration parties ahead with the initial shelling to attack in said trenches. The infiltration attack met with moderate success - the initial Japanese waves overran over half of the trench line of the Cascadian defenses. By the end of the first day of fighting, the Cascadian troops had been driven back by nearly a mile

But the Japanese success had cost them blood, and their Navy's failure to intercept Wallace allowed the Cascadian fleet to bring into Dalniy (Dalian) reinforcements, including the 1st Guards, who disembarked first during the 15th. By the 16th they were being thrown into a localized counterattack that blunted the Japanese offensive and cost them several trenches. The other divisions would be fed into the battle over the next few days, where space allowed - gradually the lines stabilized with Japan still inside the Cascadian Zone by nearly 600 yards, but facing a dug-in foe.

This was not necessarily in Cascadia's favor: feeding and maintaining tens of thousands of troops would require constant re-supply by water, and the Japanese were determined to cut the supply line with a close blockade. Just as much, Wallace was determined to establish, as soon as possible, an effective blockade of Japan itself, for which he required more ships and, perhaps, a victory over Japan's battle fleet.

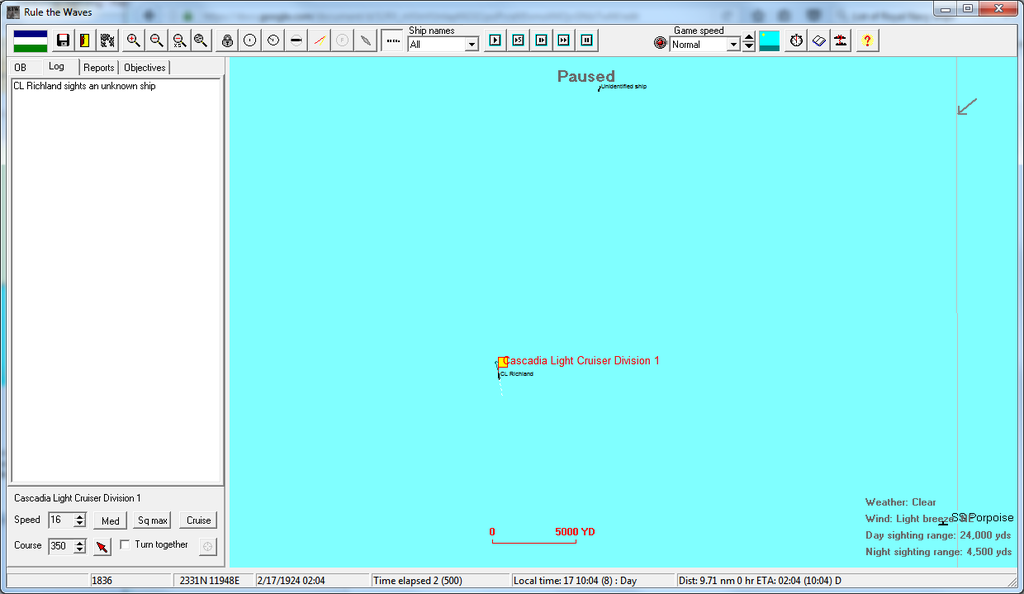

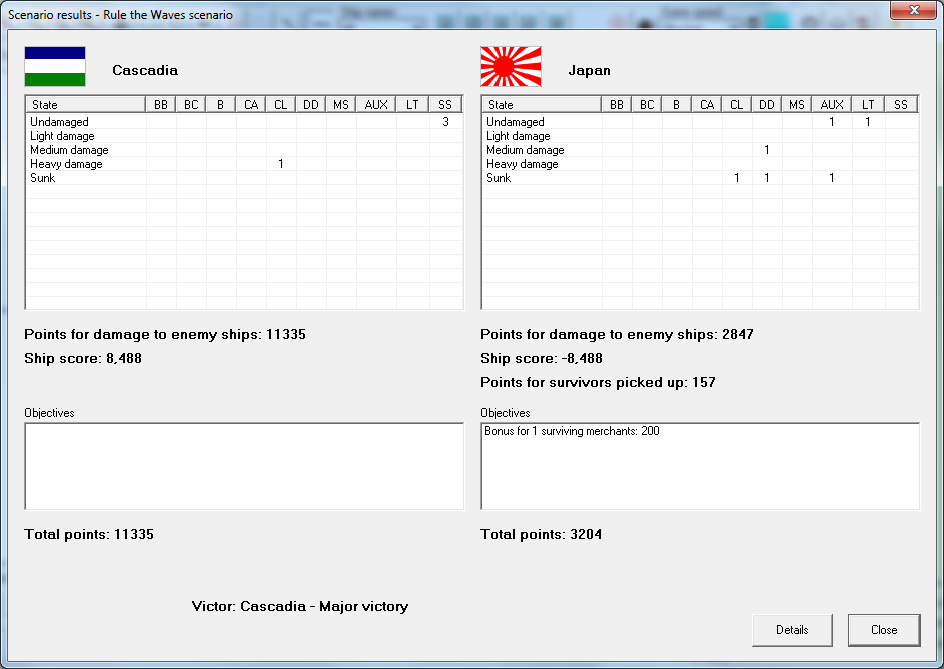

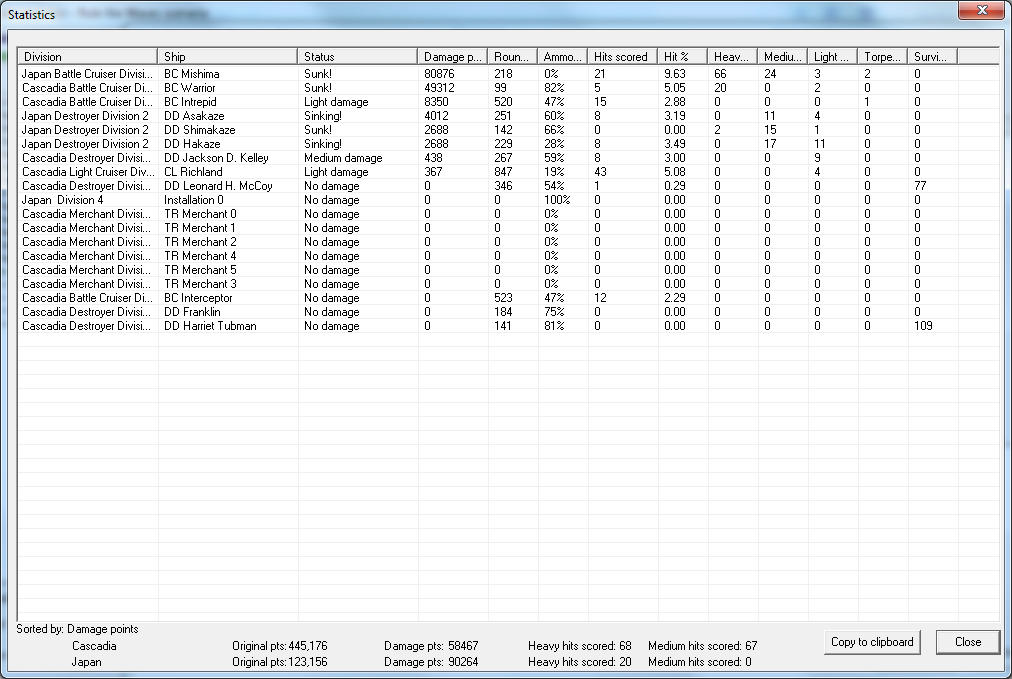

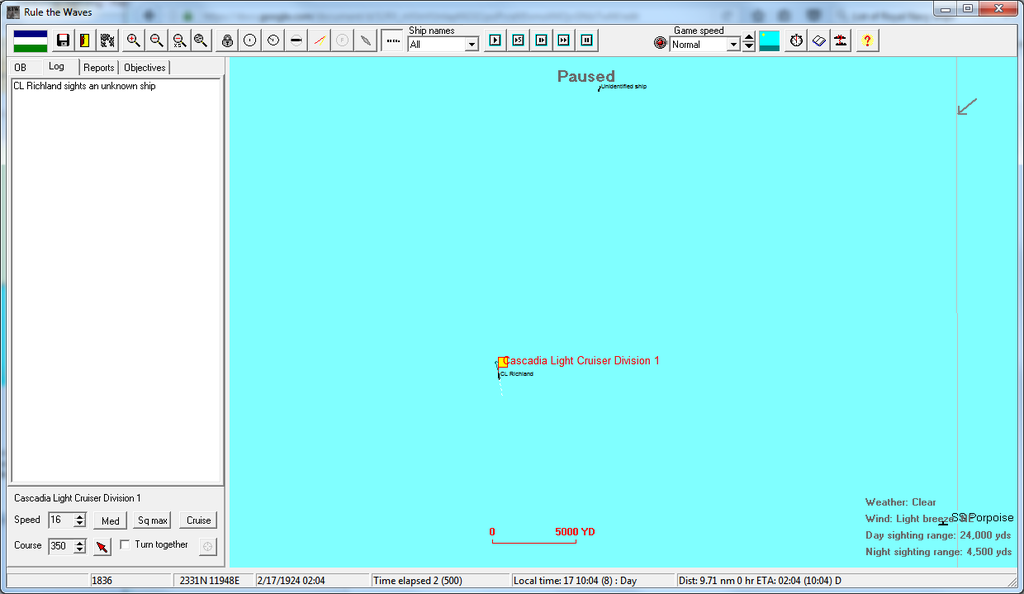

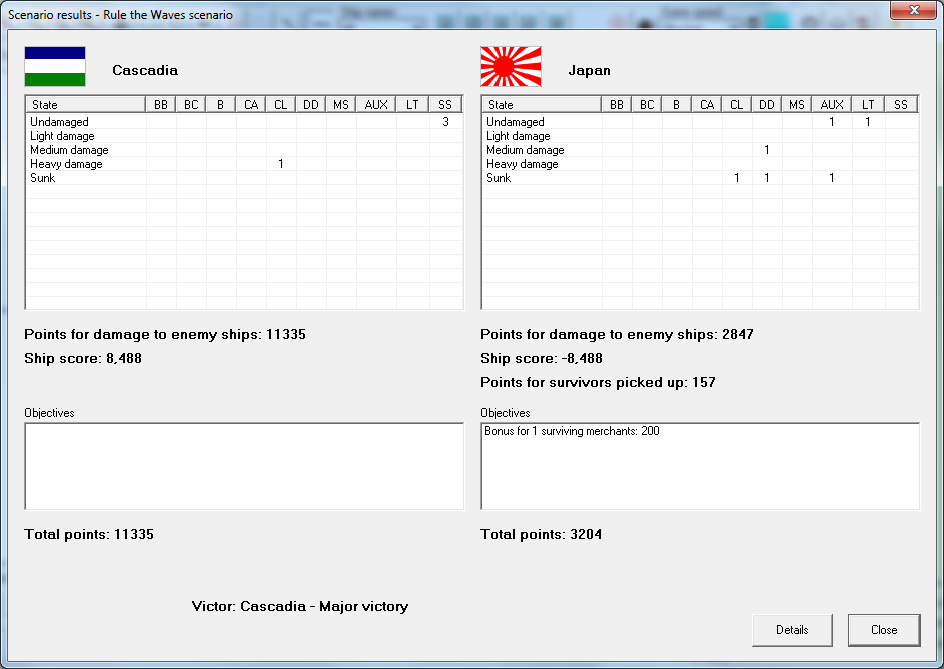

The war on the sea began with a smaller action. On the 17th the

Richland sailed into the Formosa Strait and made contact with the Japanese cruiser

Suma and the destroyers

Tachikaze and

Kamikaze. Although outnumbered, Captain Clarkson gave the order to engage. The

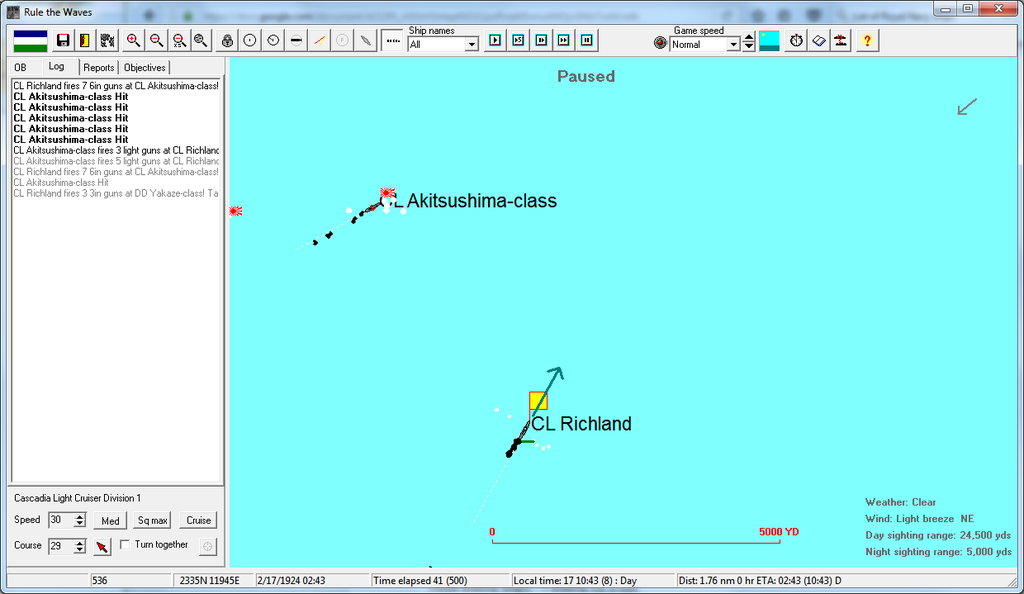

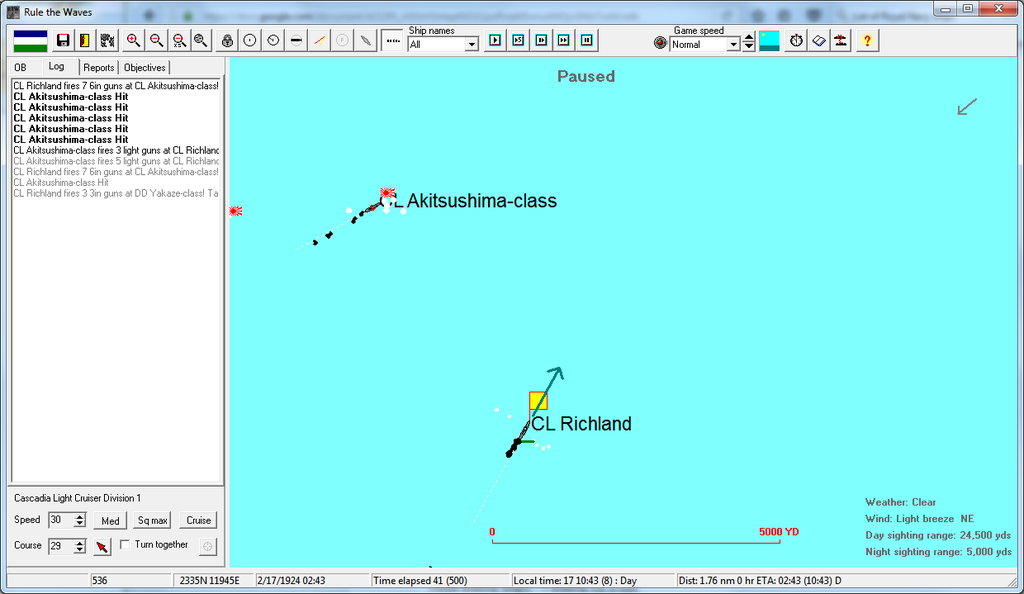

Richland spent the next hour in a fierce battle, landing several hits on the

Suma while enduring enemy fire. The cruiser took hits as well: two shell hits caused salt water to enter feed tanks, and fifty minutes into the battle a shell destroyed

Richland's torpedo tubes.

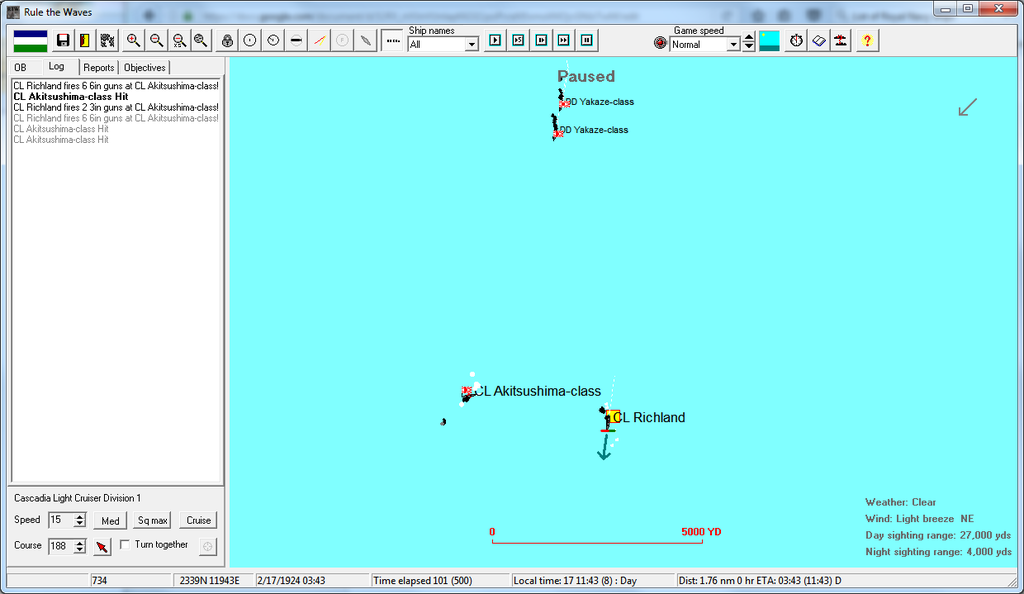

The

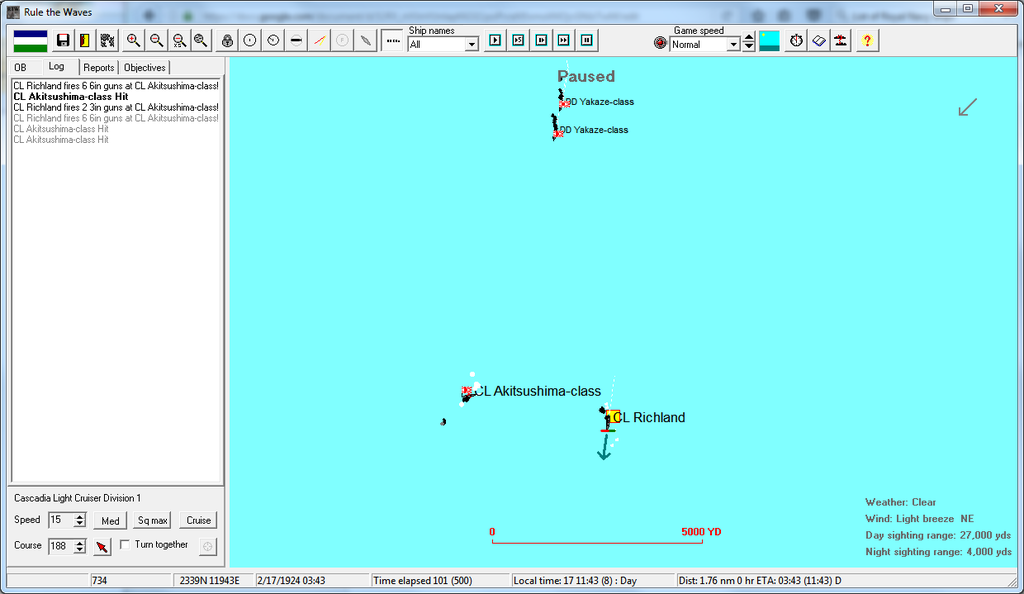

Vancouver-class cruiser was eventually forced to break off from the motionless but still-firing

Suma, moving south and out of visual range of her foes. While doing so she came into proximity of a Japanese merchant vessel. The crew of the ship abandoned their vessel as

Richland approached, making it an easy target.

After the repairs necessary to the machinery, the

Richland resumed a northerly track and re-engaged with the enemy destroyers. One would be crippled by her six and three-inch shellfire before night fell and contact was broken.

Although

Richland was heavily battered, Cascadian forces soon confirmed that she had sunk the

Suma and

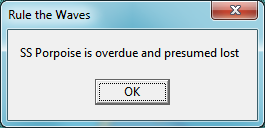

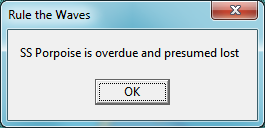

Tachikaze. Presumed lost was the submersible

Porpoise, which had been in the area - a week later the damaged sub limped into Manila Bay, wounded by Japanese depth charges.

By then, it was known that the Battle of the Formosa Straits had been a resounding first blow by the Cascadian Navy, seizing the emotional initiative from the Japanese Navy to start the war.

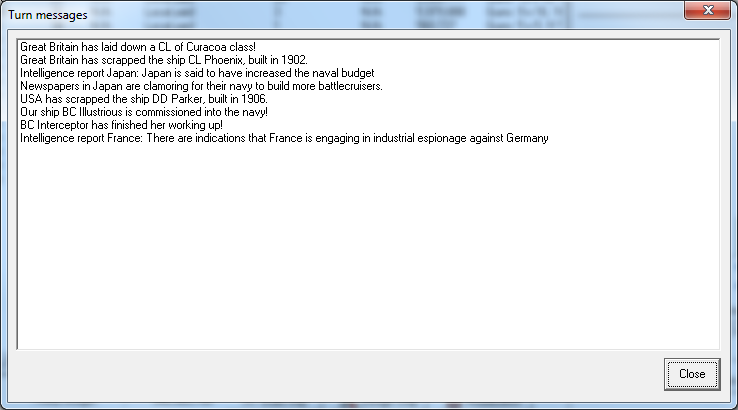

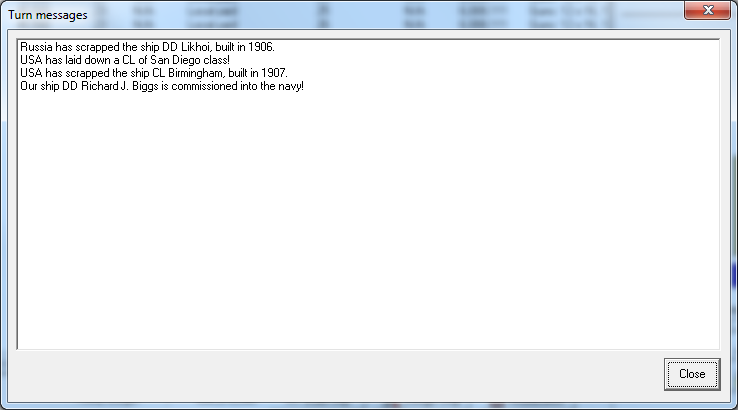

Cascadia received formidable reinforcement within days of the start of the war. On February 17th, the United States of America declared war on the Empire of Japan in compliance with the Second Chicago Treaty.

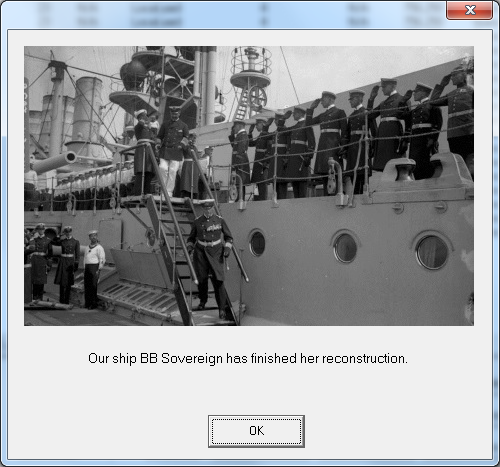

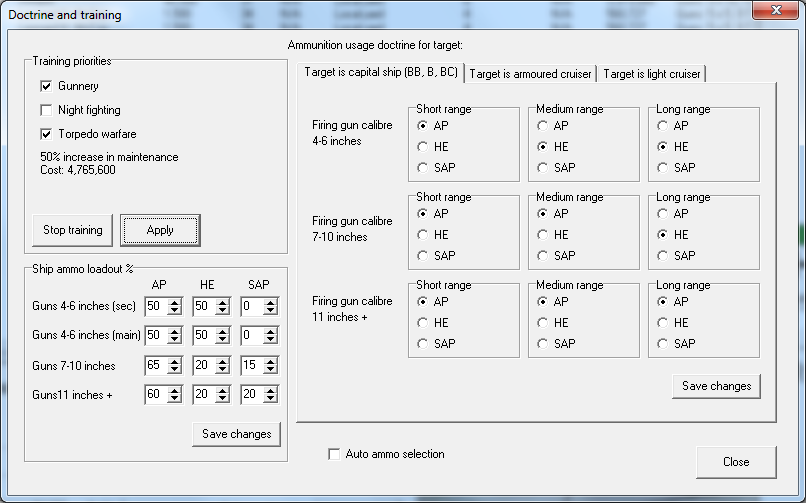

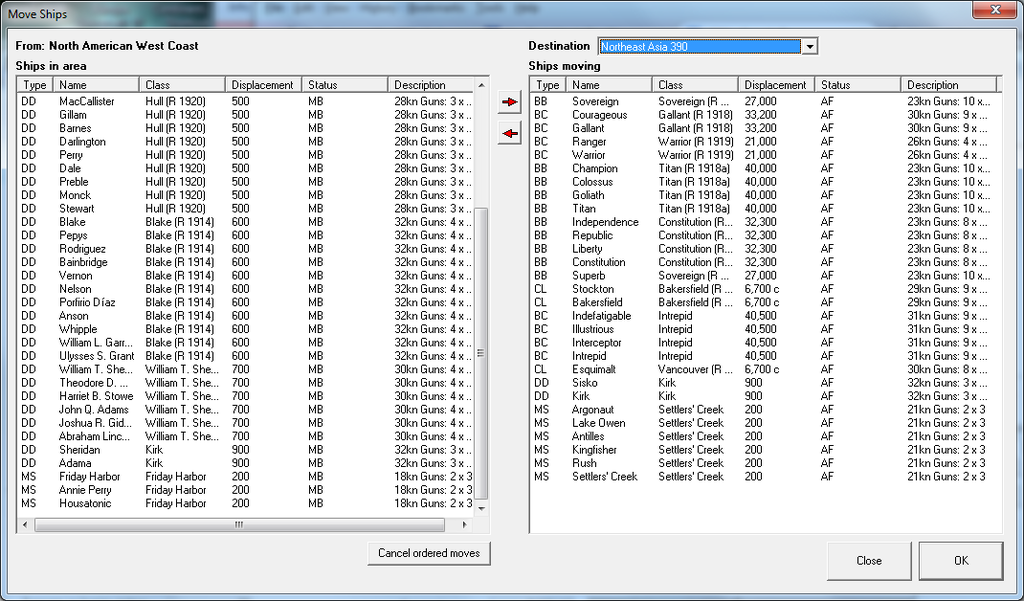

With the war formerly begun, Admiral Garrett restored the funding for enhanced training into artillery firing accuracy and torpedo warfare. A re-deployment of ships was made, with the

Sovereign and

Superb recalled for the moment to Hawai'i to help prevent any Japanese attacks on Cascadia's trans-oceanic supply line. The

Warrior,

Ranger, and the

Pratchett-class destroyers were sent to Manila to support trans-oceanic supply convoys and help secure local naval superiority to begin an invasion of Formosa.

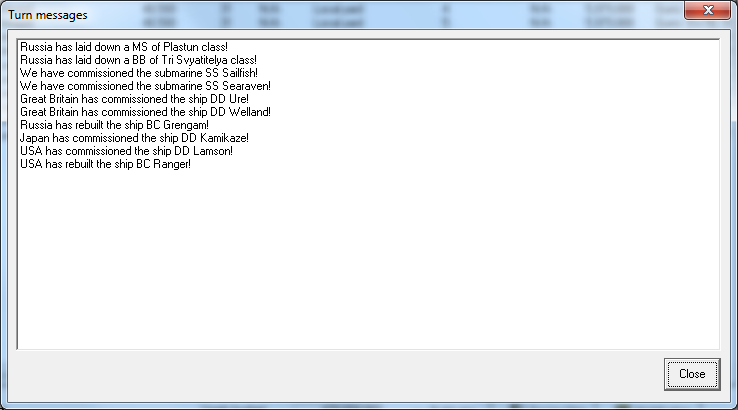

Sovereign Superb sent back to NAWC, Warrior and Ranger and Pratchett DDs sent to SEA

The Japanese sneak attack helped to galvanize popular support. The anti-war movement accused Muniz and Montelbano of manipulating Japan into the attack, an unfair accusation especially for Montelbano who, despite his Hawk inclinations, did desire peace. But for the vast majority of Cascadians, it was a case of a virtual sneak attack by a jealous former ally, and they would flock to the colors to protect their nation. The anti-war movement's marches were damp squibs that had no hope of effecting policy.

Unrest 0

March 1924

The fighting in China continued. A fresh Japanese offensive was thrown at the Cascadian lines; this time, however, the Cascadians were ready for the Japanese infiltrators with special pickets set forward in foxholes, and the infiltration attacks were absorbed by this measure. The Japanese lunged at the Cascadian lines and were bloodily repulsed. Newspapermen would gleefully report to the Cascadian people that the 2nd Guards Regiment had again earned its nickname of "The Iron Wall" from its total repulses of repeated enemy attacks on its sector of the line.

Behind the lines, General Andrew Laffler assumed command of the newly-designated 4th Army, the now-five division force holding the peninsula. "The entirety of the Zone is now one large armed camp," reported a war reporter for the

Seattle Post-Intelligencer. A reporter for the

Times told his English readers of the humanitarian efforts of the Royal Navy, who came in to evacuate civilians from the Peninsula with the blessing of Admiral Wallace and the Cascadian Navy. The East Asia Squadron of the Royal Navy ended up evacuating at least half of the peninsula's population over the following months. For those who remained, rationing and military rule were the order of the day, but so was the money of the Cascadian military for those with the means and wit to provide services for the thousands upon thousands of soldiers, sailors, and officers of the Cascadian defenses.

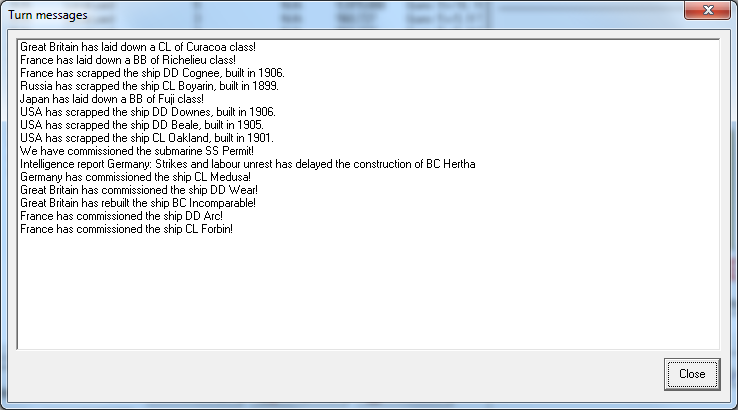

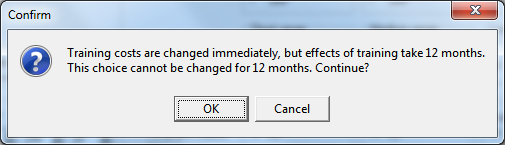

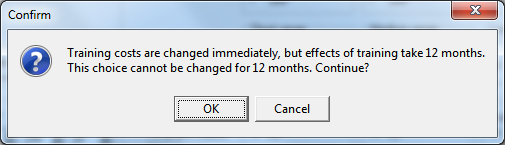

Design experts provide a new refinement to potential torpedo protection systems.

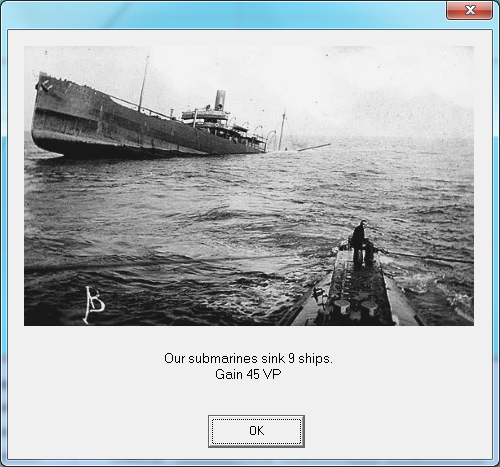

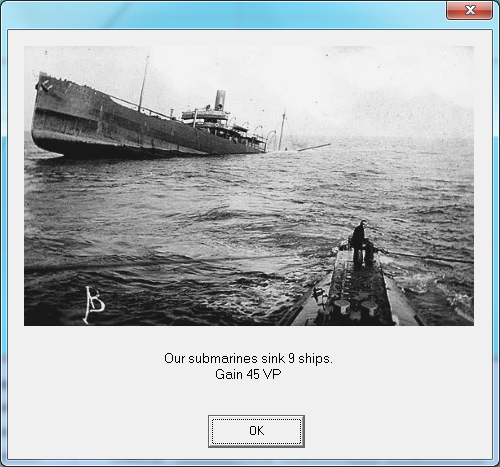

Cascadian submersibles, many operating from Manila and Tsingtao, began their hunt for Japanese shipping in earnest, sinking 10 ships during the course of the month. Only one Japanese sub managed a sinking, of a cargo ship heading toward Hong Kong, after which it was caught and destroyed by Cascadian destroyers in the region.

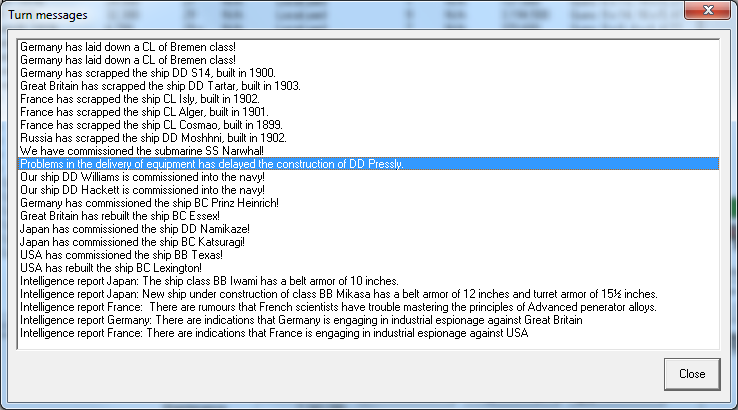

A Japanese mine off Korea sank the

CRS Pressly.

American ships caught a large number of Japanese ships in Caribbean waters.

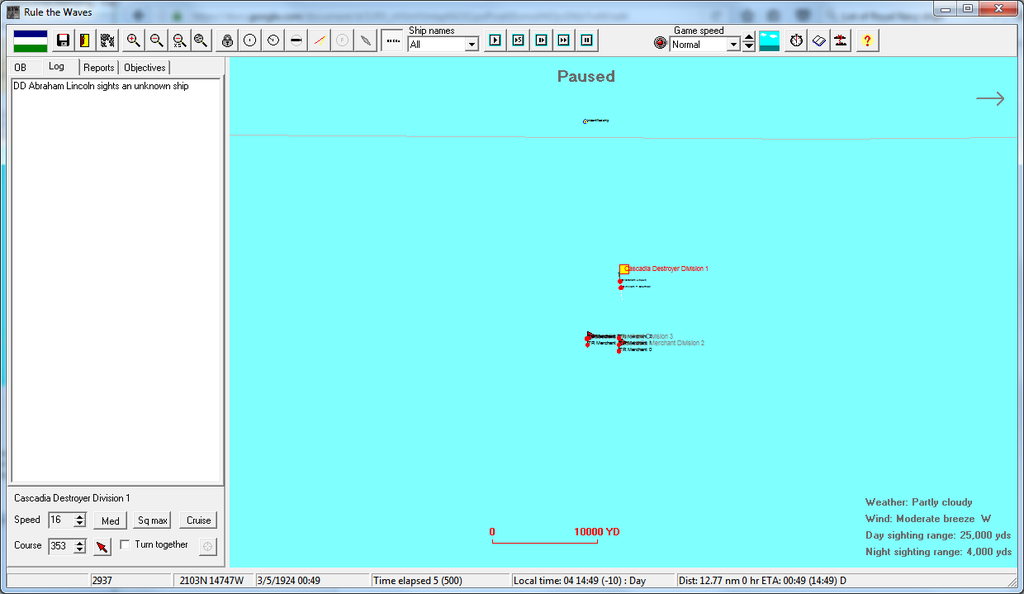

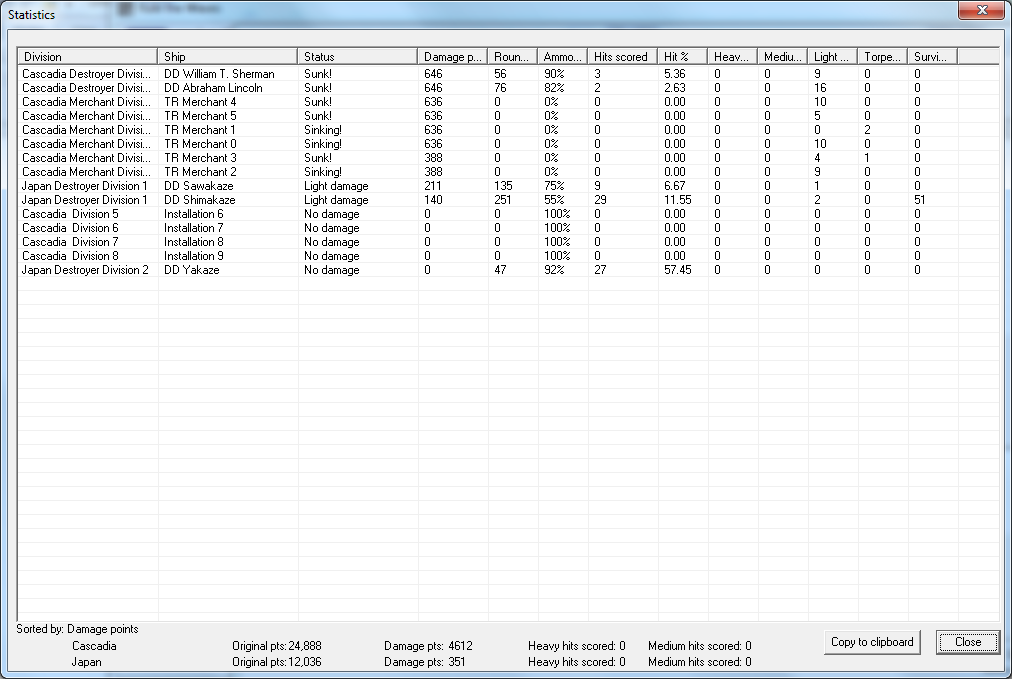

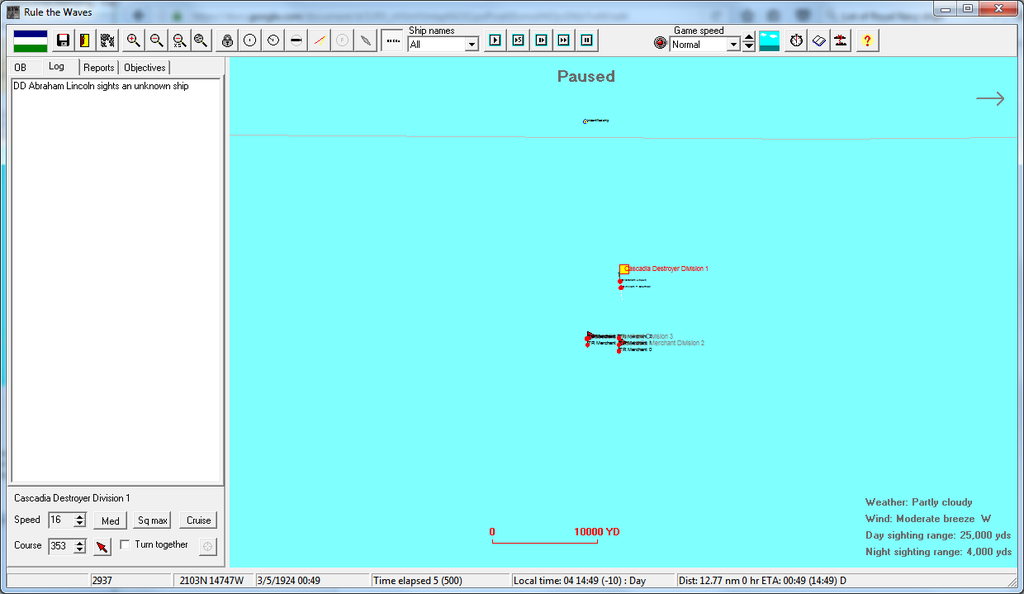

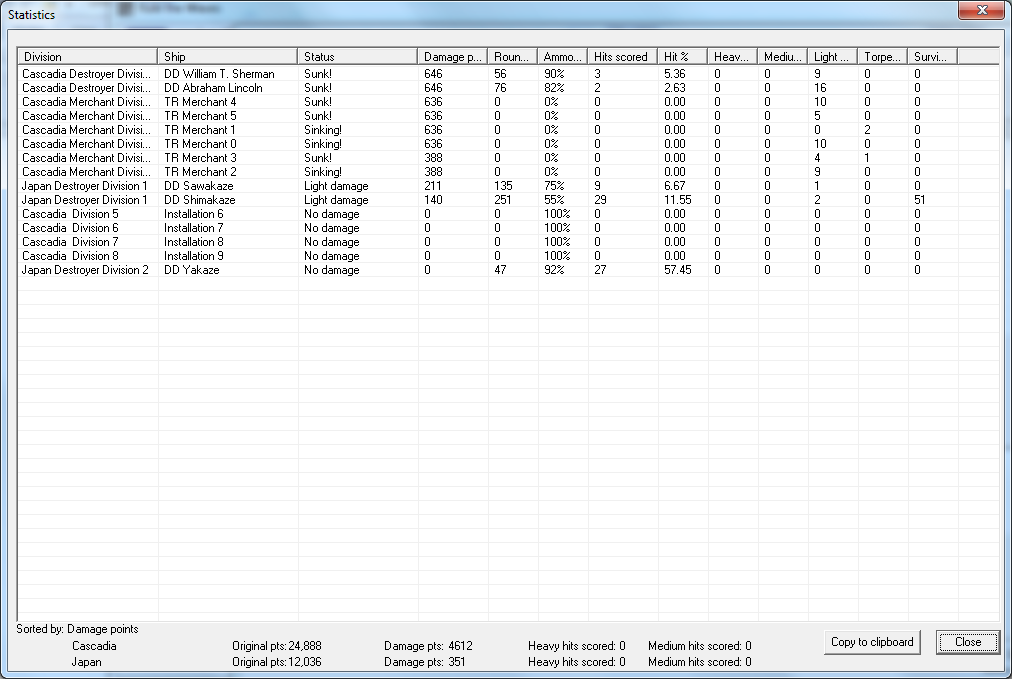

The Japanese made good on the

Richland's raid off Formosa. With the assistance of long-range tenders, the

Yakaze,

Shimakaze, and

Sawakaze raided a merchant convoy designated M2251 being escorted to Hawai'i by the

Abraham Lincoln and

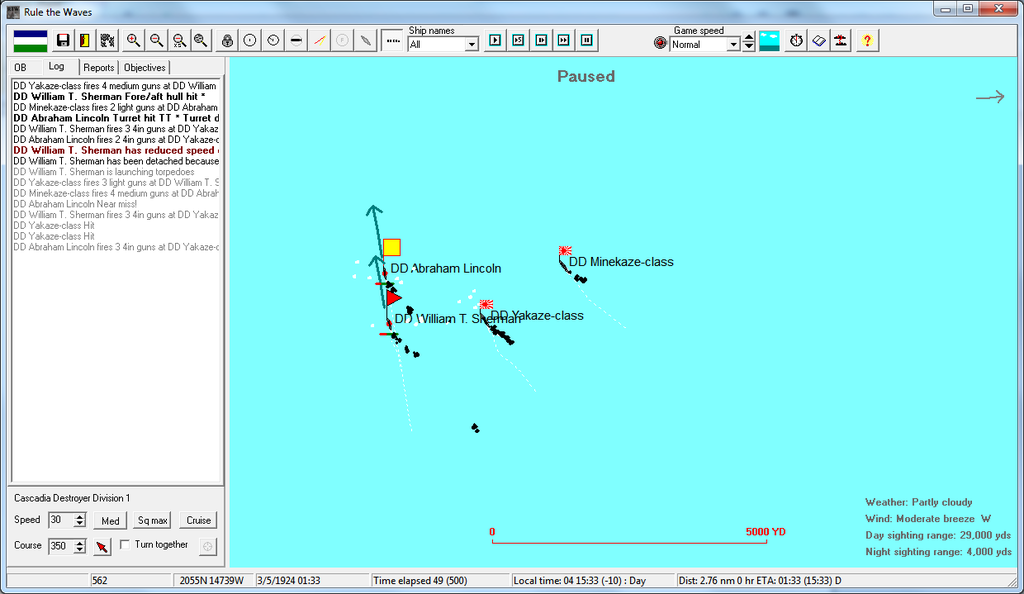

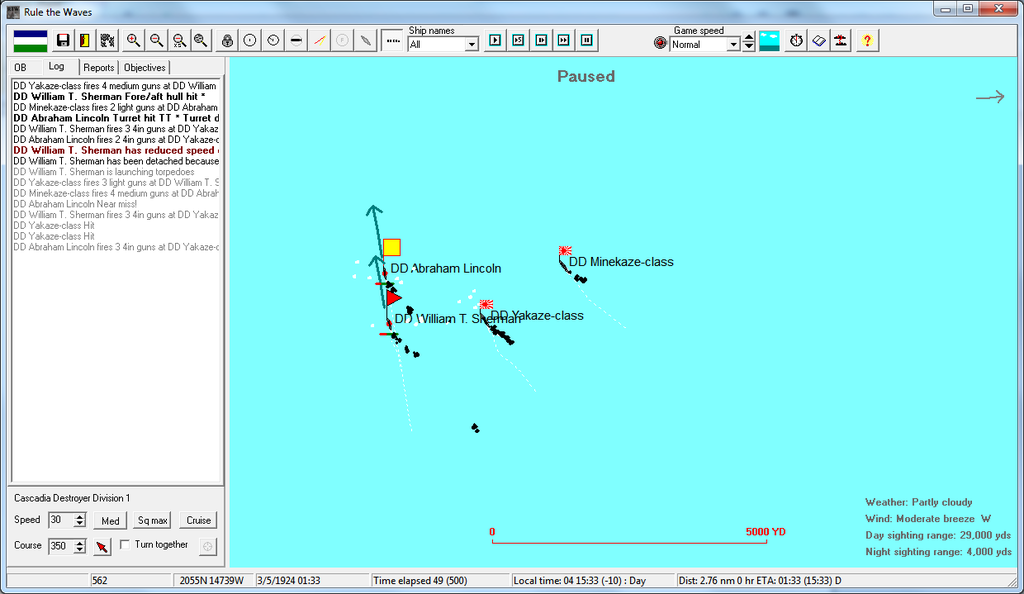

William T. Sherman.

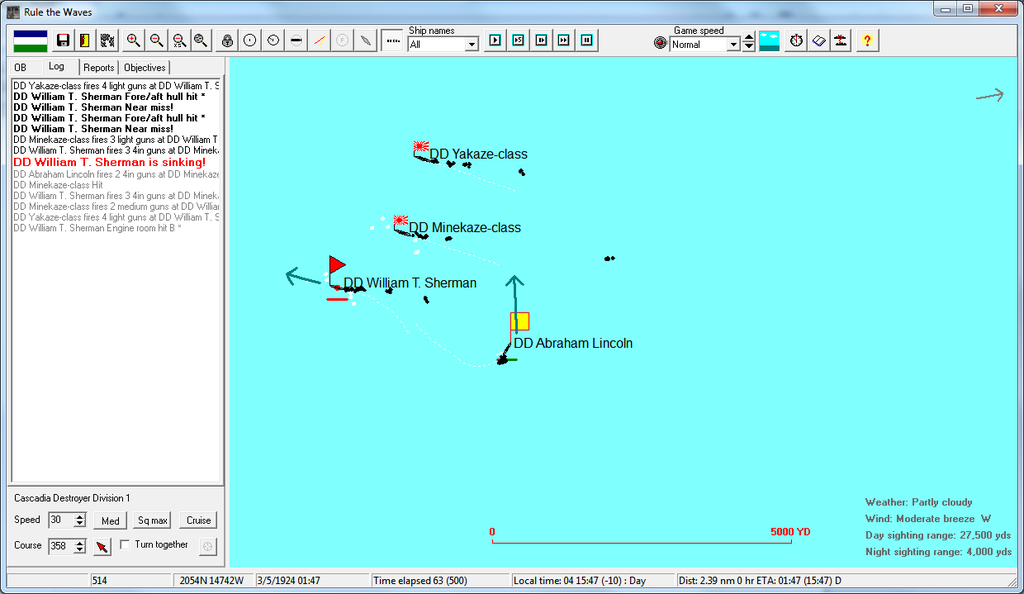

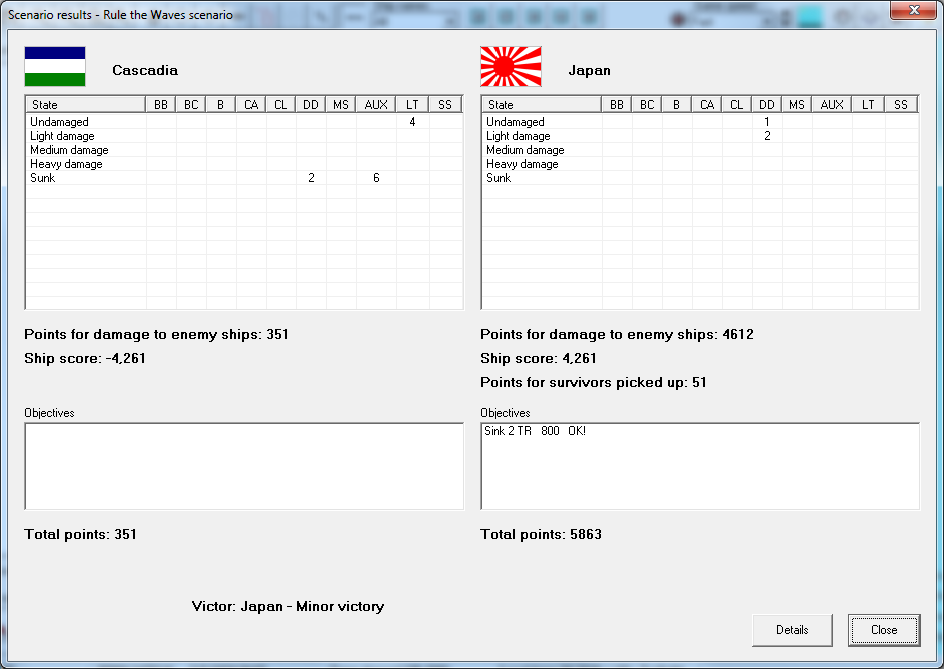

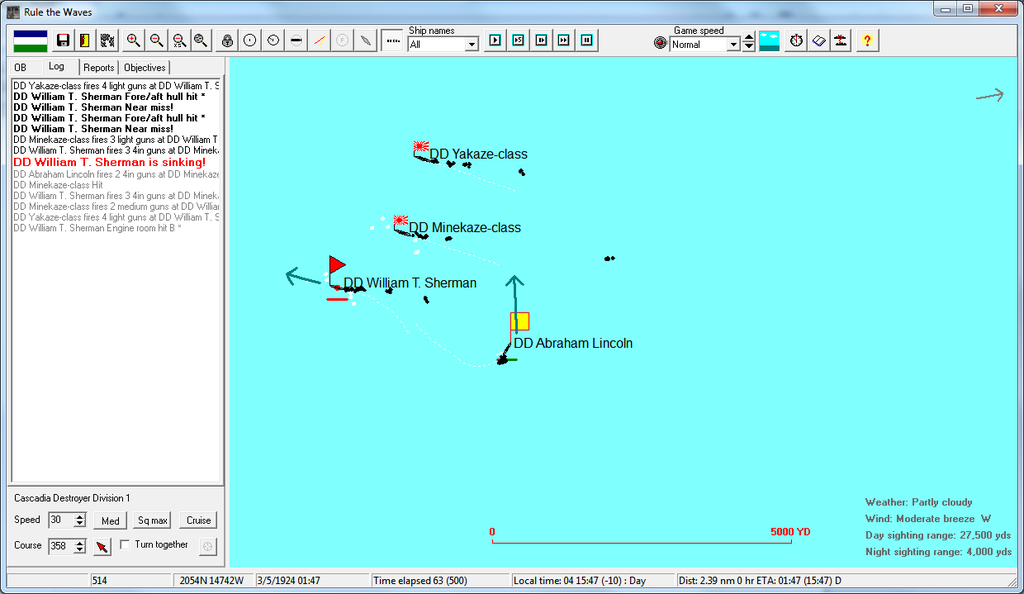

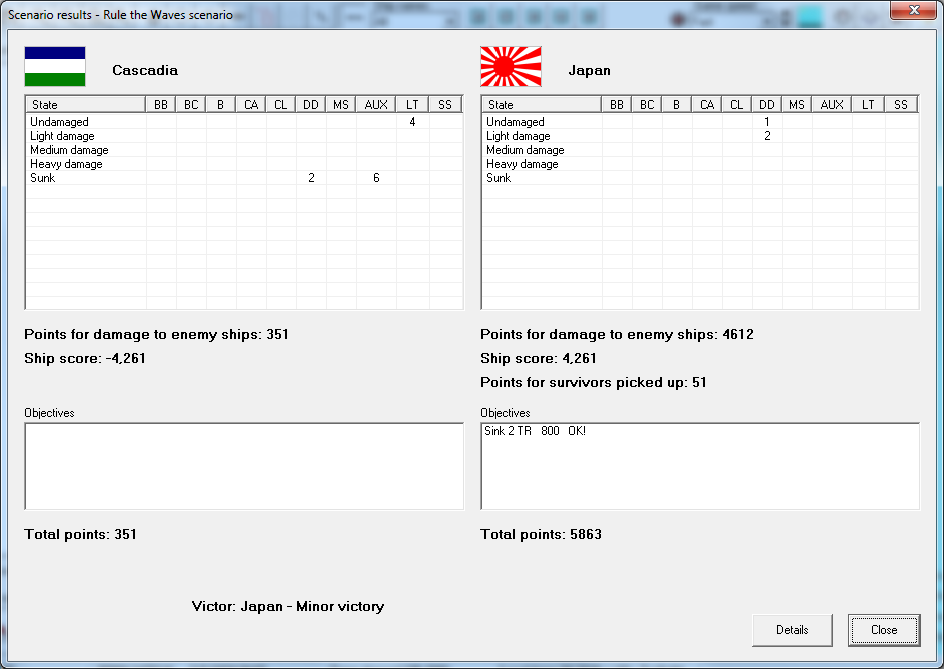

The two Cascadian ships were 700-tonners, their three Japanese adversaries 1,500-tonners, and the size difference doomed the convoy. Within an hour of the battle being started, the

Sherman was sinking from the effects of the Japanese gunfire.

Lincoln went down over forty minutes later. With the escorts annihilated, the Japanese hunted down the six merchant ships and sank them all.

The disaster was an embarrassment to the Cascadian Navy. Dove politicians used this as grist in their Opposition arguments, declaring the Admiralty's policies to be the cause of the attack due to their emphasis on building capital ships and not completely replacing the older destroyer fleet.

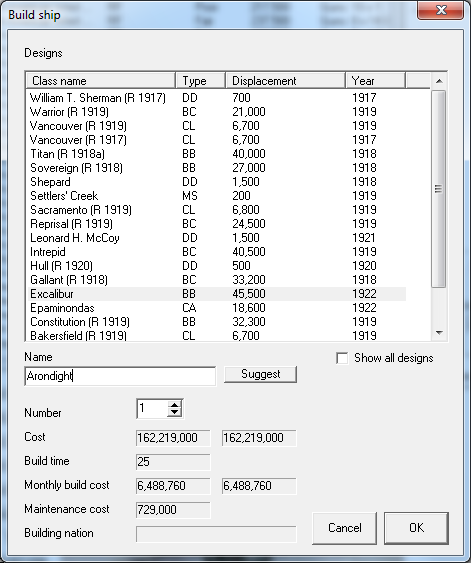

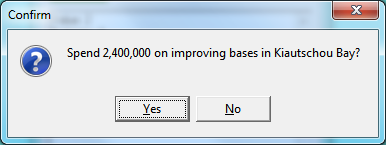

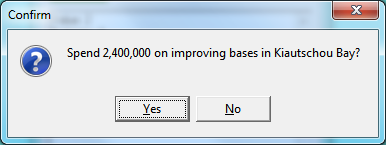

With the need to support a blockade fleet, the Navy ordered expansion of the base facilities at Tsingtao. The costs incurred meant that even with the impending war budget, the work on the

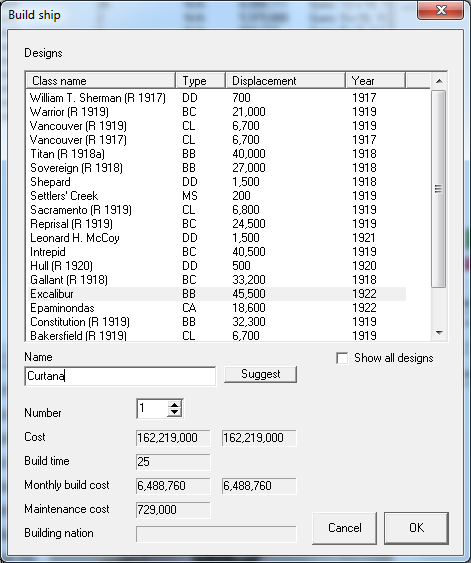

Arondight and

Curtana had to be suspended.

The Navy shifted more vessels around in response to the Japanese attack on Convoy M2251.

April 1924

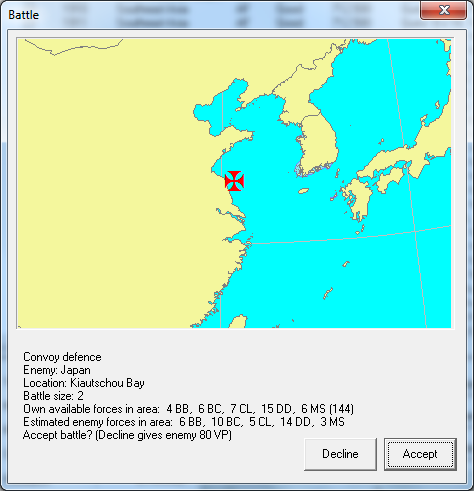

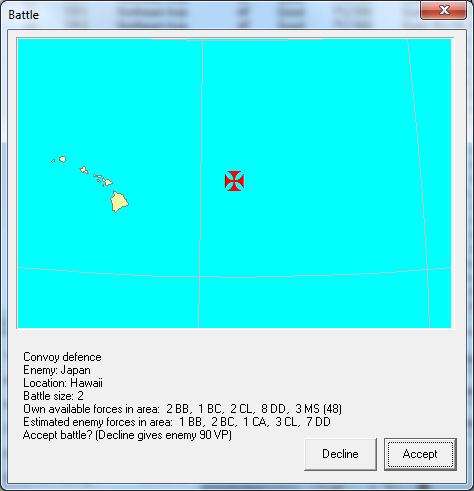

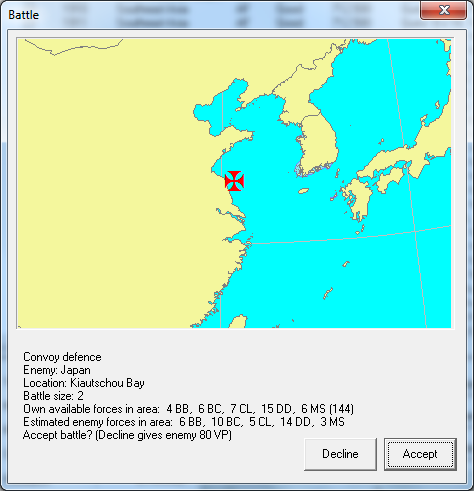

The Cascadian-Japanese fighting remained in stalemate. Cascadia was still trying to secure her supply lines to Dalien and Port Arthur - no offensive to drive the Japanese away could be mounted until the Japanese fleet had been driven back from the shipping lanes.

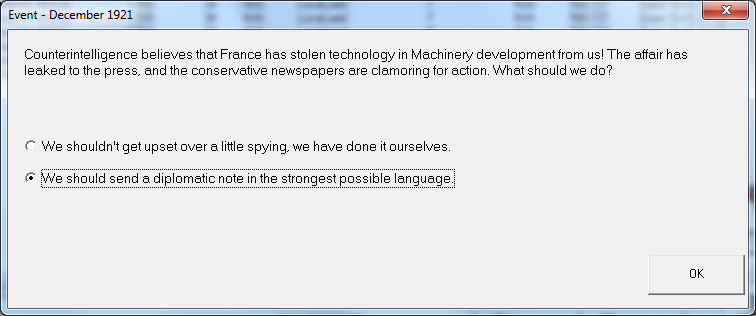

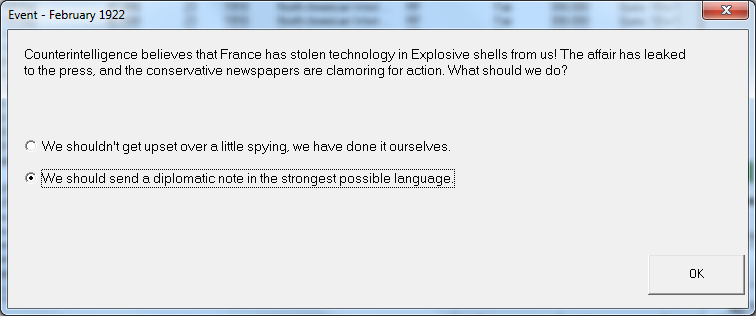

German agents were accused of stealing plans for Cascadian HE shells. The Cascadian government protested this action.

The Japanese submersibles were more active in the month, sinking four Cascadian ships in the Yellow Sea. But they fell far behind the Cascadian count, with Cascadian subs sinking 9. Additionally the

Apache and

Navajo each sank a Japanese ship off the Chinese coast. Fresh from Manila repair yards,

Richland caught a Japanese tanker leaving Balikpapan and sank her.

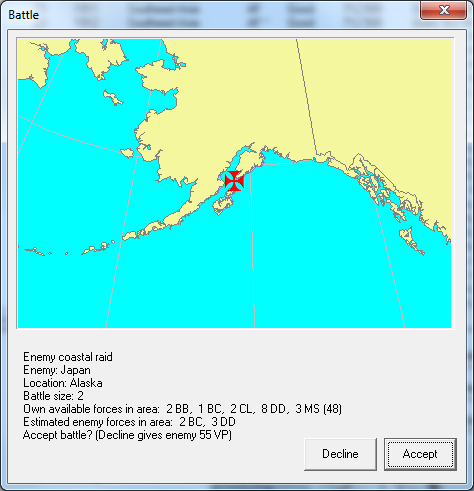

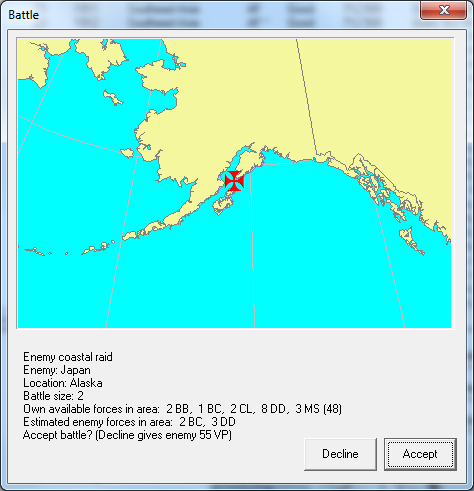

Japanese plans to raid off Alaska were called off.

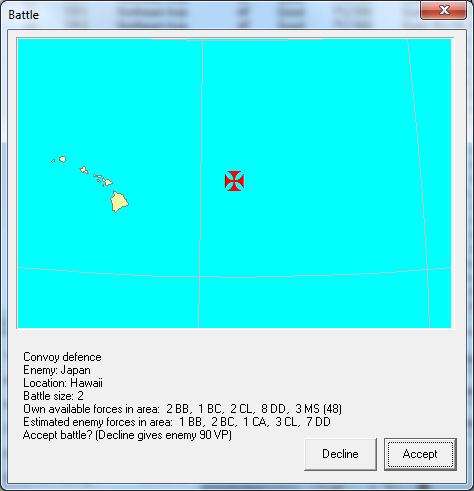

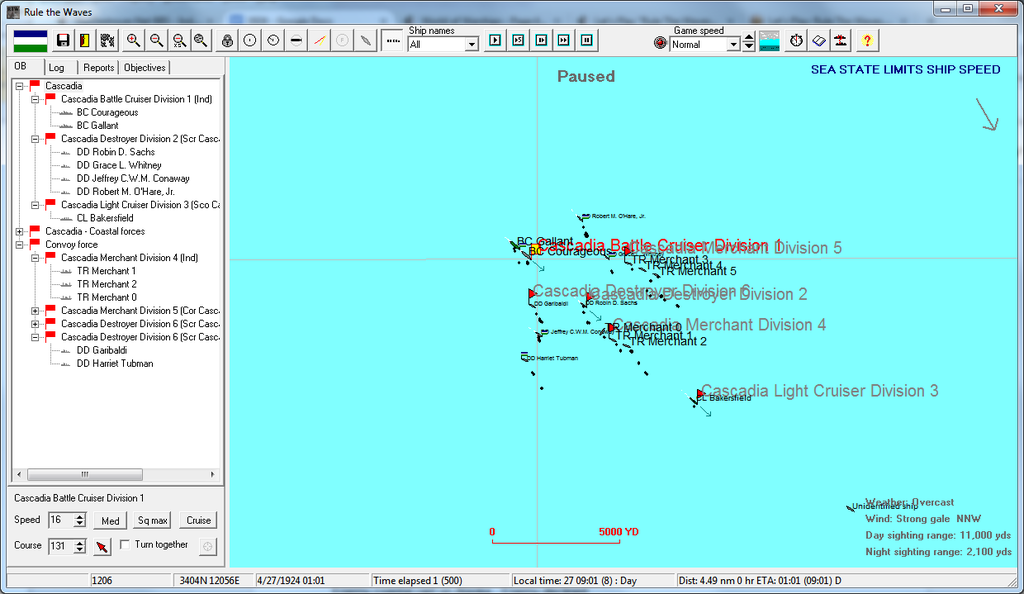

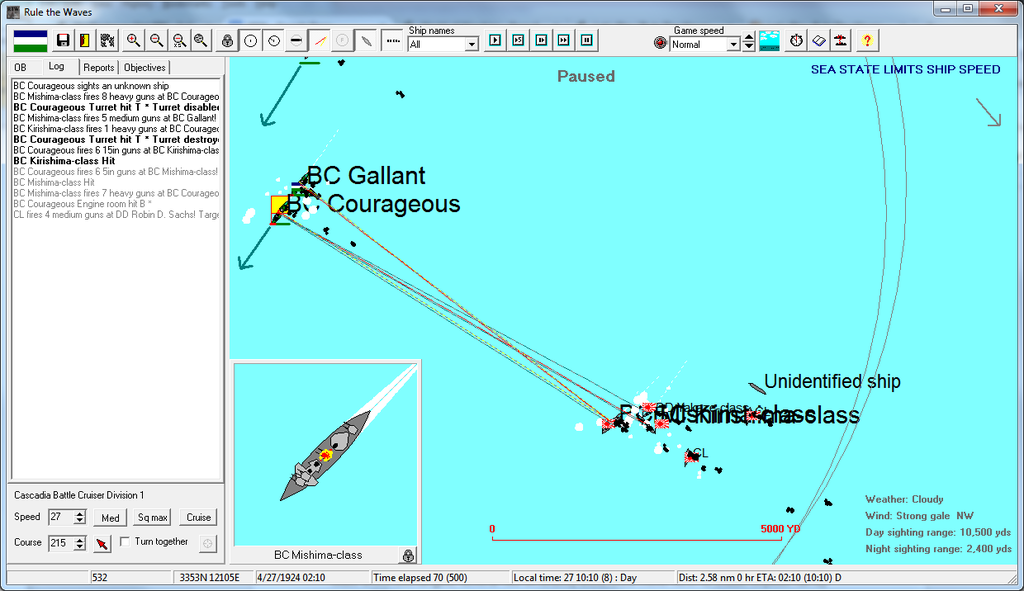

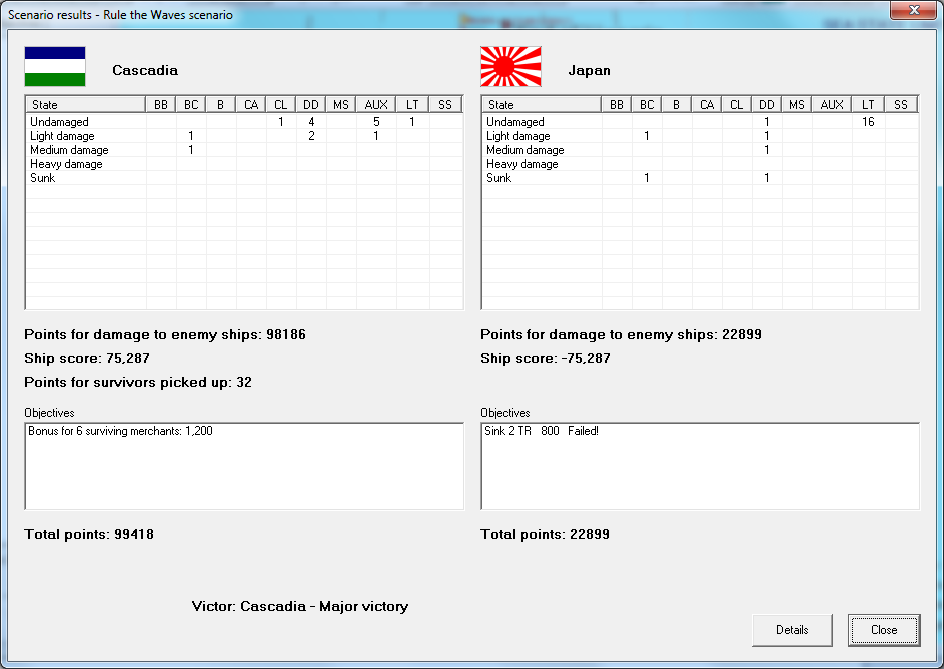

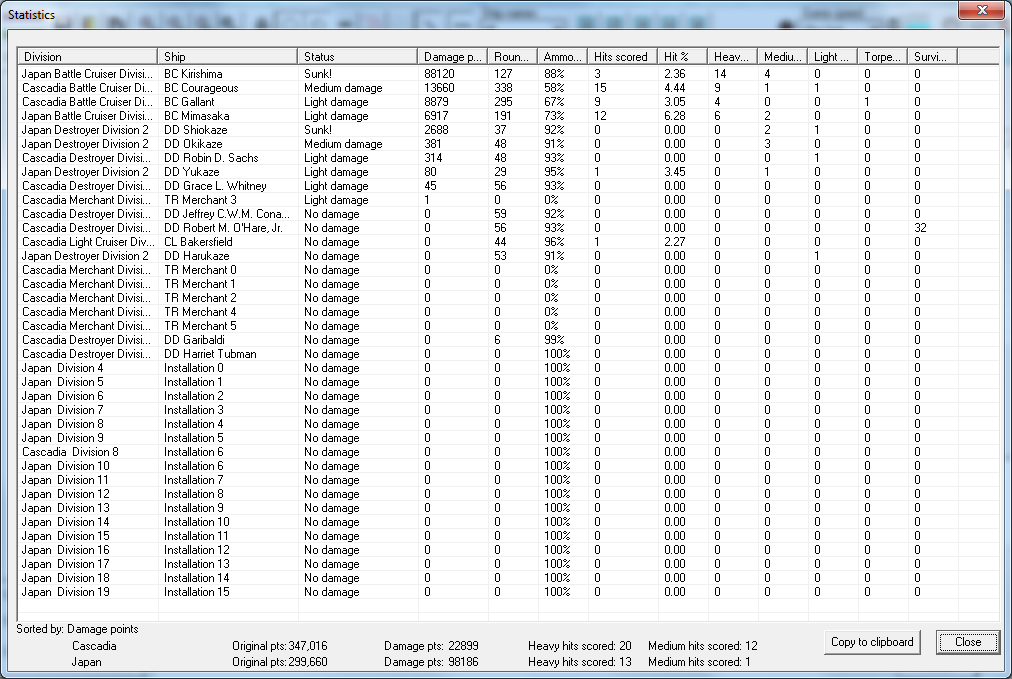

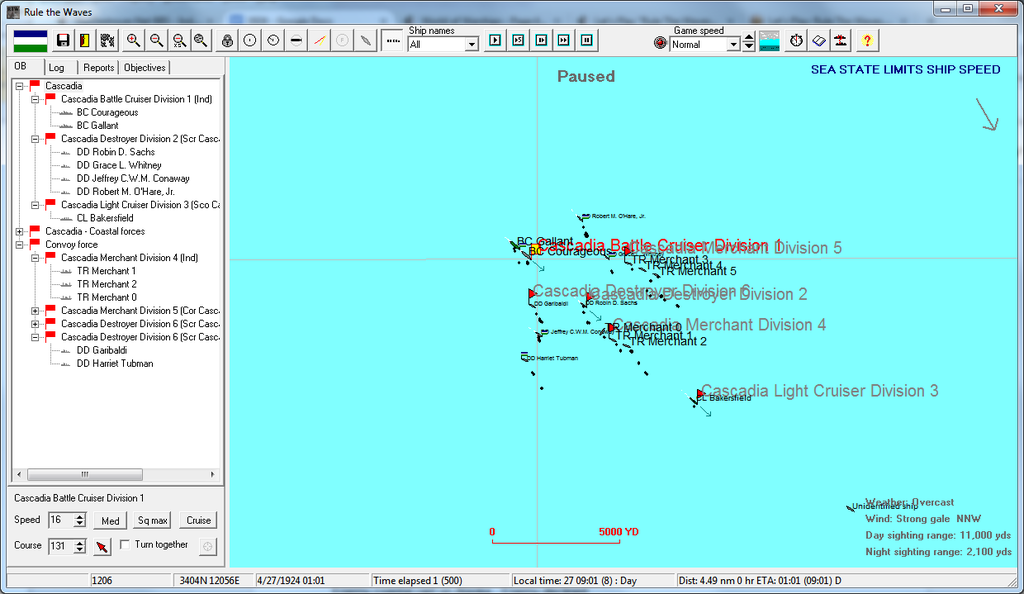

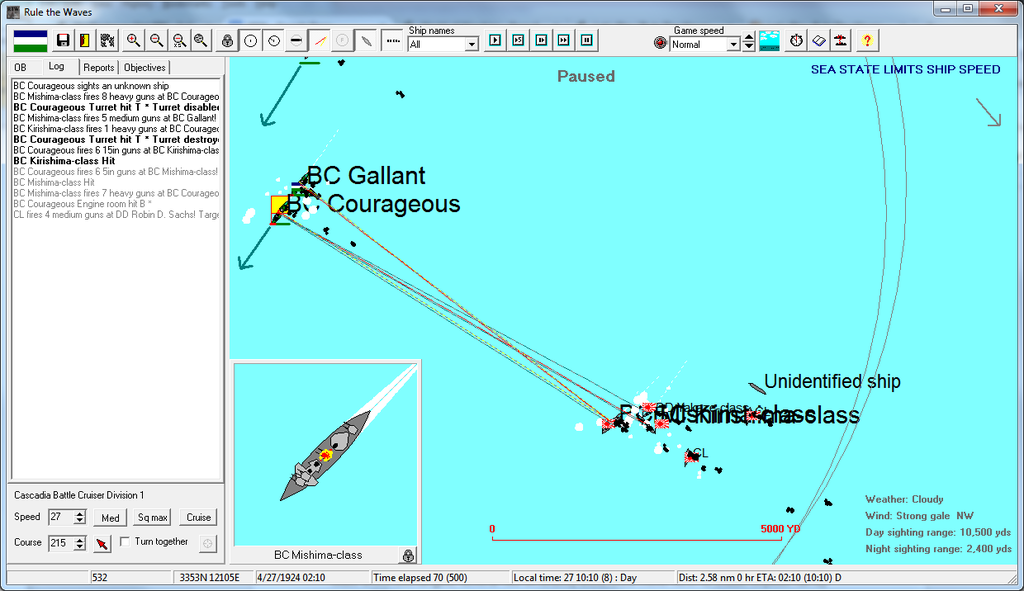

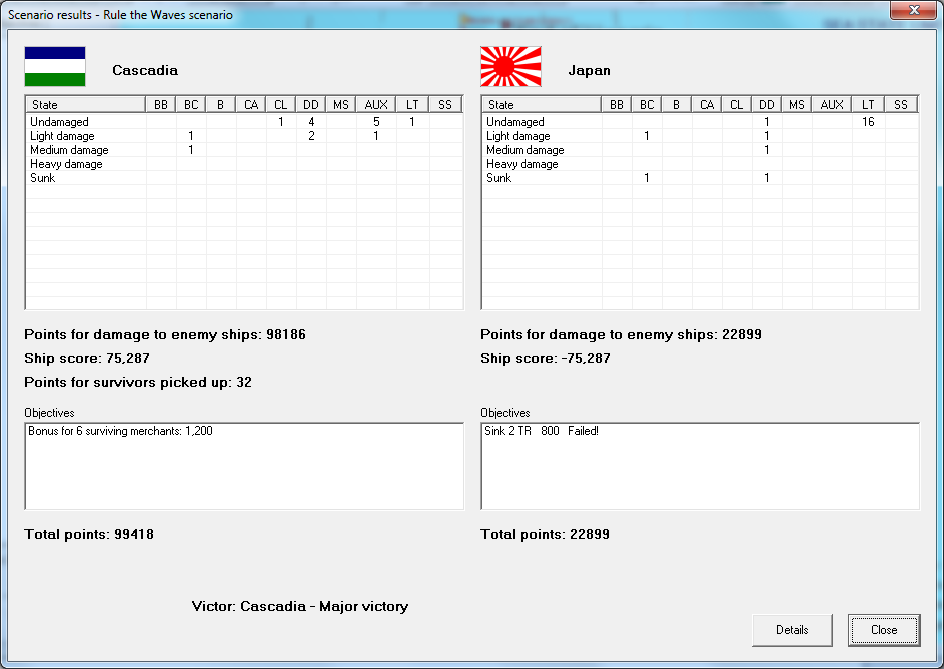

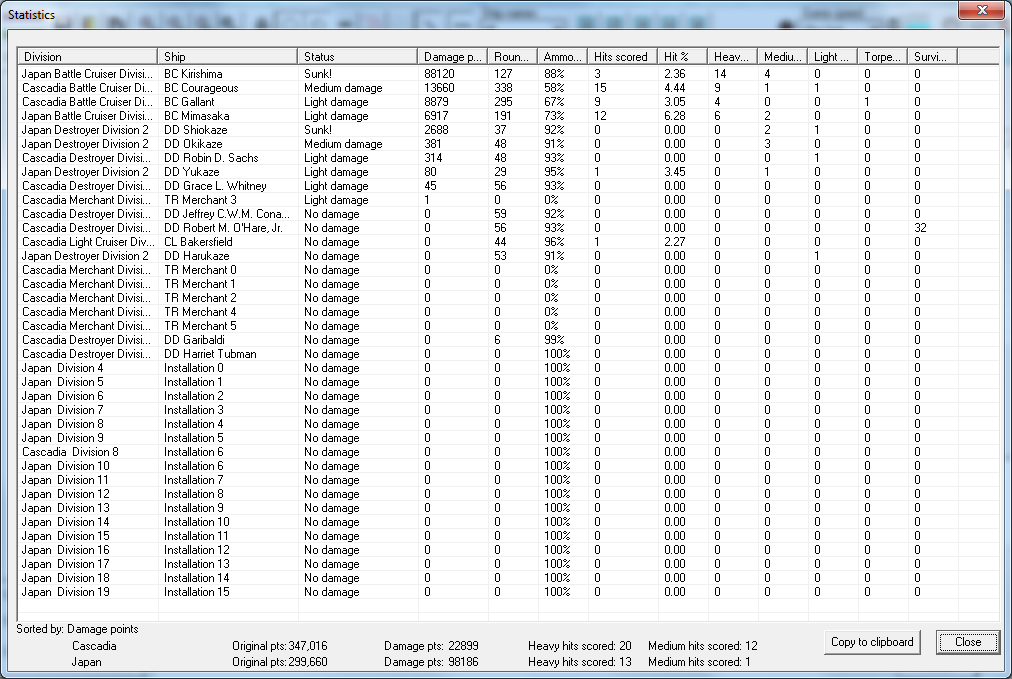

Near the end of the month, on the 27th, the Japanese battlecruisers

Kirishima and

Mimasaka led a squadron of four destroyers to raid a Cascadian convoy detected by Japanese submersibles as it neared Tsingtao.

CRS Courageous

CRS Courageous

Near 34.04N 120.56E off the Chinese Coast

27 April 1924

The ships of the 2nd Battle Scout Squadron, 1st Division, steamed their way past the merchant ships steaming for Tsingtao as part of convoy TS-4. On the flag bridge of the ship, Rear Admiral Lawton Smythe swept the seas with his binoculars. The skies were overcast and the exhaust smoke from his ships was spraying out far, courtesy of the strong gale winds howling from the northwest. The

Courageous and her sister ship, the

Gallant, moved forward accompanied by four destroyers of the new

McCoy-class. Far head, the veteran scout cruiser

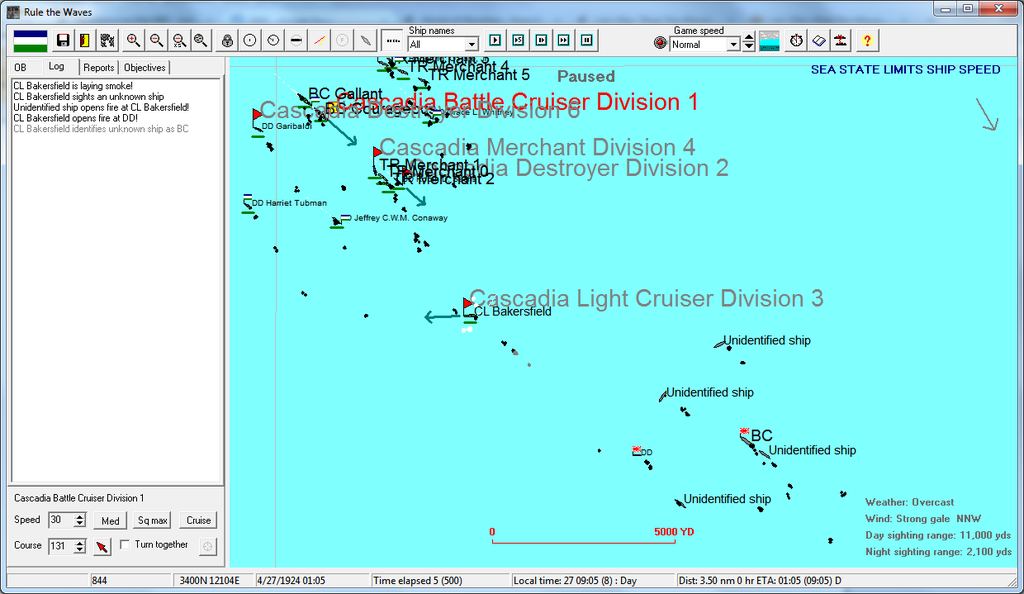

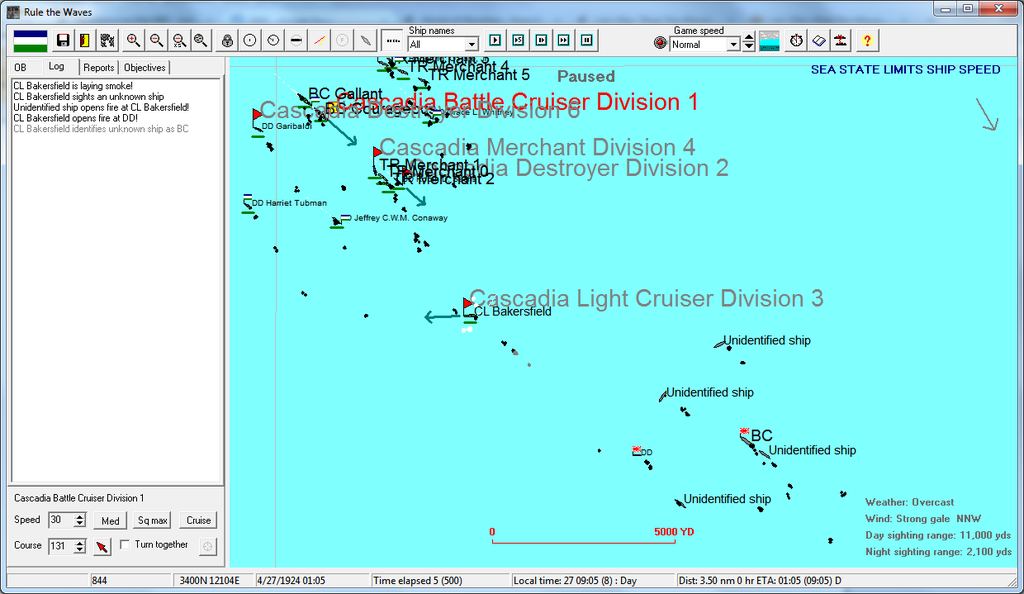

Bakersfield had moved past the convoy and signaled the awaited signal: "Enemy vessel sighted."

On the command bridge Captain Joshua Rogers was already giving the order, and the wail of the klaxons and the voice of one of Rogers' officers summoned the crew of the battlecruiser to their battle stations.

The ships charged to the southeast, speeding to flank speed to intercept the enemy before they could fire at the slow, helpless convoy. The

Bakersfield continued to signal the believed identities of their foes. Soon the word came: "Enemy battlecruisers spotted."

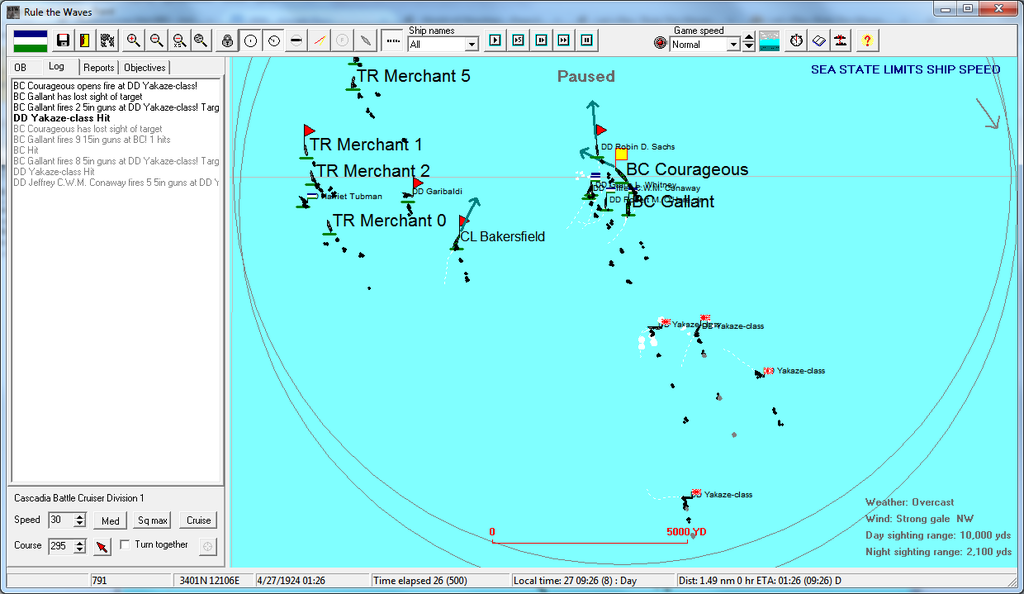

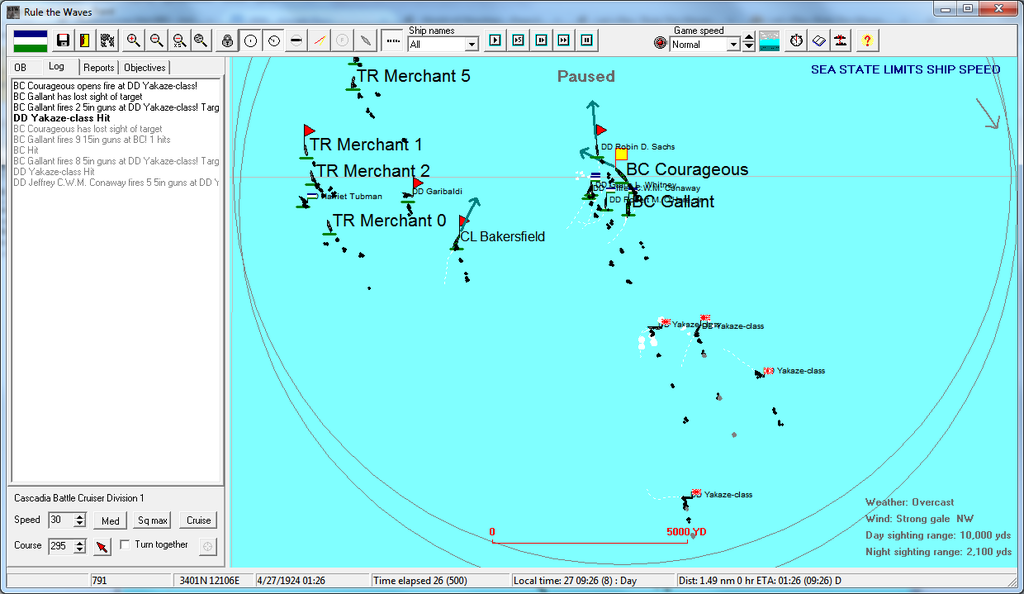

At 0925 local, the 15" guns on the

Courageous thundered. In the distance there was indication of a hit. Within a minute it looked like another hit had taken them in the superstructure. A potential bridge hit? Smythe couldn't see.

Ahead more signals came from the other ships, and Smythe himself saw the Japanese destroyers moving toward them. "Signal to bridge and to

Gallant, turn to port. We need to keep them from getting in a torpedo run."

"Aye sir."

The secondary and primary guns on the

Courageous continued to thunder. One shot from their five inchers landed a hit on an enemy destroyer. The enemy destroyers, facing the fire of the Cascadian ships, moved close enough to fire torpedoes before falling back on

Kirishima and

Mimasaka. Smythe let Rogers and Captain Obregon on the

Gallant take charge for evasive maneuvers to avoid the torpedoes. "Port again. Bring us back on the enemy battlecruisers."

With this maneuver complete, the fire between the two sides picked up. Smythe swallowed and focused on holding the sea's spaces in his head. The convoy needed to be covered until it was safely away. And if Smythe could take out an enemy battlecruiser…

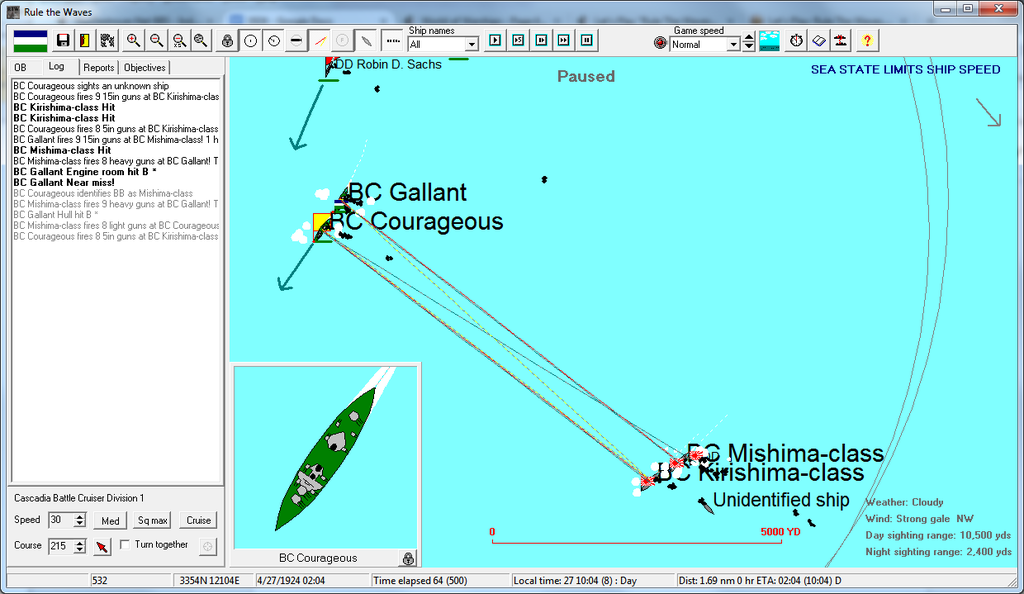

Now the two duos lined up and started battering each other, the battle being truly joined at the top of the hours. Smythe felt his blood rush. For the first time in six years, the Cascadian Battle Fleet was engaged with an enemy. And the stakes were Cascadia's empire in East Asia.

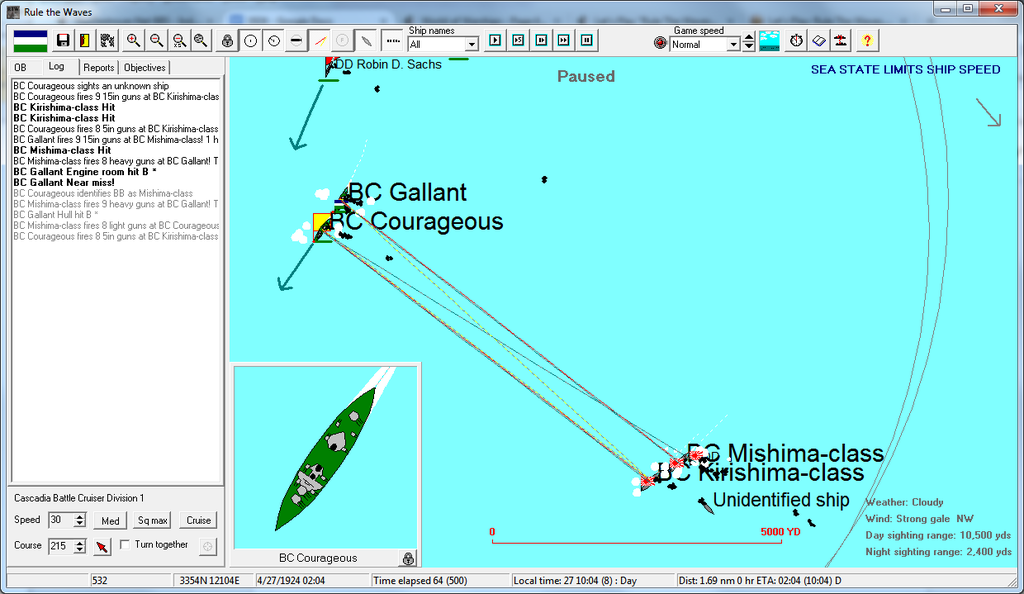

Dark puffs on the profiles of the enemy vessels were evidence of the incoming fire, even as the 15"-inchers on the

Courageous thundered their fury yet again, a fury that made the deck shake. Shells rained down around both sides. Their respective gunners had a formidable task, trying to track and accurately hit enemy battlecruisers capable of speeds above twenty-five knots.

And both sides were delivering hits. Smythe saw evidence of the hits on the enemy, particularly the one with the outline of the

Kirishima. Meanwhile

Gallant signaled she had a fire just after 1004.

Minutes passed. A thunderous blast tore through Smythe's concentration. "We just lost the aft turret!", one of the officers shouted.

Damn. Three guns out of commission. That gave the enemy a possible advantage.

An advantage that was quickly shown to not be decisive. The

Kirishima was clearly starting to fall out of line. Her hits were severe, her drives were failing. And still the fire continued.

For Smythe, time almost lost meaning. There was only the cloudy sky and the murky sea, agitated by the increasing wind. Shells were fired, shells rained down on them, and some found their mark. Both Cascadian ships were taking damage, but he had the position of being able to finish off the

Kirishima.

Then, into the battle's second hour, the Japanese destroyers darted forward again. A spout of fire and a ferocious blast geysered beside

Gallant. The Cascadian battlecruiser had taken a torpedo hit. It would, give the protection built into it, not be immediately endangered. But it would definitely require caution from

Gallant on her activities.

The Japanese may have felt a morale boost from the torpedo hit. If it did, it was lost two minutes later. A shell from either

Courageous or

Gallant struck

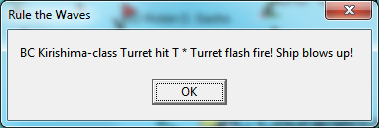

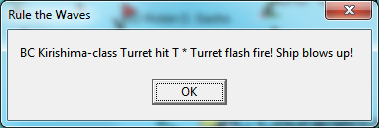

Kirishima in the turret.

There was as massive fireball that engulfed the Japanese ship. Smythe, nobody, would ever see

Kirishima again.

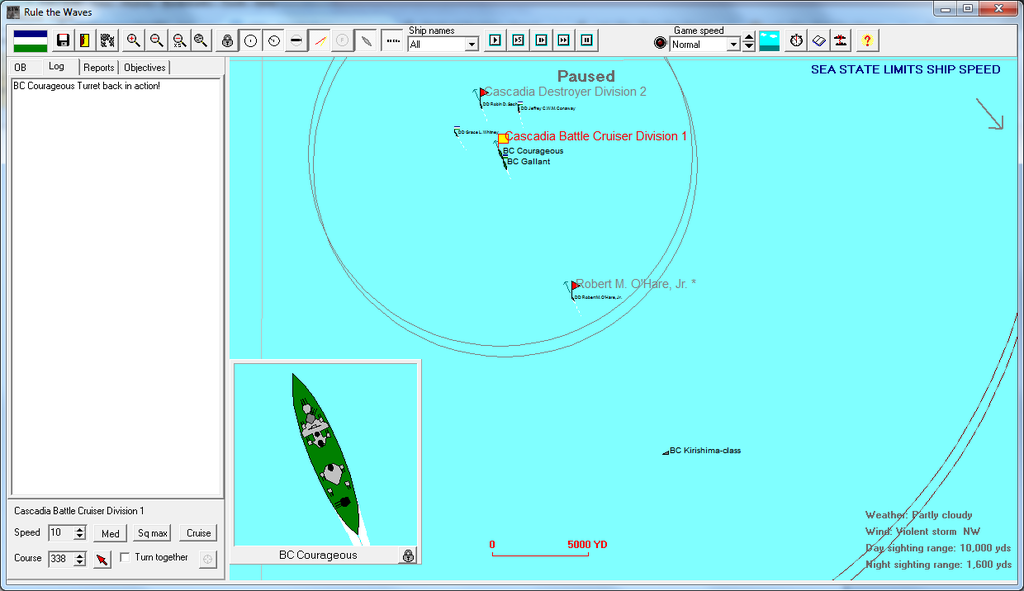

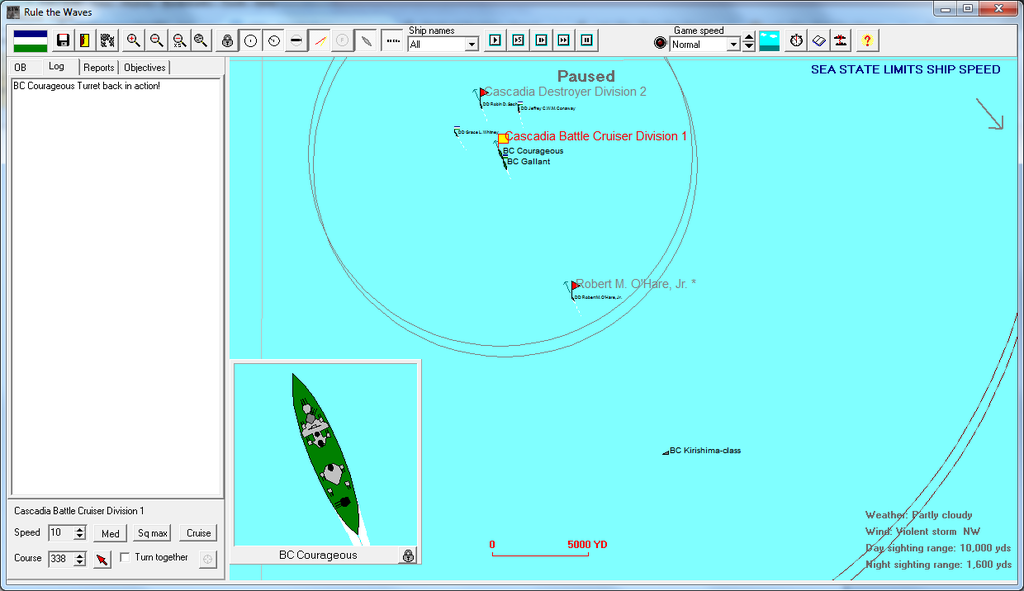

The loss of the

Kirishima took the fight out of the enemy. The other vessel broke away steadily to the south, exchanging shots with the two victorious Cascadian ships until it was safely away. The

O'Hare was detailed to find survivors of the

Kirishima and the rest of the force turned north to meet up with the convoy.

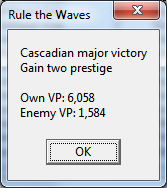

The battle, with the loss of one Japanese battlecruiser and, Smythe would later learn, a Japanese destroyer, was just the thing to take away the sting of what happened to Convoy M2251. The victory was lauded in newspapers. Smythe and his superiors, including Admiral Garrett, could consider the victory a vindication for the Admiralty's policies.

The Navy funded further base improvement work in Sumatra, Kamchatka, and the Liaotung peninsula.

The new war budget led to three more submersibles being ordered.

May 1924

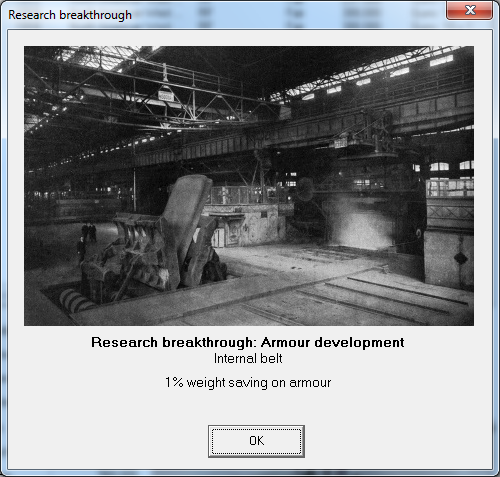

Naval armoring experts reported progress in formulating a specialized decapping belt for warship armor.

An unanticipated flash of genius led to advanced weight saving methods being found before planners thought they would ever achieve it.

The Cascadian submersibles were still leading the commerce war, claiming another strong month with ten Japanese merchant ships sunk. The cost was two lost submersibles from Japanese countermeasures.

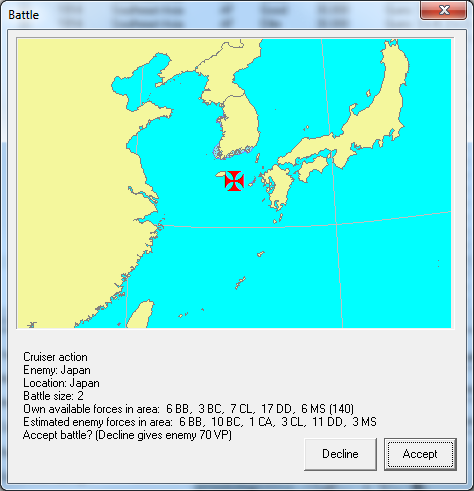

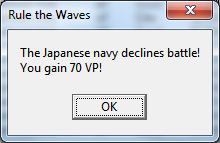

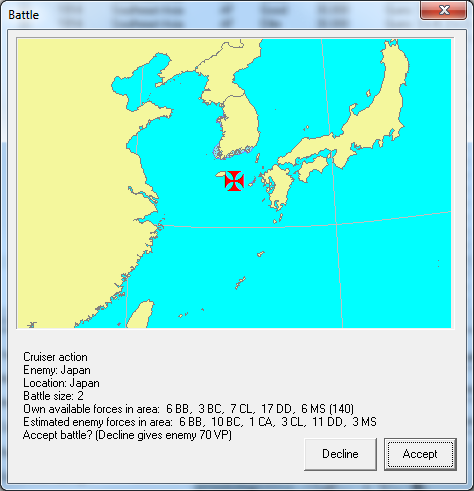

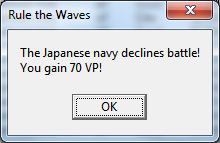

Japanese cruisers refused to engage a Cascadian force off Jeju Island, south of Korea.

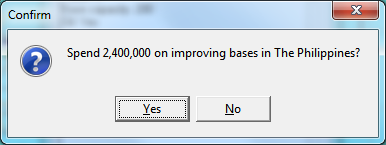

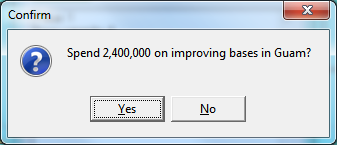

The base expansion orders continued, with new fleet facilities ordered for Guam and Manila Bay. The latter met with perfunctory permission from the Republic of the Philippines, which declared war on Japan on May 4th following the sinking of a Philippine-flagged vessel north of Luzon by a Japanese submersible operating under cruiser rules. The Japanese charged that the Filipino vessel had been carrying food to the Cascadian garrison at Liaotung.

June 1924

June 1924

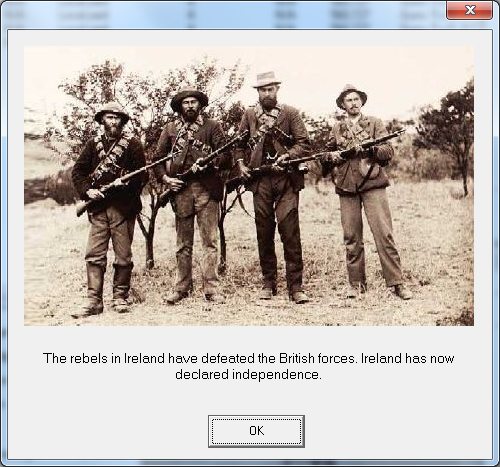

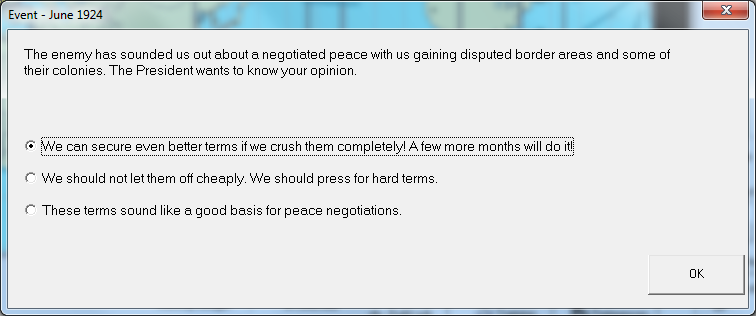

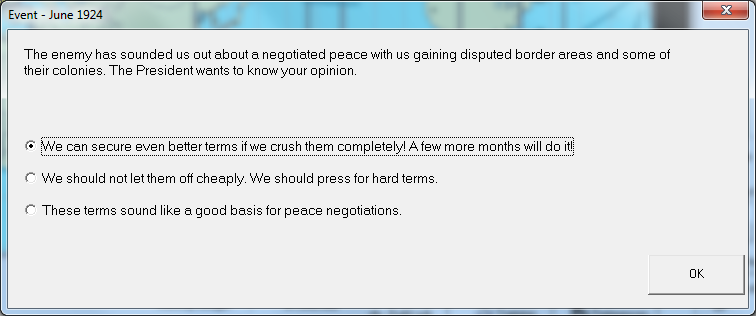

The militarists in Tokyo were outmaneuvered by the peace faction, who foresaw that defeat of Japan at the hands of a roused Cascadia backed by the industry and wealth of the United States. Japanese officials forwarded a peace offer to the Cascadian government through the British, offering concessions in Manchuria and reparations in exchange for peace.

The Cascadians, however, were in no mood to make peace on light terms. Anger over what many saw as the treachery of a former ally fueled the Hawks' popularity. Montelbano and Muniz contemplated the offer, but it was insufficient for the mood of the country. The counter-offer would make the Japanese recoil in disgust: they would be forced to cede Formosa to Cascadian control and withdraw militarily from Manchuria. It was the kind of terms that could only be understood if Cascadia had shattered Japan's strength. It had not done so. The Japanese, understandably, refused the peace offer and resolved to fight on.

Armoring experts finished testing to prove the worthiness of new decapping belts for ship armor. Meanwhile officers from Naval Ordnance reported to the Chief of Naval Design and Procurement that they were ready to place orders for new superheavy shells to be used as AP rounds.

Cascadia's submersible warfare continued unabated, with another 8 Japanese ships sunk in the month at the cost of another Cascadian sub.

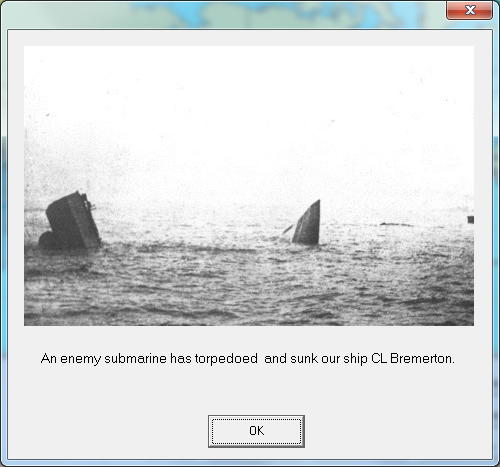

But this time the Japanese also won a key victory: a Japanese submersible on long-range patrol torpedoed and sank

CRS Bremerton northwest of Samoa. Captain Lawler and much of his crew went down with their ship, including the trophy she had won for her victory in the prior year's shooting competition. Four Cascadian merchant vessels also went down to the Japanese torpedoes, and the armored cruiser

Kinugasa began a long reign of terror in the waters between Hawai'i and the North American West Coast by sinking a lone Cascadian cargo vessel.

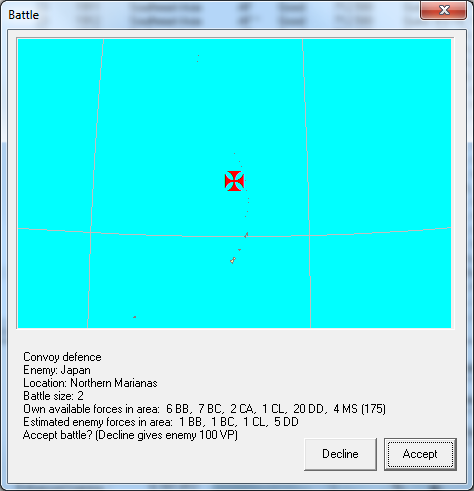

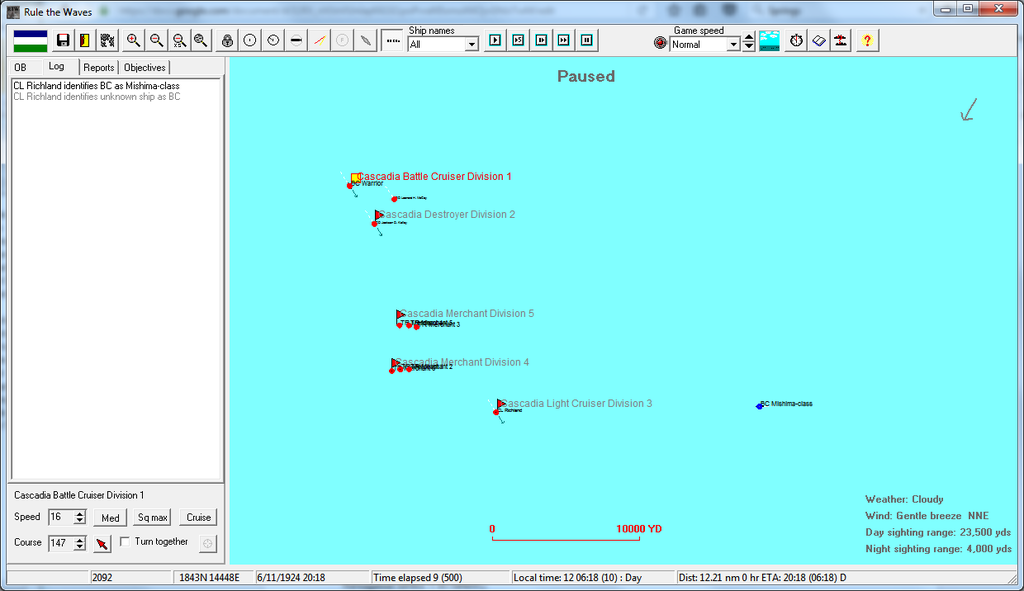

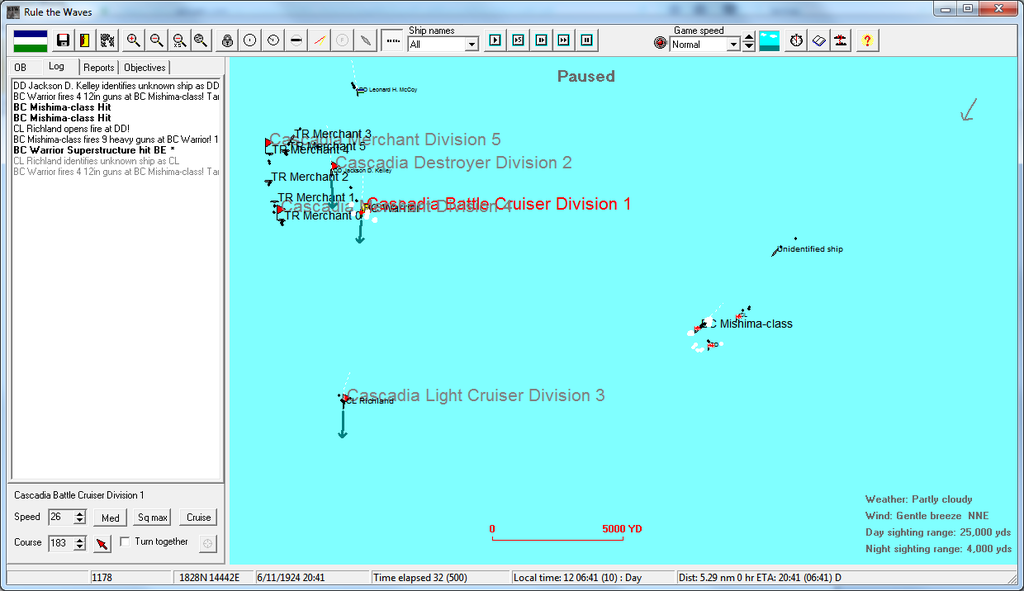

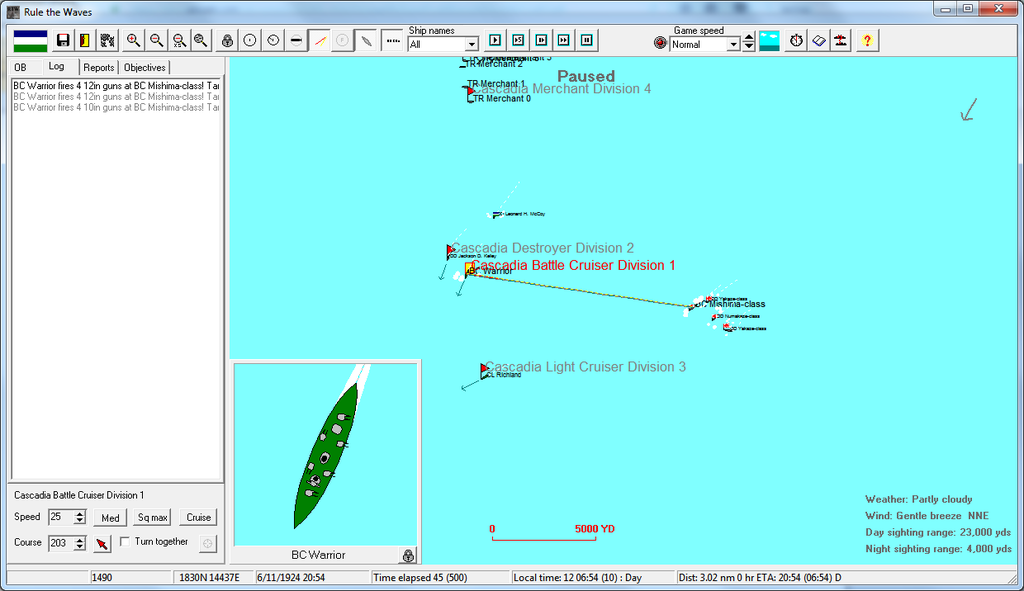

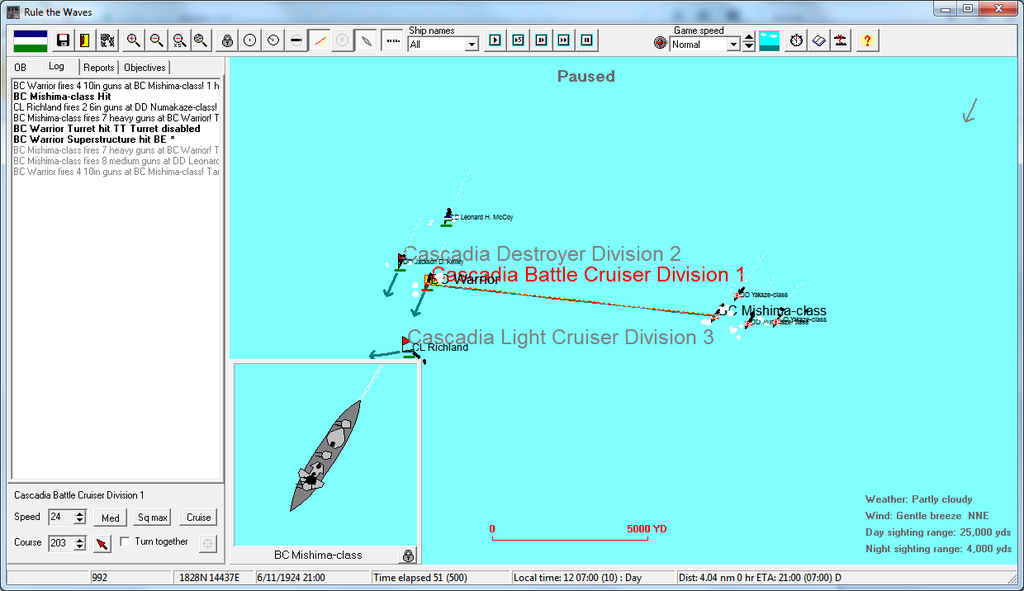

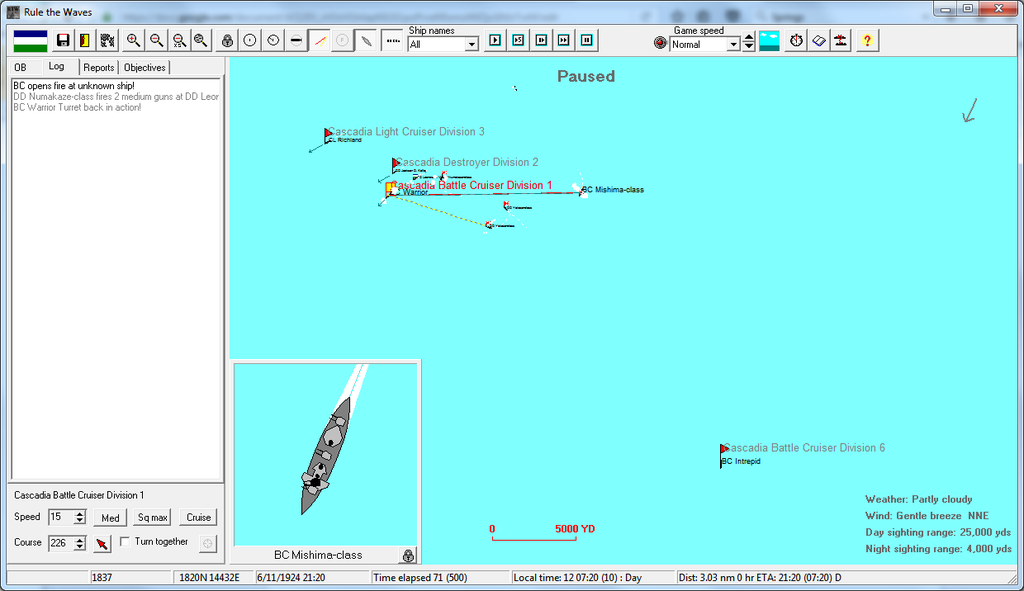

Japanese efforts to cut off Cascadia's supply lines to East Asia continued. The battlecruiser

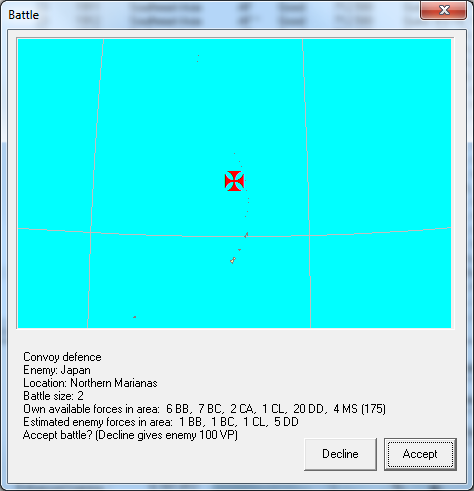

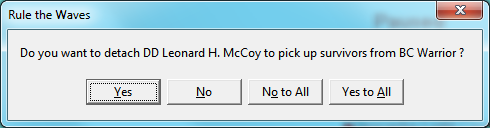

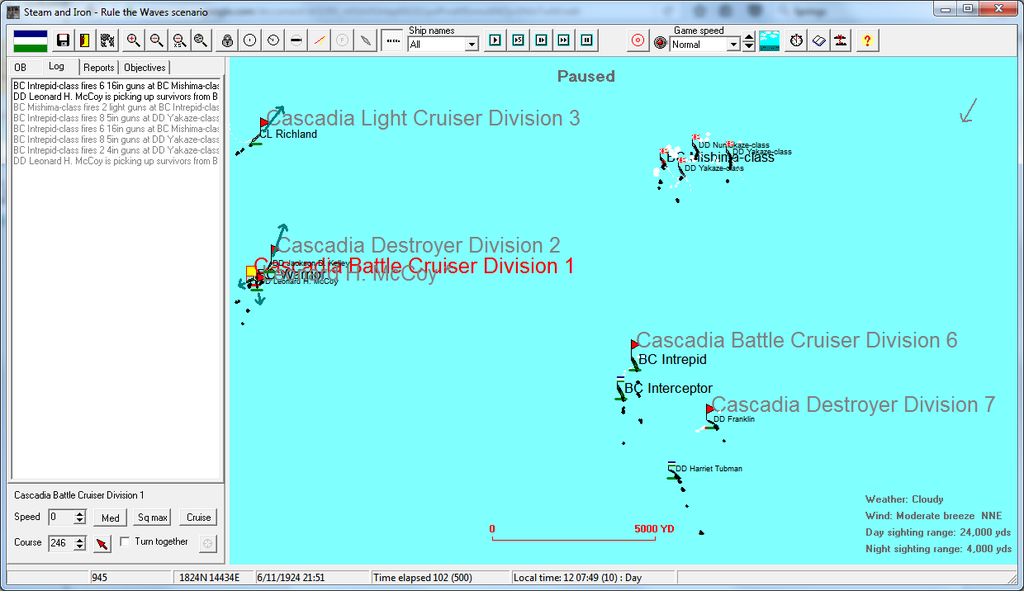

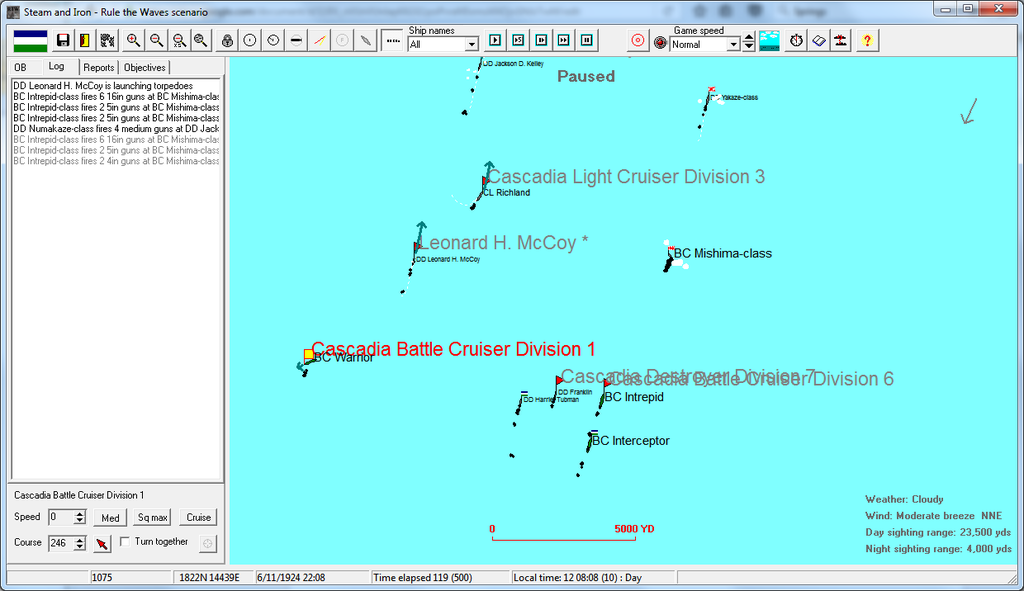

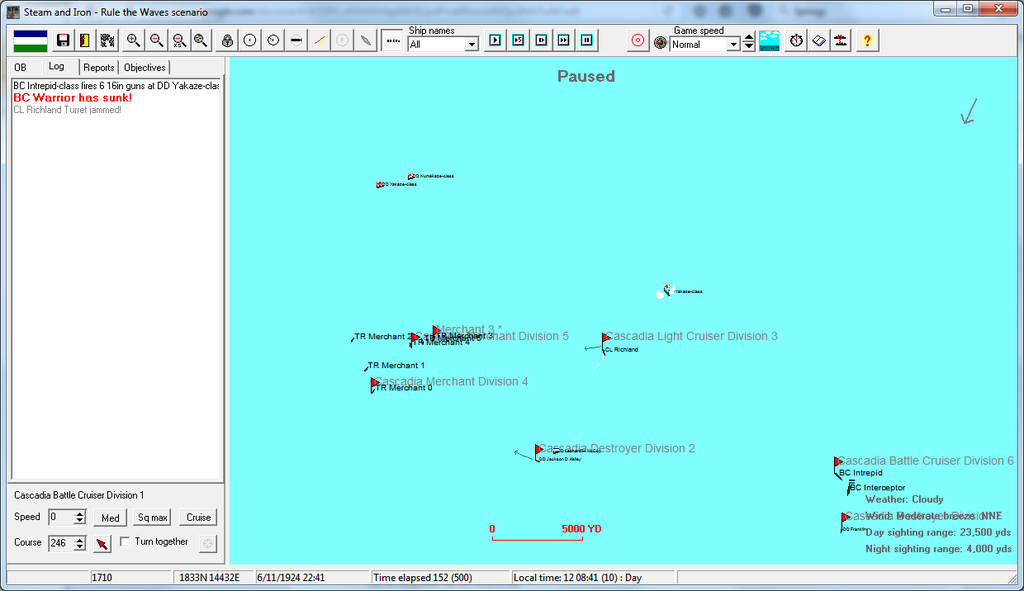

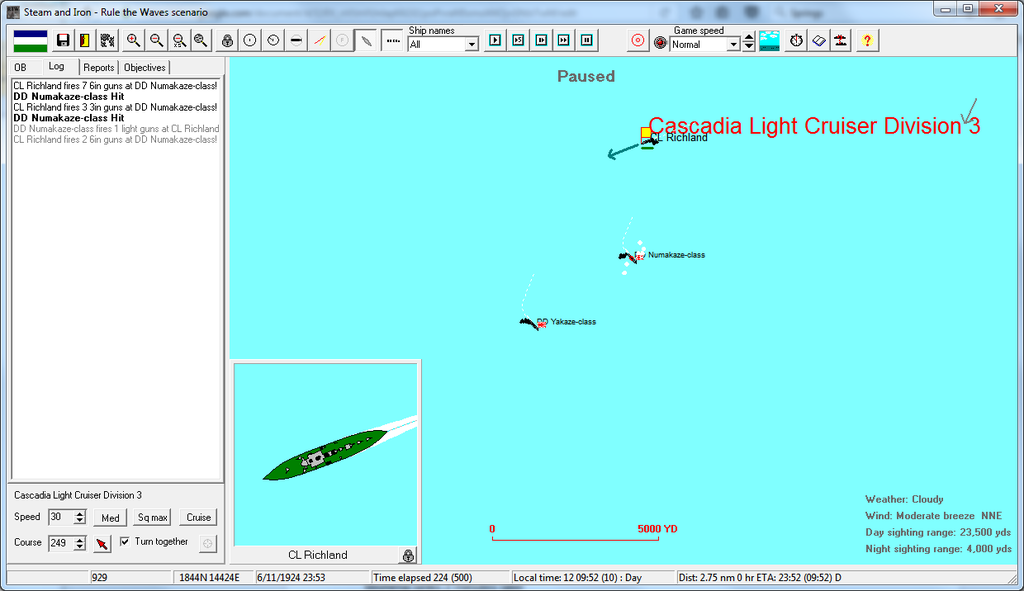

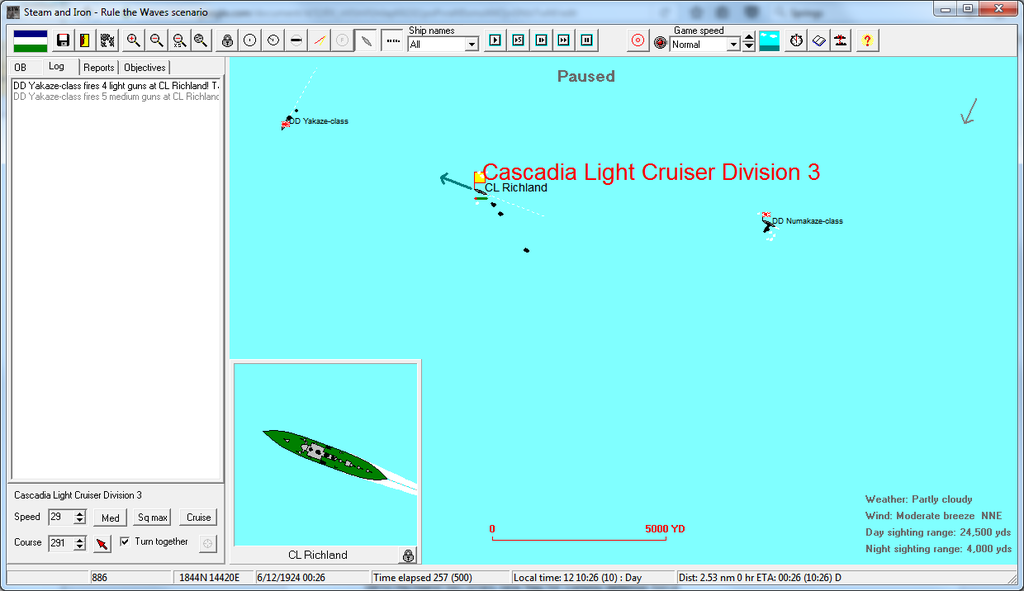

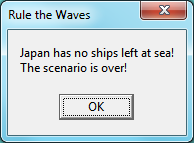

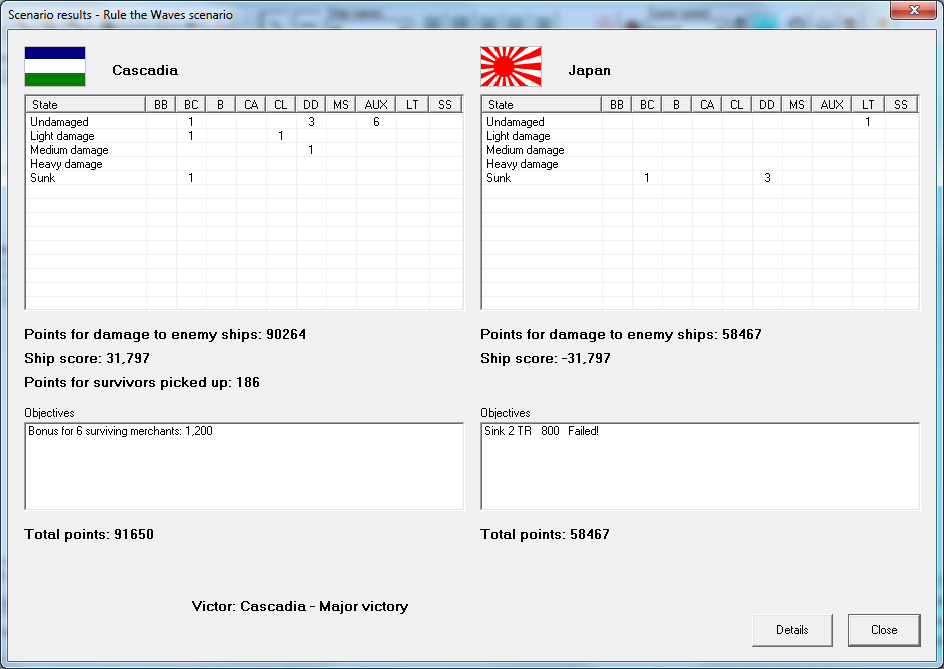

Mishima led a force of destroyers after a troop convoy at the northwest corner of the Marianas, making contact on June 11th.

Meanwhile, steaming in from the north, the venerable

Warrior, the first of the battlecruisers to sail the seas, made her way to protect the exposed convoy.